The Minister's Wife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

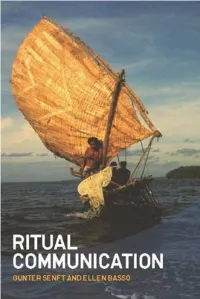

Ritual Communication W E N N E R -G R E N I N T E R N a T I O N a L S Y M P O Si U M S E R I E S

Ritual Communication W ENNER -G REN I NTERNAT I ONAL S YMPO si UM S ER I E S . Series Editor: Leslie C. Aiello, President, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, New York. ISSN: 1475-536X Previous titles in this series: Anthropology Beyond Culture Edited by Richard G. Fox & Barbara J. King, 2002 Property in Question: Value Transformation in the Global Economy Edited by Katherine Verdery & Caroline Humphrey, 2004 Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listening and Modernity Edited by Veit Erlmann, 2004 Embedding Ethics Edited by Lynn Meskell & Peter Pels, 2005 World Anthropologies: Disciplinary Transformations within Systems of Power Edited by Gustavo Lins Ribeiro and Arturo Escobar, 2006 Sensible Objects: Colonialisms, Museums and Material Culture Edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden and Ruth B. Phillips, 2006 Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition and Interaction Edited by N. J. Enfield and Stephen C. Levinson, 2006 Where the Wild Things Are Now: Domestication Reconsidered Edited by Rebecca Cassidy and Molly Mullin, 2007 Anthropology Put to Work Edited by Les W. Field and Richard G. Fox, 2007 Indigenous Experience Today Edited by Marisol de la Cadena and Orin Starn Since its inception in 1941, the Wenner-Gren Foundation has convened more than 125 international symposia on pressing issues in anthro pology. These symposia affirm the worth of anthropology and its capacity to address the nature of humankind from a wide variety of perspectives. Each symposium brings together participants from around the world, representing different theoretical disciplines and traditions, for a week-long engagement on a specific issue. The Wenner-Gren International Symposium Series was initiated in 2000 to ensure the publication and distribution of the results of the foundation’s International Symposium Program. -

Cain and Abel - Wikilivres

ﺑ_ ﻭھﺑ /https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki ﺑ ﻭھﺑ - ﻭ، ا اة ﻣ ﻭ، ا اة 1 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ا اﺩي ﻭا 2 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ام 3 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ﺭﻭات اﻣم اﺩق 4 اا 5 ط وھ ھ ن ذ ا ا، ﻭھ أﻭل اﺑ ﺩم ﻭاء . ن ﺑ ﻣً ﺑﺭض أﻣ ھﺑ ن ﺭا ، ﻭ م ﺭا أن ا ﷲ ﻣ اﺑ . ل اب : ﻭث ﻣ ﺑ أم، أن ﺑ م ﻣ ﺭ اﺭض ﺑﻧً ب . ﻭم ھﺑ أً ﻣ أﺑﺭ ﻭﻣ ﻧِ . اب إ ھﺑ ﻭﺑﻧ، ﻭ إ ﺑ ﻭﺑﻧ . ﻅ ﺑ اً، ﻭ ﻭ. ]1[ ﻭ اب إ ﺑن ﺑ ﻧ ن ﻣ ن ﻭھ اﺑ اﻣ ]2[ أﻣ ھﺑ . ل اب : ﺑن م ھﺑ ذﺑ أ ﻣ ﺑ . ُ ِ أﻧ ﺑﺭٌ إذ ِ ﷲ اﺑ. ﺑ اﺩ إﻧ ﺑب ﻭ . اب ﺑن ﺑ ﻅ ﺑ اً ﻭ ﻭ. ]3[ م أﺧ ھﺑ ا ﻭ، ل اب أ ھﺑ أﺧك؟ ل أ؛ أﺭس أﻧ ﺧ . ل : ﻣذا ؟ ﺻت ﺩم أﺧ ﺻﺭخ ﻣ اﺭض . ن، ﻣن أﻧ ﻣ اﺭض ا ھ ﺩم أﺧ ﻣ ك . ﻣ ْ اﺭض ﺩ . ً ﻭھﺭﺑً ن اﺭض. ]4[ ْ ذھ ﷲ اآن ﺩﻭن ذ ا ﺻا ﺑ ا ﺑﺻ اﺑ آﺩم ل : َ و ْا لُ َ! َ ْ ِ ْم َ ََ ْا َ ْ َآدَم ِ ْ َ ق إِذ َ َر ُ ْر َ ً َ ُ ُ َل ِن َ َ َ َ أ َ ِد ِھ َ َ وَ ْم َُ َ ْل ِ َن َا)' ِر َ َ ل َ & ْ ُ َ َك َ َ ل إِ َ َ َ َ لُ ّ $ُ ِ َن ْا ُ ِ َن 0َِن َ َ. -

