Love Story /By a Bushman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Inter-Cultural Insights Christian Reflections on Racism, Hospitality and Identity from the Island of Ireland

Inter-Cultural Insights Christian reflections on racism, hospitality and identity from the island of Ireland RESOURCE BOOKLET All-Ireland Churches’ Consultative Meeting on Racism/Irish Inter-Church Meeting Edited by SCOTT BOLDT March 2008 Contents Inter-Cultural Insights: Introduction 4 A series of Christian reflections on racism, hospitality and identity from the island of Ireland. Seeking Refuge And A Welcome 6 RESOURCE BOOKLET A Northern Perspective 8 Resisting Racism 10 Reflection On Racism 12 On Being Black 13 Published by The Women At The Well 15 the All-Ireland Churches Consultative Meeting on Racism (AICCMR) Being, Identity And Belief 17 September 2008 Being Malay And Being Christian 19 God’s People Are All Nations 21 © AICCMR Material from this publication may be reproduced in whole or The Good Samaritan 23 in part without permission, provided that it is not altered in Even If Always A Stranger 25 any way, and that the authorship of the material is acknowledged. Stranger In A Strange Land? 27 Belonging-Connected-Noticed 29 PRINTER : Dorman & Sons A Holy Dream 31 Challenged By Ignorance: The Pharisee And The Tax Collector 33 DESIGN : Spring Graphics Jesus The Refugee 36 The Ruth Story 39 Appendix 42 Project supported by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation 2 | INTER-CULTURAL INSIGHTS INTER-CULTURAL INSIGHTS | 3 Introduction This series of Christian reflections was assembled by the All-Ireland Churches’ The All-Ireland Churches Consultative Meeting on Racism (AICCMR)’s aim is to encourage Consultative Meeting on Racism (AICCMR) to offer fresh insights into scripture and to and enable the Churches in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland: highlight: • personal experiences of racism in Ireland, • To acknowledge the need to tackle racial justice issues in a more systematic and • perspectives on the challenge of identity and difference, and holistic fashion. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 29 | 2016 Varia The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini Robert Parker and Scott Scullion Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2399 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2399 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2016 Number of pages: 209-266 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Robert Parker and Scott Scullion, « The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini », Kernos [Online], 29 | 2016, Online since 01 October 2019, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2399 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2399 This text was automatically generated on 10 December 2020. Kernos The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini 1 The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini Robert Parker and Scott Scullion For help and advice of various kinds we are very grateful to Jim Adams, Sebastian Brock, Mat Carbon, Jim Coulton, Emily Kearns, Sofia Kravaritou, Judith McKenzie, Philomen Probert, Maria Stamatopoulou, and Andreas Willi, and for encouragement to publish in Kernos Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge. Introduction 1 The interest for students of Greek religion of the large opisthographic stele published by J.C. Decourt and A. Tziafalias, with commendable speed, in the last issue of Kernos can scarcely be over-estimated.1 It is datable on palaeographic grounds to the second century BC, perhaps the first half rather than the second,2 and records in detail the rituals and rules governing the sanctuary of a goddess whose name, we believe, is never given. -

Educational Communities, Arts-Based Inquiry, & Role-Playing: an American

Educational Communities, Arts-Based Inquiry, & Role-Playing: An American Freeform Exploration with Professional & Pre-Service Art Educators DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason Cox Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education, and Policy The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Christine Ballengee-Morris, Advisor, Ph.D., Clayton Funk, Ed.D., Karen Hutzel, Ph.D., Jennifer Richardson, Ph.D., Sydney Walker, Ph.D. Copyright by Jason Cox 2015 Abstract This research employs American freeform role-playing games as a media for participatory arts-based inquiry into the relationships and perspectives of professional and pre-service art educators. The role-played performances and participatory discourse re- imagine relationships within a collaboratively imagined educational community that parallel ones from the professional lives of art educators, such as those between school administrators, staff, teachers, students, and parents. Participants use the roles, relationships, and settings they construct to explore themes and situations that they identify as being present in educational communities. These situations represent points of intersection between members of an educational community, such as parent-teacher conferences, community advocacy meetings, or school field trips. The data from each experience takes the form of personal reflections, participant-created artifacts, and communal discourse. By assuming various roles and reflecting upon them, participants gain access to experiences and points of view that provoke reflection, develop leadership capabilities, and enhance their capacity for affecting change within an educational setting. ii Dedication To my wife Alissa and to all of our family & friends for making this journey possible. -

