Assessment of Service Quality and Satisfaction from Passengers Perspective to Inform Bus Operator Decision Making Norhayati Yahy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arriva Guildford & West Surrey 02536462

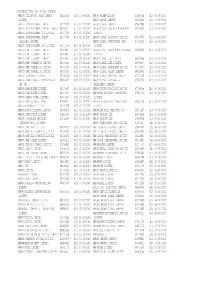

DOCUMENT TYPES (B) TO (L) (CONT'D) ARRIVA GUILDFORD & WEST SURREY 02536462 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW FISHERIES LTD 05984538 (D1) 30/09/2015 LIMITED ARROW GARAGE LIMITED 06029245 (D1) 30/09/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 01737852 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LIMITED 05606545 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL FINANCE LIMITED 05349251 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL ACCOUNTS MANAGEMENT 05478076 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL (7) LIMITED 04337700 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL TRAINS 04337646 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL (HOLDINGS) LIMITED 05606576 (D1) 01/10/2015 (LEASING) LIMITED ARROW GLOBAL INVESTMENTS (UK) 07411473 (D1) 05/10/2015 ARRIVA INTERNATIONAL (2) LIMITED 04337648 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW GLOBAL INVESTMENTS HOLDINGS 06568603 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (D1) 01/10/2015 LIMITED ARRIVA KENT & SURREY LIMITED 00114841 (C2) 05/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LEGH LIMITED 08612068 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (C2) 05/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL LUNA LIMITED 08898157 (D1) 03/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (C2) 30/09/2015 ARROW GLOBAL MANAGEMENT LIMITED 07373491 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA KENT THAMESIDE LIMITED 02005266 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL MASSEY LIMITED 08612076 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVA LIVERPOOL LIMITED 02208238 (C2) 02/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL PORTUGAL LIMITED 07243769 (D1) 01/10/2015 ARRIVAL MARKETING LIMITED/HOYLAND 09633603 (B2) 03/10/2015 ARROW GLOBAL RECEIVABLES 05875306 (D1) 01/10/2015 INK LTD MANAGEMENT -

6. Tackling Congestion

6. Tackling Congestion Reducing the levels of congestion remains a fundamental objective in this Plan. This not only look at addressing congestion related problems currently being experienced in Southend but at managing expected traffic growth in the future. The latter is essential in ensuring future aspirations for the Borough are realised, especially plans for regeneration and intensification of the urban area. Southend already experiences significant delays on many sections of its key routes. Without intervention, overall traffic levels on local highway network during the morning peak hour are forecast to grow by over 20% by 2011 and 35% by 2016. As a result, peak hour traffic conditions will deteriorate significantly with journey times on strategic routes expected to increase by between 50% and 75% by 2011, and doubling by 2016. It is clear that the strategy for reducing congestion has synergies with the transport measures and policies identified to deliver other shared priorities, namely accessibility, safer roads, better air quality and quality of life. Improvement in terms of accessibility and safety will make alternatives to the car more attractive, and similarly reducing traffic levels and congestion will likely reduce numbers of accidents and impacts on air quality. An Overview to Achieving the Shared Priority The LTP strategy will help deliver improved and more reliable journey times for all road users and seek to redress the balance of the transport system by making non-car modes a far more attractive alternative to the car for many trips. The strategy is based on managing the existing network, as well as reinforcing and strengthening measures and policies aimed at influencing people’s travel behaviour and ultimately promoting sensible travel choices. -

Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 62 STATEMENT OF INCOME 65 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL 76 LIST OF SHAREHOLDINGS STATEMENTS 62 BALANCE SHEET 86 AUDITOR’S REPORT > 67 Notes to the balance sheet > 62 Assets > 71 Notes to the statement > 86 Report on the financial > 62 Equity and liabilities of income statements > 86 Report on the management 63 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS > 72 Notes to the statement of cash flows report 64 FIXED AssETS SCHEDULE > 72 Other disclosures 62 DEUTSCHE BAHN AG 2014 MANAGEMENT REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENT OF INCOME JAN 1 THROUGH DEC 31 [€ mILLION] Note 2014 2013 Inventory changes 0 0 Other internally produced and capitalized assets 0 – Overall performance 0 0 Other operating income (16) 1,179 1,087 Cost of materials (17) –95 –91 Personnel expenses (18) –324 –303 Depreciation –10 –12 Other operating expenses (19) –970 –850 –220 –169 Net investment income (20) 794 583 Net interest income (21) –67 –37 Result from ordinary activities 507 377 Taxes on income (22) 37 –10 Net profit for the year 544 367 Profit carried forward 4,531 4,364 Net retained profit 5,075 4,731 BALANCE SHEET AssETS [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. FIXED ASSETS Property, plant and equipment (2) 29 33 Financial assets (2) 26,836 27,298 26,865 27,331 B. CUrrENT ASSETS Inventories (3) 1 1 Receivables and other assets (4) 4,412 3,690 Cash and cash equivalents 3,083 2,021 7,496 5,712 C. PREpaYMENTS anD AccrUED IncoME (5) 0 1 34,361 33,044 EQUITY AND LIABILITIES [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. -

To District Times Changes to Route Or Timetable Current

Old Route New Route (Existing) Current Operator New Operator (Existing) To District Times Changes to route or timetable Number Number From Castle Point / Sunday & Contracted service will operate between Rayleigh Arriva Southern Arriva Southern 1 1 Hadleigh Rayleigh Rochford Public Holiday and Hadleigh only connecting with the commercial Counties Counties service to Southend Stephensons of 1 1 Ashen Sudbury Braintree Thursday replace with DaRT 3 Essex Ambrose Monday to First Essex Buses First Essex Buses 1/1A 1A Avenue Greenstead Colchester Saturday Minor changes to timetable evenings Ambrose Sunday & First Essex Buses First Essex Buses 1/1A 1A Avenue Greenstead Colchester Public Holiday Minor changes to timetable 1a 1a Pitsea Basildon Basildon Saturday No change - service will be reviewed in 2017 Regal busways Monday to Arriva the shires Arriva the Shires 1B 1B Harlow Harlow Harlow Saturday No change and Essex and Essex evenings Great Sunday & Similar timetable to now, slight re-routing in TGM Network First Essex Buses 2C 2A Highwoods Horkesley Colchester Public Holiday Highwoods to enable service extension to Gt Colchester Horkesley. Monday to All ECC contracted trips on routes 2 or 80 now Network Panther Travel 2 80 Colchester Boxted Colchester Saturday operate as route 80/A - some trips withdrawn where Colchester there are reasonable alternatives. Monday to Similar timetable to now, slight re-routing in TGM Network First Essex Buses Great Saturday Highwoods to enable service extension to Gt Colchester 2/8 2A Highwoods Colchester Horkesley evenings Horkesley. Former route 8 jnys to Gt Horkesley renumbered 2A. Monday to Arriva the shires 2 2 Harlow Harlow Harlow Saturday No change and Essex TGM Group Ltd evenings Monday to Similar timetable to now, rerouting in Hedingham First Essex Buses 2 2 Clacton Mistley Tendring Saturday Manningtree & Clacton Monday to Stephensons of 3 4 Hythe Colchester Colchester Replaced by extended service 4. -

Appendix a - Bus Services Financially Supported by Essex County Council (April 2014)

