Dennis Richards on the WWII Bomber Offensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11 - Managing TE

Raul Susmel FINA 4360 – International Financial Management Dept. of Finance Univ. of Houston 4/16 Chapter 11 - Managing TE Last Lecture Managing TE Receivables-Sell forward future, buy put Payables- Buy forwards future, buy call Receivables-MMH borrow FC Payables-MMH borrow DC Last Lecture We will explore the choices that options provide. In our case: different strike prices. Hedging with Options We have more instruments to choose from => different strike prices (X): 1. Out of the money (cheaper) 2. In the money (more expensive) • Review: Reading Newspaper Quotes Typical Newspaper Quote PHILADELPHIA OPTIONS (PHLX is the exchange) Wednesday, March 21, 2007 (Trading Date) Calls Puts =>(Contracts traded) Vol. Last Vol. Last =>(Vol.=Volume, Last=Premium) Australian Dollar 79.92 =>(St=.7992 USD/AUD) 50,000 Australian Dollars-cents per unit. =>(AUD 50,000=Size, prices in 78 June 9 3.37 20 1.49 USD cents) 79 April 20 1.79 16 0.88 80 May 15 1.96 8 2.05 80 June 11 2.29 9 2.52 82 June 1 1.38 2 3.61 ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ X=Srike T=Maturity Call Premium Put Premium Price Example: Payable AUD 100M in Mid-June St= .7992 USD/AUD Xcall-June = .78 USD/AUD, P = USD .0337 Xput-June = .78 USD/AUD, P = USD .0149 Xcall-June = .80 USD/AUD. P = USD .0229 Xput-June = .80 USD/AUD. P = USD .0252 Xcall-June = .82 USD/AUD, P = USD .0138 Xput-June = .82 USD/AUD. P = USD .0361 1. Out-of-the-money: Xcall-June = 0.82 USD/AUD (or Xcall-June = .80 USD/AUD, almost ATM) Xcall-June = 0.82 USD/AUD, Premium = USD .0138 Cost = Total premium = AUD 100M * USD .0138/AUD = USD 1.38M Cap = AUD 100M x 0.82 USD/AUD = USD 82M (Net cap = USD 83.38M) Xcall-June = 0.80 USD/AUD, Premium = USD .0229 (almost ATM) Cost = Total premium = AUD 100M * USD .0229/AUD = USD 2.29M Cap = AUD 100M x 0.82 USD/AUD = USD 80M (Net cap = USD 82.29M) 2. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

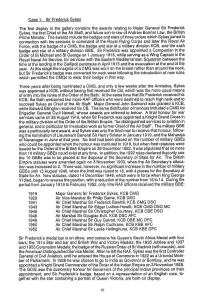

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Ooking Back At·Laker Task Force II Moving On

VOLUME 45 NUMBER 6 MARCH 15, 1982 The Latest Headline News! Award of Task Force II_ Excellence MoVing On President Ed Meyer and top com !. pany officials will honor 119 em With its first task behind it- selection of ployees at TWA's annual Award of. the bumping priority system favored by Excellence dinner in New York on most passenger ·service employees. -, April2. The reception will be he)~ at TWA's newly instituted Task Force pro Hilton International's Vista Interna gram is moving on to tackle its next_chore. tional Hotel in the World Trade Five members of the original task force Center. Roster of those selected for served as a transition team to prepare the outstanding individual performance way for the program's continuation. On during 1981 is on page 8. February 24, they met in New York to take the first step in selection of Task Force II's · membership and agree on the area of -.ooking Back concern it will cover. Members of the transition group were · Richard Ebright, customer service agent At·Laker in-charge, CMH; Deborah Irons, reserva Travel Weekly points out that the passing tions agent, S TL; Sandy Torre, from the scene of Laker Airways was reservations agent, LAX; and Jerry Stanhi- . accompanied by a lot of nonsense in the bel, customer service agent, JFK. media perpetrating "myths" about that Their first order of business was to pick operation. locations at random in each of the three One was The New York Times' assertion TWA regions; passenger· service em that "Laker accounted for 25% of all air ployees at those locations will choose, traffic between Britain and America" -a from among those who have volunteered to gross exaggeration, by a factor of five or serve, the representatives who will make so. -

N. 11-12/2017 1 Incidente Aereo a Terracina

PERIODICO DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE NAZIONALE UFFICIALI AERONAUTICA (ANUA) FONDATO NEL 1953 DA LUIGI TOZZI Direzione-Redazione-Amministrazione: 00192 Roma - Via Marcantonio Colonna, 25 - Tel. 0632111740 Verso il 2018 con visione serena degli impegni a m o R che dobbiamo affrontare B C D , 1 a m m o c , 1 . t r a ) 6 4 . n 4 0 0 2 / 2 0 / 7 2 . L n i . v n o c ( 3 0 0 2 / 3 5 3 . L . D - . t s o p . b b a n i . z i d e p 10-25 Dicembre 2017 S - . A . p . S e n a i l a t I e t s o P - V I X L o n n A Il percorso celebrativo del bimestre sia di stimolo per impegnarci a dare il meglio di noi stessi con altruismo e generosità N. 11-12 /2017 In questo numero: Periodico dell’Associazione Nazionale Ufficiali Aeronautica (ANUA) fondato nel 1953 da Luigi Tozzi N. 11-12 Novembre-Dicembre 2017 Ufficio Presidenza Nazionale Direzione - Redazione - Amministrazione 00192 Roma - Via Marcantonio Colonna, 25 Tel. 0 6 32111740 - Fax 0 6 4450786 E-mail: [email protected] “Il Corriere dell’Aviatore” E-mail: [email protected] Direttore editoriale Mario Majorani Direttore responsabile Mario Tancredi Redazione Giuliano Giannone, Guido Bergomi, Angelo Pagliuca Delegato Amministrazione Vincenzo Gentili Autorizzazione T ribunale di Roma 2546 del 12-2-52 ANU A/Centro Studi Editrice proprietaria Associato all’U.S.P.I. Iscrizione al R.O.C. n. 26014 Impaginazione e Stampa: STILGRAFICA srl 00159 Roma • Via Ignazio Pettinengo, 31/33 Tel. -