Interior Pages

REACHING FAMILIES FOR JESUS DISCIPLESHIP AND SERVICE WILLIE AND ELAINE OLIVER with DRS CLAUDIO AND PAMELA CONSUEGRA ALINA BALTAZAR, CLAUDIO AND PAMELA CONSUEGRA, DAWN JACOBSON-VENN, S. JOSEPH KIDDER, LINDA MEI LIN KOH, SAUSTIN SAMPSON MFUNE, DEREK J. MORRIS, ALANZO SMITH, MARIJA TRAJKOVSKA North American Division Corporation of the Seventh-day Adventist Church Editors: Drs. Claudio and Pamela Consuegra A General Conference Department of Family Ministries publication Editors: Willie and Elaine Oliver Managing Editor: Dwain N. Esmond Editorial Assistants: Dawn Venn, Ayakha Mokgwane Design and Formatting: Daniel Taipe Contributors: Alina Baltazar, Claudio and Pamela Consuegra, Dawn Jacobson-Venn, S. Joseph Kidder, Linda Mei Lin Koh, Saustin Sampson Mfune, Derek J. Morris, Alanzo Smith, Marija Trajkovska Other Family Ministries Planbooks in this series: Reaching Families for Jesus: Growing Disciples Reach the World: Healthy Families for Eternity Revival and Reformation: Building Family Memories Revival and Reformation: Families Reaching Up Revival and Reformation: Families Reaching Out Revival and Reformation: Families Reaching Across Available from AdventSource 5120 Prescott Avenue Lincoln, NE 68506 www.adventsource.org 402.486.8800 Unless otherwise noted, Scripture is taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ©2017 Department of Family Ministries General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists 12501 Old Columbia Pike Silver Spring, MD 20904, USA [email protected] Website: family.adventist.org All rights reserved. The handouts in this book may be used and reproduced in local church printed matter without permission from the publisher. It may not, however, be used or reproduced in other books or publications without prior permission from the copyright holder. -

Songs of the Classical Age

Cedille Records CDR 90000 049 SONGS OF THE CLASSICAL AGE Patrice Michaels Bedi soprano David Schrader fortepiano 2 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 049 S ONGS OF THE C LASSICAL A GE FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN MARIA THERESIA VON PARADIES 1 She Never Told Her Love.................. (3:10) br Morgenlied eines armen Mannes...........(2:47) 2 Fidelity.................................................... (4:04) WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 3 Pleasing Pain......................................... (2:18) bs Cantata, K. 619 4 Piercing Eyes......................................... (1:44) “Die ihr des unermesslichen Weltalls”....... (7:32) 5 Sailor’s Song.......................................... (2:25) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN VINCENZO RIGHINI bt Wonne der Wehmut, Op. 83, No. 1...... (2:11) 6 Placido zeffiretto.................................. (2:26) 7 SOPHIE WESTENHOLZ T’intendo, si, mio cor......................... (1:59) ck Morgenlied............................................. (3:24) 8 Mi lagnerò tacendo..............................(1:37) 9 Or che il cielo a me ti rende............... (3:07) FRANZ SCHUBERT bk Vorrei di te fidarmi.............................. (1:27) cl Frülingssehnsucht from Schwanengesang, D. 957..................... (4:06) CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES bl L’autre jour à l’ombrage..................... (2:46) PAULINE DUCHAMBGE cm La jalouse................................................ (2:22) NICOLA DALAYRAC FELICE BLANGINI bm Quand le bien-aimé reviendra............ (2:50) cn Il est parti!.............................................. (2:57) -

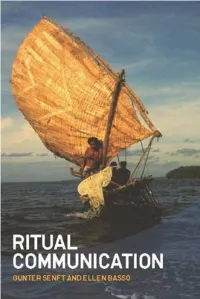

Ritual Communication W E N N E R -G R E N I N T E R N a T I O N a L S Y M P O Si U M S E R I E S