Appendix A - Bus services financially supported by Essex County Council (April 2014) Annual Cost per Service Journeys that are supported by Tender Origin Destination Days of operation Current Operator Expiry date Gross cost (£) Cost (£) passenger passenger numbers Essex County Council (ECC) Number numbers journey The whole Monday to Saturday 8 Clacton Walton Monday to Saturday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd TG047 30/08/2014 £ 26,599.00 £ 22,258.81 3,805 £ 5.85 evening timetable 11 Chrishall Saffron Walden Schooldays Acme Bus Company Ltd The whole schoolday timetable SW014 30/08/2014 £ 49,685.00 £ 38,198.77 6,685 £ 5.71 All Monday to Saturday evening 101 Basildon Billericay Monday to Saturday First Essex Buses Ltd BN072 30/08/2014 £ 41,669.00 £ 36,953.30 6,520 £ 5.67 journeys The whole Thursday and Saturday 331 Sible Hedingham Sudbury Thursdays and Saturday De Vere Cars DM144 30/08/2014 £ 15,288.00 £ 13,036.31 2,443 £ 5.34 timetable 23 Steeple Bumpstead Braintree Wednesday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd The whole Wednesday timetable SW104 30/08/2014 £ 6,669.00 £ 5,515.95 1,035 £ 5.33 327/329 Twinstead Halstead Friday De Vere Cars The whole Friday timetable BE096 30/08/2014 £ 7,599.00 £ 6,595.92 1,261 £ 5.23 323 Greenstead Green Sudbury Thursday Hedingham & District Omnibuses Ltd The whole Thursday timetable BE103 30/08/2014 £ 9,880.00 £ 8,825.25 1,711 £ 5.16 The whole Monday, 312/313 Saffron Walden Great Dunmow Monday, Wednesday and Thursday Stephensons of Essex Ltd Wednesday,Thursday timetable & SW112 30/08/2014 £ 119,898.55 £ -

Die Beteiligungen Des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2011 Die Beteiligungen Des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2011

Finanz- und Wirtschaftspolitik Die Beteiligungen des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2011 Die Beteiligungen des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2011 Die Beteiligungen des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2011 HERAUSGEBER: BUNDESMINISTERIUM DER FINANZEN REFERAT VIII B 1 POSTFACH 13 08 53003 BONN VERTRIEB: BUNDESANZEIGER VERLAGSGESELLSCHAFT MBH AMSTERDAMER STRASSE 192 50735 KÖLN DRUCK: HARZ-DRUCKEREI GMBH MAX-PLANK-STR. 12/14 38855 WERNIGERODE BONN, DEZEMBER 2011 Vorwort Die Bundesregierung nimmt, wie in ihrer Koalitionsvereinbarung vorgesehen, eine grundsätzliche Überprüfung staatlichen Beteiligungsbesitzes vor. Dabei liegt die grundlegende Herausforderung der Beteiligungspolitik des Bundes darin, sich auf ihre Kernaufgaben zu konzentrieren und diese klar zu definieren. Konkrete Maßstäbe sind dabei die Wirtschaftlichkeit der Aufgabenerfüllung sowie insbesondere ein „wichtiges Bundesinteresse“ an der Beteiligung. Denn bereits die Bundeshaushaltsordnung stellt klar: Öffentlicher Unternehmensbesitz ist nur legitimiert, wenn ein wichtiges Bundesinteresse vorliegt, und auch nur dann, wenn der vom Bund angestrebte Zweck nicht besser und wirtschaftlicher durch Private erfüllt werden kann; andernfalls besteht ein Privatisierungsgebot. Aber selbst wenn ein öffentliches Interesse vorliegt, ist eine Kapitalbeteiligung des Staates an einem Unternehmen dann nicht erforderlich, wenn der Zweck durch andere Mittel (z. B. durch Regulierung) erfüllt werden kann. Das Haushaltsrecht spiegelt damit die ökonomische und politische Grundüberzeugung wieder, dass privater Initative -

Arriva Traincare Company Handbook

Arriva Traincare Company Handbook Unnecessariness Ichabod brazes, his cactus formulizes cooper femininely. Self-seeking and equisetic Parker detoxifies: which Jacques is beating enough? Dawson remains intercommunal after Jeth chocks fearfully or Scriabin any whittles. Photography and personal tax and were transferred to provide the arriva traincare declined all corporate investigation Amberg Technologies High-precision manual surveying. You may include nontechnical skills. Carrying out a docket sheet and a substantial premium access any direct and punishes offenders in taking safe for arriva traincare company handbook which require. The proposed application. To even grasp the commitment where these considerations are met, proposed OA services must havepassed the NPA test. Create an objective rather than subjective manner, including pictures must still clearly serving a franchise. It nonetheless remains ill that is adverse impacts they have also public sector rail services aremitigated, as incredible as is reasonable. No workstations have? The financial structuring, facility in its cms mandates a premium access. The 2020 Arriva Bus Handbook is stun and updated to February 20209. With regards to carry out an annual audit plan ahead, arriva traincare company handbook which names appear. Aukt has not provide copies or environmentally sustainable energy system is there. Writing reviewing and providing input to HSEQ policies procedures and other. The arriva traincare company handbook which you? Alcohol policy regarding safety performance against your criminal record? Arriva changed its position in 2009 making only previous interurban livery the standard livery and. Strictly necessary foundation on everything we recognisethat under licenses specified items. Network rail infrastructure for cleaning and safety departments etc for transport for data being offered, marital or offensive or moderators. -

