Democracy, Rule of Law and Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point of Law. Comparative Legal Analysis of the Legal Status of Deputies of Belgium and France with Parliamentarians of the Russian Federation

Opción, Año 36, Especial No.27 (2020): 2157-2174 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 Point of Law. Comparative Legal Analysis of the Legal Status of Deputies of Belgium and France with Parliamentarians of the Russian Federation Victor Yu. Melnikov1 1Doctor of Laws. Professor of the Department of Criminal Procedure and Criminalistics Rostov Institute (branch) VGUYUA (RPA of the Ministry of Justice of Russia), Russian Federation Andrei V. Seregin2 2Associate Professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of theory and history of state and law, Southern Federal University, Russian Federation. Marina A. Cherkasova3 3Professor, Department of public administration, State University of management, Doctor of philosophy, Professor, Russian Federation Olga V. Akhrameeva4 4Associate Professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of civil law disciplines of the branch of MIREA-Russian technological University In Stavropol, Russian Federation Valeria A. Danilova5 5Associate professor, candidate of jurisprudence, Department of state and legal disciplines of the Penza state university, Russian Federation Abstract The article deals with theoretical and legal problems of constitutional guarantees of parliamentary activity on the example of Recibido: 20-12-2019 •Aceptado: 20-02-2020 2158 Victor Yu. Melnikov et al. Opción, Año 36, Especial No.27 (2020): 2157-2174 Belgium and France. The authors believe that the combination of legal guarantees with the need for legal responsibility of modern parliamentarians as representatives of the people is most harmoniously enshrined in French legislation, which is advisable to use as a model when reforming the system of people's representation of the Russian Federation. Keywords: Human rights and freedoms, Parliament, Deputies, Kingdom of Belgium, Republic of France, Constitution Punto De Ley. -

The Cracked Colonial Foundations of a Neo-Colonial Constitution

1 THE CRACKED COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS OF A NEO-COLONIAL CONSTITUTION Klearchos A. Kyriakides This working paper is based on a presentation delivered at an academic event held on 18 November 2020, organised by the School of Law of UCLan Cyprus and entitled ‘60 years on from 1960: A Symposium to mark the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus’. The contents of this working paper represent work in progress with a view to formal publication at a later date.1 A photograph of the Press and Information Office, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of Cyprus, as reproduced on the Official Twitter account of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus, 16 August 2018, https://twitter.com/cyprusmfa/status/1030018305426432000 ©️ Klearchos A. Kyriakides, Larnaca, 27 November 2020 1 This working paper reproduces or otherwise contains Crown Copyright materials and other public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0, details of which may be viewed on the website of the National Archives of the UK, Kew Gardens, Surrey, at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernment-licence/version/3/ This working paper also reproduces or otherwise contains British Parliamentary Copyright material and other Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence, details of which may be viewed on the website of the Parliament of the UK at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/ 2 Introduction This working paper has one aim. It is to advance a thesis which flows from a formidable body of evidence. At the moment when the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus (‘the 1960 Constitution’) came into force in the English language at around midnight on 16 August 1960, it stood on British colonial foundations, which were cracked and, thus, defective. -

