Hwyl and Hiraeth: Richard Burton and Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Tower Inspiration Page 6

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online East Tower inspiration Page 6 AUGUST 2014 • Issue 4 TV news celebrates Remembering Great (BBC) 60 years Bing Scots Page 2 Page 7 Page 8 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC TV news celebrates its 60th birthday Sixty years ago, the first ever BBC TV news bulletin was aired – wedged in between a cricket match and a Royal visit to an agriculture show. Not much has changed, has it? people’s childhoods, of people’s lives,’ lead to 24-hour news channels. she adds. But back in 1983, when round the clock How much!?! But BBC TV news did not evolve in news was still a distant dream, there were a vacuum. bigger priorities than the 2-3am slot in the One of the original Humpty toys made ‘A large part of the story was intense nation’s daily news intake. for the BBC children’s TV programme competition and innovation between the On 17 January at 6.30am, Breakfast Time Play School has sold at auction in Oxford BBC and ITV, and then with Channel 4 over became the country’s first early-morning TV for £6,250. many years,’ says Taylor. news programme. Bonhams had valued the 53cm-high The competition was evident almost ‘It was another move towards the sense toy at £1,200. immediately. The BBC, wary of its new that news is happening all the time,’ says The auction house called Humpty rival’s cutting-edge format, exhibited its Hockaday. -

Edition No.2 ANSWERS COPY Every Monday Price 3D WELCOME AND

Edition No.2 ANSWERS COPY Every Monday Price 3d WELCOME AND THANKS 3. Name the Scottish internationalist who played Thanks for all your positive feedback on Test cricket for South Africa. our first edition. KIM ELGIE 4. Jim Telfer coached Scotland’s LIVE RUGBY –WELL, ALMOST 1984 Grand Slam side and was assistant to Ian McGeechan in Great to see all the various re-runs on the 1990 but who was on the field internet and well done to Scottish Rugby in both of these Grand Slams? who were in discussion with the BBC to REFEREE FRED HOWARD show vintage matches. Scottish Rugby TV 5. Who is the most capped show matches on a Friday night. They can Scottish Ladies internationalist? be found at DONNA KENNEDY https://www.scottishrugby.org/fanzone/gri 6. Who has made the greatest d?category=scottish-rugby-tv number of international appearances without scoring a TWITTER AND FACEBOOK point? OWEN FRANKS NZ-108 CAPS As well as our own sites, there is a really 7. Which famous Scot made his good site @StuartCameronTV on Twitter. Scotland International debut Stuart recommends a vintage video from against Wales in 1953? his extensive collection. Our Facebook site BILL McLAREN is Rugby Memories Scotland Group Page 8. Who was the Scotland coach at and we are at @ClubRms on Twitter. the 1987 Rugby World Cup? DERRICK GRANT TOP TEN TEASERS 9. Which former French captain became a painter and sculptor 1. Who scored Scotland’s try in their after retiring from rugby? 9-3 win over Australia at JEAN-PIERRE RIVES Murrayfield in 1968? 10. -

Wales England

BY APPOINTMENT GIN DISTILLERS TO THE LATE KING GEORGE VI BOOTHS DISTILLERIES "...and 7 one for WALES the Home!" There is only ONE BESI ENGLAND Cardiff Arms Park SATURDAY 15th JANUARY 1955 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME ONE SHILLING ) 1 Stock WELSH RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION JOISTS yy CHANNELS ANGLES Wales TEES FLATS versus ROUNDS SQUARES England PLATES CORRUGATED CARDIFF, 15th JANUARY, 1955 SHEETS TOOLS ETC Welsh Rugby Football Union, 1954-55 PRESIDENT : W. R. Thomas, M.B.E., J.P. DUNLOP VICE-PRESIDENTS : AND T. H. Vile, J.P., Glyn Stephens, J.P., F. G. Phillips, Judge Rowe Harding, Nathan Rocyn Jones, M.A., M.D., F.R.C.S., J.P., J. E. Davies, H. S. Warrington, Hermas Evans, V. C. Phelps, W. W. Ward. RANKEN HON. TREASURER: K. M. Harris. SECRETARY: Eric Evans, M.A. LT D LEEDS When in a hurry- RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION 1954-55 TELEPHONE LEEDS 27301 PATRON: H.M. THE QUEEN (20 LINES AT YOUR SERVICE) President: W. C. RAMSAY (Middlesex) Vice-Presidents: L. CLIFFORD (Yorkshire), W. D. GIBBS (Kent) Hon. Treasurer: W. C. RAMSAY Secretary: F. D. PRENTICE Music will be provided by 1st Battalion The Welch Regiment )THE SEARCHLIGHT OF MEMORY by WILF WOOLLER FLY TO DUBLIN FOR,.. T was my good fortune to start my career for Wales at Twickenham in 1933—the first time Wales had won at the great English headquarters since their first en I counter there in 1910—a game in which England, on a day of memorable incidents, beat Wales for the first time in twelve years. In so doing, they broke through the IRELAND v. -

