Access to Finance in Malawi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report & Financial Statements

2014 ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT BANK TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL 3 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 5 PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT 8 Strategic Overview 8 Operations 11 Project and Infrastructure Finance (PIF) 11 Trade Finance 11 Funds Management 11 Risk Management 11 Resource Mobilization 12 International Ratings 13 Financial Management 14 Human Resources and Administration 15 Conclusion 15 3 STATEMENT ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 16 SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING STATEMENT 20 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT 24 FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT & TREASURY 30 OPERATIONS 36 Project and Infrastructure Finance 38 Trade Finance 40 Funds Management 43 Portfolio Management 44 Compliance and Risk Management 45 Human Resources and Administration 47 2014 Annual Report & Financial Statements & Financial Annual Report 2014 Information Technology 48 ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 49-151 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 24% 30% LOAN ASSETS EQUITY CAPITAL US$ 2.51billion US$ 622 million 16% 31% NET PROFIT NON-PERFORMING US$ 77 million LOANS 3.04% LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL 5 The Chairman Board of Governors Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank Dear Mr. Chairman, In accordance with Article 35(2) of the Bank’s Charter, I have the honour, on behalf of the Board of Directors, to submit herewith the Annual Report of the Bank for the period 1 January to 31 December 2014. The report covers the year’s activities and audited financial statements for the period. 2014 Annual Report & Financial Statements & Financial Annual Report 2014 Mr. Chairman, please accept the assurances of my highest consideration. MR. RUPERT HORACE SIMEON Chairman of the Board of Directors 6 2014 Annual Report & Financial Statements & Financial Annual Report 2014 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT Chairman’s Statement The African and International Economic Context subscribed up to 98% of the General Capital Increase launched in 2007. -

2015 BROOKINGS FINANCIAL and DIGITAL INCLUSION PROJECT REPORT Measuring Progress on Financial Access and Usage

WASHINGTON, DC | AUGUST 26, 2015 THE 2015 BROOKINGS FINANCIAL AND DIGITAL INCLUSION PROJECT REPORT Measuring Progress on Financial Access and Usage BY JOHN D. VILLASENOR, DARRELL M. WEST, AND ROBIN J. LEWIS About the Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings The Center for Technology Innovation (CTI) at Brookings focuses on delivering research that impacts public debate and policymaking in the arena of U.S. and global technology innovation. CTI’s goals include: Identifying and analyzing key developments to increase innovation; developing and publicizing best practices to relevant stakeholders; briefing policymakers about actions needed to improve innovation; and enhancing the public and media’s understanding of technology innovation. About the Brookings Institution The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. WASHINGTON, DC | AUGUST 26, 2015 THE 2015 BROOKINGS FINANCIAL AND DIGITAL INCLUSION PROJECT REPORT Measuring Progress on Financial Access and Usage BY JOHN D. VILLASENOR, DARRELL M. WEST, AND ROBIN J. LEWIS Comments and feedback regarding the Financial and Digital Inclusion Project can be submitted to [email protected]. THE 2015 BROOKINGS FINANCIAL AND DIGITAL INCLUSION PROJECT REPORT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................ 2 THE IMPORTANCE OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION ............................... 7 MEASURING FINANCIAL INCLUSION .......................................... 10 DIMENSIONS OF EVALUATION ................................................... 12 Overall ranking on financial inclusion .................................. -