Mourning Practices on Facebook: Facebook Shrines and Other Rituals of Grieving in the Digital Age

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Anthropology Theses and Dissertations Anthropology Spring 2021 MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE Sydney Yeager [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Yeager, Sydney, "MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE" (2021). Anthropology Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds/15 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE Approved by: _______________________________________ Dr. Caroline Brettell Professor and Chair, Anthropology ___________________________________ Dr. Nia Parson Associate Professor, Anthropology ___________________________________ Dr. Jill DeTemple Professor and Chair, Religious Studies ___________________________________ Prof. Phil Frana Associate Dean, Honors College, James Madison University MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Cultural Anthropology by Sydney Yeager B.S., History, University of Central Arkansas Master of Arts in Medical Anthropology, Southern Methodist University May 15, 2021 Copyright (2020) Sydney Yeager All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Death comes to us all in time. -

Dandyism and the Haunting of Contemporary Masculinity

"THE IDEA OF BEAUTY IN THEIR PERSONS:" DANDYISM AND THE HAUNTING OF CONTEMPORARY MASCULINITY Darin Kerr A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Juan Bes Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Lesa Lockford © 2015 Darin Kerr All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this dissertation, I argue for the dandy as a spectral force haunting contemporary masculinity. Using the framework of Derridean hauntology, I posit that certain contemporary performances of masculinity engage with discourses of dandyism, and that such performances open up a space for the potential expression of a masculine identity founded on an alterity to hegemonic gender norms. The basis for this alterity derives from the philosophical underpinnings of dandyism as articulated by its most prominent nineteenth century theorizers. As a result, I divide my study into two halves: the first focuses on a close reading of texts by Balzac, d’Aurevilly, and Baudelaire; the second centers on three case studies illustrating the spectral nature of dandiacal performance in relationship to contemporary masculinity. Chapter One establishes the framework for my argument, articulating the way in which both nineteenth century French philosophical dandyism and Derrida’s concept of hauntology, particularly his “three things of the thing” (mourning, language, and work), serves to structure the rest of the study. Chapters, Two, Three, and Four, which constitute Part I, provide close readings of texts by Balzac, d’Aurevilly, and Baudelaire, respectively. Chapters Five, Six, and Seven form Part II, and consist of individual case studies examining the spectral traces of dandyism in performances of masculinity by three contemporary celebrities. -

What Am I Worth? Value

Value What Am I Worth? Value This world sometimes leaves us feeling kicked, empty, and wondering if it’s all worth it—or if we are worth it. But God leaves no doubt of the tremendous value He places on every human life, including yours. Definition Value • The regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something. Painting the Picture The First Mourning, 1888 by William-Adolphe Bouguereau Cain and Abel • Genesis 4 • 1 And the man knew Eve his wife; and she conceived, and bare Cain, and said, I have gotten a man with the help of Jehovah. 2 And again she bare his brother Abel. And Abel was a keeper of sheep, but Cain was a tiller of the ground. Cain and Abel • 4 But Abel brought [an offering of] the [finest] firstborn of his flock and the fat portions. And the LORD had respect (regard) for Abel and for his offering; 5 but for Cain and his offering He had no respect. So Cain became extremely angry (indignant), and he looked annoyed and hostile. 6 And the LORD said to Cain, “Why are you so angry? And why do you look annoyed? Amplified Bible Cain and Abel • 7 If you do well [believing Me and doing what is acceptable and pleasing to Me], will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well [but ignore My instruction], sin crouches at your door; its desire is for you [to overpower you], but you must master it.” 1 Peter 5:8 That enemy of yours, the devil, prowls The devil hasn’t changed around like a roaring lion [fiercely hungry], seeking someone to devour Cain and Abel • 8 Cain talked with Abel his brother [about what God had said]. -

