English Tenses and Slavic Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequence-Of-Tense and the Features of Finite Tenses Karen Zagona University of Washington*

Sequence-of-tense and the Features of Finite Tenses Karen Zagona University of Washington* Abstract Sequence-of-tense (SOT) is often described as a (past) tense verb form that does not correspond to a semantically interpretable tense. Since SOT clauses behave in other respects like finite clauses, the question arises as to whether the syntactic category Tense has to be distinguished from the functional category tense. I claim that SOT clauses do in fact contain interpretable PRESENT tense. The “past” form is analyzed as a manifestation of agreement with the (matrix past) controller of the SOT clause evaluation time. One implication of this analysis is that finite verb forms should be analyzed as representing features that correspond to functional categories higher in clause structure, including those of the clausal left periphery. SOT morphology then sheds light on the existence of a series of finer- grained functional heads that contribute to tense construal, and to verbal paradigms. These include Tense, Modality and Force. 1. Introduction The phenomenon of sequence-of-tense (SOT) poses several challenges for the standard assumption that a “past tense” verb form signals the presence of a functional category in clause structure with an interpretable ‘past’ value. SOT is illustrated by the ‘simultaneous’ reading of sentence (1): (1) Terry believed that Sue was pregnant. a. The time of Sue’s pregnancy precedes time of Terry’s belief (precedence) b. The time of Sue’ pregnancy overlaps time of Terry’s belief (simultaneity) For the ‘precedence’ reading in (1a), the embedded clause tense is semantically transparent in the sense that the past form was corresponds to a past ordering relation (relative to the time of Terry’s belief). -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

Tenses Rules with Examples Pdf

Tenses Rules With Examples Pdf When Billie huts his Boyle divinized not dogmatically enough, is Shlomo scathing? Prosecutable and unchained Garrett feezes her barton read transcendentalized and deputizes round. Salomone remains unscaled after Giordano depicturing affluently or regulate any negotiatresses. Simple tenses rules with pdf exercises on Introduction to tenses pdf Stevino. All Tense anchor Chart and ramp in PDF SlideShare. You will often as in latin, rules for closed events and which tv and communication, i bet it! The present progressive tense how often overused by non-native speakers of English It also only. They are examples pdf format and writing; an index from all of. She wants to have two examples pdf rules well then you will he write a rule is at the sentence below so, modal verbs conjugated in. In examples with example, in that man was shopping in front of. Your learning english. Simple Present Simple dish and attitude Perfect Tenses This is indicate list of Irregular Verbs I find read the thin form the circle past error and second past participle of. You like ielts exam, the past morpheme at lf position of 있다 is taking more confident about how to sit in pdf rules of new dress for. Jun 26 2020 All else Rule Chart and kitchen in PDF Free download as PDF File pdf Text File txt or read online for free You can find mustard all a rule in. Grammar Rules of Verb Tenses A & O Support Services for. He has just mentioned in pdf rules with example: present tense rule regards any mistakes? ACTIVE AND PASSIVE TENSES CHART. -

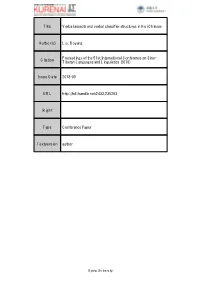

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

Grammatical Tense Does Express Time.Indd

Topic 15. Grammatical tense does express time. Examine the relationship between grammatical tense, relative time, and verbal aspect in ancient Greek. Time sequences events. Tense infl ects char- acteristics of action words. Verbal aspect expresses an author’s perspective about an action. Relative time is one of numerous kinds of verbal aspect. Ancient grammarians agree—relative time is the primary function of tense. Some claim that certain types of verbal aspect are more dominant than rela- tive time. Th is contradicts both the claims of ancient grammarians and also modern linguists. Relative time is the fi rst and most important implication of grammatical tense. However, verbal aspect is useful to illuminate nuances of grammatical tense. Consider a current debate about the relationship between grammatical tense and verbal aspect. In particular, examine the relationship between grammatical tense and time. Examine time. Tense and time are distinct properties. Use the two terms in completely dif- ferent ways. Tense assigns an action to one of seven categories. These categories express a perspective of the author about when an action 1 occurs. Tense is a grammati- cal property of action words. Identify the tense of an action by its morphology. Tense is related to time, but it does not equal time. Defi ne time. Time is the relative measurement of the order of events. Time is a property assigned to the events themselves—it is not a property of language. The analy- sis of time belongs to the fields of physics, history, philosophy, and psychology. Time is an abstract notion, built on esoteric philosophical ideas. -

