Ellen Dawson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. to Social Progress the U

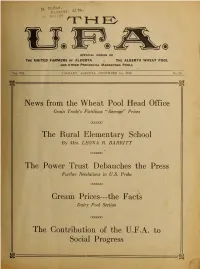

Federal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA The ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, NOVEMBER 1st,, 1928 No. 25 News from the Wheat Pool Head Office Grain Trade's Fictitious ''Average' Prices The Rural Elementary School By Mrs. LEONA R. BARRITT The Power Trust Debauches the Press Further Revelations in U.S. Probe Cream Prices- --the Facts Dairy Pool Section The Contribution of the U.F.A. to Social Progress THE U. F. A. November 1st, 1036 $7,600.00CashPrizes/ WILL BE GIVEN AWAY BY The Nor*- West Farmer In Simple Fascinating Compttition FOR YOU! m-Can You Find The" Twins''?^ FIndrhvmt Survyvucaa* They •tM*ok attkc. y«u M^f WImm* NoiBoftitil They arc not sU dttfliftJ the turn* Many young ladU* look alik* and (hv rlghirvn on ihta p*f l*ok like evcli other, but the "TWINS" are dretaed eiarily the aame. like all real rwina Now look •O'n sbowc the hart? TriaunM^ U difTereni. Un't tt> Thaf'a Hh«rc the fun mme« In. ftndlng the Twlna It take* real care and cleverncaa to point out Che diflercnce ai»d ftii4 cIm twm f««l ''t'TNS,*' baOMM tw« and oal|' iwo ar« ManticaUy Uio aame. ' ' CLUES ' ' Ar flfsc ftlanca, all tba yomm* ladle* look alike •ut YOU ARE ASK.eD TO ftSB THE "TWINS" THAT ARE (XOTHtl) F.XACTl Y ALIKE. Now then, upon clo**r e&annlnatioH, you wlU Umd a 4iffcraace In their wearing apparel. Have ihey all earring* or necklace* t How about their Kata f Arc lhay trkcuned the aame ? Some ha«e band* on the brim aad crowaa; ethara kava Mt. -

Reviews / Comptes Rendus

REVIEWS / COMPTES RENDUS John Clarke, The Ordinary People needs, which reflected their interest in of Essex: Environment, Culture, and continuity and stability even as they built Economy on the Frontier of Upper new homes in a sometimes strange coun- Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill- try. Bound by religious and ethnic ties, Queen’s University Press 2010) they attempted to cluster together and, if there were a critical mass of popula- The Ordinary People of Essex is an tion (as there was for French and English exhaustive study of the ways in which Canadians, Americans, and Germans), people shaped the land and the land married within their own ethnic and re- shaped settlement in Essex County from ligious groups. As Clarke points out, the the early to the mid-19th century. Author best land was not always the most pro- John Clarke, Distinguished Research ductive land. Settlers preferred land in Professor of historical geography at proximity to settlements, kin, or those Carleton University, has written a suc- who shared cultural or ethnic roots to cessful follow-up to his Land, Power, provide maximum support for their fam- and Economics on the Frontier of Upper ilies. Most settlers found that land was Canada (2002). With 738 pages, includ- affordable and obtained a patent in ap- ing 470 pages of text, 141 pages of notes, proximately eight years. dozens of tables and maps, and 34 pages The role of origins (defined broadly of appendices, The Ordinary People of as ethnic, social, and distinct cultural Essex represents the scholarly mastery group) is central to the book. -

Inquest Into the Death of Kerri Anne Pike, Peter Michael Dawson and Tobias John Turner