Guideposts Through Grief Helpful Information for the Recently Bereaved

GUIDEPOSTS THROUGH GRIEF HELPFUL INFORMATION FOR THE RECENTLY BEREAVED The days, weeks and months that follow the death of a loved one can sometimes be surprisingly difficult. Coping with the losses and challenges associated with the • Community Care Hospice death of a loved one can feel akin to being routed miles off the Interstate and into • Hospice of Central Ohio unfamiliar territory without a map. We believe that just as a good map could be quite • Ohio’s Community Mercy Hospice useful on an unexpected road detour, having a “map” as you enter the territory of • Ohio’s Hospice at United Church Homes grief and loss can be very beneficial as well. While everyone’s grief experience will • Ohio’s Hospice LifeCare be uniquely personal, knowing what the “territory of loss and grief” looks like can • Ohio’s Hospice Loving Care be very reassuring. Much unnecessary suffering can be prevented through accurate • Ohio’s Hospice of Butler & Warren Counties information and realistic expectations. • Ohio’s Hospice of Dayton • Ohio’s Hospice of Fayette County The articles that follow are designed to provide you and your family with helpful • Ohio’s Hospice of Miami County information about various aspects of the grieving process. Also included is information about grief support services available through our Pathways of Hope grief “GRIEF IS NOT A DISORDER, counseling centers as well as a list of helpful books and internet resources. You will A DISEASE OR A SIGN notice that the center insert provides current information about specific grief support or grief education groups as well as information related to upcoming memorial OF WEAKNESS. -

Ulysses Quotidian Micro-Spectacles

QUOTIDIAN MICRO-SPECTACLES: ULYSSES AND FASHION PING-TA KU A thesis Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University College London Department of English Language and Literature University College London September 2014 1 I, PING-TA KU, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. The 5th of September, 2014 2 Abstract Quotidian Micro-Spectacles: Ulysses and Fashion wishes to make a contribution to Joycean studies in the research area that has been known as cultural studies. Over nearly three decades, there have been seminal works in this research area, such as Cheryl Herr’s Joyce’s Anatomy of Culture, R. Brandon Kershner’s The Culture of Joyce’s Ulysses, Garry Leonard’s Advertising and Commodity Culture in Joyce, and articles featured in James Joyce Quarterly Volume 30 (Fall 1992-Summer/Fall 1993); this thesis focuses on one specific aspect of commodity culture––that is, fashion items––in Ulysses, believing that a microscopic scrutiny at the details of these fashion items would reveal how Joyce’s innovative language and narrative in Ulysses are rooted in and interlaced with technologies that have inconspicuously yet greatly changed people’s daily life during the period of time when Joyce was writing Ulysses. Through the microscopic gaze, this thesis identifies a colonial phenomenon that is ubiquitous amongst Ulysses’s mist of language-game, that is, the omnipresence of English fashion: Stephen Dedalus’s adherence to mourning dress, Leopold Bloom’s meticulousness about dress codes, Gerty MacDowell’s obsession with dame fashion, the Circean mise-en-scène of millinery spectacles, and Molly Bloom’s desire for Edwardian lingerie. -

In the Beginning: Art from the Book of Genesis

In the Beginning: Art from the Book of Genesis Cain and Abel (Genesis 4) Julian Bell (British, (1952-), Cain and Abel, 2015 Genesis 4 4 Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have gotten a man with the help of the LORD.” 2 And again, she bore his brother Abel. Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a worker of the ground. 3 In the course of time Cain brought to the LORD an offering of the fruit of the ground, 4 and Abel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat portions. And the LORD had regard for Abel and his offering, 5 but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his face fell. 6 The LORD said to Cain, “Why are you angry, and why has your face fallen? 7 If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door. Its desire is contrary to you, but you must rule over it.” 8 Cain spoke to Abel his brother. And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him. 9 Then the LORD said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother's keeper?” 10 And the LORD said, “What have you done? The voice of your brother's blood is crying to me from the ground. 11 And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother's blood from your hand. -

On Love, Loss, and Virginity

The First Time and the Mourning After: On Love, Loss, and Virginity by Jonathan Andrew Allan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Andrew Allan 2012 The First Time and the Mourning After: On Love, Loss, and Virginity Jonathan Andrew Allan Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto 2012 Abstract In “The First Time and the Mourning After: On Love, Loss, and Virginity,” I consider the question, mythology, and importance of the first time. My study opens theoretically and polemically with a concern for the meanings of the first time, why we reify the first time, why we mythologise the first time, and why we narrate the first time. In this opening, I also develop an argument for, what I call, “the flirtatious method,” a method, which pays little attention to commitment, but instead finds productive comfort in flirting with various theoretical postures, textual examples, and varying belief systems. The goal, thus, of the flirtatious method is to consider a problem, like the first time, from a variety of, and at times, competing discourses. In the chapters that follow, I begin to theorise one of the most important first times: the loss of virginity, and more specifically, male virginity. I argue that all first times must include paranoia, jouissance, hysteria, and mourning. In the next chapter, “On the First Love and First Loss,” I begin to theorise the first time in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and J. -