FDH Bank Financials 2019 FINAL

SUMMARY AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FDH BANK FDH Bank FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019. LIMITED Main Highlights Net interest Income 7% Total Income Non Interest income 23% 10 40 K34.3 K7.8 Billion Corporate Social Responsibility 21% Billion K29 8 Billion a a 2019 K5.9 30 ach Billion 2019 ach Total Assets 24% Kw 6 Kw 2018 2018 20 4 Loan Book Growth 40% 10 Amount in Billion 2 32% Amount in Billion 18% Increase Increase Return on Equity 35% 0 0 NPL Ratio down to 0.80% K Customer Deposits Basic Earnings per Introduced WhatsApp Banking Share (Tambala) K137.1 Billion New Branch Goliati - Thyolo 150 2000 K112.5 1,696 Tambala a Billion 2019 1,289 Tambala ach 1500 Upgraded Branches Mulanje, Chiponde, Mzimba, Kw 100 2019 and Agencies Chitipa, Jenda & Neno 2018 ambala 2018 1000 50 Amount in T 500 Amount in Billion 22% 32% Increase Increase 0 0 FDH BANK LIMITED FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR Malawi GDP growth rate is projected to average between 5% and 6%, according to the Reserve Bank of Malawi. YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019. Private sector credit annual growth in 2019 was 21.3% up from 11.5% in 2018. The The Directors present the audited summarised financial statements of FDH Bank stronger growth in private sector credit in 2019 is a reflection of reduced interest rates. Limited for the year ended 31 December 2019. We anticipate the low interest rates regime to continue and spur private sector credit growth in 2020. PERFORMANCE The Bank continues to consolidate and improve on the convenient delivery channels The Directors report a profit after tax of K7.846 billion for the year ended 31 through its digital products and providing innovative first class financial solutions. -

Financial Market Update I Week Ending 21 May 2021 Financial Market Highlights for the Week Ending 21 May 2021

Financial Market Update I Week ending 21 May 2021 Financial market highlights for the week ending 21 May 2021 The following highlights compare the week ending 21 May 2021 to the week ending 13 May 2021: Government securities market (Source: RBM) Equity market (Source: MSE) • A total of K12.73 billion was allotted during this week’s • The stock market was bullish this week as the MASI Treasury Bills (TBs) and 2-Year Treasury Note (TN) marginally increased to 33,606.87 points from 33,398.30 auctions. points in the previous week. This was due to share price • There were nil rejections during the TB auctions. gains for Airtel (to K32.50 from K31.02) and Standard bank • The 2-Year TN had a rejection rate of 13.37%. (to K1,200.15 from K1,200.14), which offset share price • The 364-days TB had the highest subscription rate of losses for MPICO (to K17.00 from K19.00), ICON (to K12.14 59.95%. from K12.16), TNM (to K16.34 from K16.35), and FDH bank (to K16.42 from K16.46), during the period under review. Currency market (Source: RBM) • The year-to-date return of the MASI was 3.75% at the close • Based on middle rates, the Malawi Kwacha marginally of this week. It was negative 5.78% in the previous year, depreciated against the USD by 0.14% to K802.22/USD from during the same period. K801.11/USD in the previous week. Financial market developments (Source: RBM & • Based on middle rates, the Kwacha also depreciated against the GBP (to K1,192.11/GBP from K1,175.77/GBP) , the EUR Company Financials) (to K1,040.81/EUR from K1,025.90/EUR) and the ZAR (to • The average overnight interbank rate maintained its position K61.19/ZAR from K60.45/ZAR), during the period under at 11.92% during the period under review. -

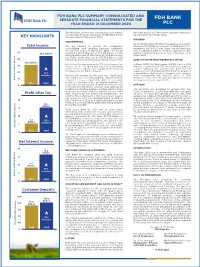

Fdh Bank Plc Summary Consolidated and Separate Financial Statements for the Fdh Bank Year Ended 31 December 2020 Plc