CORONERS COURT OF QUEENSLAND FINDINGS OF INQUEST CITATION: Inquest into the death of Kerri Anne Pike, Peter Michael Dawson and Tobias John Turner TITLE OF COURT: Coroners Court of Queensland JURISDICTION: CAIRNS FILE NO(s): 2017/4584, 2017/4582 & 2017/4583 DELIVERED ON: 30 August 2019 DELIVERED AT: Cairns HEARING DATE(s): 6 August 2018, 26-30 November 2018 FINDINGS OF: Nerida Wilson, Northern Coroner CATCHWORDS: Coroners: inquest, skydiving multiple fatality; Australian Parachute Federation; Commonwealth Aviation Safety Authority; Skydive Australia; Skydive Cairns; solo sports jump; tandem; relative work; back to earth orientation; premature deployment of main chute; container incompatibility with pack volume; reserve chute; automatic activation device (AAD); consent for relative work; regulations; safety management system; drop zone; standardised checking of sports equipment; recommendation for sports jumpers to provide certification for new or altered sports rigs including compatibility of main chute to container; recommendation to introduce 6 month checks by DZSO or Chief Instructor for sports rigs at drop zones to ensure compatibility. REPRESENTATION: Counsel Assisting: Ms Melinda Zerner i/b Ms Melia Benn Family of Kerri Pike: Ms Rachelle Logan i/b Ms Klaire Coles, Caxton Legal Centre Inc Family of Tobias Turner: Dr John Turner and Mrs Dianne Turner Skydive Cairns: Mr Ralph Devlin QC and Mr Robert Laidley i/b Ms Laura Wilke, Moray and Agnew Lawyers Civil Aviation Safety Mr Anthony Carter, Special Counsel Authority: Australian Parachuting -

225 Chapter Seven

225 Chapter Seven – Gastonia Ellen was the first woman organizer to arrive in Gastonia. As a result, she played a pivotal role in what is perhaps the most infamous strike in the history of the southern textile industry – the 1929 strike at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, North Carolina. Sent to Gastonia by Albert Weisbord in response to Fred Beal’s request for assistance, she arrived just days before the strike began. On March 30, 1929, at the union’s first public meeting in Gastonia, Ellen was the first speaker to address workers in a rally near the Loray Mill. In the following weeks, she was instrumental in organizing and leading the workers of Loray, men and women alike. Despite the subsequent involvement of other women activists in the Gastonia strike, women who represented a variety of organizations, Ellen had two unique characteristics that distinguished her from her female colleagues. She was the only woman organizer who was an experienced textile worker. In fact, at age 28, she had already spent half her life working in textile mills. In addition, her Scottish birth and accent provided a unique bond with southern textile workers, a majority of whom were of Scottish descent. The textile industry in the South dates to the early nineteenth century. Although there is disagreement on the exact date and location, it appears that one of the first textile mills in the Southeastern United States was constructed on the South Fork River, less than fifteen miles north of Gastonia, around 1820. The first mill in 226 Gastonia was constructed during the early 1850s. -

The Salience of Race Versus Socioeconomic Status Among African American Voters

the salience of race versus socioeconomic status among african american voters theresa kennedy, princeton university (2014) INTRODUCTION as majority black and middle class; and Orange, New ichael Dawson’s Behind the Mule, published Jersey as majority black and lower class.7 I analyzed in 1994, examines the group dynamics and the results of the 2008 presidential election in each identity of African Americans in politics.1 of the four townships, and found that both majority MDawson gives blacks a collective consciousness rooted black towns supported Obama at rates of over 90 per- in a history of slavery and subsequent economic and cent.8 The majority white towns still supported Obama social subjugation, and further argues that African at high rates, but not as high as in the majority black Americans function as a unit because of their unique towns.9 I was not surprised by these results, as they shared past.2 Dawson uses data from the 1988 National were in line with what Dawson had predicted about Black Election Panel Survey to analyze linked fate— black group politics.10 However, I was unable to find the belief that what happens to others in a person’s more precise data than that found at the precinct level, racial group affects them as individual members of the so my results could not be specified to particular in- racial group—and group consciousness among blacks dividuals.11 in the political sphere, and then examines the effects The ecological inference problem piqued my in- of black group identity on voter choice and political terest in obtaining individual data to apply my find- leanings. -

