Determinismssemicompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Libertarianism Illusionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Linguistics

Philosophy of Linguistics Brian Rabern Philosophy DSB 4.04c 0131 651 5178 [email protected] Geoff Pullum Linguistics DSB 2.23 0131 650 3603 [email protected] Meetings The class meetings are from 11:00 to 13:00 each Wednesday from 19th September to 28th November in Old Library 2.19, Geography building, Old Infirmary complex (weeks 1–3 and 6–11) and in 01M.469 Teaching Room 12 (Doorway 3), Medical School building. Class meetings are mandatory. Readings Required reading is to be done before the class meets; background reading to be studied as time and specific interests permit. Assessment (i) short paper (1000-1500 words) to be turned in by 5 p.m. on Monday 15th October (topics will be provided); (ii) final essay examination with choice of questions from the whole of the course. Week 1 (19th September; Old Library 2.19): Introduction What linguistics is. Linguistics as a special science. Syntax and semantics as conceived in logic. Charles Morris’s trichotomy of syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Philosophy of science applied to linguistics. Required reading • Hunter, Geoffrey (1971) Metalogic: An Introduction to the Metatheory of Standard First Order Logic (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 4–13. Background reading • Stainton, Robert (2014) ‘Philosophy of linguistics’, Oxford Handbooks Online. Online at https://works.bepress.com/robertstainton/126/ Week 2 (26th September; Old Library 2.19): Language and languages The metaphysics of linguistics. The vexed question of whether language should be regarded as psychological, social, or purely abstract. The descriptive linguistics of the American structuralists and the mentalist/cognitive backlash; ‘God’s truth’ (realism) vs. -

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

Linguistic Determinism and Mutability: the Sapir-Whorf "Hypothesis" and Intercultural Communication

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 403 761 FL 024 384 AUTHOR van Troyer, Gene TITLE Linguistic Determinism and Mutability: The Sapir-Whorf "Hypothesis" and Intercultural Communication. PUB DATE Dec 94 NOTE 18p. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Journal Articles (080) JOURNAL CIT JALT Journal; v16 n2 p163-78 Dec 1994 EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; *Intercultural Communication; *Language Research; *Linguistic Theory; Research Methodology; Scientific Methodology IDENTIFIERS *Sapir (Edward); Whorf (Benjamin Lee); *Whorfian Hypothesis ABSTRACT The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, long considered a factor in intercultural communication, is discussed. Empirical studies that have tended to validate the hypothesis are reviewed, and the hypothesis is then considered from the standpoint of empirical and scientific research requirements. It is shown that the hypothesis has never been formally defined for testing, and therefore does not exist as a scientifically testable thesis. As a result, all studies that have attempted to interpret empirical data accorded to the hypothesis are either flawed or invalid because they have tested something other than the hypothesis. It is concluded that the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis exists only as a notion, and has no meaningful relation to intercultural communication. Includes an abstract in Japanese. Contains 22 references. (Author/MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION AND CENTER (ERIC) DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL This document has been reproduced as HAS BE N GRANTEDBY ceived from the person or organization originating it. Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. -

Thoughts in Motion

! ! "# $ % & #''# #() (*+,(( - . / 0& /& &1 , ' ,2 &##/ # ,# & 3, ,/4 # 56/'# / & , , & , ' & / & ' , # # # & 7 '& & ' 3#/(((6,0 '# & / # 8 # 8 # & '# , ' & # '& ,% & # / # # & # ,9& / '# #' '# , 3 6, 3 & 6 # ,% / # / /& '# # 3 & '4 56'/ #/ ' # # & ' 34 56, # , ' & ,2 : # 3 6 & # '; # , / # ' &' ; 3,,/ <6,2 / ' & ' / / , ! (* 7== ,',= &< > 7 ' 777&?@* 2$-@*A@*B?@A(* 2$-@*A@*B?@A(AA 2-?((C@ % & #/(B@ Thoughts in Motion The Role of Long-Term L1 and Short-Term L2 Experience when Talking and Thinking of Caused Motion Guillermo Montero-Melis Centre for Research on Bilingualism Department of Swedish Language and Multilingualism Stockholm University Doctoral Dissertation 2017 Centre for Research on Bilingualism Department of Swedish Language and Multilingualism Stockholm University Copyright: Guillermo Montero-Melis Printing: Universitetsservice AB, Stockholm 2017 Correspondence: SE 106 91 Stockholm www.biling.su.se ISBN 978-91-7649-807-1 (print) ISBN 978-91-7649-808-8 (electronic) ISSN 1400-5921 A mi abuelo Manuel Melis, por su amor al saber Acknowledgements Two persons have mainly guided my efforts. I am deeply grateful to my main advisors, Manne -

