Medication Management of Co-Occurring Opioid Use Disorder in Mental Health Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatment of Stimulant Use Disorders

UW PACC Psychiatry and Addictions Case Conference UW Medicine | Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences TREATMENT OF STIMULANT USE DISORDERS Matt Iles-Shih, MD Addiction Psychiatry Fellow University Of Washington & VA Puget Sound Health Care System UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington GENERAL DISCLOSURES The University of Washington School of Medicine also gratefully acknowledges receipt of educational grant support for this activity from the Washington State Legislature through the Safety-Net Hospital Assessment, working to expand access to psychiatric services throughout Washington State. UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington SPEAKER DISCLOSURES No conflicts of interest/disclosures UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington OBJECTIVES 1. Brief overview of stimulant-related physiology & epidemiology 2. Recognizing & treating stimulant use disorders: . Diagnosis & management of acute effects (brief) . Psychotherapies (brief) . Pharmacotherapies 3. Special populations – ADHD in stimulant-abusing pts: to Rx, and how? UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington STIMULANTS: What Substances Are We Talking About? Cocaine Amphetamines: – Prescription Meds – Methamphetamine – Multiple other modified amphetamines MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) [Note: mixed stimulant-psychodelic properties, w/↑serotonin > dopamine and abuse >> addiction.] Others: – Cathinones: Khat & Synthetics (e.g., “Bath Salts”) – Piperazine-like substances (various) – Phenylaklylpyrrolidines (various) UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington COMMONALITIES (WHAT MAKES A STIMULANT -

Cocaine Use Disorder

COCAINE USE DISORDER ABSTRACT Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem. Millions of Americans regularly use cocaine, and some develop a substance use disorder. Cocaine is generally not ingested, but toxicity and death from gastrointestinal absorption has been known to occur. Medications that have been used as substitution therapy for the treatment of a cocaine use disorder include amphetamine, bupropion, methylphenidate, and modafinil. While pharmacological interventions can be effective, a recent review of pharmacological therapy for cocaine use indicates that psycho-social efforts are more consistent over medication as a treatment option. Introduction Cocaine is an illicit, addictive drug that is widely used. Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem that burdens the healthcare system and that can be destructive to individual lives. It is impossible to know with certainty the extent of use but data from public health surveys, morbidity and mortality reports, and healthcare facilities show that there are millions of Americans who regularly take cocaine. Cocaine intoxication is a common cause for emergency room visits, and it is one drug that is most often involved in fatal overdoses. Some cocaine users take the drug occasionally and sporadically but as with every illicit drug there is a percentage of people who develop a substance use disorder. Treatment of a cocaine use disorder involves psycho-social interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com Pharmacology of Cocaine Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the Erthroxylum coca plant, a plant that is indigenous to South America and several other parts of the world, and is cultivated elsewhere. -

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

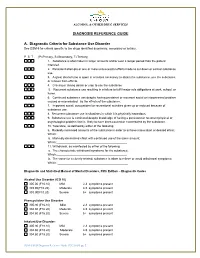

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

DSM-5 Diagnoses and New ICD-10-CM Codes

DSM-5 DiAgnoses And New ICD-10-CM Codes As Ordered in the DSM-5 Classification DSM-5 Recommended DSM-5 Recommended Disorder ICD-10-CM Code for use ICD-10-CM Code for use through September 30, 2017 beginning October 1, 2017 Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder F50.89 F50.82 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild F10.10 F10.10 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained remission F10.10 F10.11 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild F12.10 F12.10 Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F12.10 F12.11 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F16.10 F16.11 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or F16.20 F16.21 sustained remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F16.20 F16.21 remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild, In early or F16.10 F16.11 sustained remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, -