FDH BANK PLC SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED AND SEPARATE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FDH BANK YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 PLC The Directors present the summarized consolidated per share and as at 31 December 2020 the share price and separate financial statements of FDH Bank Plc for had moved to K14.45 per share. KEY HIGHLIGHTS the year ended 31 December 2020. DIVIDEND PERFORMANCE On 8 February 2021, the Directors approved an interim Total Income We are pleased to present the summarized dividend of K3.0 billion in respect of 2020 profits, this consolidated and separate financial statements represents 43t (K0.43) per share. The dividend was for the year ended 31 December 2020. The Group paid on 26 March 2021 to members appearing in the 50 43.6 Billion reported a profit after tax of K14.368 billion and the register of the Company as at close of business on 12 Bank reported a profit after tax of K14.956 billion from March 2021. the Bank’s profit after tax of K5.193 billion in 2019 40 (Restated) amid a challenging operating environment. ACQUISITION OF MSB PROPERTIES LIMITED 30.6 Billion Net Interest Income went up by 77% on the back of an In March 2020, the Bank acquired 100% stake in MSB 30 increase in the loan book and other interest bearing Properties Limited from FDH Money Bureau Limited, assets. Interest expense went up by 15.8% reflecting a sister company. The consideration given for the the growth of the Bank’s deposits. acquisition was K5.599 billion. The Bank has prepared 20 42% a consolidated statement of comprehensive income Increase Non-interest Income in the year was significantly which incorporates the financial results of MSB 10 affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. -

Fdh Bank Plc Ipo Pre-Listing Statement

FDH BANK PLC IPO FDH Bank PRE-LISTING STATEMENT FDH Bank Offer for Sale of 979,175,000 Ordinary Shares and Offer for Subscription of 401,031,250 Ordinary Shares each at an Offer Price of MWK10.00 per Share and admission to trade on the Malawi Stock Exchange A copy of the Pre-Listing Statement has been delivered to and registered by the Registrar of Financial Institutions (‘Registrar’). The Registrar has not checked and will not check the accuracy of any statements and they accept no responsibility therefor or for the financial soundness of FDH Bank Plc or the value of the securities offered. The Registrar registered this Pre-Listing Statement on 26th June 2020 CORPORATE ADVISORS PRE-LISTING STATEMENT Lead Corporate Advisor Legal Advisor This Pre-Listing Statement is in respect of an Offer for Sale of up Ernst & Young Tembenu, Masumbu & Company to 979,175,000 ordinary shares and Offer for Subscription of up to Chartered Accountants Malawi Gelu House 401,031,250 ordinary shares (‘Offer Shares’) each at an Offer Price of Apex House, Kidney Crescent Kamuzu Procession Rd MWK10.00 per Share and admission to trade on the Malawi Stock P.O. Box 530 P.O. Box 2777 rd Blantyre, Malawi Lilongwe, Malawi Exchange with effect from the commencement of trading on Monday, 3 Tel +265 (0) 1 876 476 Tel +265 (0) 1 756 286 August 2020 (‘the Listing Date’). [email protected] [email protected] Reporting Accountant Transfer Secretary This Pre-Listing Statement is not an invitation to the public to subscribe for shares but is issued in compliance with the rules and requirements of the Deloitte NICO Asset Managers Limited Malawi Stock Exchange for the purpose of giving information to the public Chartered Accountants Malawi Chibisa House P.O. -

August 2020 August 2020 November 2020

AUGUST 2020 AUGUST 2020 NOVEMBER 2020 1 MONTHLY ECONOMIC REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ECONOMIC OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Inflation (Source: NSO) ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Government Securities (Source: RBM) ............................................................................................................................. 6 Foreign Currency Market (Source: RBM) ......................................................................................................................... 6 Interbank Markets and Interest Rates (Source: RBM)...................................................................................................... 6 Stock Market (Source: MSE) ............................................................................................................................................. 7 OTHER MARKET DEVELOPMENTS ....................................................................................................................... 9 Tobacco Markets Update -

