Medieval English Theatre 27: See for Instructions on How to Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pamela King – [email protected] – University of Bristol, Bristol

King 0 Pamela King – [email protected] – www.bristol.ac.uk/medievalcentre University of Bristol, Bristol Thème/Topic Renaissance of Medieval Theatre Titre/Title The Renaissance of Medieval Theatre and the Growth of University Drama in England Résumé/Abstract The battle to be permitted to impersonate the deity on the stage in Britain is well documented, as is the role of theatrical impresarios such as William Poel, Nugent Monck and E. Martin Browne, the Religious Drama Society and the British Drama League. What has received less attention is the role of the universities in the latter part of this process, and in experimental productions of medieval plays. Oxford University Drama Society provided the test bed, but it was at Bristol, in the first department at a British University dedicated to the study of Drama in performance, that the renaissance of medieval religious drama found its first academic home under the aegis of Glynne Wickham and his colleagues. This paper will draw on many unpublished archive holdings from the Bristol University Theatre Collection. It will investigate the intersection between the movement which resulted in drama being accepted as a legitimate and autonomous university subject and the parallel campaign against the established conventions of censoring religious theatre in the United Kingdom. As well as charting this history, it will discuss the emergent understandings of the nature of medieval religious drama in the middle of the twentieth century in church, state and academy. King 1 The Renaissance of Medieval Theatre and the Growth of University Drama in England Pamela King The slim journal Theatre in Education, issue 5, number 25, for April 1951 carried three interestingly linked articles. -

V the POSTHUMOUS NARRATIVE POEMS OF

'/v$A THE POSTHUMOUS NARRATIVE POEMS OF C. S. LEWIS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Caroline L. Geer, B. A. Denton, Texas December, 1976 Geer, Caroline Lilian, The Posthumous Narrative Poems of C. S. Lewis. Master of Arts (English), December, 1976, 73 pp., bibliography, 15 titles. The purpose of this study is to introduce the three posthumous narrative poems of C. S. Lewis. Chapter One is an introduction to Lewis's life and scholarship. The second chapter is concerned with "Launceloti" in which the central theme of the story explores the effect of the Quest for the Holy Grail on King Arthur's kingdom. Chapter Three studies "The Nameless Isle," in which Celtic and Greek mythic ele- ments strongly influence both characterization and plot. The fourth chapter is an analysis of The Queen of Drum and its triangular plot structure in which the motivating impetus of the characters is the result of dreams. Chapter Five recapitulates Lewis1s perspectives of life and reviews the impact of his Christianity on the poems. The study also shows how each poem illustrates a separate aspect of the cosmic quest. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION. 1 II. "LAUNCELOT . 13 III. "THE NAMELESS ISLE" . 32 IV. THE QUEEN OF DRUM: A STORY jflFIVECANTOS ......... 50 V. CONCLUSION . * . 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 72 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nothing about a literature can be more essential than the language it uses. A language has its own personality; implies an outlook, reveals a mental activity, and has a resonance, not quite the same as those of any other. -

The Prologue from the Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer 1340?–1400

The Age of Chaucer The Prologue READING 3 Evaluate the changes from The Canterbury Tales in sound, form, figurative language, Poem by Geoffrey Chaucer Translated by Nevill Coghill and dramatic structure in poetry across literary time periods. VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-142A Meet the Author Geoffrey Chaucer 1340?–1400 did you know? Geoffrey Chaucer made an enormous important work around 1370, writing mark on the language and literature of was always a sideline; his primary career Geoffrey Chaucer . England. Writing in an age when French was in diplomacy. During Richard II’s • was captured and was widely spoken in educated circles, troubled reign (1377 to 1399), Chaucer held for ransom while Chaucer was among the first writers to was appointed a member of Parliament fighting for England in show that English could be a respectable and knight of the shire. When Richard the Hundred Years’ War. literary language. Today, his work is II was overthrown in 1399 by Henry • held various jobs, considered a cornerstone of English Bolingbroke (who became King Henry including royal literature. IV), Chaucer managed to retain his messenger, justice of the political position, as Henry was the son of peace, and forester. Befriended by Royalty Chaucer was John of Gaunt. • portrayed himself as a born sometime between 1340 and 1343, foolish character in a probably in London, in an era when Despite the turmoil of the 1380s and number of works. expanding commerce was helping to 1390s, the last two decades of Chaucer’s bring about growth in villages and cities. life saw his finest literary achievements— His family, though not noble, was well the brilliant verse romance Troilus off, and his parents were able to place and Criseyde and his masterpiece, The him in the household of the wife of Canterbury Tales, a collection of verse and Prince Lionel, a son of King Edward prose tales of many different kinds. -