Stimulant Use Disorder

Public Meeting on Patient-Focused Drug Development for Stimulant Use Disorder Tuesday, October 6, 2020 FDA will be streaming a live webcast of the meeting with the presentation slides, which is open to the public at: http://fda.yorkcast.com/webcast/Play/89f7acb8d56e4de8827d1ade8efa42661d. The webcast recording and presentation slides, along with a meeting transcript and summary report, will also be made publicly available after the meeting. #PFDD Welcome Robyn Bent, RN, MS | CAPT, U.S. Public Health Service Director, Patient-Focused Drug Development Program Office of Center Director Center for Drug Evaluation and Research U.S. Food and Drug Administration Agenda • Opening Remarks • Setting the Context • Overview of FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative • Overview of Stimulant Use Disorder • Overview of Discussion Format • Discussion Topic 1: Health Effects and Daily Impacts • Break • Discussion Topic 2: Current Approaches to Management • Discussion Topic 3: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Stimulant Use Disorder • Closing Remarks www.fda.gov 3 Opening Remarks Admiral Brett P. Giroir, MD Assistant Secretary for Health United States Department of Health and Human Services Overview of FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative Theresa Mullin, PhD Associate Director for Strategic Initiatives Center for Drug Evaluation and Research U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA’s role in medical product development and evaluation Review divisions at FDA (e.g., Division of Neurology, Division While FDA plays a critical of Psychiatry, etc.) provide FDA’s mission is to protect and oversight role in drug regulatory oversight during promote public health by development, it is just one part drug development, make evaluating the safety and of the process. -

Substance Use Disorders

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS KEY POINTS OVERVIEW • Characterized by problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically It is not uncommon for adolescents to experiment significant impairment or distress. with a variety of substances, both legal and illegal. • Can include physical addiction, which is However, drug and alcohol use is a leading cause of characterized by intense cravings, morbidity and mortality among adolescents, and increased tolerance, and physical and experimentation can lead to substance use disorder. mental withdrawal symptoms. Studies have shown that children who experiment • Depending upon the substance, medically with substances at a young age are more likely to use supervised detoxification may be required. other drugs later in life. These findings highlight the • Evidence-based treatments include need to prevent drug initiation among adolescents and cognitive behavioral therapy, family children or delay it for as long as possible. therapies, and multisystemic therapy. Families should be aware of potential warning signs of drug use in adolescents. The first changes families often notice are in behavior and mannerisms. However, there are many warning signs, some of which include: • Fatigue • Red and glazed eyes • Lasting cough • Sudden mood changes • Irresponsible behavior or poor judgment • Depression • Breaking rules and withdrawing from the family • Loss of motivation or lack of interest in previous activities • Negative attitude • Drop in grades • New friends that are less interested in standard home and school -

Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders by Time Since First

Letters RESEARCH LETTER der and nicotine dependence did not differ between the 2 groups within 12 months of initiation but was higher for young Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders adults in subsequent periods. by Time Since First Substance Use Among young adults, prevalence of lifetime cocaine, meth- Among Young People in the US amphetamine, and heroin use in 2018 was 11.4% (95% CI, 10.7- Earlier age at drug initiation has been shown to be associated 12.1), 2.5% (95% CI, 2.2-2.8), and 1.3% (95% CI, 1.1-1.5), respec- with faster transition to substance use disorder (SUD).1 How- tively. Within 12 months of initiation, adjusted prevalence was ever, prevalence of specific SUDs as a function of time since higher for methamphetamine use disorder (24.8% [95% CI, first substance use among young people has not, to our knowl- 16.8-34.9]) and heroin use disorder (30.9% [95% CI, 20.6- edge, been investigated. We examined the prevalence of spe- 43.4]) than for cocaine use disorder (5.6% [95% CI, 4.2-7.4]). cific SUDs since first drug use (including tobacco, alcohol, can- Estimates for adolescents were not reported owing to limited nabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin) or prescription samples. misuse (including opioids, stimulants, and tranquilizers) in Prevalence of lifetime misuse of prescription drugs in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years and young adults aged 18 2014 was 9.2% (95% CI, 8.7-9.7) among adolescents and to 25 years. 26.3% (95% CI, 25.4-27.2) among young adults. -

