Bryoria Fremontii, Wila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Estimating Numbers of Embryonic Lethals in Conifers

Heredity 69(1992)308—314 Received 26 November 1991 OThe Genetical Society of Great Britain Estimating numbers of embryonic lethals in conifers OUTI SAVOLAINEN, KATRI KARKKAINEN & HELMI KUITTINEN* Department of Genetics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Fin/and and *Department of Genetics, University of Helsinki, He/sink,, Fin/and Conifershave recessive lethal genes that eliminate most selfed embryos during seed development. It has been estimated that Scots pine has, on average, nine recessive lethals which act during seed development. Such high numbers are not consistent with the level of outcrossing, about 0.9—0.95, which has been observed in natural populations. Correcting for environmental mortality or using partial selfings provides significantly lower estimates of lethals. A similar discordance with numbers of lethals and observed outcrossing rates is true for other species. Keywords:embryoniclethals, inbreeding depression, outcrossing, Pinus sylvestris, Picea omorika. Introduction Reproduction system of conifers Conifershave no self-incompatibility mechanisms but Theproportion of self-pollination in conifers is early-acting inbreeding depression eliminates selfed variable. Sarvas (1962) suggested an average of 26 per embryos before seed maturation (Sarvas, 1962; cent for Pinus sylvestris, while Koski (1970) estimated Hagman & Mikkola, 1963). A genetic model for this values of self-fertilization around 10 per cent. The inbreeding depression has been developed by Koski genera Pinus and Picea have polyzygotic poly- (1971) and Bramlett & Popham (1971). Koski (1971, embryony, i.e. the ovules contain several archegonia. In 1973) has estimated that Pinus sylvestris and Picea Pinus sylvestris, the most common number of arche- abies have on average nine and 10 recessive lethals, gonia is two but it can range from one to five. -

North American Fungi

North American Fungi Volume 3, Number 4, Pages 1-15 Published April 27, 2008 Formerly Pacific Northwest Fungi Changes in forage lichen biomass after insect outbreaks and fuel reduction treatments in the Blue Mountains, Oregon Bruce McCune, Sarah Jovan and Amanda Hardman Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-2902 McCune, B., S. Jovan and A. Hardman. 2008. Changes in forage lichen biomass after insect outbreaks and fuel reduction treatments in the Blue Mountains, Oregon. North American Fungi 3(4): 1-15. doi: 10.2509/naf2008.003.00a Corresponding author: Bruce McCune, [email protected]. Accepted for publication April 19, 2008. http://pnwfungi.org Copyright © 2008 Pacific Northwest Fungi Project. All rights reserved. Abstract: Forage lichens are pendulous, hairlike species eaten by a wide range of mammals. Our overall goal was to estimate losses of Bryoria, a genus of ecologically important forage species, in forests subjected to disease and fuel reduction treatments at Starkey Experimental Forest in the Blue Mountains of northeastern Oregon. Specific objectives were to (1) estimate Bryoria biomass in stands decimated by insects and disease, (2) compare Bryoria biomass in untreated stands with those treated by mechanical fuels reduction and prescribed fire, and (3) estimate the range of pre-insect outbreak Bryoria biomass using historical data. Our general approach was to estimate tree-level Bryoria biomass on a sample of trees, regress estimates against tree size and species using nonparametric multiplicative regression (NPMR), then predict stand-level biomass by applying NPMR to tree size and density data. For live trees, logarithm of dbh was a strong predictor of Bryoria biomass (cross validated R2 = xR2 = 0.83). -

Morphological Traits in Hair Lichens Affect Their Water Storage

Morphological traits in hair lichens affect their water storage Therese Olsson Student Degree Thesis in Biology 30 ECTS Master’s Level Report passed: 29 August 2014 Supervisor: Per-Anders Esseen Abstract The aim with this study was to develop a method to estimate total area of hair lichens and to compare morphological traits and water storage in them. Hair lichens are an important component of the epiphytic flora in boreal forests. Their growth is primarily regulated by available water, and light when hydrated. Lichens have no active mechanism to regulate their 2 water content and their water holding capacity (WHC, mg H2O/cm ) is thus an important factor for how long they remain wet and metabolically active. In this study, the water uptake and loss in five hair lichens (Alectoria sarmentosa, three Bryoria spp. and Usnea dasypoga) were compared. Their area were estimated by combining photography, scanning and a computer programme that estimates the area of objects. Total area overlap of individual branches was calculated for each species, to estimate total area of the lichen. WHC and specific thallus mass (STM) (mg DM/cm2) of the lichens were calculated. Bryoria spp. had a significantly lower STM compared to U. dasypoga and A. sarmentosa, due to its thinner branches and higher branch density. Bryoria also had a lower WHC compared to A. sarmentosa, promoting a rapid uptake and loss of water. All species had a significant relationship between STM and WHC, above a 1:1 line for all species except U. dasypoga. The lower relationship in U. dasypoga is explained by its less developed branching in combination with its thick branches. -