Ritual Communication W ENNER -G REN I NTERNAT I ONAL S YMPO si UM S ER I E S . Series Editor: Leslie C. Aiello, President, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, New York. ISSN: 1475-536X Previous titles in this series: Anthropology Beyond Culture Edited by Richard G. Fox & Barbara J. King, 2002 Property in Question: Value Transformation in the Global Economy Edited by Katherine Verdery & Caroline Humphrey, 2004 Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listening and Modernity Edited by Veit Erlmann, 2004 Embedding Ethics Edited by Lynn Meskell & Peter Pels, 2005 World Anthropologies: Disciplinary Transformations within Systems of Power Edited by Gustavo Lins Ribeiro and Arturo Escobar, 2006 Sensible Objects: Colonialisms, Museums and Material Culture Edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden and Ruth B. Phillips, 2006 Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition and Interaction Edited by N. J. Enfield and Stephen C. Levinson, 2006 Where the Wild Things Are Now: Domestication Reconsidered Edited by Rebecca Cassidy and Molly Mullin, 2007 Anthropology Put to Work Edited by Les W. Field and Richard G. Fox, 2007 Indigenous Experience Today Edited by Marisol de la Cadena and Orin Starn Since its inception in 1941, the Wenner-Gren Foundation has convened more than 125 international symposia on pressing issues in anthro pology. These symposia affirm the worth of anthropology and its capacity to address the nature of humankind from a wide variety of perspectives. Each symposium brings together participants from around the world, representing different theoretical disciplines and traditions, for a week-long engagement on a specific issue. The Wenner-Gren International Symposium Series was initiated in 2000 to ensure the publication and distribution of the results of the foundation’s International Symposium Program. -

November 18, 2018 M��� I��������� ��� ��� W��� W����� P����� C�����

MSGR. DAVID L. CASSATO, ADMINISTRATOR REV. MARTIN RESTREPO, PAROCHIAL VICAR Deacon Anthony Mammoliti, Pastoral Associate Ken Wodzanowski, Youth Minister 718-490-4469 - email: [email protected] S E O Mrs. Roseanne Bourke, DRE Telephone: 718-234-0041 R O M S Mon - Fri 9:00 AM - 8:00 PM Weekdays: 8:00AM (Italian) & 9:00AM - (July & August 8:30AM) Saturday 9:00 AM - 1:00 PM Saturdays: 8:30AM (Bilingual) & 5:30PM Vigil Telephone: 718-259-4636 Sundays: 9:00AM (English), 10:15AM (Italian), 11:30AM (English) Fax: 718-259-3066 1:00 PM (Spanish) [email protected] Holy Days: Please refer to the current bulletin. Website: stdominic-brooklyn.org S A S: Please call the M M rectory prior to surgery or in case of a serious illness. Mrs. Mary Carmosino, Music Director G P P P: Messa ogni primo Kateri Novoa, Cantor sabato del mese alle 10:30AM seguito da esposizione del Santissimo Sacramento, Rosario e Benedizione. S B: English: Call the M D: Holy Rosary every weekday after the Rectory during office hours to schedule an 8:00AM & 9:00AM Masses. Miraculous Medal Novena is every appointment for the Baptismal intake. In- Monday after the 9:00AM Mass. struction Class is required the Thursday two weeks before Baptism at 7:30PM. A B S: Fridays from 9:30AM-3:00PM—ending with Chaplet of Divine Mercy & Benediction. Español: Debe llamar primero a la Rectoría durante horas de oficina para hacer una cita. R E: Grades 1 - 8. Meets on Sundays at Los bautismos se celebran el Segundo Do- 10:00AM in the Church basement. -