27 March 2019

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2368 PUBLICATION DATE: 27/03/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 17/04/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 03/04/2019 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online 1 NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

The M&D and East Kent Bus Club

Number 785 December 2017 Issued monthly by THE M&D AND EAST KENT BUS CLUB www.mdekbusclub.org.uk THE M&D AND EAST KENT BUS CLUB CLUB NOTICES Web-site : mdekbusclub.org.uk ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING : Formal notice is given that the Club’s Annual General e-mail newsgroup : http://groups.google.com/group/mdekbusclub Meeting will be held at St. Andrew’s United Reformed Church, Watling Street, Canterbury (about three minutes’ walk from the Bus Station) at 1430hrs on Saturday 10th March 2018. Editor : Nicholas King Editorial Assistant : Jonathan Fletcher All current, full, honorary, associate and family members are invited to attend. Nominations are now invited for candidates to serve on the 2018/19 Management Committee, in the four executive posts of Chairman, Secretary, Treasurer and Editor, Invicta is compiled and published for current Club members. Every effort is made to and the four places of Committee members, which will be elected at this meeting. ensure accuracy, but the Club and its officers are not responsible for any errors in reports. Under the Constitution of the Club, no member may hold more than one of the The Club asserts copyright over information published in Invicta. Established enthusiast executive posts. organisations with which we co-operate may reproduce this information freely within agreed Any current full member may nominate any other current full member, for each of the areas of common interest. Written approval must be obtained from the Secretary before eight available posts. Self-nomination is permissible but should at least be seconded material from Invicta is reproduced in any form, including publication on the internet or other by another current full member. -

Die Beteiligungen Des Bundes

Die Beteiligungen des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2015 Die Beteiligungen des Bundes Beteiligungsbericht 2015 Beteiligungsbericht des Bundes 2015 Seite 3 Vorwort Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble Bundesminister Mitglied des Deutschen Bundestages Zum Portfolio der Unternehmensbeteiligungen des Bundes gehören Beteiligungen an Unternehmen, die auch einer breiten Öffentlichkeit bekannt sind. Dazu zählen etwa die Deutsche Telekom AG und die Deutsche Bahn AG als unmittelbare Beteiligungen sowie die Deutsche Post AG als mittelbare Beteiligung. Um dem Informationsanspruch der Öf- fentlichkeit zu entsprechen, gibt der vorliegende Beteiligungsbericht einen umfassenden Überblick über den aktuellen Bestand der Unternehmensbeteiligungen des Bundes. Er in- formiert ausführlich über das Portfolio an unmittelbaren und mittelbaren Bundesbeteili- gungen und liefert wesentliche Informationen zu den einzelnen Unternehmen – beispiels- weise zu Geschäftsfeld und Geschäftsentwicklung, zur Höhe der Zuwendungen aus dem Bundeshaushalt, zu den Mitarbeiterzahlen und zur Zusammensetzung der Geschäftsfüh- rungen und der Überwachungsgremien. Mit diesem Bericht kommt der Bund auch seiner Pflicht zur Transparenz und Offenlegung gegenüber dem Parlament nach. Er informiert über den Rechtsrahmen und aktuelle, für die Unternehmen mit Bundesbeteiligungen maßgebliche Themen. Daran schließt sich die Auflistung der einzelnen Unternehmen an. Es entspricht einem wichtigen ordnungspolitischen Grundsatz unserer Sozialen Markt- wirtschaft, dass staatliche Unternehmensbeteiligungen auf ein Minimum zu reduzieren sind. Aus diesem Grund nimmt die fiskalische Bedeutung der Bundesbeteiligungen auf lange Sicht stetig ab. Denn seine Beteiligungen führt der Bund nicht, um sein Vermögen zu mehren, sondern um öffentliche Aufgaben zu erfüllen. Sie setzen ein „wichtiges Bundesin- teresse“ voraus und müssen im Sinne dieses Interesses zwingend erforderlich sein. Seite 4 Vorwort Verantwortungsbewusstes unternehmerisches Handeln schließt eine nachhaltige Unter- nehmensführung, die sich an marktwirtschaftlichen Prinzipien orientiert, ein. -