Imperial Airways

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 1 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW.XV Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 2 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. G-ADSR, Ensign Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 3 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW15 Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways, air to air, 1932. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 4 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBLF, Imperial Airways, 1929. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 5 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, 1937. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 6 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atlanta, G-ABTL, Astraea Imperial Airways, Royal Mail GR. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 7 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atalanta, G-ABTK, Athena, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 8 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Argosy, G-EBLO, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 9 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 10 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 11 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBOZ, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 12 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW 27 Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 13 AVRO. 652, G-ACRM, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 14 AVRO. 652, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 15 AVRO. Avalon, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 16 BENNETT, D. C. -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

February 2021

DAC - MDC - Boeing Retirees Ron Beeler- Editor (562) 296-8958 of California HEADQUARTERS: P.O. BOX 5482, FULLERTON, CA, 92838, (714) 522-6122 Newsletter No. 199 www.macdacwestretirees.org February 2021 to make this a feature with each issue of the Jim’s Corner ROUNDUP. Hello to all Retiree Association members. I Some of the things to be thankful for as 2020 hope this finds you and your loved ones closed out: that the vaccine for the COVID healthy and safe. Glad to leave 2020 behind virus is at hand, the presidential election is us and am hopeful that 2021 will be much behind us, and the 737MAX finally gets the improved for us, our country, and the world. clearance from the FAA to return to the skies. However, we are certainly not out of the Some of the things I am hopeful for in 2021: woods by any means. Our Luncheon venue, the COVID virus is eradicated, that our The Sycamore Centre, is shut down with no frontline workers get a rest from the heroic planned or anticipated date as to when they job they have done, that our government can will be allowed to hold events. With that said, function in a way that brings all of our we will NOT be having a Luncheon at our divergent ways together and that we see our traditional first Tuesday in March. That said, travel industry, and those that support it, start we do not know when we might have our next an amazing recovery. get together. At the last Board Meeting it was decided that we would still try to hold two In the meantime, please take all the necessary Luncheons in 2021. -

A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians

RAF COLLEGE CRANWELL “The Cranwellian Many” A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians Version 1.0 dated 9 November 2020 IBM Steward 6GE In its electronic form, this document contains underlined, hypertext links to additional material, including alternative source data and archived video/audio clips. [To open these links in a separate browser tab and thus not lose your place in this e-document, press control+click (Windows) or command+click (Apple Mac) on the underlined word or image] Bomber Command - the Cranwellian Contribution RAF Bomber Command was formed in 1936 when the RAF was restructured into four Commands, the other three being Fighter, Coastal and Training Commands. At that time, it was a commonly held view that the “bomber will always get through” and without the assistance of radar, yet to be developed, fighters would have insufficient time to assemble a counter attack against bomber raids. In certain quarters, it was postulated that strategic bombing could determine the outcome of a war. The reality was to prove different as reflected by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris - interviewed here by Air Vice-Marshal Professor Tony Mason - at a tremendous cost to Bomber Command aircrew. Bomber Command suffered nearly 57,000 losses during World War II. Of those, our research suggests that 490 Cranwellians (75 flight cadets and 415 SFTS aircrew) were killed in action on Bomber Command ops; their squadron badges are depicted on the last page of this tribute. The totals are based on a thorough analysis of a Roll of Honour issued in the RAF College Journal of 2006, archived flight cadet and SFTS trainee records, the definitive International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) database and inputs from IBCC historian Dr Robert Owen in “Our Story, Your History”, and the data contained in WR Chorley’s “Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War, Volume 9”. -

Laker Airways: Recognizing the Need for a United States-United Kingdom Antitrust Treaty Mark P

Penn State International Law Review Volume 4 Article 4 Number 1 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1985 Laker Airways: Recognizing the Need for a United States-United Kingdom Antitrust Treaty Mark P. Barbolak Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Barbolak, Mark P. (1985) "Laker Airways: Recognizing the Need for a United States-United Kingdom Antitrust Treaty," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 4: No. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Laker Airways: Recognizing the Need for a United States-United Kingdom Antitrust Treaty Cover Page Footnote The uthora wishes to acknowledge the support of his family who has encouraged him in writing this article and who has also supported him in any endeavor which he has chosen to undertake. This article is available in Penn State International Law Review: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol4/iss1/4 Laker Airways: Recognizing the Need for a United States-United Kingdom Antitrust Treaty Mark P. Barbolak* I. Introduction The United States and the United Kingdom have long been in conflict over the extraterritorial application of United States anti- trust laws. The British resent the often lucrative remedies that United States competition laws provide because they disagree with the philosophy behind those laws.