The Dying Animal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chrysippus's Dog As a Case Study in Non-Linguistic Cognition

Chrysippus’s Dog as a Case Study in Non-Linguistic Cognition Michael Rescorla Abstract: I critique an ancient argument for the possibility of non-linguistic deductive inference. The argument, attributed to Chrysippus, describes a dog whose behavior supposedly reflects disjunctive syllogistic reasoning. Drawing on contemporary robotics, I urge that we can equally well explain the dog’s behavior by citing probabilistic reasoning over cognitive maps. I then critique various experimentally-based arguments from scientific psychology that echo Chrysippus’s anecdotal presentation. §1. Language and thought Do non-linguistic creatures think? Debate over this question tends to calcify into two extreme doctrines. The first, espoused by Descartes, regards language as necessary for cognition. Modern proponents include Brandom (1994, pp. 145-157), Davidson (1984, pp. 155-170), McDowell (1996), and Sellars (1963, pp. 177-189). Cartesians may grant that ascribing cognitive activity to non-linguistic creatures is instrumentally useful, but they regard such ascriptions as strictly speaking false. The second extreme doctrine, espoused by Gassendi, Hume, and Locke, maintains that linguistic and non-linguistic cognition are fundamentally the same. Modern proponents include Fodor (2003), Peacocke (1997), Stalnaker (1984), and many others. Proponents may grant that non- linguistic creatures entertain a narrower range of thoughts than us, but they deny any principled difference in kind.1 2 An intermediate position holds that non-linguistic creatures display cognitive activity of a fundamentally different kind than human thought. Hobbes and Leibniz favored this intermediate position. Modern advocates include Bermudez (2003), Carruthers (2002, 2004), Dummett (1993, pp. 147-149), Malcolm (1972), and Putnam (1992, pp. 28-30). -

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind Peter Godfrey-Smith The Graduate Center City University of New York Pacific Conservation Biology 19 (2013): 4-9. In thinking about the nature of the mind and its evolutionary history, cephalopods – especially octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid – have a special importance. These animals are an independent experiment in the evolution of large and complex nervous systems – in the biological machinery of the mind. They evolved this machinery on a historical lineage distant from our own. Where their minds differ from ours, they show us another way of being a sentient organism. Where we are similar, this is due to the convergence of distinct evolutionary paths. I introduced the topic just now as 'the mind.' This is a contentious term to use. What is it to have a mind? One option is that we are looking for something close to what humans have –– something like reflective and conscious thought. This sets a high bar for having a mind. Another possible view is that whenever organisms adapt to their circumstances in real time by adjusting their behavior, taking in information and acting in response to it, there is some degree of mentality or intelligence there. To say this sets a low bar. It is best not to set bars in either place. Roughly speaking, we are dealing with a matter of degree, though 'degree' is not quite the right term either. The evolution of a mind is the acquisition of a tool-kit for the control of behavior. The tool-kit includes some kind of perception, though different animals have very different ways of taking in information from the world. -

"Higher" Cognition. Animal Sentience

Animal Sentience 2017.030: Vallortigara on Marino on Thinking Chickens Sentience does not require “higher” cognition Commentary on Marino on Thinking Chickens Giorgio Vallortigara Centre for Mind/Brain Sciences University of Trento, Italy Abstract: I agree with Marino (2017a,b) that the cognitive capacities of chickens are likely to be the same as those of many others vertebrates. Also, data collected in the young of this precocial species provide rich information about how much cognition can be pre-wired and predisposed in the brain. However, evidence of advanced cognition — in chickens or any other organism — says little about sentience (i.e., feeling). We do not deny sentience in human beings who, because of cognitive deficits, would be incapable of exhibiting some of the cognitive feats of chickens. Moreover, complex problem solving, such as transitive inference, which has been reported in chickens, can be observed even in the absence of any accompanying conscious experience in humans. Giorgio Vallortigara, professor of Neuroscience at the Centre for Mind/Brain Sciences of the University of Trento, Italy, studies space, number and object cognition, and brain asymmetry in a comparative and evolutionary perspective. The author of more than 250 scientific papers on these topics, he was the recipient of several awards, including the Geoffroy Saint Hilaire Prize for Ethology (France) and a Doctor Rerum Naturalium Honoris Causa for outstanding achievements in the field of psychobiology (Ruhr University, Germany). r.unitn.it/en/cimec/abc In a revealing piece in New Scientist (Lawler, 2015a) and a beautiful book (Lawler, 2015b), science journalist Andrew Lawler discussed the possible consequences for humans of the sudden disappearance of some domesticated species. -

Assessment of Emotional Functioning in Pain Treatment Outcome Research

Assessment of emotional functioning in pain treatment outcome research Robert D. Kerns, Ph.D. VA Connecticut Healthcare System Yale University Running head: Emotional functioning Correspondence: Robert D. Kerns, Ph.D., Psychology Service (116B), VA Connecticut Healthcare System, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, CT 06516; Phone: 203-937- 3841; Fax: 203-937-4951; Electronic mail: [email protected] Emotional Functioning 2 Assessment of Emotional Functioning in Pain Treatment Outcome Research The measurement of emotional functioning as an important outcome in empirical examinations of pain treatment efficacy and effectiveness has not yet been generally adopted in the field. This observation is puzzling given the large and ever expanding empirical literature on the relationship between the experience of pain and negative mood, symptoms of affective distress, and frank psychiatric disorder. For example, Turk (1996), despite noting the high prevalence of psychiatric disorder, particularly depression, among patients referred to multidisciplinary pain clinics, failed to list the assessment of mood or symptoms of affective distress as one of the commonly cited criteria for evaluating pain outcomes from these programs. In a more recent review, Turk (2002) also failed to identify emotional distress as a key index of clinical effectiveness of chronic pain treatment. A casual review of the published outcome research in the past several years fails to identify the inclusion of measures of emotional distress in most studies of pain treatment outcome, other than those designed to evaluate the efficacy of psychological interventions. In a recent edited volume, The Handbook of Pain Assessment (Turk & Melzack, 2001), several contributors specifically encouraged inclusion of measures of psychological distress in the assessment of pain treatment effects (Bradley & McKendree-Smith, 2001; Dworkin, Nagasako, Hetzel, & Farrar, 2001; Okifuji & Turk, 2001). -

The Psychology of Euthanizing Animals: the Emotional Components

F. Turner and J. Strak Comment ORIGINAL ARTICLE food. Apart from this, there are likely to be large adjustmentcosts borne by pro ducers (at home and abroad) as existing production systems are discarded in The Psychology favor of those advocated by the welfare groups. Furthermore, the adoption of these less intensive forms of farming may result in a completely different pattern of Euthanizing Animals: of labor and capital use in the U.K. farming sector. The subject of animal welfare is undoubtedly one of great public concern. The Emotional Components However, it is also one of great complexity, and if changes in the regulations governing animal production methods are to be made, those changes should take full account of the implications for producers, consumers and society in general. The farming industry should not interpret the interest in animal welfare as a Charles E. Owens, Ricky Davis threat to its livelihood nor should consumers dismiss lightly the likely changes in costs or structure of farming that may result from a revision of the Codes of Prac and Bill Hurt Smith* tice relating to animal welfare. The appropriate animal welfare policy for society will be identified only when all the interested parties become fully aware of the consequences of their actions. [Ed. Note: Independent of any proposed changes in the British Codes of Prac Abstract tice, the U.K. veal calf industry (Quantock Veal) has taken the initiative of switch The emotional effects of euthanizing unwanted animals on professional ani ing from individual crate rearing to the use of straw-fi.lled group pens. -

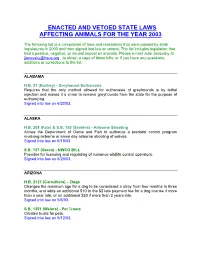

Enacted and Vetoed State Laws Affecting Animals for the Year 2003

ENACTED AND VETOED STATE LAWS AFFECTING ANIMALS FOR THE YEAR 2003 The following list is a compilation of laws and resolutions that were passed by state legislatures in 2003 and then signed into law or vetoed. The list includes legislation that had a positive, negative, or neutral impact on animals. Please e-mail Julie Janovsky at [email protected] , to obtain a copy of these bills, or if you have any questions, additions or corrections to the list. ALABAMA H.B. 37 (Buskey) - Greyhound Euthanasia Requires that the only method allowed for euthanasia of greyhounds is by lethal injection and makes it a crime to remove greyhounds from the state for the purpose of euthanizing. Signed into law on 6/20/03. ALASKA H.B. 208 (Fate) & S.B. 155 (Seekins) - Airborne Shooting Allows the Department of Game and Fish to authorize a predator control program involving airborne or same day airborne shooting of wolves. Signed into law on 6/18/03 S.B. 147 (Green) - NWCO BILL Provides for licensing and regulating of nuisance wildlife control operators. Signed into law on 6/28/03. ARIZONA H.B. 2121 (Carruthers) - Dogs Changes the minimum age for a dog to be considered a stray from four months to three months, and adds an additional $10 to the $2 late payment fee for a dog license if more than a year late, or an additional $20 if more than 2 years late. Signed into law on 5/6/03. S.B. 1351 (Weiers) - Pet Trusts Creates trusts for pets. Signed into law on 5/12/03. -