Fdh Bank Plc Ipo Pre-Listing Statement

FDH BANK PLC IPO FDH Bank PRE-LISTING STATEMENT FDH Bank Offer for Sale of 979,175,000 Ordinary Shares and Offer for Subscription of 401,031,250 Ordinary Shares each at an Offer Price of MWK10.00 per Share and admission to trade on the Malawi Stock Exchange A copy of the Pre-Listing Statement has been delivered to and registered by the Registrar of Financial Institutions (‘Registrar’). The Registrar has not checked and will not check the accuracy of any statements and they accept no responsibility therefor or for the financial soundness of FDH Bank Plc or the value of the securities offered. The Registrar registered this Pre-Listing Statement on 26th June 2020 CORPORATE ADVISORS PRE-LISTING STATEMENT Lead Corporate Advisor Legal Advisor This Pre-Listing Statement is in respect of an Offer for Sale of up Ernst & Young Tembenu, Masumbu & Company to 979,175,000 ordinary shares and Offer for Subscription of up to Chartered Accountants Malawi Gelu House 401,031,250 ordinary shares (‘Offer Shares’) each at an Offer Price of Apex House, Kidney Crescent Kamuzu Procession Rd MWK10.00 per Share and admission to trade on the Malawi Stock P.O. Box 530 P.O. Box 2777 rd Blantyre, Malawi Lilongwe, Malawi Exchange with effect from the commencement of trading on Monday, 3 Tel +265 (0) 1 876 476 Tel +265 (0) 1 756 286 August 2020 (‘the Listing Date’). [email protected] [email protected] Reporting Accountant Transfer Secretary This Pre-Listing Statement is not an invitation to the public to subscribe for shares but is issued in compliance with the rules and requirements of the Deloitte NICO Asset Managers Limited Malawi Stock Exchange for the purpose of giving information to the public Chartered Accountants Malawi Chibisa House P.O. -

FDH BANK 2020 Half Year Financial Statements

SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED UNAUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE HALF FDH BANK FDH Bank YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE, 2020 PLC FDH Bank FDH BANK PLC SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED UNAUDITED FINANCIAL Key Highlights RESULTS FOR THE HALF YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 The Directors present the unaudited consolidated summarized financial statements of FDH Bank Plc for 20 the half year ended 30 June 2020. K15.3 K14.4 PERFORMANCE Billion Billion The Bank registered a profit after tax of K3.223 billion against K3.351 billion profit achieved over a similar 15 JUNE period last year. Total income grew by 7% from K14.418 billion to K15.380 billion. Net-interest income JUNE 2020 went up by 65% on the back of an increase in interest income by 45% following the increase in loan 2019 book & government securities portfolio and interest expense went up by 22% as a result of an increase 10 in deposits which supported the loan book growth. Notwithstanding the growth in deposits, enhanced balance sheet management has seen the Bank’s cost of funding going down. The Bank continues to put more focus on effective cost management as we continue to bring down the Amount in Billion Kwacha 5 cost to income ratio. Operating expenses grew by 8% when compared to the same period last year. The Profit before provision for loan impairment and Tax (PBIT) was 4% above the PBIT for the same period 7% last year. However, there was an increase in Net impairment charges due to the corona virus disease of increase 0 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. -

FDH BANK PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020 FDH Bankfdh Bank Discount Discountfirst First Housediscount House First House