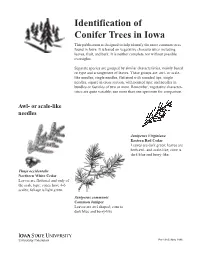

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Lichen Functional Trait Variation Along an East-West Climatic Gradient in Oregon and Among Habitats in Katmai National Park, Alaska

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Kaleigh Spickerman for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on June 11, 2015 Title: Lichen Functional Trait Variation Along an East-West Climatic Gradient in Oregon and Among Habitats in Katmai National Park, Alaska Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Bruce McCune Functional traits of vascular plants have been an important component of ecological studies for a number of years; however, in more recent times vascular plant ecologists have begun to formalize a set of key traits and universal system of trait measurement. Many recent studies hypothesize global generality of trait patterns, which would allow for comparison among ecosystems and biomes and provide a foundation for general rules and theories, the so-called “Holy Grail” of ecology. However, the majority of these studies focus on functional trait patterns of vascular plants, with a minority examining the patterns of cryptograms such as lichens. Lichens are an important component of many ecosystems due to their contributions to biodiversity and their key ecosystem services, such as contributions to mineral and hydrological cycles and ecosystem food webs. Lichens are also of special interest because of their reliance on atmospheric deposition for nutrients and water, which makes them particularly sensitive to air pollution. Therefore, they are often used as bioindicators of air pollution, climate change, and general ecosystem health. This thesis examines the functional trait patterns of lichens in two contrasting regions with fundamentally different kinds of data. To better understand the patterns of lichen functional traits, we examined reproductive, morphological, and chemical trait variation along precipitation and temperature gradients in Oregon. -

Lichens of Alaska's South Coast

United States Department of Agriculture Lichens of Alaska’s South Coast Forest Service R10-RG-190 Alaska Region Reprint April 2014 WHAT IS A LICHEN? Lichens are specialized fungi that “farm” algae as a food source. Unlike molds, mildews, and mushrooms that parasitize or scavenge food from other organisms, the fungus of a lichen cultivates tiny algae and / or blue-green bacteria (called cyanobacteria) within the fabric of interwoven fungal threads that form the body of the lichen (or thallus). The algae and cyanobacteria produce food for themselves and for the fungus by converting carbon dioxide and water into sugars using the sun’s energy (photosynthesis). Thus, a lichen is a combination of two or sometimes three organisms living together. Perhaps the most important contribution of the fungus is to provide a protective habitat for the algae or cyanobacteria. The green or blue-green photosynthetic layer is often visible between two white fungal layers if a piece of lichen thallus is torn off. Most lichen-forming fungi cannot exist without the photosynthetic partner because they have become dependent on them for survival. But in all cases, a fungus looks quite different in the lichenized form compared to its free-living form. HOW DO LICHENS REPRODUCE? Lichens sexually reproduce with fruiting bodies of various shapes and colors that can often look like miniature mushrooms. These are called apothecia (Fig. 1) and contain spores that germinate and Figure 1. Apothecia, fruiting grow into the fungus. Each bodies fungus must find the right photosynthetic partner in order to become a lichen. Lichens reproduce asexually in several ways. -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details. -

Apparent Hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F

Apparent hybridisation of Firecrest and Goldcrest F. K. Cobb From 20th to 29th June 1974, a male Firecrest Regulus ignicapillus was seen regularly, singing strongly but evidently without a mate, in a wood in east Suffolk. The area had not been visited for some time before 20th June, so that it is not known how long he had been present. The wood covers some 10 ha and is mainly deciduous, com prised of oaks Quercus robur, sycamores Acer pseudoplatanus, and silver birches Betula pendula; there is also, however, a scatter of European larches Larix decidua and Scots pines Pinus sylvestris, with an occasional Norway spruce Picea abies. Apart from the silver birches, most are mature trees. The Firecrest sang usually from any one of about a dozen Scots pines scattered over half to three-quarters of a hectare. There was also a single Norway spruce some 18-20 metres high in this area, which was sometimes used as a song post, but the bird showed no preference for it over the Scots pines. He fed mainly in the surround ing deciduous trees, but was never heard to sing from them. The possibility of an incubating female was considered, but, as the male showed no preference for any particular tree, this was thought unlikely. Then, on 30th June, G. J. Jobson saw the Firecrest with another Regulus in the Norway spruce and, later that day, D. J. Pearson and J. G. Rolfe watched this second bird carrying a feather in the same tree. No one obtained good views of it, but, not unnaturally, all assumed that it was a female Firecrest. -

