Information As a Product: Not Goods, Not Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Divergence the Princeton Economic History

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD Joel Mokyr, Editor Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815, by Philip T. Hoffman The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914, by Timothy W. Guinnane Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory, by Cormac k Gráda The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, by Kenneth Pomeranz THE GREAT DIVERGENCE CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY Kenneth Pomeranz PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2000 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA POMERANZ, KENNETH THE GREAT DIVERGENCE : CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY / KENNETH POMERANZ. P. CM. — (THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD) INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00543-5 (CL : ALK. PAPER) 1. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—18TH CENTURY. 2. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—19TH CENTURY. 3. CHINA— ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—1644–1912. 4. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT—HISTORY. 5. COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS. I. TITLE. II. SERIES. HC240.P5965 2000 337—DC21 99-27681 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN TIMES ROMAN THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (PERMANENCE OF PAPER) WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3579108642 Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

The First Great Divergence

Mellon-Sawyer Seminar 2007/8 “The first great divergence: China and Europe, 500-800 CE” Organized by Ian Morris, Walter Scheidel, and Mark Lewis, Departments of Classics and History, Stanford University Sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Six hundred years ago China was the most powerful state on earth. The eunuch admiral Zheng He spent 1406 cruising around the Indian Ocean at the head of 30,000 crew in a fleet of giant Chinese “treasure ships,” trading, collecting tribute, and setting up and deposing client kings at will. By 1433, Chinese ships were visiting Arabia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, and probably Australia too. By any reasonable estimate, China seemed set to become the world’s first global power. But that did not happen. Anti-trade Confucian factions won out in struggles at the Ming court, and long-distance voyages were banned. By 1467, most records of Zheng’s voyages were lost or destroyed. Half a millennium later, far from dominating as the world, China seemed – at least to western observers – to be going backward. When a dispute over opium trading escalated uncontrollably in 1839, the British sent a small naval force to claim damages from the governor of Canton. A single ironclad gunboat blasted its way through all the Chinese defenses, and in 1842, with the Grand Canal under British control, Nanjing facing plunder, and famine closing in on Beijing, China conceded British demands for open ports and the right to send missionaries deep into the country. This defeat triggered crises that brought China to the verge of partition. One Hong Xiuquan, a failed civil service candidate who developed his own bizarre version of Christianity out of the teachings of the missionaries at Canton, led the massive Taiping Rebellion to install a Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. -

The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 34, Number 2—Spring 2020—Pages 192–214 The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure Shane Greenstein his internet barely existed in a commercial sense 25 years ago. In the mid- 1990s, when the data packets travelled to users over dial-up, the main internet T traffic consisted of email, file transfer, and a few web applications. For such content, users typically could tolerate delays. Of course, the internet today is a vast and interconnected system of software applications and computing devices, which society uses to exchange information and services to support business, shopping, and leisure. Not only does data traffic for streaming, video, and gaming applications comprise the majority of traffic for internet service providers and reach users primarily through broadband lines, but typically those users would not tolerate delays in these applica- tions (for usage statistics, see Nevo, Turner, and Williams 2016; McManus et al. 2018; Huston 2017). In recent years, the rise of smartphones and Wi-Fi access has supported growth of an enormous range of new businesses in the “sharing economy” (like, Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb), in mobile information services (like, social media, ticketing, and messaging), and in many other applications. More than 80 percent of US households own at least one smartphone, rising from virtually zero in 2007 (available at the Pew Research Center 2019 Mobile Fact Sheet). More than 86 percent of homes with access to broadband internet employ some form of Wi-Fi for accessing applications (Internet and Television Association 2018). It seems likely that standard procedures for GDP accounting underestimate the output of the internet, including the output affiliated with “free” goods and the restructuring of economic activity wrought by changes in the composition of firms who use advertising (for discussion, see Nakamura, Samuels, and Soloveichik ■ Shane Greenstein is the Martin Marshall Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts. -

MARKETING PLAN OUTLINE (Recommended Length: 3-5 Pages)