Cain and Abel - Wikilivres

ﺑ_ ﻭھﺑ /https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki ﺑ ﻭھﺑ - ﻭ، ا اة ﻣ ﻭ، ا اة 1 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ا اﺩي ﻭا 2 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ام 3 ﺑ ﻭھﺑ ﺭﻭات اﻣم اﺩق 4 اا 5 ط وھ ھ ن ذ ا ا، ﻭھ أﻭل اﺑ ﺩم ﻭاء . ن ﺑ ﻣً ﺑﺭض أﻣ ھﺑ ن ﺭا ، ﻭ م ﺭا أن ا ﷲ ﻣ اﺑ . ل اب : ﻭث ﻣ ﺑ أم، أن ﺑ م ﻣ ﺭ اﺭض ﺑﻧً ب . ﻭم ھﺑ أً ﻣ أﺑﺭ ﻭﻣ ﻧِ . اب إ ھﺑ ﻭﺑﻧ، ﻭ إ ﺑ ﻭﺑﻧ . ﻅ ﺑ اً، ﻭ ﻭ. ]1[ ﻭ اب إ ﺑن ﺑ ﻧ ن ﻣ ن ﻭھ اﺑ اﻣ ]2[ أﻣ ھﺑ . ل اب : ﺑن م ھﺑ ذﺑ أ ﻣ ﺑ . ُ ِ أﻧ ﺑﺭٌ إذ ِ ﷲ اﺑ. ﺑ اﺩ إﻧ ﺑب ﻭ . اب ﺑن ﺑ ﻅ ﺑ اً ﻭ ﻭ. ]3[ م أﺧ ھﺑ ا ﻭ، ل اب أ ھﺑ أﺧك؟ ل أ؛ أﺭس أﻧ ﺧ . ل : ﻣذا ؟ ﺻت ﺩم أﺧ ﺻﺭخ ﻣ اﺭض . ن، ﻣن أﻧ ﻣ اﺭض ا ھ ﺩم أﺧ ﻣ ك . ﻣ ْ اﺭض ﺩ . ً ﻭھﺭﺑً ن اﺭض. ]4[ ْ ذھ ﷲ اآن ﺩﻭن ذ ا ﺻا ﺑ ا ﺑﺻ اﺑ آﺩم ل : َ و ْا لُ َ! َ ْ ِ ْم َ ََ ْا َ ْ َآدَم ِ ْ َ ق إِذ َ َر ُ ْر َ ً َ ُ ُ َل ِن َ َ َ َ أ َ ِد ِھ َ َ وَ ْم َُ َ ْل ِ َن َا)' ِر َ َ ل َ & ْ ُ َ َك َ َ ل إِ َ َ َ َ لُ ّ $ُ ِ َن ْا ُ ِ َن 0َِن َ َ. -

Mourning Practices on Facebook: Facebook Shrines and Other Rituals of Grieving in the Digital Age

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Anthropology Theses and Dissertations Anthropology Spring 2021 MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE Sydney Yeager [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Yeager, Sydney, "MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE" (2021). Anthropology Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds/15 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE Approved by: _______________________________________ Dr. Caroline Brettell Professor and Chair, Anthropology ___________________________________ Dr. Nia Parson Associate Professor, Anthropology ___________________________________ Dr. Jill DeTemple Professor and Chair, Religious Studies ___________________________________ Prof. Phil Frana Associate Dean, Honors College, James Madison University MOURNING PRACTICES ON FACEBOOK: FACEBOOK SHRINES AND OTHER RITUALS OF GRIEVING IN THE DIGITAL AGE A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Cultural Anthropology by Sydney Yeager B.S., History, University of Central Arkansas Master of Arts in Medical Anthropology, Southern Methodist University May 15, 2021 Copyright (2020) Sydney Yeager All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Death comes to us all in time. -

Ponies and Warhorses Recital Translations by Elizabeth Parcells

Ponies and Warhorses A concert of songs and opera arias by Mozart, Donizetti and Bellini with Elizabeth Parcells coloratura soprano and Alden Schell piano Program WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Das Veilchen (1756-1791) Abendempfindung An Cloe "Martern aller Arten" from the opera Entführung aus dem Serail GAETANO DONIZETTI Amiamo (1797-1848) La Gondola Barcarola "O nube! che lieve per l'aria ti aggiri" "Nella pace nel mesto riposa" from the opera Maria Stuarda Lamento per la morte di Bellini VINCENZO BELLINI Malinconia, Ninfa gentile (1801-1835) Vanne, o rosa fortunata Bella Nice, che d'amore Almen se non poss'io Per pietà, bell'idol mio Ma rendi pur contento "Ah! non credea mirarti" "Ah, non giunge" from the opera La Sonnambula Texts Das Veilchen The Violet A violet in the meadow stood_ Ein Veilchen auf der Wiese stand, with humble bow, demure and good, gebückt in sich und unbekannt: it was the sweetest violet. es war ein herzigs Veilchen. There came along a shepherdess with youthful step and happiness, Da kam ein' junge Schäferin who sang along the way this song. mit leichtem Schritt und munterm Sinn Oh! thought the violet, how I pine daher die Wiese her und sang. for natures beauty to he mine, if only for a moment, Ach! denkt das Veilchen, wär ich nur for then my love might notice me die schönste Blume der Natur, and on her bosom fasten me, I wish, if but a moment long. ach, nur ein kleines Weilchen, But, cruel fate! The maiden came, without a glance or care for him, bis mich das Liebchen abgepflückt she trampled down the voilet.