The Double Bind: the Politics of Racial & Class Inequalities in the Americas

THE DOUBLE BIND: THE POLITICS OF RACIAL & CLASS INEQUALITIES IN THE AMERICAS Report of the Task Force on Racial and Social Class Inequalities in the Americas Edited by Juliet Hooker and Alvin B. Tillery, Jr. September 2016 American Political Science Association Washington, DC Full report available online at http://www.apsanet.org/inequalities Cover Design: Steven M. Eson Interior Layout: Drew Meadows Copyright ©2016 by the American Political Science Association 1527 New Hampshire Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-878147-41-7 (Executive Summary) ISBN 978-1-878147-42-4 (Full Report) Task Force Members Rodney E. Hero, University of California, Berkeley Juliet Hooker, University of Texas, Austin Alvin B. Tillery, Jr., Northwestern University Melina Altamirano, Duke University Keith Banting, Queen’s University Michael C. Dawson, University of Chicago Megan Ming Francis, University of Washington Paul Frymer, Princeton University Zoltan L. Hajnal, University of California, San Diego Mala Htun, University of New Mexico Vincent Hutchings, University of Michigan Michael Jones-Correa, University of Pennsylvania Jane Junn, University of Southern California Taeku Lee, University of California, Berkeley Mara Loveman, University of California, Berkeley Raúl Madrid, University of Texas at Austin Tianna S. Paschel, University of California, Berkeley Paul Pierson, University of California, Berkeley Joe Soss, University of Minnesota Debra Thompson, Northwestern University Guillermo Trejo, University of Notre Dame Jessica L. Trounstine, University of California, Merced Sophia Jordán Wallace, University of Washington Dorian Warren, Roosevelt Institute Vesla Weaver, Yale University Table of Contents Executive Summary The Double Bind: The Politics of Racial and Class Inequalities in the Americas . -

The Myths That Make Us: an Examination of Canadian National Identity

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-29-2019 1:00 PM The Myths That Make Us: An Examination of Canadian National Identity Shannon Lodoen The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Plug, Jan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Gardiner, Michael The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Shannon Lodoen 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Rhetoric Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Lodoen, Shannon, "The Myths That Make Us: An Examination of Canadian National Identity" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6408. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6408 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis uses Barthes’ Mythologies as a framework to examine the ways in which the Canadian nation has been mythologized, exploring how this mythologization affects our sense of national identity. Because, as Barthes says, the ultimate goal of myth is to transform history into nature, it is necessary to delve into Canada’s past in order to understand when, why, and how it has become the nation it is today. This will involve tracing some key aspects of Canadian history, society, and pop culture from Canada’s earliest days to current times to uncover the “true origins” of the naturalized, taken-for-granted elements of our identity. -

1 in the United States District Court for the Southern

Case 1:11-cv-00110-CG-M Document 54 Filed 09/13/12 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION MICHAEL DAWSON, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) CIVIL NO. 11-0010-CG-M v. ) ) KATINA R. QUAITES, ) ) Defendant MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER ON SUMMARY JUDGMENT This matter is before the court on the unopposed motion for summary judgment filed by the plaintiff, Michael Dawson (“Dawson”). (Doc. 50). Dawson seeks summary judgment on his state law claims for assault and battery, outrage, and negligence against the defendant, Katina Quaites (“Quaites”). For the reasons stated below, Dawson’s motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. FACTUAL BACKGROUND Because Dawson’s motion is unopposed, the court adopts the undisputed facts described in the motion and accompanying affidavit. (Doc. 50 and Doc. 50-1). Dawson is employed as a police officer for the City of Daphne, Alabama. (Doc. 50-1 at 1). Like many Daphne police officers, Dawson frequently “moonlights” as a security guard when he is off-duty. Id. On the evening of May 27, 2009, Dawson was working as a security guard at 1 Case 1:11-cv-00110-CG-M Document 54 Filed 09/13/12 Page 2 of 8 Dillard’s Department Store in the Eastern Shore Center in Spanish Fort, Alabama, when store employees reported to him that they saw Quaites behaving unusually, and suspected her of stealing a dress. Id. at 2. Specifically, the employees saw Quaites take two dresses off of a clothing rack and go into the women’s changing room. -