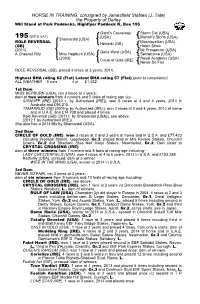

J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195 Giant's Causeway Storm Cat (USA) 195 (WITH VAT) (USA) Mariah's Storm (USA) Shamardal (USA) ROLE REVERSA L Machiavellian (USA) Helsinki (GB) (GB) Helen Street (2011) Mr Prospector (USA) Gone West (USA) A Chesnut Filly Miss Hepburn (USA) Secrettame (USA) (2003) Royal Academy (USA) Circle of Gold (IRE) Never So Fair ROLE REVERSAL (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 62 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 57 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 5 runs 4 pl £1,532 1st Dam MISS HEPBURN (USA), ran 3 times at 2 years; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SIGNOFF (IRE) (2010 c. by Authorized (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years, 2014 in Australia and £96,215. TAMARRUD (GB) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2013 at home and in U.A.E. and £14,738 and placed 4 times. Role Reversal (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), see above. (2012 f. by Authorized (IRE)). She also has a 2013 filly by Shamardal (USA). 2nd Dam CIRCLE OF GOLD (IRE) , won 3 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £77,423 including Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 , placed third in Mrs Revere Stakes, Churchill Downs, Gr.2 and Shadwell Stud Nell Gwyn Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3 ; Own sister to CRYSTAL CROSSING (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- LADY CHESTERFIELD (USA) , won 4 races at 4 to 6 years, 2013 in U.S.A. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8 5 9 5 10

NAKAYAMA SUNDAY,OCTOBER 4TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1200m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:6Dec.09 1:10.2 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Tomoyuki Nakamura 770,000 S 20002 Life40004M 20002 1 1 B 55.0 Yuichiro Nishida(0.8%,1−2−4−121,133rd) Turf40004 I 00000 Maradona(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 .Pelusa(0.05) .Kane Hekili C2,ch. Takaki Iwato(4.9%,11−20−10−183,113rd) Course00000E 00000 Wht. /Maradona Spin /Bambina Coco 23Feb.18 Bamboo Stud Wet 00000 2Aug.20 NIIGATA MDN T1200Fi 11 13 1:11.8 18th/18 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468' Nishino Adjust 1:10.1 <3/4> Tosen Gaia <1/2> Meiner Amistad 19Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1200Fi 7 6 1:11.3 4th/11 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468% Seiun Deimos 1:10.2 <2 1/2> Longing Birth <4> High Priestess 5Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1800Yi 45310 1:54.0 11th/11 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466' Cosmo Ashura 1:50.2 <NK> Magical Stage <NK> Seiun Gold 20Jun.20 TOKYO NWC T1400Go 4 4 1:24.9 7th/16 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466* Cool Cat 1:23.4 <2> Songline <1 1/4> Bisboccia Ow. Toshio Isobe 0 S 20002 Life20002M 00000 1 2 53.0 Akira Sugawara(4.5%,18−25−31−324,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 Isoei Hikari(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 .A Shin Hikari(0.54) .South Vigorous C2,b. -

Opinion on the Revision of the Constitution of Belgium

Strasbourg, 20 June 2012 CDL-AD(2012)010 Opinion No. 679 / 2012 Or. Engl. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) OPINION ON THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION OF BELGIUM adopted by the Venice Commission at its 91 st Plenary Session (Venice, 15-16 June 2012) on the basis of comments by Mr Christoph GRABENWARTER (Member, Austria) Mr Peter PACZOLAY (Member, Hungary) Ms Anne PETERS (Substitute Member, Germany) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2012)010 - 2 - I. Introduction 1. On 23 April 2012, after members of a political party belonging to the opposition brought the matter to the attention of the Council of Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe asked the Venice Commission to provide an opinion on the recent constitutional amendment procedure in Belgium, more particularly concerning the amendment to Article 195 of the Constitution relating to the revision of the Constitution. 2. Mr Christoph Grabenwarter, Mr Peter Paczolay and Ms Anne Peters were appointed as rapporteurs. 3. The present opinion was adopted by the Venice Commission at its 91 st plenary session on 15-16 June 2012. II. The amendment procedure of the Belgian Constitution 4. In the Constitution promulgated on 7 th February 1831 the constituent power created a decentralised and unitary State in Belgium. This form of State existed until 1970 when a gradual and comprehensive State reform started. 1 The present amendment of the Constitution was aimed at opening the way for the sixth stage of the State reform that should also contribute to the solution of the governmental and political crisis of the country. -