Said Mr. Polly, and Then for Ac

THE HISTORY OF MR. POLLY BY H. G. Wells Chapter the First Beginnings, and the Bazaar I “Hole!” said Mr. Polly, and then for a change, and with greatly increased emphasis: “’Ole!” He paused, and then broke out with one of his private and peculiar idioms. “Oh! Beastly Silly Wheeze of a Hole!” He was sitting on a stile between two threadbare looking fields, and suffering acutely from indigestion. He suffered from indigestion now nearly every afternoon in his life, but as he lacked introspection he projected the associated discomfort upon the world. Every afternoon he discovered afresh that life as a whole and every aspect of life that presented itself was “beastly.” And this afternoon, lured by the delusive blueness of a sky that was blue because the wind was in the east, he had come out in the hope of snatching something of the joyousness of spring. The mysterious alchemy of mind and body refused, however, to permit any joyousness whatever in the spring. He had had a little difficulty in finding his cap before he came out. He wanted his cap—the new golf cap—and Mrs. Polly must needs fish out his old soft brown felt hat. “’Ere’s your ’at,” she said in a tone of insincere encouragement. He had been routing among the piled newspapers under the kitchen dresser, and had turned quite hopefully and taken the thing. He put it on. But it didn’t feel right. Nothing felt right. He put a trembling hand upon the crown of the thing and pressed it on his head, and tried it askew to the right and then askew to the left. -

Frail and Faithful the Character of Humanity in Gen 3—11

Frail and Faithful The Character of Humanity in Gen 3—11 “What sort of thing am I?” Every creature of character eventually asks this question. The Greek philosopher Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” “I think, therefore I am,” proclaimed French philosopher, Rene Descartes, after long and skeptical musings. When Jean Valjean asks it dramatically at a turning point in is life in Les Miserables, he answers, “Who am I?...My soul belongs to God, I know / I made that bargain long ago / He gave / me hope, when hope was gone / He gave me strength to journey on! / Who am I? / Who am I? /I am Jean Valjean!” While living out the last days of his prison stay under the Nazis, the German churchman Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote a poem called “Who Am I?” In it, he reflects on the high regard others have for him, compared with his own feelings of inadequacy and failure. He closes with the one thing of which he is sure: Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine. Whoever I am, Thou knowest, O God, I am thine!” What is it to be human? What is it to be you? Genesis 3 through 11 introduce us to both the frail and the faithful in us. Let’s read on! Part One – Freedom and “The Fall” How free are you? Do your choices feel like they are really yours to make, or are they determined by other agents or forces? What does God have to do with your free choosing? What does true freedom feel like? In Genesis 3, we get our first window into human freedom. -

The Early World of Genesis

UNIT 3 The Early World of Genesis Lessons in This Unit Connection to the ӹ Lesson 1: Exploring the Early World Catechism of the of Genesis with Sacred Art Catholic Church ӹ Lesson 2: The Story of Creation ӹ Lesson 3: Adam and Eve Lesson 1 ӹ Lesson 4: Cain and Abel ӹ 753-757, 760-761, 845, 1219 ӹ Lesson 5: Noah and the Great Flood Lesson 2 Scripture Studied in This Unit ӹ 279-361, 1147, 2169- ӹ Genesis 1:1-3:24 2172, 2402 ӹ Genesis 4:1-22 Lesson 3 ӹ Genesis 5:3 ӹ 374-379, 388-389, 396- ӹ Genesis 6:5-22 406, 410-412 ӹ Genesis 8:20 Lesson 4 ӹ Genesis 9:9-10 ӹ 901, 1849-1850, 1865, Genesis 7:1-24 ӹ 2099-2100 ӹ Genesis 8:1-22 ӹ Genesis 9:1-17 Lesson 5 ӹ 56-58, 71, 338, 845, ӹ Genesis 9:8-17 1094, 1219 ӹ Numbers 3:5-8 ӹ Psalm 8:4-6 ӹ Luke 21:3-4 ӹ Acts 22:16 ӹ Romans 7:15 ӹ 1 Peter 3:19-21 ӹ 1 John 4:7, 20-21 UNIT 3 OVERVIEW 193 Introduction rom the very beginning, God has desired we are free to read the story of creation Ffor the human race to come together in according to the plain meaning of the a loving relationship with each other and words on the page, it is unlikely. Rather, with Him. God created mankind with this the story of creation communicates to us truth inscribed into the human body, as important truths about God, ourselves, and male and female.