MARKETING PLAN OUTLINE (Recommended Length: 3-5 pages) 1. Company Name 2. Marketing or Promotional Statement 5-7 words briefly describing your business and its product or service 3. Product or Service Description Nature and detailed description of your product or service What do you sell? What are the benefits your products/services? What is special, unique, or different about your product or service? Describe your Unique Selling Proposition (USP). 4. Market Analysis Service/Industry Background and Description Market Segments Current Market Situation Analysis Competitive Analysis - Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats Marketing Research Who are your competitors? What do your competitors do better than you? What do you do better than your competitors? What is your competitive position? How large is your overall market? What is your market share? Is your market share increasing, shrinking, or stable? How do your prices compare to your competitors' prices? How do you establish prices? What are your business strengths? What are your business weaknesses? What might keep you from achieving your goals? Is your market changing in any ways? What facts or new information do you need to figure out? 5. Target Market Target Market Definition Demographic and Psychographic Profile for Primary and Secondary Customers What are your target markets? Who are your current customers? What are their buying habits? Why do your customers actually buy your goods/services? Who are your best customers and prospects? Marketing Plan Outline (Continued) 6. Marketing Objectives Revenues (Year one, Year two, Year three) Profits (Year one, Year two, Year three) Market Share – Optional What are your overall goals? 7. -

The Paradigms of Industry 4.0 and Circular Economy As Enabling

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The Paradigms of Industry 4.0 and Circular Economy as Enabling Drivers for the Competitiveness of Businesses and Territories: The Case of an Italian Ceramic Tiles Manufacturing Company Fernando E. Garcia-Muiña 1 , Rocío González-Sánchez 1 , Anna Maria Ferrari 2 and Davide Settembre-Blundo 1,3,* 1 Department of Business Administration (ADO), Applied Economics II and Fundaments of Economic Analysis, Rey-Juan-Carlos University, 28032 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (F.E.G.-M.); [email protected] (R.G.-S.) 2 Department of Sciences and Methods for Engineering, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, 42122 Reggio Emilia, Italy; [email protected] 3 Gruppo Ceramiche Gresmalt, Via Mosca 4, 41049 Sassuolo, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0536-867-011 Received: 1 November 2018; Accepted: 30 November 2018; Published: 4 December 2018 Abstract: Sustainable development and the circular economy are two important issues for the future and the competitiveness of businesses. The programs for the integration of sustainability into industrial activities include the reconfiguration of production processes with a view to reducing their impact on the natural system, the development of new eco-sustainable products and the redesign of the business model. This paradigm shift requires the participation and commitment of different stakeholder groups and industry can completely redesign supply chains, aiming at resource efficiency and circularity. Developments in key ICT technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), help this systemic transition. This paper explores the phases of the transition from a linear to a circular economy and proposes a procedure for introducing the principles of sustainability (environmental, economic and social) in a manufacturing environment, through the design of a new Circular Business Model (CBM). -

Next Generation Supply Chain: Supply Chain 2020

Supply Chain 2020 Next generation supply chain: Supply chain 2020 July 2013 Copyright © 2013, by McKinsey & Company, Inc. Next generation supply chain: Supply chain 2020 Knut Alicke Balaji Iyer 2 Next generation supply chain Supply chain 2020 3 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Introduction 7 1. Key trends shaping supply chains 9 2. Implications for the next generation supply chain 15 4 Next generation supply chain Supply chain 2020 5 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Sumit Dutta, a partner in our Mumbai office, and Muthiah Venkateswaran, an associate partner in our Chennai office, for their contributions to this whitepaper. We would like to thank Insa Mareen Wente, a consultant based in our Hamburg office; Kerstin Kubik, a knowledge expert based in our Vienna office; and Markus Leopoldseder, a director of knowledge (supply chain management) based in our Vienna office, for their contributions. We would also like to thank Vineeta Rai for the editorial support; Kulsum Merchant for the support in external relations; J Sathya Kumar and Nipun Gosain for their visual aids support. This whitepaper is not based on any primary research that we conducted; it synthesises our perspectives gained from past research and experience in serving multiple stakeholders of supply chains over many years. For the experience and perspectives, we acknowledge our supply chain practice without whose efforts this whitepaper could not have been published. Finally, we would like to thank the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and CII Institute of Logistics for the opportunity and the forum to provide our perspective on supply chain evolution. This work is independent and has not been commissioned or sponsored in any way by any business, government or other institution. -