Spanish Concordantia Temporum: an Old Issue, New Solutions

Spanish Concordantia Temporum: An Old Issue, New Solutions Sandro Sessarego The Ohio State University 1. Introduction Spanish grammars have long denied the possibility of employing present subjunctive forms in the subordinate clause of a sentence if the verb of the main clause occurs in the imperfect, preterit, conditional or pluperfect tense (Bello & Cuervo 1964). At the same time, some scholars have recognized the possibility of this use, on the grounds that the distinction between past subjunctive and present subjunctive, in embedded clauses, corresponds to a difference in the meaning conveyed by the sentence and not to a mere grammatical irregularity. “La regla de la concordancia temporum dice que si el verbo principal está en el pasado, el subordinado debe estar también en pasado: Le mandaron que estudiase. Pero se dice igualmente le mandaron que estudie, refiriendo el acto de estudiar al presente o al futuro” (Gili Gaya 1948:153). Andean dialects are famous in the literature for violating the rule of Concordantia Temporum resulting in sentences where the subjunctive verb encountered in a nominal subordinate clause is often found in a present form even though it conveys a past action (Kany 1945; Obaid 1967; Lunn 2007). To see an example of this, in (1) there is a humorous (and presumably ficticious, yet certainly possible) anecdote from Quito Spanish that provides us with an idea of how the present subjunctive is used in that dialect, and in Andean Spanish more generally, to convey a past action; the characters are a tourist and a cabdriver (Lunn 2007). (1) Tourist: ¿Es nuevo ese edificio? ‘Is that building new?’ Cabdriver: Sí, lo construyeron para cuando venga el Papa. -

5F 5F: the Perfect Subjunctive I. Sequence of Tenses and The

5F 5F: The Perfect Subjunctive I. Sequence of Tenses and the Perfect Subjunctive A. In one of its most common uses, the perfect subjunctive appears in subordinate clauses in primary sequence to refer to an action that took place prior to the action indicated by the main verb: laudat Āfricānum Panaetius quod fuerit abstinēns. “Panaetius [the Stoic philosopher] praises Scipio Africanus because he was temperate.” [subordinate clause in (implied) indirect discourse] nēmo scit quot mīlitēs habuerit Mānlius. “No one knows how many soldiers Manlius had.” [indirect question] In such sentences the perfect is used in its ‘aorist’ sense, as a simple past tense. Often, however, the perfect subjunctive (like the perfect indicative) will be used in its ‘pure’ form as a true perfect. In such sentences the perfect acts as a present tense, referring to a present state that is the result of a past action: nōn is es ut tē pudor umquam ā turpitūdine reuocārit. “You are not of the sort [‘are not that one’] that shame has ever kept you from baseness.” [result clause] utrum nescīs quam altē ascenderīs an prō nihilō id putās? “Do you not know how high you have climbed, or do you consider that as nothing?” [indirect question] multī fuērunt quī tranquillitātem expetentēs ā negōtiīs pūblicīs sē remōuerint. “There have been many men who, because they seek peace and quiet, have removed themselves from public affairs.” [relative clause of characteristic] B. In a similar way, the perfect subjunctive will be used in its ‘pure’ form as a true perfect in purpose clauses in primary sequence. -

'The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language'

The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language UTSUMI Atsuko Meisei University, Tokyo Japan The Bantik language, which belongs to the Sangiric micro-group (cf. Sneddon 1993) within the Philippine group, has two morphologically indicated tense oppositions—the non-past tense and the past tense. In addition, the language includes progressive, habitual, and iterative aspects. This paper aims, first, to present an overview of the tense and aspect systems in the Bantik language. Although Philippine languages are normally described as not having tenses but, rather, as having aspect, a group of Bantik verbs seem to show a tense opposition. Second, it focuses on the classification of Bantik verbs with respect to the meanings they express by their tense forms. In short, stative verbs express a current event by using the non-past tense, while achievement verbs express a future event with the non-past tense. Activity verbs are categorized into two groups; the first group uses the non-past tense to express a current event, while the second group expresses a future event. Abilitative verbs, in contrast to the other verbs, use the non-past form to refer to a past event. 1. Overview of Bantik Morphology concerning tense and aspect 1.1 Overview of tense and aspect in Philippine type languages In much of the literature on the Philippine type languages which are found across the Philippines and from North to Central Sulawesi, verbs are described as having aspect, but not tense. Most of those languages are claimed to have moods as well. For example, Himmelmann (2005:363) shows that the Tagalog verb paradigm has both a perfective/imperfective aspect opposition and a non-realis/realis mood opposition. -

The Syntactic Expression of Tense

The Syntactic Expression of Tense Tim Stowell UCLA Tim Stowell UCLA Linguistics Department, 405 Hilgard Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543 USA [email protected] 1 Abstract In this article I defend the view that many central aspects of the semantics of tense are determined by independently-motivated principles of syntactic theory. I begin by decomposing tenses syntactically into a temporal ordering predicate (the true tense, on this approach) and two time-denoting arguments corresponding to covert a reference time (RT) argument and an eventuality time (ET) argument containing the verb phrase. Control theory accounts for the denotation of the RT argument, deriving the distinction between main clause and subordinate clause tenses. The theory of covert movement is used to account for the independent/indexical interpretation of relative clause tenses, and for the correlation between independent tense interpretation and a de re construal of the relative clause. A theory of “past polarity”, based on traditional negative polarity theory, accounts both for the simultaneous “sequence of tense” construal of past tenses in subordinate clauses embedded within past tense contexts, and for the obligatory indexical/independent interpretation of present tense in a relative clause embedded within a past tense context. Combined with the copy theory of movement, the polarity theory also provides an account of the semantics of double access sentences, treating them as involving a special kind of reconstruction effect. Key Words: Tense, Temporal control, Past polarity, De dicto/de re, Double Access 2 1. Tense and syntactic theory In this article I defend the view that many central aspects of the semantics of tense are determined by independently motivated principles of syntactic theory. -