Beyond Soil and Blood: Curriculum As Community Building in Contexts of Profound Human Difference

BEYOND SOIL AND BLOOD: CURRICULUM AS COMMUNITY BUILDING IN CONTEXTS OF PROFOUND HUMAN DIFFERENCE By LIESA SUZANNE GRIFFIN SMITH Bachelor of Arts English Literature The University of Tulsa Tulsa, Oklahoma 1990 Master of Education School Administration Northeastern State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2019 BEYOND SOIL AND BLOOD: CURRICULUM AS COMMUNITY BUILDING IN CONTEXTS OF PROFOUND HUMAN DIFFERENCE Dissertation Approved: Dr. Hongyu Wang, Ph.D. Dissertation Adviser Dr. Tami Moore, Ph.D. Dr. Jon Smythe, Ph.D. Dr. Ed Harris, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have not traveled alone, and for that I am immensely grateful. My sister, Genyce, has told me again and again that I am writing the story that was given to me to tell, and that “what you know first stays with you” (MacLachlan, 1995, p. 20). These words have been a compass for me each time I have lost my way. And while this dissertation is about community, it is also a story that tells a good deal of who I am and who I am growing into. For this reason, it is easy for me to see that my life and my writing reflect the stamp of many whose lives are interwoven with mine. Thus, it is a great honor to recognize some of those who have cared for me, supported me, and encouraged me in my life and through the course of this writing project. I am grateful for those who first introduced me to community: my mother, Carolyn Griffin, Ed.D., and my father, Gene Griffin, J.D., who passed away prior to the completion of my dissertation. -

BD22 Neath Port Talbot Unitary Development Plan

G White, Head of Planning, The Quays, Brunel Way, Baglan Energy Park, Neath, SA11 2GG. Foreword The Unitary Development Plan has been adopted following a lengthy and com- plex preparation. Its primary aims are delivering Sustainable Development and a better quality of life. Through its strategy and policies it will guide planning decisions across the County Borough area. Councillor David Lewis Cabinet Member with responsibility for the Unitary Development Plan. CONTENTS Page 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1 Supporting Information 2 Supplementary Planning Guidance 2 Format of the Plan 3 The Community Plan and related Plans and Strategies 3 Description of the County Borough Area 5 Sustainability 6 The Regional and National Planning Context 8 2 THE VISION The Vision for Neath Port Talbot 11 The Vision for Individual Localities and Communities within 12 Neath Port Talbot Cwmgors 12 Ystalyfera 13 Pontardawe 13 Dulais Valley 14 Neath Valley 14 Neath 15 Upper Afan Valley 15 Lower Afan Valley 16 Port Talbot 16 3 THE STRATEGY Introduction 18 Settlement Strategy 18 Transport Strategy 19 Coastal Strategy 21 Rural Development Strategy 21 Welsh Language Strategy 21 Environment Strategy 21 4 OBJECTIVES The Objectives in terms of the individual Topic Chapters 23 Environment 23 Housing 24 Employment 25 Community and Social Impacts 26 Town Centres, Retail and Leisure 27 Transport 28 Recreation and Open Space 29 Infrastructure and Energy 29 Minerals 30 Waste 30 Resources 31 5 PART 1 POLICIES NUMBERS 1-29 32 6 SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL Sustainability -