Thanatology Graduate Certificate — Online

Thanatology Graduate Certificate — Online Inspired to learn Required coursework Thanatology is the interdisciplinary and scientific study of the Certificate Core Curriculum (12 credits): dying and grieving process; social attitudes toward death; ritual Course # Course name Credits and memorialization; and the social, spiritual, psychological, and THA 605 Foundations of Thanatology 3 medical aspects of death, dying, loss, and bereavement. THA 615 Bereavement Theory & Practice 3 Marian’s graduate certificate in thanatology assists students in achieving their educational goals while serving the community THA 625 Theological Perspectives in Thanatology 3 in times of need. THA 640 Applied Ethics & the End of Life 3 Designed for students who already hold a master’s degree in Electives (6 credits): another discipline, the graduate certificate curriculum consists of Course # Course name Credits four core curriculum courses (12 credits) and two electives THA 630 Thanatology Research Methods 3 (6 credits) for a total of 18 credits. Courses in the graduate THA 705 Death in the Lives of Children & Teens 3 certificate program may be waived by the program director THA 715 Bereavement after Unnatural Death 3 contingent on equivalent experience or coursework. THA 725 Bereavement Program Development 3 THA 735 Palliative & Hospice Care 3 Inspired to lead THA 745 Spiritual Formation & Thanatology 3 THA 710 Understanding Suicide 3 The program combines rigorous study across the spectrum of THA 720 Children, Teens & Suicide 3 end-of-life studies with content in palliative and hospice care, THA 730 Suicide Prevention & Postvention 3 ethics, spirituality and religion, suicide, suicide prevention, THA 755 Death & the Literary Imagination 3 unnatural death, end-of-life decision-making, communication with service providers and families, program development and assessment, diversity, death education, and a core curriculum grounded in thanatology theory and practice. -

What We Mean When We Talk About Suffering—And Why Eric Cassell Should Not Have the Last Word

What We Mean When We Talk About Suffering—and Why Eric Cassell Should Not Have the Last Word Tyler Tate, Robert Pearlman Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Volume 62, Number 1, Winter 2019, pp. 95-110 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/722412 Access provided at 26 Apr 2019 00:52 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle What We Mean When We Talk About Suffering—and Why Eric Cassell Should Not Have the Last Word Tyler Tate* and Robert Pearlman† ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the phenomenon of suffering and its relation- ship to medical practice by focusing on the paradigmatic work of Eric Cassell. First, it explains Cassell’s influential model of suffering. Second, it surveys various critiques of Cassell. Next it outlines the authors’ concerns with Cassell’s model: it is aggressive, obscure, and fails to capture important features of the suffering experience. Finally, the authors propose a conceptual framework to help clarify the distinctive nature of sub- jective patient suffering. This framework contains two necessary conditions: (1) a loss of a person’s sense of self, and (2) a negative affective experience. The authors suggest how this framework can be used in the medical encounter to promote clinician-patient communication and the relief of suffering. *Center for Ethics in Health Care and School of Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. †National Center for Ethics in Health Care, Washington, DC, and School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Correspondence: Tyler Tate, Oregon Health and Science University, School of Medicine, Depart- ment of Pediatrics, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR 97239-3098. -

A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O

Life at War and the Heroic Illusions Created to Cope with War: A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien By Gaye L. Allen A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies written under the direction of Professor Richard M. Drucker and approved by ________________________ Richard Drucker Camden, New Jersey May 2011 i Abstract of the Thesis Life at War and the Illusions Created to Cope with War: A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien By Gaye L. Allen Thesis Director: Professor Richard M. Drucker This thesis will examine the fictional war novels, The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane and Going after Cacciato by Tim O‘Brien. It will examine the heroic illusions created by soldiers on the frontline as psychological coping mechanisms as a means to escape the realities of war. It will also examine how Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien create protagonists and characters that struggle to understand the conflicts within themselves as consequences of their developing point of view toward themselves, their war comrades, and their society‘s values and how each of these writers through observing battlefield experience comes to question the meaning of war and its effects. Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien investigate the moral and cultural values of their respective societies. Crane portrays the Victorian era O‘Brien examines1960‘s America. Each novel asks us to view their war with both irony and sympathy. -