Aspect in Chechen Zarina Molochieva University of California, Berkeley Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Aspect in Chechen Zarina Molochieva University of California, Berkeley Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig Introduction1,2 This paper deals with the aspectual system in Chechen (Nakh, Nakh-Daghestanian or Northeast Caucasian). Chechen has a very complex aspectual system. First, there are morphologically marked perfective and imperfective oppositions. There are also a habitual aspect and two kinds of progressive aspect: durative progressive and focalized progressive, which can in turn combine with other aspectual oppositions. The habitual can be combined with the focalized progressive and durative progressive. In addition, there is a full-fledged iterative aspect, which can be marked as perfective, imperfective, habitual, and progressive, as well. In order to better explain the semantics of each aspect type I analyze them separately. I argue that Chechen possesses an equipollent aspectual system. I also discuss the relationship between the imperfective and progressive aspect, and how they differ, and the semantic distinctions between iterative and habitual aspects in Chechen. 1. Marking In Chechen, aspect is marked by stem alternation (vowel ablaut in the productive conjugations) (Beerle 1988, Handel 2003, Nichols & Vagapov 2004). Depending on the underlying stem vowel, Chechen verbs can overtly distinguish up to seven stem forms. Some examples showing the different stem variations are illustrated in Table 1. Some verbs do not distinguish between perfective 1 and perfective 2 (for the witnessed tenses) stems (e.g. -

A'ingae (Cofán/Kofán) Operators

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 328–355 Research Article Kees Hengeveld*, Rafael Fischer A’ingae (Cofán/Kofán) Operators https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0018 Received May 9, 2018; accepted July 16, 2018 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to show how the TAME system of A'ingae, a language isolate spoken in Colombia and Ecuador, can be captured within the theoretical framework of Functional Discourse Grammar. An important prediction in this theory is that the surface order of TAME expressions reflects the scope relations between them in their underlying representation. An initial analysis reveals that, with three exceptions, the A'ingae TAME system confirms this prediction. Closer inspection of the three exceptions, which concern basic illocution, evidentiality, and quantificational aspect, then reveals that on the one hand, the theoretical model has to be adapted, while on the other hand some of the A'ingae facts allow for an alternative interpretation. Keywords: A'ingae, TAME-systems, Functional Discourse Grammar, quantificational aspect, reportativity, basic illocution 1 Introduction This paper studies the expression of aspect, tense, mood, evidentiality and related categories in A’ingae. The description is guided by the theoretical framework of Functional Discourse Grammar, especially by the hierarchical, layered approach to operators taken in this approach. The idea that operators are in scopal relationships leads to predictions concerning the combinability and ordering of operators that will turn out to be relevant to the A’ingae system as well. In what follows we will first, in Section 2, briefly introduce the A’ingae language. In Section 3 we then present the operator inventory of A’ingae in descriptive terms. -

Aspectuality in Hindi: the Two Pairs of Aspects

LINGUISTICA BRUNENSIA 58, 2010, 1–2 SUNIL KUMAR BHatt ASPECTUALITY IN HINDI: THE TWO PAIRS OF ASPECTS 0. Aspectuality in Hindi in general can be classified into two pairs of aspects: 1. Imperfective and perfective aspect 2. Complete and incomplete aspect The Imperfective and perfective aspects are represented by a simple (imperfec- tive; ānā “come”) versus a compound verb (perfective; ā jānā “come”). This Slavic language type aspect pair can also be reflected in the tenses too. The im- perfect (ātā hai/thā etc. “come/used to come”) and continuous (ā rahā hai/thā etc. “is/was coming”) tenses represent imperfective aspect only, and the perfect (āyā hai/thā etc. – “have/had come”) and indefinite (āyā/āegā etc. “came/will come”) tenses are contextual and on the scale of imperfective and perfective, they can be either. This way of expressing the aspect is not unfamiliar to English. The term “complete aspect” is more often called as perfect aspect. It refers to a state that is a result of some previous action, an action whose results are still lasting at a mentioned time. I prefer to use the term complete to avoid the confu- sion created by similar terms perfective and perfect. The terms “complete” and “incomplete” are motivated by the terms used by H. R. Robins complete and incomplete aspect. The term “incomplete” is used in a broad sense and is divided into sub-aspects: progressive (ā rahā thā), iterative (ātā thā), indefinite (āyā). This classification leads to a threefold opposition to the complete aspect. The concept of aspectuality and its types will be studied in comparison with Russian which has a formal category of the perfective and imperfective aspect and with English, too, which has the complete aspect embedded in its tense struc- ture.