Women, Health and Imprisonment Catrin

THE IMPRISONED BODY: WOMEN, HEALTH AND IMPRISONMENT CATRIN SMITH THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (SEPTEMBER 1996) DbEFNYDDIO TN er LLYFRGELL, Th U.= TO tE CqNSULTED 11BRARY UNIVERSITY OF WALES, BANGOR SCHOOL OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL PO I was never allowed to forget that being a prisoner, even my body was not my own (Maybrick, 1905 :112). The idea that law has the power to right wrongs is persuasive. Just as medicine is seen as curative rather than iatrogenic, so law is seen as extending rights rather than creating wrongs (Smart, 1989: 12) Abstract Problems affecting the female prison population have become increasingly acute. In response to a spirit of 'toughness' in penal policy, the number of women prisoners has grown sharply and more women are being sent to prison despite arguments in favour of decarceration and alternative sanctions. In prison, women make greater demands on prison health services and are generally considered to carry a greater load of physical and mental ill-health than their male counterparts. However, a gender-sensitive theory based on an understanding of the relationship between women's health and women's imprisonment has not been formulated. Health is a complex phenomenon of inseparable physical, mental and social processes. Research conducted in three women's prisons in England set out to explore the relationships between these processes. Data were generated from group discussions, in-depth interviews, a questionnaire survey and observation and participation in 'the field'. The findings suggest that women's imprisonment is disadvantageous to 'good' health. Deprivations, isolation, discreditation and the deleterious effects of excessive regulation and control all cause women to suffer as they experience imprisonment. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Past Present Future Cwmafan

About the Bevan Foundation The Bevan Foundation is Wales’ most innovative and influential think tank. We develop lasting solutions to poverty and inequality. Our vision is for Wales to be a nation where everyone has a decent standard of living, a healthy and fulfilled life, and a voice in the decisions that affect them. As an independent, registered charity, the Bevan Foundation relies on the generosity of individuals and organisations for its work, as well as charitable trusts and foundations. You can find out more about how you can support us and get involved here: https://www.bevanfoundation.org/support-us/organisations/ Acknowledgements This paper is part of the Three Towns project which is looking at the pre-conditions for growing the foundational economy in Treharris in Merthyr Tydfil, Treherbert in Rhondda Cynon Taf and Cwmafan in Neath Port Talbot. It is funded by the Welsh Government’s Foundational Economy Challenge Fund. Copyright Bevan Foundation Cover image courtesy of David Slee, Cwmafan Author – Lloyd Jones Bevan Foundation 145a High Street Merthyr Tydfil, CF47 8DP February 2021 [email protected] www.bevanfoundation.org Registered charity no 1104191 Company registered in Wales no 4175018 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

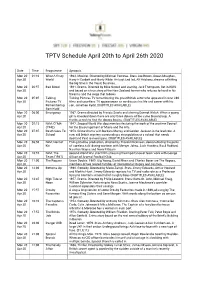

TPTV Schedule April 20Th to April 26Th 2020

TPTV Schedule April 20th to April 26th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 20 01:10 What A Crazy 1963. Musical. Directed by Michael Carreras. Stars Joe Brown, Susan Maughan, Apr 20 World Harry H Corbett and Marty Wilde. An East End lad, Alf Hitchens, dreams of hitting the big time in the music business. Mon 20 02:55 Bad Blood 1981. Drama. Directed by Mike Newell and starring Jack Thompson. Set in WW2 Apr 20 and based on a true story of the New Zealand farmer who refuses to hand in his firearms and the siege that follows. Mon 20 05:05 Talking Talking Pictures TV remembering the great British actor who appeared in over 240 Apr 20 Pictures TV films and countless TV appearances as we discuss his life and career with his Remembering son, Jonathan Kydd. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Sam Kydd Mon 20 06:00 Emergency 1962. Drama directed by Francis Searle and starring Dermot Walsh. When a young Apr 20 girl is knocked down there are only three donors of the same blood group. A frantic search to find the donors begins. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 07:15 IWM: CEMA 1942. Second World War documentary featuring the work of the wartime Council Apr 20 (1942) for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. Mon 20 07:35 Death Goes To 1953. Crime drama with Barbara Murray and Gordon Jackson in the lead role. A Apr 20 School rare, old British mystery surrounding a strangulation at a school that needs Scotland Yard to investigate. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 08:50 IWM: Next of Ealing Studios production, directed by Thorold Dickinson, demonstrating the perils Apr 20 Kin of 'careless talk' during wartime, with Mervyn Johns, Jack Hawkins, Basil Radford, Naunton Wayne and Nova Pilbeam. -