Taxonomy of Bryoria Section Implexae (Parmeliaceae, Lecanoromycetes) in North America and Europe, Based on Chemical, Morphological and Molecular Data

Ann. Bot. Fennici 51: 345–371 ISSN 0003-3847 (print) ISSN 1797-2442 (online) Helsinki 22 September 2014 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2014 Taxonomy of Bryoria section Implexae (Parmeliaceae, Lecanoromycetes) in North America and Europe, based on chemical, morphological and molecular data Saara Velmala1,*, Leena Myllys1, Trevor Goward2, Håkon Holien3 & Pekka Halonen4 1) Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland (*corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected]) 2) UBC Herbarium, Beaty Museum, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada (mailing address: Enlichened Consulting Ltd., 5369 Clearwater Valley Road, Upper Clearwater, BC V0E 1N1, Canada) 3) Nord-Trøndelag University College, Serviceboks 2501, N-7729 Steinkjer, Norway 4) Botanical Museum, Department of Biology, P.O. Box 3000, FI-90014 University of Oulu, Finland Received 31 Jan. 2014, final version received 13 June 2014, accepted 18 June 2014 Velmala, S., Myllys, L., Goward, T., Holien, H. & Halonen, P. 2014: Taxonomy of Bryoria section Implexae (Parmeliaceae, Lecanoromycetes) in North America and Europe, based on chemical, morphological and molecular data. — Ann. Bot. Fennici 51: 345–371. Ninety-seven ingroup specimens of Bryoria section Implexae (Parmeliaceae, Leca- noromycetes) were studied using molecular, chemical, morphological and geographic characters. The molecular data included nuclear ribosomal markers (ITS, IGS) and the partial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene. In addition to par- simony analyses, a haplotype network was constructed. Phylogenetic analyses strongly supported the monophyly of the section Implexae. The specimens were grouped into two monophyletic clades. Clade 1 encompassed all esorediate material from North America, whereas Clade 2 included both sorediate North American material and all European material. -

Tremella Macrobasidiata and Tremella Variae Have Abundant and Widespread Yeast Stages in Lecanora Lichens

Environmental Microbiology (2021) 00(00), 00–00 doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15455 Tremella macrobasidiata and Tremella variae have abundant and widespread yeast stages in Lecanora lichens Veera Tuovinen ,1,2* Ana Maria Millanes,3 3 1 2 Sandra Freire-Rallo, Anna Rosling and Mats Wedin Introduction 1Department of Ecology and Genetics, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Norbyvägen 18D, 752 36, Sweden. The era of molecular studies has shown that most of the 2Department of Botany, Swedish Museum of Natural diversity of life is microbial (Pace, 1997; Castelle and History, Stockholm, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05, Banfield, 2018). Lichens, symbiotic consortia formed by Sweden. at least two different microorganisms, are a great mani- 3Departamento de Biología y Geología, Física y Química festation of microbial diversity in a unique package; sev- Inorgánica, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Móstoles, eral studies in the last decade have continued to E-28933, Spain. demonstrate the since long recognized presence of diverse fungal communities within lichen thalli (U’Ren et al., 2010, 2012; Fleischhacker et al., 2015; Grube and Summary Wedin, 2016; Noh et al., 2020). In recent years, attention Dimorphism is a widespread feature of tremellalean has been drawn especially to the presence of previously fungi in general, but a little-studied aspect of the biol- undetected basidiomycete yeasts in different ogy of lichen-associated Tremella. We show that macrolichens (Spribille et al., 2016; Cernajovᡠand Tremella macrobasidiata and Tremella variae have an Škaloud, 2019, 2020; Tuovinen et al., 2019; Mark abundant and widespread yeast stage in their life et al., 2020). However, little is still known about the ubiq- cycles that occurs in Lecanora lichens.