The Year 1930 (254) Summary: on January 30, Jack Likely Experienced His Unbuckling on Top of a Bus Going up Headington Hill As W

The Year 1930 (254) Summary: On January 30, Jack likely experienced his unbuckling on top of a bus going up Headington Hill as well as the “zoo of lusts” insight. On February 3, Jack wrote his famous monastery letter to Owen Barfield in which he wrote about the “Spirit” becoming more personal. On February 25, Warren sailed from Shanghai on the freighter Tai-Yin, and on April 16 his ship landed in Liverpool. On May 25, Warren accepted Jack and Mrs. Moore’s invitation to make his home with them. On June 3, Warren left Little Lea for the last time. During the first six days of June, Jack became a theist. Warren returned to Bulford on May 15. On July 16, the offer of Warren, Jack, and Mrs. Moore to purchase the Kilns was accepted. On October 10-11, Warren helped Jack, Mrs. Moore, and Maureen move from Hillsboro to the Kilns. On October 12, Jack and Warren walked past Holy Trinity and agreed that this must be their church. In December, Warren began the work of editing The Lewis Papers while on leave. Jack writes his De Bono et Malo1 this year. Jack probably also writes his De Toto et Parte2 to Barfield this year. Jack probably writes the poem “Leaving For Ever the Home of One’s Youth,” since his father died on Sept. 25, 1929. Jack writes several undated letters to Barfield this year (see Collected Letters, III, 1519-1521). Don King dates the poem “You, Beneath Scraping Branches” to this year.3 King dates the poem “When the Year Dies in Preparation for the Birth,” elsewhere known as “Launcelot,” to one of the years between 1930 and 1933.4 Martin Lings writes a masque, which is performed in Oxford and sends a letter to Jack; Jack responds to that letter and masque in complimentary fashion.5 January 1930 January 1 Wednesday. -

Prime-Time Drama: Canterbury Tales for the Small Screen

Sydney Studies 28 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals, Prime-time Drama: Canterbury Tales trans. Francis Golffing (New York: Doubleday, 1956), p. 59. for the Small Screen 29 See Slavoj Zizek, Sublime Object, pp. 213-15. Reversing the commonly held view that the meaning of a complex text is immanent in an imaginary ‘original’ moment of response that has been lost through the process of interpretation, Zizek argues for the importance of the ‘interpretative tradi- MARGARET ROGERSON tion’ in establishing the ‘meaning’ in the fullness of its possibilities. 30 Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, p. 61. What Chaucer needs is intelligent popularization and 31 For a powerful anti-Freudian case, see Vernant and Vidal-Naquet, Myth and a good television adaptation.1 Tragedy in Ancient Greece, pp. 85-112. 32 See Sigmund Freud, From the History of an Infantile Neurosis, in The Stan- There have been many attempts to popularize Chaucer in modern times. In dard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, his informative study entitled Chaucer at Large, Steve Ellis has provided a Volume XVII, ed. and trans. James Strachey et al. (London: Hogarth Press, detailed account of the progress of such efforts over roughly a hundred years 1956). to the end of the twentieth century.2 But despite his claim that ‘Chaucer has 33 René Girard, Violence and the Sacred (Baltimore and London: Johns not really taken hold of the public in any sustained manner’,3 interest in rein- Hopkins University Press, 1977). venting the poet and, in particular, appropriating his most famous literary 34 A kommos is described in the Liddell and Scott Greek Lexicon as ‘a dirge undertaking, The Canterbury Tales, is so great that further important devel- or lamentation sung in turn by one of the actors and the Chorus’. -