Linguistic Relativity Phillip Wolff∗ and Kevin J

Advanced Review Linguistic relativity Phillip Wolff∗ and Kevin J. Holmes The central question in research on linguistic relativity, or the Whorfian hypothesis, is whether people who speak different languages think differently. The recent resurgence of research on this question can be attributed, in part, to new insights about the ways in which language might impact thought. We identify seven categories of hypotheses about the possible effects of language on thought across a wide range of domains, including motion, color, spatial relations, number, and false belief understanding. While we do not find support for the idea that language determines the basic categories of thought or that it overwrites preexisting conceptual distinctions, we do find support for the proposal that language can make some distinctions difficult to avoid, as well as for the proposal that language can augment certain types of thinking. Further, we highlight recent evidence suggesting that language may induce a relatively schematic mode of thinking. Although the literature on linguistic relativity remains contentious, there is growing support for the view that language has a profound effect on thought. 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. WIREs Cogn Sci 2010 DOI: 10.1002/wcs.104 INTRODUCTION rise to several logical paradoxes.6 However, a recent resurgence of research in this area has uncovered olk psychology tells us that human cognition subtle and intriguing interactions between language depends on language, and further, that this F and thought, leading to a number of more nuanced dependency creates differences in thought across versions of the proposal. language communities. Although often mistaken, folk psychology appears to be at least partially correct in this case. -

Theory Reflections: Linguistic Determinism/Relativism

Theory Reflections: Linguistic Determinism/Relativism The Theory The theory of linguistic determinism and relativity presents a two-sided phenomenon: Does the specific language (and culture) we are exposed to in childhood determine, in fact, how we perceive the world, how we think, and how we express ourselves? If this is so, then, it must also be the case that each language (and the culture it represents) necessarily provides its speakers with a specific and differing view of that same world, a different way of thinking, and a different way of expressing. This notion is related to a parallel issue that has existed throughout the centuries—are there also universal absolutes that transcend all linguistic (and cultural) particulars? Recent research suggests there may be elements of both. Linguistic determinism came to the attention of linguists and anthropologists during the 1930s, prompted by the work of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Using prevailing linguistic approaches of his time, Whorf, who studied indigenous languages, found surprising contrasts with European tongues in terms of how they reflected and spoke about reality (e.g., how they segment the time continuum, construct lexical hierarchies and, in short, encode a different view of the world, or Weltanschauung). The Whorf-Sapir hypothesis, as it came to be known (Sapir was his teacher), gained increasing attention and prompted the notion of language determinism/relativity. In other words, the language we are born to has a direct effect upon how we conceptualize, think, interact, and express—a direct relationship between human language and human thinking This notion has remained at the center of a debate for more than half a century. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Impact of language on thought and worldview, especially in the domains of time and space“ verfasst von / submitted by Keun Jun Song angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien 2016 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 812 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium English Language and Linguistics degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Nikolaus Ritt Table of contents page Abstract………………………………….…………………………....i Acknowledgment……………………………………………………..ii List of tables…………………………………………………..……...iii List of figures…………………………………………….…………..iv 1. Introduction…………………………………………………….......1 2. Purpose of the research…………………………………………….3 3. Methodology of the research………………………………………4 4. Theory: linguistic relativity…………………………………….…..7 4.1. Advent of the theory: Sapir-Whorf hypothesis…………….……….……8 4.1.1. Sub-classification of linguistic relativity based on relevant hypotheses………………………………………………………….......13 4.1.1.1. Language as a prototype of mental activities……………….14 4.1.1.2. Linguistic determinism……………………………………..16 4.1.1.3. Thinking before language…………………………………..16 4.1.1.4. Thinking with language…………………………………….17 4.1.1.5. Thinking after language…………………………………….18 4.2. Cognitive linguistics and the theory of linguistic relativity………….…20 4.3. Language as a matrix for thought………………………………….........25 4.4. Language and worldview………………………………………..……...26 4.4.1. World-perceiving………………………………………...……….31 4.4.2. World-conceiving……………………………………………..…..32 4.4.3. Cultural mindset…………………………………………………..32 4.4.4. Personal world…………………………………………….......….35 4.4.5. Perspective………………………………………………..………36 5. Mechanism of linguistic relativity………………………….….............37 6. -