Employment Situation of Veterans — 2020

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, March 18, 2021 USDL-21-0438 Technical information: (202) 691-6378 • [email protected] • www.bls.gov/cps Media contact: (202) 691-5902 • [email protected] EMPLOYMENT SITUATION OF VETERANS — 2020 The unemployment rate for veterans who served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces at any time since September 2001—a group referred to as Gulf War-era II veterans—rose to 7.3 percent in 2020, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The jobless rate for all veterans increased to 6.5 percent in 2020. These increases reflect the effect of the coronavirus (COVID- 19) pandemic on the labor market. In August 2020, 40 percent of Gulf War-era II veterans had a service-connected disability, compared with 26 percent of all veterans. This information was obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that provides data on employment, unemployment, and persons not in the labor force in the United States. Data about veterans are collected monthly in the CPS; these monthly data are the source of the 2020 annual averages presented in this news release. In August 2020, a supplement to the CPS collected additional information about veterans on topics such as service-connected disability and veterans' current or past Reserve or National Guard membership. Information from the supplement is also presented in this news release. The supplement was co-sponsored by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Labor's Veterans' Employment and Training Service. -

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

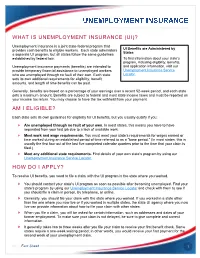

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

A Glossary of Fiscal Terms & Acronyms

AUGUST7,1998VOLUME13,NO .VII A Publication of the House Fiscal Analysis Department on Government Finance Issues A GLOSSARY OF FISCAL TERMS & ACRONYMS 1998 Revised Edition Abstract. This issue of Money Matters is a resource document containing terms and acronyms commonly used by and in legislative fiscal committees and in the discussion of state budget and tax issues. The first section contains terms and abbreviations used in all fiscal committees and divisions. The remaining sections contain terms for particular budget categories and accounts, organized according to fiscal subject areas. This edition has new sections containing economic development, family and early childhood, and housing terms and acronyms. The other sections are revised and updated to reflect changes in terminology, particularly the human services section. For further information, contact the Chief Fiscal Analyst or the fiscal analyst assigned to the respective House fiscal committee or division. A directory of House Fiscal Analysis Department personnel and their committee/division assignments for the 1998 legislative session appears on the next page. Originally issued January 1997 Revised August 1998 House Fiscal Analysis Department Staff Assignments — 1998 Session Committee/Division Fiscal Analyst Telephone Room Chief Fiscal Analyst Bill Marx 296-7176 373 Capital Investment John Walz 296-8236 376 EDIT— Economic Development Finance CJ Eisenbarth Hager 296-5813 428 EDIT— Housing Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Environment & Natural Resources Finance Jim Reinholdz 296-4119 370 Education — Higher Education Finance Doug Berg 296-5346 372 K-12 Education Finance Greg Crowe 296-7165 378 Family & Early Childhood Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Health & Human Services Finance Joe Flores 296-5483 385 Judiciary Finance Gary Karger 296-4181 383 State Government Finance Helen Roberts 296-4117 374 Transportation Finance John Walz 296-8236 376 Taxes — Income, sales, misc. -

Product Development in the World Auto Industry

KIM B. CLARK Harvard University W. BRUCE CHEW Harvard University TAKAHIRO FUJIMOTO Harvard University Product Development in the World Auto Industry CHANGES in international competition in the past decade, and particularly the competitive problems of once-dominant U.S. firms and industries, have heightened interest in what causes international differences in productivity and product quality. Although analysis of macroeconomic data has produced some important insights, recent research has focused increasingly on the comparative behavior of industries, firms, and factories. 1 Such research raises in a direct way the issue of management efficiency. Especially at the factory level, a growing body of evidence Thisresearch was supportedby the Divisionof Research,Graduate School of Business Administration,Harvard University. We are indebted to BrandtGoldstein and Frank Dubinskasfor theirassistance. 1. For an eclectic survey of microeconomicproductivity research see RichardR. Nelson, "Researchon ProductivityGrowth and Productivity Differences: Dead Ends and New Departures,"Journal of EconomicLiterature, vol. 19 (September1981), pp. 1029- 64. Recent exampleswould includeRobert H. Hayes and Kim B. Clark,"Exploring the Sources of ProductivityDifferences at the Factory Level," in Kim B. Clark,Robert H. Hayes, and Christopher Lorenz, eds., The Uneasy Alliance: Managing the Productivity- TechnologyDilemma (Harvard Business School Press, 1985),pp. 151-88;Bernard Eugene Ichniowski, "How Do Labor Relations Matter? A Study of Productivityin Eleven ManufacturingPlants" (Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,1983); and BenjaminKlotz, Rey Madoo, and Reed Hansen, "A Study of High and Low 'Labor Productivity'Establishments in U.S. Manufacturing,"in JohnW. Kendrickand Beatrice N. Vaccara, New Developments in Productivity Measurement and Analysis (University of ChicagoPress for the NationalBureau of EconomicResearch, 1980),pp. -

Automotive Product Design & Development Delphi

AUTOMOTIVE PRODUCT DESIGN & DEVELOPMENT DELPHI by MANUFACTURING, ENGINEERING, AND TECHNOLOGY GROUP CENTER FOR AUTOMOTIVE RESEARCH MARCH 2005 Sponsored by Parametric Technologies Corporation The statements, findings, and conclusions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the project sponsor. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people from many organizations participated in this study and whose contributions are herewith acknowledged. First, the people at PTC without whose financial and intellectual support this study would never have been conducted. Second, a thank you to the people of CAR, specifically Chris Gulis, who analyzed the data, and Dr. David Cole, Brett Smith, and Wendy Barhydt, who edited the report and provided insight into the many conclusions that were drawn from the study. Lastly, we all owe a debt of gratitude to the members of the panel, who donated their time and thoughts to a topic they believed to be one of the most important in the industry today. Richard J. Gerth, Ph.D. Center for Automotive Research 1 GLOSSARY N.A. North American (United States, Canada, Mexico). Off-Shore All other countries not in N.A. PD&D Produce Design and Development. Product Specific Characteristics Main or major characteristics that define the product. For example, the major characteristics for car bodies are the surface finish, gaps, flush, and crash performance. Some major characteristics for engines are horsepower, torque, and fuel efficiency. 2 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................1 -

The Marketing Plan

The Marketing Plan The most important part of a business plan is the Marketing Plan. To keep one’s business on course this plan must be geared toward the business’s mission—its product and service lines, its markets, its financial situation and marketing/sales tactics. ♦ The business must be aware of its strengths and weaknesses through internal and external analysis and look for market opportunities. ♦ The business must analyze its products and services from the viewpoint of the customer—outside-in thinking. What is the customer looking for and what does the customer want (benefits)? The business must gain knowledge of the marketplace from its customers. ♦ The business must analyze its target markets. What other additional markets can the business tap into and are there additional products or services the business can add? ♦ The business must know its competition, current and potential. By identifying the competitor’s strengths and weaknesses the business can improve its position in the marketplace. ♦ The business must make decisions on how to apply its resources to the target market(s). ♦ The business must utilize the information it has gathered about itself, its customers, its markets, and its competition by developing a written Marketing Plan that provides measurable goals. The business must select marketing/sales tactics that will allow it to achieve or surpass its goals. ♦ The business must implement the plan (within an established budget) and then measure its success in terms of whether or not the goals were met (or the extent to which they were). The Marketing Plan is an ongoing tool designed to help the business compete in the market for customers.