V.2 Presentations and Announcements

The International Newsletter of Communist Studies Online XVI (2010), no. 23 152 V.2 Presentations and Announcements. Vadim V. Damier: Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20th Century. Translated from Russian by Malcolm Archibald, Edmonton, Black Cat Press, 2009. VI, 233 p. ISBN 978-0-9737827-6-9. From the preface: Anarcho-syndicalism is a fundamental tendency in the global workers’ movement. It is made up of revolutionary unions of workers (“syndicat” in French means “trade union”), acting to bring about a stateless (anarchist), self-managed society. Anarcho-syndicalism, the only mass variant of the anarchist movement in history, arose and acquired strength during a period of profound social, economic, and political changes – the first decades of the 20th century. […] It is impossible to regard anarcho-syndicalism as some kind of insignificant, marginal phenomenon – as the extravagant escapades of “extremist grouplets” or the fantasies of salon intellectuals. This is a global movement which spread to countries as different as Spain and Russia, France and Japan, Argentina and Sweden, Italy and China, Portugal and Germany. It possesses strong, healthy social roots and traditions, and was able to attract hundreds of thousands, indeed millions, of wage workers. Anarcho-syndicalists not only took an active part in the most important social upheavals and conflicts of the 20th century, often leaving their own indelible imprint on these events, but also in many countries they formed the centre of a special, inimitable, working class culture with its own values, norms, customs, and symbols. The ideas and traditions of anarcho-syndicalism, and the slogans it put forth about workplace and territorial self-management, exerted an influence on many other social movements, including the workers’ councils of Budapest (1956), the student and youth uprisings of 1968, Polish “Solidarity” in 1980-81, the Argentine “popular assemblies,” etc. -

Trotsky on Stalin and Blumkin

Vol. I l l , No. 9, Telephone: DRYdock 1656 NEW YORK, N. Y. Saturday, March"T" 1930 i— p r ic e 5 CENTS The Murder of Blumkin is An Act Build A Broad Movement Against the Russian Revolution To Aid The Unemployed The coll-b'ooded and cynically cal tion has been proved correct on every ma culates murder of the Bolshevik, Blumkin, jor issue before the C. P. S. U. and the Tlirough out the United States millions demand- for compensation, for wages must by Stalin for his adherence to the ideals of Communist International. What cynicism, of unemployed workers, their ranks in be made upon Industry and the government, the Left Opposition is bringing in its wake what brutality and coarseness, vhat creased by tens of thousands in recent local, state and national. swift revulsion against these latest meth disregard of the interests of the proletar weeks, face a future of increased misery, ods of the Stalinist bureaucracy toward iat of the Russian October, mark this Organise Unemployed on Elementary Issues degradation, poverty and starvation. U. S. Under the conditions it is possible to the Leninist Bosheviks in the U. S. R. Stalin and his conscienceless cliinovnlks, capitalism offers fine words to the unem The worker-Communists and the proletar the Molotovs, Thaelmanns, Fosters, Minors, develop a broad movement on behalf of the ployed but no work or compensation. In unemployed masses, as has been previously ian forces throughout the world are put Cac-hiLs! With one hand they wave the November 1929, immediately after the Wall shown by the Militant. -

Learning from Ambiguously Labeled Images

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Technical Reports (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science January 2009 Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Timothee Cour University of Pennsylvania Benjamin Sapp University of Pennsylvania Chris Jordan University of Pennsylvania Ben Taskar University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports Recommended Citation Timothee Cour, Benjamin Sapp, Chris Jordan, and Ben Taskar, "Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images", . January 2009. University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science Technical Report No. MS-CIS-09-07 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/902 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Abstract In many image and video collections, we have access only to partially labeled data. For example, personal photo collections often contain several faces per image and a caption that only specifies who is in the picture, but not which name matches which face. Similarly, movie screenplays can tell us who is in the scene, but not when and where they are on the screen. We formulate the learning problem in this setting as partially-supervised multiclass classification where each instance is labeled ambiguously with more than one label. We show theoretically that effective learning is possible under reasonable assumptions even when all the data is weakly labeled. Motivated by the analysis, we propose a general convex learning formulation based on minimization of a surrogate loss appropriate for the ambiguous label setting. We apply our framework to identifying faces culled from web news sources and to naming characters in TV series and movies. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology.