The Many Dimensions of the Chief Justice's Triumphant Term

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020 Aaron Nisenson, Senior Counsel American Association of University Professors I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 II. First Amendment and Speech Rights ...................................................................................... 5 A. Garcetti / Citizen Speech ......................................................................................................... 5 Lane v. Franks, 134 S. Ct. 2369 (2014) .................................................................................. 5 B. Faculty Speech ......................................................................................................................... 5 Demers v. Austin, 746 F.3d 402 (9th Cir. 2014) .................................................................... 5 Wetherbe v. Tex. Tech Univ. Sys., 699 F. Appx 297 (5th Cir. 2017); Wetherbe v. Goebel, No. 07-16-00179-CV, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 1676 (Mar. 6, 2018) ................................... 5 Buchanan v. Alexander, 919 F.3d 847 (5th Cir. March 22, 2019) ......................................... 6 EXECUTIVE ORDER, Improving Free Inquiry, Transparency, and Accountability at Colleges and Universities (D. Trump March 21, 2019) ........................................................ 8 C. Union Speech............................................................................................................................ 9 Meade v. Moraine Valley Cmty. -

19-267 Our Lady of Guadalupe School V. Morrissey-Berru (07/08/2020)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL v. MORRISSEY- BERRU CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–267. Argued May 11, 2020—Decided July 8, 2020* The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions “to de- cide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, this Court held in Hosanna- Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 171, that the First Amendment barred a court from entertaining an employment discrimination claim brought by an elementary school teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious school where she taught. Adopting the so-called “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain key employees, the Court found relevant Perich’s title as a “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” her educational training, and her respon- sibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious ac- tivities. Id., at 190–191. -

First Amendment

FIRST AMENDMENT RELIGION AND FREE EXPRESSION CONTENTS Page Religion ....................................................................................................................................... 1063 An Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1063 Scholarly Commentary ................................................................................................ 1064 Court Tests Applied to Legislation Affecting Religion ............................................. 1066 Government Neutrality in Religious Disputes ......................................................... 1070 Establishment of Religion .................................................................................................. 1072 Financial Assistance to Church-Related Institutions ............................................... 1073 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time ...... 1093 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading ..................................................................................................................... 1094 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Restriction ................................................................................................................ 1098 Access of Religious Groups to Public Property ......................................................... 1098 Tax Exemptions of Religious Property ..................................................................... -

Oral Argument Before the Supreme Court of The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ------------------ OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL, ) Petitioner, ) v. ) No. 19-267 AGNES MORRISSEY-BERRU, ) Respondent. ) ------------------ ST. JAMES SCHOOL, ) Petitioner, ) v. ) No. 19-348 DARRYL BIEL, AS PERSONAL ) REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATE OF ) KRISTEN BIEL, ) Respondents. ) ------------------ Pages: 1 through 100 Place: Washington, D.C. Date: May 11, 2020 HERITAGE REPORTING CORPORATION Official Reporters 1220 L Street, N.W., Suite 206 Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 628-4888 www.hrccourtreporters.com Official - Subject to Final Review 1 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 2 ------------------ 3 OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL, ) 4 Petitioner, ) 5 v. ) No. 19-267 6 AGNES MORRISSEY-BERRU, ) 7 Respondent. ) 8 ------------------ 9 ST. JAMES SCHOOL, ) 10 Petitioner, ) 11 v. ) No. 19-348 12 DARRYL BIEL, AS PERSONAL ) 13 REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATE OF ) 14 KRISTEN BIEL, ) 15 Respondents. ) 16 ------------------ 17 Washington, D.C. 18 Monday, May 11, 2020 19 20 The above-entitled matter came on for 21 oral argument before the Supreme Court of the 22 United States at 11:35 a.m. 23 24 25 Heritage Reporting Corporation Official - Subject to Final Review 2 1 APPEARANCES: 2 ERIC C. RASSBACH, Esquire, Washington, D.C.; 3 on behalf of the Petitioners. 4 MORGAN L. RATNER, Assistant to the Solicitor 5 General, Department of Justice, 6 Washington, D.C.; 7 for the United States, as amicus curiae, 8 supporting the Petitioners. 9 JEFFREY L. FISHER, Esquire, Menlo Park, California; 10 on behalf of the Respondents. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Heritage Reporting Corporation Official - Subject to Final Review 3 1 C O N T E N T S 2 ORAL ARGUMENT OF: PAGE: 3 ERIC C. -

The Constitution United States of America

ThisThis publicationpublication supplementssupplements SenateSenate DocumentDocument 115–8,112–9, TheThe ConstitutionConstitution of the UnitedUnited StatesStates ofof America:America: Analysis Analysis andand InterpretationInterpretation—it––it shouldshould bebe insertedinserted intointo thethe pocketpocket onon thethe insideinside backback covercover ofof thatthat volumevolume 115th116th Congress DOCUMENT SENATE 2nd2d Session Session No.No. 116–20 115–8 " ! THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION 20202018 SUPPLEMENTSUPPLEMENT ANALYSISANALYSIS OFOF CASESCASES DECIDEDDECIDED BYBY THE SUPREME COURTCOURT OFOF THETHE UNITED STATES TO JUNEJULY 14,28, 20202018 PREPARED BY BY THE THE CCONGRESSIONALONGRESSIONAL RRESEARCHESEARCH SSERVICEERVICE LIBRARY OF OF CCONGRESSONGRESS VALERIE BBRANNONRANNON CAITLAINVICTORIADEVEREAUX KILLIONLEWIS ANDREW NNOLANOLAN ATTORNEY EEDITORSDITORS GEORGIA GKOULGKOUNTINA SMUMMEREGHAN NORWOODTOTTEN MLEGHANEGAL E TDITORSOTTEN LEGAL EDITORS U.S.U.S. GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT PUBLISHINGPUBLISHING OFFICE 31–34442-432 WASHINGTONWASHINGTON : : 20202018 Online Version: Online www.gpo.gov/constitutionannotated; Version: www.gpo.gov/constitutionannotated www.constitution.congress.gov For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 ISBNISBN 978-0-16-095800-7978-0-16-094937-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... -

Panel: Legal Issues in Higher Education: Annual Review of Court and Administrative Developments (CLE) Aaron Nisenson AAUP

Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy Volume 0 National Center Proceedings 2019 Article 54 April 2019 Panel: Legal Issues in Higher Education: Annual Review of Court and Administrative Developments (CLE) Aaron Nisenson AAUP Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba Part of the Collective Bargaining Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Nisenson, Aaron (2019) "Panel: Legal Issues in Higher Education: Annual Review of Court and Administrative Developments (CLE)," Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy: Vol. 0 , Article 54. Available at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba/vol0/iss14/54 This Proceedings Material is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nisenson: Panel: Legal Issues in Higher Education: Annual Review of Court a 46th Annual National Conference National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions Hunter College, the City University of New York March, 2019 Legal Update Aaron Nisenson Senior Counsel American Association of University Professors Published by The Keep, 2019 1 Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy, Vol. 0, Iss. 14 [2019], Art. 54 Annual Legal Update March, 2019 Aaron Nisenson, Senior Counsel American Association of University Professors I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... -

Ministerial Exception’ Covers Lay School Teachers by Dylan B

Publications U.S. Supreme Court Hears Argument on Whether ‘Ministerial Exception’ Covers Lay School Teachers By Dylan B. Carp, Paul Patten, Cecilie E. Read and Abraham N. Saiger May 12, 2020 Meet the Authors Whether the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses prevent civil courts from adjudicating employment discrimination claims brought by employees against their religious employer, where the employee carried out important religious functions, is the question presented in two consolidated cases before the U.S. Supreme Court: Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, No. 19-267, and St. James School v. Biel, No. 19-348. Dylan B. Carp (See our article on the Courts grant of review, U.S. Supreme Court to Decide Whether Ministerial Principal Exception Covers Catholic School Teachers.) San Francisco 415-796-5425 Email In both actions, the district courts granted the schools motion to dismiss on the ground the ministerial exception applied to the plaintiffs and therefore, provided immunity to the schools. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed the lower court decisions in both cases, holding the teachers were not covered by the exception, because neither the teachers nor the schools considered them to be ministers, as reflected in their job titles. In 2012, the Supreme Court decided Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. EEOC, 565 U.S. 171, recognizing the ministerial exception, a First Amendment doctrine that bars civil courts from adjudicating employment-related cases brought by “ministerial employees against their religious Paul Patten employers. The Supreme Courts decision in Hosanna-Tabor was unanimous. Principal Chicago 312-803-2570 In Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. -

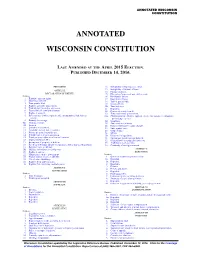

Annotated Wisconsin Constitution

ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION LAST AMENDED AT THE APRIL 2015 ELECTION. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 14, 2016. PREAMBLE 12. Ineligibility of legislators to office. 13. Ineligibility of federal officers. ARTICLE I. 14. Filling vacancies. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS. 15. Exemption from arrest and civil process. Section 16. Privilege in debate. 1. Equality; inherent rights. 17. Enactment of laws. 2. Slavery prohibited. 18. Title of private bills. 3. Free speech; libel. 19. Origin of bills. 4. Right to assemble and petition. 20. Yeas and nays. 5. Trial by jury; verdict in civil cases. 21. Repealed. 6. Excessive bail; cruel punishments. 22. Powers of county boards. 7. Rights of accused. 23. Town and county government. 8. Prosecutions; double jeopardy; self−incrimination; bail; habeas 23a. Chief executive officer to approve or veto resolutions or ordinances; corpus. proceedings on veto. 9. Remedy for wrongs. 24. Gambling. 9m. Victims of crime. 25. Stationery and printing. 10. Treason. 26. Extra compensation; salary change. 11. Searches and seizures. 27. Suits against state. 12. Attainder; ex post facto; contracts. 28. Oath of office. 13. Private property for public use. 29. Militia. 14. Feudal tenures; leases; alienation. 30. Elections by legislature. 15. Equal property rights for aliens and citizens. 31. Special and private laws prohibited. 16. Imprisonment for debt. 32. General laws on enumerated subjects. 17. Exemption of property of debtors. 33. Auditing of state accounts. 18. Freedom of worship; liberty of conscience; state religion; public funds. 34. Continuity of civil government. 19. Religious tests prohibited. 20. Military subordinate to civil power. ARTICLE V. 21. Rights of suitors. EXECUTIVE. 22. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______DONALD J

Nos. 16-1436, 16-1540 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Petitioners, v. INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, ET AL. Respondents. __________ DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Petitioners, v. STATE OF HAWAII, ET AL. Respondents. __________ ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEAL FOR THE FOURTH AND NINTH CIRCUITS __________ BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE BECKET FUND FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY IN SUPPORT OF NEITHER PARTY __________ MARK L. RIENZI Counsel of Record ERIC C. RASSBACH HANNAH C. SMITH DIANA M. VERM JOSEPH C. DAVIS RACHEL N. BUSICK THE BECKET FUND FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY 1200 New Hampshire Ave., NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20036 [email protected] (202) 955-0095 Counsel for Amicus Curiae QUESTION PRESENTED Executive Order No. 13,780, 82 Fed. Reg. 13,209 (Mar. 9, 2017) suspends for 90 days the entry of for- eign nationals from six Muslim-majority countries. Respondents allege, and each lower court that reached the question found, that the Executive Order imper- missibly targets Muslims. The question presented is: Whether the Executive Order’s alleged religious targeting should in the first instance be evaluated un- der the Establishment Clause or the Free Exercise Clause. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... v INTEREST OF THE AMICUS .................................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 6 I. The courts below incorrectly applied the Establishment Clause. ..................................... 6 A. Lemon provides a poor foundation for deciding Establishment Clause claims. ......................................................... 6 B. Both the majority and principal dissent in Town of Greece require a history-based approach to Establishment Clause claims. -

Annotated Wisconsin Constitution

ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION LAST AMENDED AT THE APRIL 2020 ELECTION. PUBLISHED JULY 23, 2021. PREAMBLE 12. Ineligibility of legislators to office. 13. Ineligibility of federal officers. ARTICLE I. 14. Filling vacancies. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS. 15. Exemption from arrest and civil process. Section 16. Privilege in debate. 1. Equality; inherent rights. 17. Enactment of laws. 2. Slavery prohibited. 18. Title of private bills. 3. Free speech; libel. 19. Origin of bills. 4. Right to assemble and petition. 20. Yeas and nays. 5. Trial by jury; verdict in civil cases. 21. Repealed. 6. Excessive bail; cruel punishments. 22. Powers of county boards. 7. Rights of accused. 23. Town and county government. 8. Prosecutions; double jeopardy; self−incrimination; bail; habeas 23a. Chief executive officer to approve or veto resolutions or ordinances; corpus. proceedings on veto. 9. Remedy for wrongs. 24. Gambling. 9m. Victims of crime. 25. Stationery and printing. 10. Treason. 26. Extra compensation; salary change. 11. Searches and seizures. 27. Suits against state. 12. Attainder; ex post facto; contracts. 28. Oath of office. 13. Private property for public use. 29. Militia. 14. Feudal tenures; leases; alienation. 30. Elections by legislature. 15. Equal property rights for aliens and citizens. 31. Special and private laws prohibited. 16. Imprisonment for debt. 32. General laws on enumerated subjects. 17. Exemption of property of debtors. 33. Auditing of state accounts. 18. Freedom of worship; liberty of conscience; state religion; public funds. 34. Continuity of civil government. 19. Religious tests prohibited. 20. Military subordinate to civil power. ARTICLE V. 21. Rights of suitors. EXECUTIVE. 22. -

Amici Curiae of the Center for Inquiry, Inc., American Atheists, Inc., and the American Humanist Association, in Support of Respondents ———— Nicholas J

Nos. 19-267 & 19-348 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL, Petitioner, v. AGNES MORRISEY-BERRU, Respondent. ———— ST. JAMES SCHOOL, Petitioner, v. DARRYL BIEL, AS PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATE OF KRISTEN BIEL, Respondent. ———— On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ———— BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY, INC., AMERICAN ATHEISTS, INC., AND THE AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ———— NICHOLAS J. LITTLE EDWARD TABASH CENTER FOR INQUIRY, INC. Counsel of Record 1012 14th St. NW, 11500 West Olympic Blvd., Suite 205 Suite 400 Washington, DC 20005 Los Angeles, CA 90064 (310) 279-5120 [email protected] [Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover] WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 ALISON M. GILL MONICA L MILLER AMERICAN ATHEISTS AMERICAN HUMANIST 718 7th St. NW, ASSOCIATION Washington DC 20001 1821 Jefferson Place NW, Washington DC 20036 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................ iii STATEMENT OF THE INTEREST ................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................. 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 6 I. THE FIRST AMENDMENT REQUIRES A NARROW MINISTERIAL EXCEP- TION .......................................................... 6 A. The Establishment Clause limits the scope of the ministerial exception ....... 7 B. Any ministerial exception must be narrow ................................................. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. ______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States MICHIGAN CATHOLIC CONFERENCE, CATHOLIC FAMILY SERVICES, THE CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF NASHVILLE, CATHOLIC CHARITIES OF TENNESSEE, INC., AQUINAS COLLEGE, DOMINICAN SISTERS OF ST. CECILIA CONGREGATION, MARY QUEEN OF ANGELS, INC., CAMP MARYMOUNT, INC., AND ST. MARY VILLA, INC., Petitioners, v. SYLVIA MATHEWS BURWELL, IN HER OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SECRETARY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI NOEL J. FRANCISCO MATTHEW A. KAIRIS JONES DAY Counsel of Record 51 Louisiana Ave., NW JONES DAY Washington, D.C. 325 John H. McConnell Blvd. 20001-2113 Suite 600 (202) 879-3939 Columbus, OH 43215 [email protected] (614) 469-3939 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners QUESTION PRESENTED This case presents the question this Court did “not decide” in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2751, 2782 & n.39 (2014): Whether, consistent with the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (“RFRA”), the Government can compel a nonprofit religious organization to act in violation of its sincerely held religious beliefs by participating in a regulatory scheme to provide its employees with coverage for abortion- inducing products, contraceptives, and sterilization. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING AND RULE 29.6 STATEMENT Petitioners, who were Plaintiffs below, are Michigan Catholic Conference; Catholic Family Services; the Catholic Diocese of Nashville; Catholic Charities of Tennessee, Inc.; Aquinas College, Nashville, Tennessee; Dominican Sisters of St. Cecilia Congregation; Mary Queen of Angels, Inc.; Camp Marymount, Inc.; and St.