FDH Bank Plc Contents Company information and profile 1 Vision, Mission and Core Values 3 Financial Highlights 4 The Board of Directors 6 Executive Management 8 Board Committees Composition 10 Directors’ Reports 11 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 20 Our Year 22 Independent Auditor’s Report 29 Financial Statements 34 Statements of Financial Position 35 Statements of Comprehensive Income 36 Statements of Changes in Equity 37 Statements of Cashflows 39 Notes to the Financial Statements 41 1 Company Information Company Secretary: Registered office of the Company: Transfer Secretaries: Auditors: Mr. Juliano Godfrey FDH Bank Plc NICO Asset Managers Limited Deloitte Kanyongolo Umoyo House Chibisa House P.O. Box 512 19 Glyn Jones Road Principal Attorneys: Managing Director: Blantyre, Malawi P.O. Box 3173 Mbendera and Nkhono Dr. Ellias Ngalande Tel: +265 (0) 1 820 219 Blantyre, Malawi Associates info@ fdh.co.mw Tel: +265 (0) 1 832 085 www.fdh.co.mw [email protected] FDH Bank Plc Profile FDH Bank Plc (‘The Bank’) was incorporated and registered in Blantyre, Malawi on 16 May 2007, with registration number 8328 under the Companies Act, 1984, as repealed by the Companies Act, 2013, as a private limited liability company. The Company was re-registered as a public limited liability company under the Companies Act, 2013 on 3 June 2020. The Bank is also registered with the Reserve Bank of Malawi (‘RBM’) as a commercial bank and authorized dealer for exchange control purposes. The Bank’s registered office is situated at Umoyo House, Victoria Avenue, P.O. Box 512, Blantyre, Malawi. On 3 August 2020, the Bank was listed on the Malawi Stock Exchange. -

Annexure 2008

ANNEXURE A _______________________________________________________ SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY (SADC) PAYMENT SYSTEM PROJECT COUNTRY-SPECIFIC PROGRESS REPORTS FOR PERIOD APRIL 2008 TO MARCH 2009 ________________________________________________________________ REPORTS 1. ANGOLA 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Angolan Payment System (SPA) infrastructure encompasses a fully functional and up to standard RTGS system (SPTR); a semi automated clearing house for cheques and credit transfers (SCV); Multicaixa, an Automated teller Machine (ATM) / Point Of sale (POS) switching system; and a new Central Securities Depository (SIGMA) for dematerialized Government bills and bonds and securities issued by the BNA. In order to reach the objectives drawn in the preterit year, the Head of the Department tried in the incessant form to excel for the improvement in all the processes of work aiming at the satisfaction of the settled objectives, as well as making sure in the course of the year that the methods and proceedings adopted in the development of the activities were compatible with the specification of each task and in harmony with the general direction defined by BNA board of Directors. For the year of 2009, it is on course of implementing the following actions that will allow adapting the SPA to the Core Principles for SIPS: a) Implementation of the actions tenants to the creation of the Angolan Automatic Clearing House; b) Elaboration of a consolidated Manual containing all SPA legislation related to SPTR, MULTICAIXA, SCV and the CCAA; c) Approvation and publication of Oversight Policy documents, containing the objectives, scope and Angolan Payments Systems oversight standards; d) Elaboration of the Internal Procedures Manual for the Oversight Sector; e) Discussion and approvation of the Cooperation Memorandum between DSP and DSI; f) Discussion e approvation of the Cooperation Memorandum between BNA and CMC (Stock Exchange). -

Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development Reserve Bank of Malawi DRAFT STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN

FINANCIAL INCLUSION AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP SCALING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development Reserve Bank of Malawi Public Disclosure Authorized DRAFT STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN (SEP) Public Disclosure Authorized Lilongwe MALAWI 23 January 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AP Aggrieved Party COMSIP Community Savings and Investment Promotion BDS Business Development Services CLS Customary Land Committee DEA Department of Environmental Affairs EHSGs World Bank Group Environmental Health and Safety Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESCP Environmental and Social Commitment Plan ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMS Environmental and Social Management System ESS Environmental and Social Standard FI Financial Intermediaries FIF Financial Intermediary Financing FL: Financial Literacy FMO Entrepreneurial Development Bank FSTAP Financial Sector Technical Assistance Project GBV Gender Base Violence GDP Gross Domestic Product GIID Good International Industry Practice GRC Grievance Redress Committee GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism GRS Grievance Redress Service IFC International Finance Corporation LOC Line of Credit LTF Long-term Finance MAIIC Malawi Agriculture and Industrial Investment Corporation MCCCI Malawi Confederation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MFI Microfinance Institutions MGDS Malawi Growth and Development Strategy MoFEPD Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development MoITT Ministry of Industry,