Mourning Dove (Zenaida Macroura)

Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) February 2006 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet Number 31 General information The mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) is one of the most widely distributed and abundant birds in North America. Fall populations of this game bird in the United States are estimated to be slightly more than 400 million birds. In recent years, the annual harvest by hunting in the United States has been estimated at 18 to 25 million birds, similar to the harvest of all oth- er migratory game birds combined. Mourning doves are highly adaptable, occurring in most ecological types except marshes and heavily forested areas. The mourning dove is a medium-sized member of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Columbidae family. While this family consists of ap- Mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) proximately 300 species of doves and pigeons, only 8 species, including the mourning dove, are native tends his wings and begins a long spiraling glide back to the United States. The mourning dove is approxi- down. The perch coo is one of the few vocalizations mately 11 to 13 inches in length, with a 17– to 19–inch that mourning doves make. It consists of one note fol- wingspan, weighing on average 4.4 ounces. Mourning lowed by a higher one, then three to five notes held at doves have delicate bills and long, pointed tails. They great length, and it is used by males to court females. are grayish-brown and buff in color, with black spots A female will respond to the perch coo in one of three on wing coverts and near ears. -

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition*

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition* Members of the Panel on Euthanasia Steven Leary, DVM, DACLAM (Chair); Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, High Ridge, Missouri Wendy Underwood, DVM (Vice Chair); Indianapolis, Indiana Raymond Anthony, PhD (Ethicist); University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Samuel Cartner, DVM, MPH, PhD, DACLAM (Lead, Laboratory Animals Working Group); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama Temple Grandin, PhD (Lead, Physical Methods Working Group); Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado Cheryl Greenacre, DVM, DABVP (Lead, Avian Working Group); University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee Sharon Gwaltney-Brant, DVM, PhD, DABVT, DABT (Lead, Noninhaled Agents Working Group); Veterinary Information Network, Mahomet, Illinois Mary Ann McCrackin, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACLAM (Lead, Companion Animals Working Group); University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Robert Meyer, DVM, DACVAA (Lead, Inhaled Agents Working Group); Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi David Miller, DVM, PhD, DACZM, DACAW (Lead, Reptiles, Zoo and Wildlife Working Group); Loveland, Colorado Jan Shearer, DVM, MS, DACAW (Lead, Animals Farmed for Food and Fiber Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Tracy Turner, DVM, MS, DACVS, DACVSMR (Lead, Equine Working Group); Turner Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery, Stillwater, Minnesota Roy Yanong, VMD (Lead, Aquatics Working Group); University of Florida, Ruskin, Florida AVMA Staff Consultants Cia L. Johnson, DVM, MS, MSc; Director, -

25 Positive Emotions in Human-Product Interactions

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Faces of Product Pleasure: 25 Positive Emotions in Human-Product Interactions Pieter M. A. Desmet Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, Delft, The Netherlands The study of user emotions is hindered by the absence of a clear overview of what positive emotions can be experienced in human- product interactions. Existing typologies are either too concise or too comprehensive, including less than five or hundreds of positive emotions, respectively. To overcome this hindrance, this paper introduces a basic set of 25 positive emotion types that represent the general repertoire of positive human emotions. The set was developed with a componential analysis of 150 positive emotion words. A questionnaire study that explored how and when each of the 25 emotions are experienced in human-product interactions resulted in a collection of 729 example cases. On the basis of these cases, six main sources of positive emotions in human-product interactions are proposed. By providing a fine-grained yet concise vocabulary of positive emotions that people can experience in response to product design, the typology aims to facilitate both research and design activities. The implications and limitations of the set are discussed, and some future research steps are proposed. Keywords – Emotion-Driven Design, Positive Emotions, Questionnaire Research. Relevance to Design Practice – Positive emotions differ both in how they are evoked and in how they influence usage behaviour. Designers can use the set of 25 positive emotions to develop their emotional granularity and to specify design intentions in terms of emotional impact. Citation: Desmet, P. M. A. (2012). Faces of product pleasure: 25 positive emotions in human-product interactions.