CS Lewis and the Modern World

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of English Department of English 2009 "The tS ance of a Last Survivor": C. S. Lewis and the Modern World (Chapter One of The Rhetoric of Certitude) Gary L. Tandy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons The Rhetoric of Certitude The Rhetoric of Certitude C. S. Lewis's Nonfiction Prose GARY L. TANDY The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio ~/tJGSC~CK Lf/\R~r~\' ~ n[~C~.r r.cE EN"TTR U.Cr:.Cl:" F G>' U!·1iV[F;~ iTY riE\'.TUiG. Oil 9713~' Frontis: C. S. Lewis at his desk. To Janet, Julia, Jackson, Used by permission of The Marion E. Wade Center, and John Garrison. Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. And for Mom, who waits to greet us in Aslan's Country. © 2009 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242 All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2008030054 ISBN 978-0-87338-973-0 Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tandy, Gary L. The rhetoric of certitude : C. S. Lewis's nonfiction prose I Gary L. Tandy. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-o-87338-973-0 (hardcover: alk. paper) oo 1. Lewis, C. S. (Clive Staples), 1898-1963-Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PR6023.E926z898 2009 823'.912-dc22 2008030054 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available. 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Introduction ix 1 "The Stance of a Last Survivor": C. -

J.R.R. Tolkien and the Clerihew

Volume 21 Number 2 Article 39 Winter 10-15-1996 J.R.R. Tolkien and the Clerihew Joe R. Christopher Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Christopher, Joe R. (1996) "J.R.R. Tolkien and the Clerihew," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 39. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol21/iss2/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract The clerihew, a form of light verse, is part of Tolkien's oeuvre. This study offers (1) a brief history and an elaborate definition of the genre, (2) a discussion of the clerihews that have been written about Tolkien or his works, and (3) an analysis of the clerihews that Tolkien wrote. -

Hwyl and Hiraeth: Richard Burton and Wales

175 Hwyl And Hiraeth: Richard Burton And Wales Chris Williams I shall start with two brief quotations from Richard Burton.1 The first comes from an interview with Burton conducted by Kenneth Tynan in Rome in late 1966 and broadcast on the BBC in 1967. Tynan asked Burton whether there was ‘anything in the background of Wales, the cultural background, that has specifically influenced your acting?’ Burton replied: We had no actors. No actors, you know, for about forty years. I suddenly realised why we’d never had any actors. It was because all the actors went into the pulpit, the greatest stage in the world. It dominated a village in the chapel. You stood hovering like a great bird of prey over the people in the village; you said, ‘I will tell you what is wrong with you, and let me examine your soul’. The greatest pulpit in the world. And suddenly that particular kind of belief went out. They were no longer stars, the great preachers of my childhood. They went out, and the first man in Wales to stop being a preacher and start becoming an actor was Emlyn Williams. Tynan: Would it be true to say that the thing that drew you to the stage was rhetoric? Burton: Oh yes, unquestionably. I think we have a word in Welsh, misused I believe by you lot, called hwyl; nobody can ever translate it. But it’s a kind of longing for something, a kind of idiotic, marvellous, ridiculous longing.2 The second quotation is from a diary entry made by Burton on 7 December 1968, whilst at the Chalet Ariel, Gstaad, the Swiss home he shared with Elizabeth Taylor: I have a record on of ‘five thousand Welsh voices’ singing ‘Mae d’eisiau di bob awr’. -

The Canterbury Tales

Part 2 The Power of Faith Lydgate and the Canterbury Pilgrims Leaving Canterbury (detail), from the Troy Book and the Siege of Thebes, c. 1412–1422. Vellum. British Library, London. “And specially, from every shire’s end Of England, down to Canterbury they wend To seek the holy blissful martyr, quick To give his help to them when they were sick.” —Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales 81 British Library, London, UK/Bridgeman Art Library 00081081 U1P2-845482.inddU1P2-845482.indd 8181 66/21/06/21/06 9:16:209:16:20 AMAM BEFORE YOU READ from The Ecclesiastical History of the English People MEET THE VENERABLE BEDE bout the same time that a scop may have been singing in a hushed mead-hall about Athe heroic deeds of Beowulf, a monk named Bede was studying and writing in the equally quiet library of a monastery. Whereas the gifted scop remained forever nameless, this monk’s name became known throughout the world. A Life of Religious Study When Bede was a boy of seven, he went to study and live in a mon- astery at Wearmouth, England. About two years Writing History Fortunately for us, Bede was a later, Bede moved to a monastery in Jarrow, just a talented storyteller. His histories are far more short distance away. There he remained for the than mere chronicles of events; they present rest of his life, devoting himself to religion and meticulously researched stories of conquests, scholarly pursuits. saints, missionaries, and monasteries. To write his great works, Bede did research in the library of the monastery, sent letters all over the world, and spoke with artists and scholars from afar “It has ever been my delight to learn or who visited the monastery. -

