2News Summer 05 Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

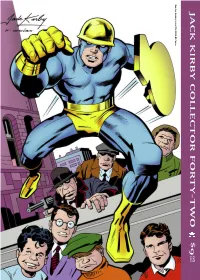

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

![[Título Do Documento] 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0720/t%C3%ADtulo-do-documento-1-220720.webp)

[Título Do Documento] 1

[Escrever o nome da empresa] 1 [Título do documento] Universidade Técnica de Lisboa Faculdade de Arquitectura Documento definitivo BATMAN: SETE DÉCADAS DE HISTÓRIA E DE ESTÓRIAS A EVOLUÇÃO DA IMAGEM DE UM HERÓI À LUZ DAS TENDÊNCIAS DA MODA Rita Daniela da Silva Camponez (Licenciada) DISSERTAÇÃO PARA OBTENÇÃO DO GRAU DE MESTRE EM DESIGN DE MODA Orientador Científico: Doutor Armando Jorge Caseirão Júri: Presidente: Doutora Manuela Cristina Figueiredo Vogais: Doutor Armando Jorge Caseirão Doutor Rui Zink - Lisboa, Dezembro de 2010 - We now say that Batman has two hundred suits hanging in “ the Batcave so they don’t have to look the same (…). Everybody loves to draw Batman, and everybody wants to put their own spin on it. (Dennis O’Neil apud Les Daniels, 1970, p. 98) “ Agradecimentos Embora esta dissertação seja, pelo seu fim académico, um trabalho de natureza individual, não seria possível a sua realização sem apoios de natureza diversa, que não podem deixar de ser realçados. Assim, gostaria de dirigir os mais verdadeiros agradecimentos a quem contribuiu, de forma directa ou indirecta, para a concretização deste projecto: À minha mãe, ao meu pai, ao Eduardo, avós e toda a família, não posso deixar de expressar e reconhecer o apoio incontestável e permanente incentivo, ânimo ou por apenas me terem dado, ao longo destes meses, o prazer da sua convivência. Ao Sérgio, meu namorado, por procurar com o seu comportamento contribuir para o meu bem-estar e felicidade, pelo estímulo e por partilhar comigo a convicção de que vale a pena um sacrifício, quando estão em causa valores e objectivos valiosos. -

Tebeografèa Kevin Maguire

TEBEOGRAFÍA KEVIN MAGUIRE Se citan, por orden de fecha de publicación, todas las obras conocidas de Kevin Maguire, cuya participación se destaca en negrita. En las ocasiones en las que Maguire sólo ha realizado una de las historias de la publicación, se menciona el título de ésta y el número de páginas. Siempre que no se haga, se supondrá que corresponde a la historia principal. Editor Serie Núm. / Título de la Portada Guión Lápiz Tinta Año historieta Marvel Hero for Hire 123 Kevin Jim Mark Jerry V- Maguire Owsley Bright Acerno 1986 Marvel Official Handbook of 6 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Joe Ru- V- the Marvel Universe binstein 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 7 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VI- the Marvel Universe Tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition Marvel Official Handbook of 8 (1 ficha) John Byrne --- Maguire Rubins VII- the Marvel Universe tein? 1986 Deluxe Edition DC Who is who in the 23 (Tattoed Man, 1 p.) Joe Staton / varios Maguire Dick I- DC Universe?: The Mike Giordano 1987 Definitive Directory DeCarlo DC Who is who in Star 1 (Elasians, 1 p.; Carol Howard Allan Maguire varios III- Trek? Marcus, 1 p.) Chaykin Asherman 1987 DC Who is who in the 25 Maguire / --- --- --- III- DC Universe?: The Dick 1987 Definitive Directory Giordano DC Who is who in Star 2 (Saavik, 1 p.) Howard Allan Maguire Joe Ru- IV- Trek? Chaykin Asherman binstein 1987 DC Justice League 1 (“Born Again”) Maguire / K. Giffen / Maguire Terry V- [Liga de la Justicia #1, Terry Austin J. M. Austin 1987 Zinco, IV-1988] DeMatteis DC Justice League 2 (“Make War No More!”) Maguire / Giffen / Maguire Al Gordon VI- [Liga de la Justicia #2, Al Gordon DeMatteis 1987 Zinco, V-1988] DC Secret Origins 15 (“Death Like a Crown”, Ed Andrew Maguire Dick VI- 15 pp.) [Universo DC Hannigan / Helfer Giordano 1987 #28, Zinco, VI-1991] Giordano DC Focus 1B (portada interior) --- --- Maguire --- VII- 1987 DC Justice League 3 (“Meltdown”) Maguire / Keith Maguire Al Gordon VII- [Liga de la Justicia #3, Al Gordon Giffen / J. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