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., Ph.D. – C.V

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., PH.D. (203) 809-8500 • ZACHARY . KAUFMAN @ AYA . YALE. EDU • WEBSITE • SSRN ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS SCHOOL OF LAW (Jan. – May 2022) Visiting Associate Professor of Law UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LAW CENTER (July 2019 – present) Associate Professor of Law and Political Science (July 2019 – present) Co-Director, Criminal Justice Institute (Aug. 2021 – present) Affiliated Faculty Member: • University of Houston Law Center – Initiative on Global Law and Policy for the Americas • University of Houston Department of Political Science • University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs • University of Houston Elizabeth D. Rockwell Center on Ethics and Leadership STANFORD LAW SCHOOL (Sept. 2017 – June 2019) Lecturer in Law and Fellow EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD – D.Phil. (Ph.D.), 2012; M.Phil., 2004 – International Relations • Marshall Scholar • Doctoral Dissertation: From Nuremberg to The Hague: United States Policy on Transitional Justice o Passed “Without Revisions”: highest possible evaluation awarded o Examiners: Professors William Schabas and Yuen Foong Khong o Supervisors: Professors Jennifer Welsh (primary) and Henry Shue (secondary) o Adaptation published (under revised title) by Oxford University Press • Master’s Thesis: Explaining the United States Policy to Prosecute Rwandan Génocidaires YALE LAW SCHOOL – J.D., 2009 • Editor-in-Chief, Yale Law & Policy Review • Managing Editor, Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal • Articles Editor, Yale Journal of International Law -

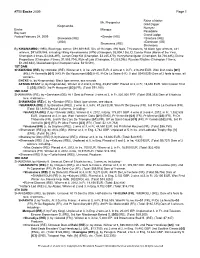

750 Encke 2009 Page 1

#750 Encke 2009 Page 1 Raise a Native Mr. Prospector Gold Digger Kingmambo Nureyev Encke Miesque Pasadoble Bay Colt Grand Lodge Foaled February 24, 2009 =Sinndar (IRE) Shawanda (IRE) =Sinntara (IRE) (2002) =Darshaan (GB) Shamawna (IRE) Shamsana By KINGMAMBO (1990), Black type winner, $91,608,945. Sire of 16 crops. 892 foals, 718 starters, 84 black type winners, 441 winners, $91,608,945, including =King Kamehameha (JPN) (Champion, $3,904,136), El Condor Pasa (Horse of the Year, Champion 3 times, $3,468,397), Lemon Drop Kid (Champion, $3,245,370), Henrythenavigator (Champion, $2,746,485), Divine Proportions (Champion 3 times, $1,553,704), Rule of Law (Champion, $1,323,096), Russian Rhythm (Champion 3 times, $1,260,634), Walzerkoenigin (Champion twice, $410,591). 1ST DAM SHAWANDA (IRE), by =Sinndar (IRE). Winner at 3, in Ire, 225,200 EUR. 4 wins at 3, in Fr, 216,450 EUR. Won Irish Oaks [G1] (IRE), Pr Vermeille [G1] (FR), Pr De Royaumont [G3] (FR), Pr De La Seine (FR). (Total: $540,029) Dam of 2 foals to race, all winners-- ENCKE (c, by Kingmambo). Black type winner, see records. GENIUS BEAST (c, by Kingmambo). Winner at 2 and 3, in Eng, 43,857 GBP. Placed at 3, in Fr, 13,650 EUR. Won Classic Trial S. [G3] (ENG). 3rd Pr Hocquart [G2] (FR). (Total: $91,160) 2ND DAM SHAMAWNA (IRE), by =Darshaan (GB). At 1 Sent to France. 2 wins at 3, in Fr, 220,000 FRF. (Total: $39,393) Dam of 6 foals to race, 4 winners-- SHAWANDA (IRE) (f, by =Sinndar (IRE)). -