Poster Session Imonday, December 7, 2015

Neuropsychopharmacology (2015) 40, S106–S271 & 2015 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/15 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session I from the Forest Research Institute/ Actavis; NIH/ NCCIH; Monday, December 7, 2015 NIMH M2. Mental Healthcare Access and the Underserved: Are M1. Changes in the Functional Brain Connectivity and Our State-of-the-Art Treatments Getting to those who Verbal Memory Performance Following Yoga or Need It Most? Memory Training in Older Adults with Subjective Memory Complaints Daniel Jimenez*, Benjamin Cook, Margarita Alegria, Stephen Bartels, Charles Reynolds, Philip Harvey Helen Lavretsky*, Hongyu Yang, Harris Eyre, Amber Leaver, Katherine Narr, Dharma Khalsa University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, United States University of California Los Angeles Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human Behavior, Los Angeles, Background: Disparities in mental health service use by racial/ California, United States ethnic minority older adults are well-documented. Attention is now turning to the question of whether racial/ethnic Background: Mind-body interventions, such as yoga, are disparities in mental healthcare are increasing or diminishing. used to reduce stress in the community samples. However, The net effect of changes in healthcare organization and clinical efficacy of such interventions for cognition remains immigration, along with any explicit policies designed to unclear. To-date, no studies have explored the effect of yoga reduce disparities, is not clear. The purpose of this study is to on cognition and resting state functional Magnetic Reso- examine national trends in the use of mental health services by nance Imaging (rs-fMRI). The present study was to explore older racial/ethnic minority adults. -

Pharmacotherapy for Stimulant Use Disorders: a Systematic Review

4 D epartment of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service Evidence-based Synthesis Program Pharmacotherapy for Stimulant Use Disorders: A Systematic Review August 2018 Prepared for: Investigators: Department of Veterans Affairs Principal Investigator: Veterans Health Administration Brian Chan, MD, MPH Quality Enhancement Research Initiative Co-Investigators: Health Services Research & Development Service Karli Kondo, PhD, MA Washington, DC 20420 Chelsea Ayers, BA Prepared by: Michele Freeman, MPH Jessica Montgomery, MPH Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) Robin Paynter, MLIS Portland VA Health Care System Devan Kansagara, MD, MCR Portland, OR Devan Kansagara, MD, MCR, Director 4 Pharmacotherapy for Stimulant Use Disorders Evidence-based Synthesis Program PREFACE The VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) was established in 2007 to provide timely and accurate syntheses of targeted healthcare topics of particular importance to clinicians, managers, and policymakers as they work to improve the health and healthcare of Veterans. QUERI provides funding for 4 ESP Centers, and each Center has an active University affiliation. Center Directors are recognized leaders in the field of evidence synthesis with close ties to the AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Centers. The ESP is governed by a Steering Committee comprised of participants from VHA Policy, Program, and Operations Offices, VISN leadership, field-based investigators, and others as designated appropriate by QUERI/HSR&D. The ESP Centers generate evidence syntheses on important clinical practice topics. These reports help: · Develop clinical policies informed by evidence; · Implement effective services to improve patient outcomes and to support VA clinical practice guidelines and performance measures; and · Set the direction for future research to address gaps in clinical knowledge. -

Stimulant Use Disorder

Disclosure Information Frances R. Levin, MD Support: Research/Salary/Training Support Federal: National Institute on Drug Abuse: National Institute on Drug Abuse: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) New York State: Salary Support- Research Scientist Industry Support: US World Meds (provides medication for study); Consultant: Major League Baseball Unpaid Scientific Advisory Board Member: Novartis, Alkermes, Indivior Everything I talk about is Off-Label Use No medication has been FDA-approved for the Treatment of Stimulant Use Disorder Psychosocial Treatments Systematic reviews of cognitive and behavioral treatments conclude that good clinical outcomes are achieved with Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment (CBT; with and without Motivational Interviewing [MI] Contingency Management (CM) therapies involving the use of reinforcement (Lee and Rawson, 2008). There are questions regarding the durability of treatment effects (especially with respect to CM) Furthermore, the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions is compromised by: Poor rates of treatment induction and retention (Shearer, 2007), Cognitive deficits in executive functioning, particularly those related to inhibitory control, have been hypothesized to potentially render heavily cognitive-based treatments less or ineffective (Baicy and London, 2007 Aharonovich 2008). COCAINE METHAMPHETAMINE (Chan et al., 2019) (Siefried et al. CNS Drugs 2020) 43 randomized controlled trials, 4065 participants, 23 medications; 21 of the studies with 5 medications (Mitrazapine, MPH, Modafinil, Naltrexone, Bupropion) Outcomes and measures varied widely, making it difficult to synthesize the data 55 Primary Outcome measures (most common ones chosen) Abstinence was the most common measure but looked at in MANY ways Reduction in Use Craving Withdrawal When meta-analyses done, often can only do it on a small subset of the studies that share the same outcome measure Adherence- measured by pill count, MEMS, 11 studies did not report adherence. -

Stimulant Use Disorder Treatment Guidance

Stimulant Use Disorder Treatment BSAS recognizes the challenge that stimulant use poses to many individuals, and that care for stimulant use disorders has lagged behind care for other substance use disorders. This practice guidance serves to inform addiction treatment providers across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts of existing tools to implement evidence-informed strategies on the management of stimulant use disorder in program settings. BSAS licensed treatment services are available to people with stimulant use disorders, and ensuring access to quality care is a priority for the Bureau. Table of Contents Key Takeaways 1. Background In the Commonwealth of a. Guidance Rationale Massachusetts there is notable b. Definition of Stimulants concern regarding stimulant use 2. Clinical Care and Support and demand for treatment access. BSAS is committed to equipping a. Stimulant Overdose/Intoxication licensed providers with the skills b. De-escalation and tools to meet this emerging c. Withdrawal Management need. The treatment of stimulant 3. Treatment and Harm Reduction use disorders involves the careful a. Engagement and Retention assessment of patient needs in b. Stimulants and Other Substance Use order to provide a therapeutic environment. Although there are c. Stimulants and Harm Reduction no FDA-approved medications for 4. Special Populations treating stimulant use disorders, a. Co-Occurring Mental and Trauma there are several behavioral b. Stimulants and Pregnancy interventions available and c. Stimulants and Transactional Sex currently implemented by many s. Summary BSAS licensed programs. 6. Relevant Resource 7. Citations Helpline Resources Substance Abuse and Mental Call BSAS' Helpline at l-800-327-5050 Health Services Administration (8 am-70 pm Mon-Fri, 8 am-6 (SAMHSA): Treatment of Stimulant pm on weekends) to get information Use Disorders. -

Association of Cigarette Use and Substance Use Disorders Among US Adults with and Without a Recent Diagnosis of Cancer

Brief Report Association of Cigarette Use and Substance Use Disorders among US Adults with and without a Recent Diagnosis of Cancer Joanna M. Streck 1,2,*, Maria A. Parker 3, Andrea H. Weinberger 4,5, Nancy A. Rigotti 1 and Elyse R. Park 1,2 1 Tobacco Research and Treatment Center, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA; [email protected] (N.A.R.); [email protected] (E.R.P.) 2 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA 3 Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, School of Public Health-Bloomington, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA; [email protected] 4 Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Yeshiva University, Bronx, NY 10461, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Epidemiology & Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10461, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-617-724-6300 (ext. 111-133-0007) Received: 31 October 2020; Accepted: 10 December 2020; Published: 12 December 2020 Abstract: Background: Few studies have examined substance use disorders (SUDs) in cancer patients and it is unclear whether SUDs differentially impact cigarette smoking in patients with vs. without cancer. This study used epidemiological data to estimate current cigarette smoking prevalence and quit ratios among US adults with and without SUDs by cancer status. Methods: Data were drawn from the 2015–2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (n = 170,111). Weighted current smoking prevalence and quit ratios were estimated across survey years by SUDs (with vs. without) and by cancer status (with vs.