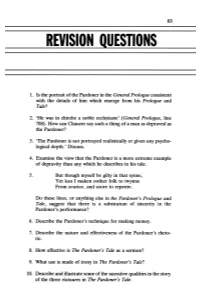

Revision Questions

83 REVISION QUESTIONS 1. Is the portrait of the Pardoner in the General Prologue consistent with the details of him which emerge from his Prologue and Tale? 2. 'He was in chirche a noble eccl~siaste' (General Prologue, line 708). How can Chaucer say such a thing of a man as depraved as the Pardoner? 3. 'The Pardoner is not portrayed realistically or given any psycho logical depth.' Discuss. 4. Examine the view that the Pardoner is a more extreme example of depravity than any which he describes in his tale. 5. But though myself be gilty in that synne, Yet kan I maken oother folk to twynne From avarice, and soore to repente. Do these lines, or anything else in the Pardoner's Prologue and Tale, suggest that there is a substratum of sincerity in the Pardoner's performance? 6. Describe the Pardoner's technique for making money. 7. Describe the nature and effectiveness of the Pardoner's rheto ric. 8. How effective is The Pardoner's Tale as a sermon? 9. What use is made of irony in The Pardoner's Tale? 10. Describe and illustrate some of the narrative qualities in the story of the three riotoures in The Pardoner's Tale. 84 11. What is the meaning and function of the old man in The Pardoner's Tale? 12. Consider some of the possible explanations of the Pardoner's offer to the pilgrims at the end of his tale. Which of these do you find the most convincing? 13. 'The Pardoner's Prologue and The Pardoner's Tale form an inseparable unit; without the one the value and impact of the other would be immeasurably decreased.' Discuss. -

The Letters of JRR Tolkien

THE LETTERS OF J. R. R. TOLKIEN A selection edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien London GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN Boston Sydney 1 To Edith Bratt...........................................................................................................................10 2 From a letter to Edith Bratt 27 November 1914.......................................................................11 3 From a letter to Edith Bratt 26 November 1915.......................................................................12 4 From a letter to Edith Bratt 2 March 1916 ...............................................................................13 5 To G. B. Smith .........................................................................................................................14 6 To Mrs E. M. Wright................................................................................................................16 7 To the Electors of the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, University of Oxford ................................................................................................................................................17 8 From a letter to the Vice Chancellor of Leeds University .......................................................19 9 To Susan Dagnall, George Allen & Unwin Ltd. ......................................................................20 10 To C. A. Furth, Allen & Unwin .............................................................................................21 11 From -

Tuber, Maarit-Hannele the Sound of English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 249 50P CS 208 601 AUTHOR Linn, Michael D.; Tuber, Maarit-Hannele TITLE The Sound of English: A Bibliography of Language Recordings. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. PUB DATE 84 NOTE 82p. AVAILABI' FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 45701, $6.50 nonmember, $5.00 member). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audiodisc Recordings; *Audiotape Recordings; Audiovisual Instruction; Authors; Diachronic Linguistics; Elementary Secondary Education; English Instruction; *Language Patterns; Music; Oral History; *Oral Language; *Regional Dialects; *Resource Materials ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers locate commercially available sound recordings that illustrate historical, regional, and nationtl varieties of English, this Looklet lists tapes and records under one of seven headings: (1) history of the English language, (2) historical periods of English, (3) American English, (4) modern non-American dialects, (5) voices of notable Americans, (6) authors reading their own works, (7) and regional music. The items under each heading are arranged in alphabetical order by title. Following the title is the name of the reader, editor or author, and producer, and--when it could be determined--the date of the recording. The format (record/cassette/reel-to-reel) and item number precedes the recording's approximate length in minutes. The suggested audience is mentioned at the end of the identification line. A list of producers and distributors immediately follows the bibliographic entries. Three indexes--a recording title index, a regional languages and dialects index, and a literature by author index--complete the booklet.