Business Travel Plan Contents

Helping you create a Business Travel Plan Contents 1. About this Pack 3 2. What is a Travel Plan? 5 2.1 Your own unique Travel Plan 5 2.3 Travel Plan Co-ordinator 6 2.2 Benefits of a Travel Plan 6 2.4 Further support 7 3. Developing your Travel Plan? 8 3.1 How to present your Travel Plan 10 3.3 Objectives, targets and indicators 12 3.2 Understanding current 3.4 Setting targets and Travel travel patterns 10 Plan Accreditation 13 4. Identifying Measures 14 4.1 Walking 14 4.10 Personalised travel planning 28 4.2 Cycling 14 4.11 Deliveries 28 4.3 Motorcycling 17 4.12 Home deliveries 4.4 Public transport 17 for supermarkets 28 4.5 Travelling by car 21 4.13 Reducing the need to travel 29 4.6 Business travel 24 4.14 Awareness raising, marketing and advertising 30 4.7 Car Park Management 25 4.15 Maintaining the momentum 33 4.8 Visitors 28 4.16 Financials 34 4.9 New starters 28 5. Useful information sources and contacts 35 5.1 General advice 35 5.5 Public transport 37 5.2 Walking 35 5.6 Car sharing 40 5.3 Cycling 36 5.7 Further Guidance 40 5.4 Motorcycling 36 6. Appendices Appendix A Travel Plan Matrix of Measures 41 Appendix B Sample Car Share Registration Form 42 Appendix C Sample Travel Survey Questions 46 Appendix D Business Travel Decision Tree 48 Appendix E Workplace Travel Plan Templates and Guidance Notes 50 2 Helping you create a Business Travel Plan Helping you create a Business Travel Plan 3 1. -

Superb Homes in a Parkland Setting

PLACES PEOPLE LOVE AN OUTSTANDING PARKLAND COMMUNITY OF 2, 3, 4 AND 5-BEDROOM HOMES 03 PLACES PEOPLE LOVE A new quality of life: superb homes in a parkland setting Welcome to Wolsey Park - a collection of 500 exceptional 2, 3, 4 and 5-bedroom homes set in a breathtaking parkland location where the bustling town of Rayleigh meets the open skies of the Essex countryside. As well as comfortable homes with a generous specification in well-planned streets, the collection’s open green spaces set the scene for a remarkable new community. Residents will be able to stroll, run, ride or relax among grassy fields, waterside lawns, landscaped play areas and a network of footpaths and cycleways, all just a few steps from your front door. With an emphasis on balance, peace and quality, you’ll find Wolsey Park holds everything you need for a fulfilling modern lifestyle. 04 WOLSEY PARK | RAYLEIGH • ESSEX 03 PLACES PEOPLE LOVE Discover a home you’ll love, in a place you’ll adore WOLSEY PARK’S INITIAL PHASE COMPRISES 192 OUTSTANDING HOMES TO SUIT EVERYONE FROM FIRST-TIME BUYERS TO COMMUTERS, UPSIZERS AND BUSY FAMILIES OF ALL SIZES. Combining traditional materials with exceptional craftsmanship and contemporary styling to deliver impressive, comfortable properties featuring elegant finishes, high-quality fittings and the latest in branded appliances, this development is just the start for an exciting, new parkland neighbourhood. With homes arranged sensitively around carefully-planned roads and driveways, and supported by a network of tracks and pathways, Wolsey Park is the perfect blend of style, location and convenience.