Drake Plays 1927-2021.Xls

Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls TITLE OF PLAY 1927-8 Dulcy SEASON You and I Tragedy of Nan Twelfth Night 1928-9 The Patsy SEASON The Passing of the Third Floor Back The Circle A Midsummer Night's Dream 1929-30 The Swan SEASON John Ferguson Tartuffe Emperor Jones 1930-1 He Who Gets Slapped SEASON Miss Lulu Bett The Magistrate Hedda Gabler 1931-2 The Royal Family SEASON Children of the Moon Berkeley Square Antigone 1932-3 The Perfect Alibi SEASON Death Takes a Holiday No More Frontier Arms and the Man Twelfth Night Dulcy 1933-4 Our Children SEASON The Bohemian Girl The Black Flamingo The Importance of Being Earnest Much Ado About Nothing The Three Cornered Moon 1934-5 You Never Can Tell SEASON The Patriarch Another Language The Criminal Code 1935-6 The Tavern SEASON Cradle Song Journey's End Good Hope Elizabeth the Queen 1936-7 Squaring the Circle SEASON The Joyous Season Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls Moor Born Noah Richard of Bordeaux 1937-8 Dracula SEASON Winterset Daugthers of Atreus Ladies of the Jury As You Like It 1938-9 The Bishop Misbehaves SEASON Enter Madame Spring Dance Mrs. Moonlight Caponsacchi 1939-40 Laburnam Grove SEASON The Ghost of Yankee Doodle Wuthering Heights Shadow and Substance Saint Joan 1940-1 The Return of the Vagabond SEASON Pride and Prejudice Wingless Victory Brief Music A Winter's Tale Alison's House 1941-2 Petrified Forest SEASON Journey to Jerusalem Stage Door My Heart's in the Highlands Thunder Rock 1942-3 The Eve of St. -

Pamela King – [email protected] – University of Bristol, Bristol

King 0 Pamela King – [email protected] – www.bristol.ac.uk/medievalcentre University of Bristol, Bristol Thème/Topic Renaissance of Medieval Theatre Titre/Title The Renaissance of Medieval Theatre and the Growth of University Drama in England Résumé/Abstract The battle to be permitted to impersonate the deity on the stage in Britain is well documented, as is the role of theatrical impresarios such as William Poel, Nugent Monck and E. Martin Browne, the Religious Drama Society and the British Drama League. What has received less attention is the role of the universities in the latter part of this process, and in experimental productions of medieval plays. Oxford University Drama Society provided the test bed, but it was at Bristol, in the first department at a British University dedicated to the study of Drama in performance, that the renaissance of medieval religious drama found its first academic home under the aegis of Glynne Wickham and his colleagues. This paper will draw on many unpublished archive holdings from the Bristol University Theatre Collection. It will investigate the intersection between the movement which resulted in drama being accepted as a legitimate and autonomous university subject and the parallel campaign against the established conventions of censoring religious theatre in the United Kingdom. As well as charting this history, it will discuss the emergent understandings of the nature of medieval religious drama in the middle of the twentieth century in church, state and academy. King 1 The Renaissance of Medieval Theatre and the Growth of University Drama in England Pamela King The slim journal Theatre in Education, issue 5, number 25, for April 1951 carried three interestingly linked articles.