Studies in Literature and Culture: the Graphic Novel

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators Studies in Literature and Culture: The Graphic Novel • REQUIRED TEXTS: Chynna Clugston-Major, Blue Monday: Absolute Beginners (Oni Press) Will Eisner, A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories (DC Comics) Mike Gold (Ed.), The Greatest 1950s Stories Ever Told (DC Comics) Harold Gray, Little Orphan Annie: The Sentence (Pacific Comics Club) Jason Lutes, Jar of Fools (Drawn & Quarterly) Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics (Harper-Perennial) Frank Miller and David Mazzuchelli, Batman: Year One (DC Comics) Art Spiegelman, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (Vol. I) (Pantheon) James Sturm, The Revival (Bear Bones Press) You will also need the following: • A notebook. I would like you to keep track of major points which come up in my lectures and also in our class discussions. • A folder or binder for reserve readings and class handouts. I would suggest you make copies of the reserve readings available at the library. I will also give you a number of photocopied handouts which include directed-reading questions and material which supplements the primary readings for the course. • GRADES ––Attendance and class participation (including short response papers and reading quizzes): 25% ––Writing Assignment/Mini-comic project: 25% ––Midterm exam: 25% ––Final exam: 25% * Your papers must be turned in on time! I will deduct a full grade for each day a paper is late. If you have any questions about your papers or the assigned paper topics, please see me during my office hours or by appointment. I will be glad to talk with you about our readings and about your essays. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

TARANTULA EPISODE 1.Fdx

SEESAW/MUSHROOM "TARANTULA" EPISODE 1 Written by Carson Mell EXT. TARANTULA - DAY The beautiful, decrepit Tierra Chula Resident Hotel. Early morning light. Echo exits, scratching ribs and sipping coffee, and walks right up to FRANK, a homeless guy sitting on the corner with a “Will Work For Food” sign. ECHO So, uh, that sign. You serious about that or just looking to shake loose a few crumbs from the upper crust? FRANK I’m serious. ECHO You mind if I see you erect. You know, upright. Standing up. The guy stands. He’s remarkably tall and slim, especially beside five-foot-six Echo. Echo whistles through his teeth. ECHO (CONT’D) Yep. That’ll do. EXT. TARANTULA/BACK PATIO - DAY Echo sits on Frank’s shoulders, is deep in the big avocado tree. He plucks an avocado and smells it deeply. ECHO Oh, yeah, that is the bouquet we are looking for. Echo places the avocado in his plastic grocery sack, reaches for another, and accidentally digs a knee into Frank’s side. FRANK Ah God damn! ECHO Sorry man, I know this ain’t exactly comfortable, but we gotta keep it down or my landlord is going to pop out of that window right there and shoot us with a pellet gun. Echo points up high to the window of a penthouse. 2. ECHO (CONT’D) Sir Dominic considers these avocados his sole property. Dude would charge us for each breath we took if he could. Frank looks up at the window. There’s a woman with graying hair sitting in a recliner, hooked up to oxygen. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

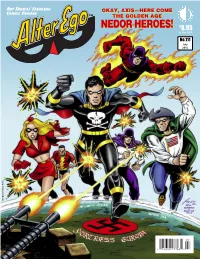

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T.