A Rationalist Argument for Libertarian Free Will

A rationalist argument for libertarian free will Stylianos Panagiotou PhD University of York Philosophy August 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I give an a priori argument in defense of libertarian free will. I conclude that given certain presuppositions, the ability to do otherwise is a necessary requirement for substantive rationality; the ability to think and act in light of reasons. ‘Transcendental’ arguments to the effect that determinism is inconsistent with rationality are predominantly forwarded in a Kantian manner. Their incorporation into the framework of critical philosophy renders the ontological status of their claims problematic; rather than being claims about how the world really is, they end up being claims about how the mind must conceive of it. To make their ontological status more secure, I provide a rationalist framework that turns them from claims about how the mind must view the world into claims about the ontology of rational agents. In the first chapter, I make some preliminary remarks about reason, reasons and rationality and argue that an agent’s access to alternative possibilities is a necessary condition for being under the scope of normative reasons. In the second chapter, I motivate rationalism about a priori justification. In the third chapter, I present the rationalist argument for libertarian free will and defend it against objections. Several objections rest on a compatibilist understanding of an agent’s abilities. To undercut them, I devote the fourth chapter, in which I give a new argument for incompatibilism between free will and determinism, which I call the situatedness argument for incompatibilism. If the presuppositions of the thesis are granted and the situatedness argument works, then we may be justified in thinking that to the extent that we are substantively rational, we are free in the libertarian sense. -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011). -

Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Daniel C. Dennett Illusionism as the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Using a parallel with stage magic, it is argued that far from being seen as an extreme alternative, illusionism as articulated by Frankish should be considered the front runner, a conservative theory to be developed in detail, and abandoned only if it demonstrably fails to account for phenomena, not prematurely dismissed as ‘counter- intuitive’. We should explore the mundane possibilities thoroughly before investing in any magical hypotheses. Keith Frankish’s superb survey of the varieties of illusionism pro- vokes in me some reflections on what philosophy can offer to (cog- nitive) science, and why it so often manages instead to ensnarl itself in an internecine battle over details in ill-motivated ‘theories’ that, even Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 if true, would be trivial and provide no substantial enlightenment on any topic, and no help at all to the baffled scientist. No wonder so For personal use only -- not for reproduction many scientists blithely ignore the philosophers’ tussles — while marching overconfidently into one abyss or another. The key for me lies in the everyday, non-philosophical meaning of the word illusionist. An illusionist is an expert in sleight-of-hand and the other devious methods of stage magic. We philosophical illusion- ists are also illusionists in the everyday sense — or should be. That is, our burden is to figure out and explain how the ‘magic’ is done. As Frankish says: Illusionism replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem — the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and Correspondence: Daniel C. -

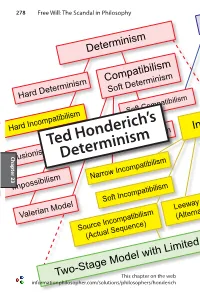

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom