Canada's Multi-Jurisdictional COVID-19 Public Health Response – January to May 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

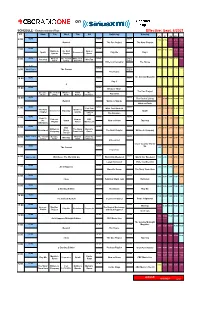

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Global Media Journal German Edition From the field An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation Andrej Školkay1 Abstract: This is a study of suggested approaches to social media regulation based on an explora- tory methodological approach. Its first aim is to provide an overview of the global and local debates and the main arguments and concerns, and second, to systematise this in order to construct taxon- omies. Despite its methodological limitations, the study provides new insights into this very rele- vant global and local policy debate. We found that there are trends in regulatory policymaking to- wards both innovative and radical approaches but also towards approaches of copying broadcast media regulation to the sphere of social media. In contrast, traditional self- and co-regulatory ap- proaches seem to have been, by and large, abandoned as the preferred regulatory approaches. The study discusses these regulatory approaches as presented in global and selected local, mostly Euro- pean and US discourses in three analytical groups based on the intensity of suggested regulatory intervention. Keywords: social media, regulation, hate speech, fake news, EU, USA, media policy, platforms Author information: Dr. Andrej Školkay is director of research at the School of Communication and Media, Bratislava, Slovakia. He has published widely on media and politics, especially on political communication, but also on ethics, media regulation, populism, and media law in Slovakia and abroad. His most recent book is Media Law in Slovakia (Kluwer Publishers, 2016). Dr. Školkay has been a leader of national research teams in the H2020 Projects COMPACT (CSA - 2017-2020), DEMOS (RIA - 2018-2021), FP7 Projects MEDIADEM (2010-2013) and ANTICORRP (2013-2017), as well as Media Plurality Monitor (2015). -

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017 Date Media Outlet Community Header/Lead Type of Coverage Link (if available) Oct 17 Global News at Noon BC-wide TV news story n/a Oct 17 Global News Hours at 6 BC-wide TV news story https://globalnews.ca/video/3810220/global-news-hour- at-6-oct-17-4 (at 21:14 minute mark) Oct 17 MyPrinceGeorgeNow Prince “Drivers Urged to Be Online news https://www.myprincegeorgenow.com/59471/drivers- George Truck Aware” urged-truck-aware/ Oct 17 Today’s Trucking Canada-wide “BC asking drivers to Online news https://m.todaystrucking.com/bc-asking-drivers-to-be- Be Truck Aware” truck-aware Oct 17 CFJC Today Kamloops “Provincial safety Online news http://www.cfjctoday.com/article/592118/provincial- campaign aims to campaign-aims-lessen-road-carnage lessen road carnage” Oct 17 News 1130 Metro “Drivers of smaller Radio News/online http://www.news1130.com/2017/10/17/drivers-smaller- Vancouver cars being warned to news cars-warned-respect-large-commercial-trucks/ respect large trucks” Oct 17 TruckNews.com Canada-wide “B.C. launches Be Online news https://www.trucknews.com/transportation/b-c- Truck Aware launches-truck-aware-campaign/1003081520/ campaign” Oct 17 CKYE RED FM Metro unknown Radio (attended n/a Vancouver the event) Oct 17 97.3 THE EAGLE - CKLR Nanaimo unknown Radio (interviewed n/a Mark Donnelly) Oct 17 Fairchild TV Metro unknown TV news http://www.fairchildtv.com/news.php?n=5c2868adb73b Vancouver 23a26ca29b7244babfdb Oct 17 Kamloopscity.com Kamloops “Drivers urged to -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Wind Inspectors 13 Station 3 : Clic!

Station 31: : WindClic! Inspectors Station 3 : Clic! Résumé Résultats scolaires Les élèves analysent différentes sources de Thème : Mesure et description des conditions données météorologiques (antérieures, actuelles météorologiques (bulletins météorologiques). et prévues) et prennent des décisions à partir Pour obtenir la liste complète des résultats des conclusions de leurs recherches. Pour faire scolaires, veuillez consulter le tableau à la fin du une parenthèse historique, les élèves étudient présent document. comment les conditions météorologiques peuvent avoir contribué à des événements importants de notre époque. Lien avec monde réel • Comment établir et interpréter les bulletins météorologiques (conditions actuelles, prévisions). • Incidence de la météo sur notre vie. • Comment bien se préparer et s'habiller en fonction du temps qu’il fait (notamment l’indice UV ou le refroidissement éolien). • Utiliser la technologie pour échanger des données avec les autres. © Environnement Canada, 2010 Matériel Une élève mesure la vitesse du vent • Ordinateur et accès à Internet • Journal local Préparation Références • Commander le Tableau mural d'observation Indices ultraviolets pour certaines villes canadiennes. météorologique de Météo à l'œil à www.meteo.gc.ca/forecast/textforecast_f. l'Informathèque d'Environnement Canada : html?bulletin=fpcn48.cwao. [email protected] Retrieved December 19, 2008. • Feuille de travail de l'élève, une par élève • Mettez en signets les sites Web suivants dans le CBC News. More hay headed West. www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2002/08/10/hay020810.html navigateur de la classe : Mise à jour : 11 août 2002. (En anglais seulement) Météo à l'œil : www.ec.gc.ca/meteoaloeil-skywatchers/ Environnement Canada. Météo à l'œil. -

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends First Quarter, 2015 Q1 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Q1 research 14 research papers 3 Verbatims 2 Monetary Policy Council releases Q1 policy events 11 policy events and special meetings, including: Montreal Roundtable – Sophie Brochu, President and CEO, Gaz Métro Ottawa Roundtable - Lt. Gen. Charles Bouchard, Country Leader, Lockheed Martin Canada Toronto Roundtable – Mitzie Hunter, Associate Minister of Finance, Ontario Calgary Roundtable – Ian Telfer, Chairman of the Board, Goldcorp Policy Outreach in Q1 109,032 website pageviews 12 policy outreach presentations 34 National Post and Globe and Mail citations Citations in more than 80 media outlets 36 media interviews 20 opinion and editorial pieces 2 Q1 select policy influence Health papers receive national recognition including acknowledgements by senior government officials Nova Scotia’s Health Minister acknowledged the province’s looming fiscal burden while responding to an Institute paper and the Federal Leader of Liberal Party cited the Institute’s recent vaccination study. Reports: Delivering Healthcare to an Aging Population: Nova Scotia’s Fiscal Glacier and A Shot in the Arm: How to Improve Vaccination Policy in Canada Op-Eds: New Brunswick’s demographic challenge: Telegraph- Journal Op-Ed and Booster shot for Ontario’s vaccination policies: Toronto Star Op-Ed Alberta budget is presented on a fully consolidated basis in a format supported by the Auditor General Alberta Finance Minister acknowledged that more clarity is needed in budget presentation after the Institute gave the province a C grade. Report: Credibility on the (Bottom) Line: The Fiscal Accountability of Canada’s Senior Governments, 2013 Op-Eds: A decade of government overspending has left us over-taxed and deeper in debt: Globe and Mail Op- Ed, Saskatchewan budget – Adding up the numbers: Leader-Post Op-Ed Canada and U.S. -

Channel Listing Fibe Tv Current As of June 18, 2015

CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV CURRENT AS OF JUNE 18, 2015. $ 95/MO.1 CTV ...................................................................201 MTV HD ........................................................1573 TSN1 HD .......................................................1400 IN A BUNDLE CTV HD ......................................................... 1201 MUCHMUSIC ..............................................570 TSN RADIO 1050 .......................................977 GOOD FROM 41 CTV NEWS CHANNEL.............................501 MUCHMUSIC HD .................................... 1570 TSN RADIO 1290 WINNIPEG ..............979 A CTV NEWS CHANNEL HD ..................1501 N TSN RADIO 990 MONTREAL ............ 980 ABC - EAST ................................................... 221 CTV TWO ......................................................202 NBC ..................................................................220 TSN3 ........................................................ VARIES ABC HD - EAST ..........................................1221 CTV TWO HD ............................................ 1202 NBC HD ........................................................ 1220 TSN3 HD ................................................ VARIES ABORIGINAL VOICES RADIO ............946 E NTV - ST. JOHN’S ......................................212 TSN4 ........................................................ VARIES AMI-AUDIO ....................................................49 E! .........................................................................621 -

CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers

CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers TIME SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 AM 6:30 CBC Morning 7:00 AM Arthur Magic School Bus 7:30 Rolie, Polie, Olie CBC4 Kids Horrible Histories 8:00:AM CBC4 Kids 8:30 9:00 AM Coronation Franklin Clifford: The Big Red Dog 9:30 Street Scoop & Doozer Get Set For Life CBC4 Kids 10:00 AM Little Bear 10:30 Mr. Dress-up Sesame Park 11:00 AM Riverdale Noddy Theodore Tugboat 11:30 12:00 PM Moving On This Hour Has 22 Minutes 12:30 Man Alive The Red Green Show 1:00 PM OTRA* 1:30 Country Canada North of 60 2:00 PM Sunday CBC 2:30 Encore Road to Avonlea Sports 3:00 PM Best of Canadian Gardener Saturday Current Affairs Coronation Street 3:30 Riverdale 4:00 PM The Nature CBC4 Kids 4:30 of Things 5:00 PM The Wonderful Pelswick The Simpsons 5:30 World of Disney Street Cents JonoVision Basic block program schedule *On the Road Again CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers TIME SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 PM The Saturday Wonderful News: 30 minutes local / 30 minutes national Report 6:30 World of Labatt Disney Saturday Night 7:00 PM Royal Canadian On The Road Again This Hour Has Wind at Air Farce Life & Times Pelswick 22 Minutes 7:30 My Back It's A Living Country Canada Our Hero Just For Laughs 8:00 PM This Hour Has Royal Canada: A 22 Minutes Marketplace Canadian People's the fifth estate CBC Thursday Air Farce Hockey Night 8:30 History Made in Canada Venture / Specials The Red In -

Of Analogue: Access to Cbc/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery

THE END(S) OF ANALOGUE: ACCESS TO CBC/RADIO-CANADA TELEVISION PROGRAMMING IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL DELIVERY by Steven James May Master of Arts, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Applied Arts (Honours), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1999 Bachelor of Administrative Studies (Honours), Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1997 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Steven James May, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The End(s) of Analogue: Access to CBC/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery Steven James May Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University, 2017 This dissertation