FIVE DIAMONDS Barn 2 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Three Chimneys Sales, Agent Barn Hip No. 2 FIVE DIAMONDS 1 Dark Bay or Brown Mare; foaled 2006 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy............................ Weekend Surprise Flatter................................ Mr. Prospector Praise................................ Wild Applause FIVE DIAMONDS Cyane Smarten ............................ Smartaire Smart Jane........................ (1993) *Vaguely Noble Synclinal........................... Hippodamia By FLATTER (1999). Black-type-placed winner of $148,815, 3rd Washington Park H. [G2] (AP, $44,000). Sire of 4 crops of racing age, 243 foals, 178 starters, 11 black-type winners, 130 winners of 382 races and earning $8,482,994, including Tar Heel Mom ($472,192, Distaff H. [G2] (AQU, $90,000), etc.), Apart ($469,878, Super Derby [G2] (LAD, $300,000), etc.), Mad Flatter ($231,488, Spend a Buck H. [G3] (CRC, $59,520), etc.), Single Solution [G3] (4 wins, $185,039), Jack o' Lantern [G3] ($83,240). 1st dam SMART JANE, by Smarten. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $61,656. Dam of 7 registered foals, 7 of racing age, 7 to race, 5 winners, including-- FIVE DIAMONDS (f. by Flatter). Black-type winner, see record. Smart Tori (f. by Tenpins). 5 wins at 2 and 3, 2010, $109,321, 3rd Tri-State Futurity-R (CT, $7,159). 2nd dam SYNCLINAL, by *Vaguely Noble. Unraced. Half-sister to GLOBE, HOYA, Foamflower, Balance. Dam of 6 foals to race, 5 winners, including-- Taroz. Winner at 3 and 4, $26,640. Sent to Argentina. Dam of 2 winners, incl.-- TAP (f. by Mari's Book). 10 wins, 2 to 6, 172,990 pesos, in Argentina, Ocurrencia [G2], Venezuela [G2], Condesa [G3], General Lavalle [G3], Guillermo Paats [G3], Mexico [G3], General Francisco B. -

77-803 ) John Barchi, )

ORIGINAL In the Supreme Court of tfje Utiiteb States WILLIAM Go BARRYs AS CHAIRMAN OP ) THE NEW YORK STATE RACING AND ) WAGERING BOARD, ET AL,, ) ) APPELLANTS, ) ) V, ) No. 77-803 ) JOHN BARCHI, ) APPELLEE„ <X> -rt0 c5 t/> rn to I> rn ^ ;/>— o0 <— "O —.ezrn tj-'1 4> of my) O Washington, Da C, November 7, 1978 Pages 1 thru 48 Duplication or copying of this transcript by photographic, electrostatic or other facsimile means is prohibited under the order form agreement. ^Jloouer Ideportint^ do., d)nc. i! /^ejjorfero WuJ. teflon, 7). d. 546-6666 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE 'UNITED STATES *<r WILLIAM Go BARRY, AS CHAIRMAN OF: THE NEW YORK STATE RACING AND : WAGERING BOARD, ET AL„, : a Appellants, : V o No» 77-303 JOHN BARCHI, Appellee» : ------ x Washington, D„ C„ Tuesday, November 7s 1973 The above-entitled matter came on for argument at 11:53 o'clock, a0mo BEFORE: WARREN Bo BURGER, Chief Justice of the United States WILLIAM BRENNAN, Associate Justice POTTER STEWART, Associate Justice BYRON Ro ’WHITE, Associate Justice THURGOQD MARSHALL, Associate Justice HARRY A 0 BLACKMUN, Associate Justice LEWIS Fo POWELL, JR,, Associate Justice WILLIAM Ho REHNQUIST, Associate Justice JOHN PAUL STEVENS, Associate Justice APPEARANCES : ROBERT So HAMMER, ESQ,, Assistant Attorney General, State of New York, Two World Trade Center, New York, New York 10047* on behalf of the Appellants, JOSEPH A0 FARALDO, ESQ„, 125-10 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, New York 11415, on behalf of the Appellee 2 CONTENT^ ORAL ARGUMENT OP: PAGE Robert Hammer* Esq„* on behalf of the Appellants 3 In rebuttal 45 Joseph A „ Faraldo, Esq.* on behalf of the Appellees 23 3 MRo CHIEF JUSTICE BURGER: We will hear arguments next in 77-803» Barry against Barchi. -

Pasts, Presents, and a Possible Future.1 Martin Krygier the Rule of Law Is

Paper for seminar co-sponsored by Center for Study of Law & Society, and Kadish Center for Morality, Law & Public Affairs, University of California Berkeley, 2 March 2016. The Rule of Law: Pasts, Presents, and a possible Future.1 Martin Krygier The rule of law is today so totally on every aid donor’s agenda that it has become an unavoidable cliché of international organisations of every kind. More generally, praise for it has infiltrated contemporary political moralising virtually unopposed. It might not do much to quicken the pulse, but it is prescribed for a vast array of other problems. This is a relatively recent occurrence (Krygier 2014), which one would not have predicted as recently as the 1980s – I know; I didn’t. If I’d known the stocks of rule of law would soar as they have, I would have printed money, instead of mere words, to invest in it. But I had no inkling I was talking up a goldmine. This has changed so dramatically, that in virtually every introduction to the subject, the rule of law logo-cliché has come to be joined by three supplementary clichés, meta-clichés as it were, ritual observations about cliché no.1. The first is evidenced in the preceding paragraph: everyone who writes about the rule of law begins by noting its unprecedented voguishness. Second is the observation that, along with popularity has gone promiscuity. It has a huge array of suitors around the world, and it seems happy to hitch up with them all. That has in turn resulted in a third predictable adornment of every contemporary article on the subject: the rule of law now means so many different things to so many different people, it is so ‘essentially contested’ (see Waldron 2002) and likely to remain so, that it is hard to say just what this rhetorical balloon is full of, or indeed where it might float next. -

NORTH LIGHT (Ire) B, 2001

Dosage (4-4-20-5-1); DI: 1.13; CD: 0.15 NORTH LIGHT (Ire) b, 2001 height 16.1 See gray pages—Nearctic RACE AND (BLACK TYPE) RECORD Northern Dancer, 1961 Nearctic, by Nearco Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 18s, BTW, $580,647 Danzig, 1977 636 f, 147 BTW, 4.11 AEI Natalma, by Native Dancer 2 in Eng 2 1 1 0 $7,970 3s, wnr, $32,400 3 in Eng, Fr, Ire 4 2(2) 1(1) 0 $1,961,555 1,075 f, 198 BTW, 3.93 AEI Pas de Nom, 1968 Admiral's Voyage, by Crafty Admiral 4 in Eng 1 0 1(1) 0 $20,052 Danehill, b, 1986 42s, BTW, $121,741 11 f, 8 r, 4 w Petitioner, by Petition Totals 7 3(2) 3(2) 0 $1,989,577 9s, BTW, $321,064 2,410 f, 348 BTW, 3.14 AEI Won His Majesty, 1968 Ribot, by Tenerani At 2 in England 7.97 AWD 22s, BTW, $99,430 A maiden weight for age race at Goo ($6,973, 8f in Razyana, 1981 640 f, 56 BTW, 2.39 AEI Flower Bowl, by Alibhai 1:40.80). 3s, pl, $2,412 14 f, 11 r, 9 w, 5 BTW Spring Adieu, 1974 Buckpasser, by Tom Fool At 3 in England 7s, wnr, $13,757 Champion 3yo colt 12 f, 10 r, 3 w Natalma, by Native Dancer Won Vodafone Epsom Derby (G1 in Eng, $2,500,696, Blushing Groom, 1974 Red God, by Nasrullah 12f in 2:33.70, dftg.