Effective Treatments for Methamphetamine Use Disorder: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessation Treatment at Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs

SMOKING CEssATION TREATMENT AT SUBSTANCE ABUSE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS Malcolm S. Reid, PhD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; Jeff Sel- zer, MD, North Shore Long Island Jewish Healthcare System; John Rotrosen, MD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Cigarette smoking is common among persons with drug and alcohol n Nicotine is a highly use disorders, with prevalence rates of 80-90% among patients in sub- addictive substance stance use disorder treatment programs. Such concurrent smoking may that meets all of produce adverse behavioral and medical problems, and is associated the criteria for drug with greater levels of substance use disorder. dependence. CBehavioral studies indicate that the act of cigarette smoking serves as a cue for drug and alcohol craving, and the active ingredient of cigarettes, nicotine, serves as a primer for drug and alcohol abuse (Sees and Clarke, 1993; Reid et al., 1998). More critically, longitudinal studies have found tobacco use to be the number one cause of preventable death in the United States, and also the single highest contributor to mortality in patients treated for alcoholism (Hurt et al., 1996). Nicotine is a highly addictive substance that meets all of the criteria for drug dependence, and cigarette smoking is an especially effective method for the delivery of nicotine, producing peak brain levels within 15-20 seconds. This rapid drug delivery is one of a number of common properties that cigarette smok- ing shares with hazardous drug and alcohol use, such as the ability to activate the dopamine system in the reward circuitry of the brain. -

Treatment of Stimulant Use Disorders

UW PACC Psychiatry and Addictions Case Conference UW Medicine | Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences TREATMENT OF STIMULANT USE DISORDERS Matt Iles-Shih, MD Addiction Psychiatry Fellow University Of Washington & VA Puget Sound Health Care System UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington GENERAL DISCLOSURES The University of Washington School of Medicine also gratefully acknowledges receipt of educational grant support for this activity from the Washington State Legislature through the Safety-Net Hospital Assessment, working to expand access to psychiatric services throughout Washington State. UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington SPEAKER DISCLOSURES No conflicts of interest/disclosures UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington OBJECTIVES 1. Brief overview of stimulant-related physiology & epidemiology 2. Recognizing & treating stimulant use disorders: . Diagnosis & management of acute effects (brief) . Psychotherapies (brief) . Pharmacotherapies 3. Special populations – ADHD in stimulant-abusing pts: to Rx, and how? UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington STIMULANTS: What Substances Are We Talking About? Cocaine Amphetamines: – Prescription Meds – Methamphetamine – Multiple other modified amphetamines MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) [Note: mixed stimulant-psychodelic properties, w/↑serotonin > dopamine and abuse >> addiction.] Others: – Cathinones: Khat & Synthetics (e.g., “Bath Salts”) – Piperazine-like substances (various) – Phenylaklylpyrrolidines (various) UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington COMMONALITIES (WHAT MAKES A STIMULANT -

Gabapentin Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: a Systematic Review

5/26/2017 Gabapentin Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015; 17(5): 10.4088/PCC.15r01821. PMCID: PMC4732322 Published online 2015 Oct 22. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15r01821 Gabapentin Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review Rachel K. Berlin, MD,a Paul M. Butler, MD, PhD,b and Michael D. Perloff, MD, PhDc,* a Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, Massachusetts b Department of Neurology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts c Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston University Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts * Corresponding author: Michael D. Perloff, MD, PhD, Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, 72 E. Concord St, C3, Boston, MA 02118 ([email protected]). Received 2015 Apr 7; Accepted 2015 Jun 12. Copyright © 2015, Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. Abstract Objective: Gabapentin is commonly used offlabel in the treatment of psychiatric disorders with success, failure, and controversy. A systematic review of the literature was performed to elucidate the evidence for clinical benefit of gabapentin in psychiatric disorders. Data sources: Bibliographic reference searches for gabapentin use in psychiatric disorders were performed in PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE search engines with no language restrictions from January 1, 1983, to October 1, 2014, excluding nonhuman studies. For psychiatric references, the keywords bipolar, depression, anxiety, mood, posttraumatic stress disorder (posttraumatic stress disorder and PTSD), obsessivecompulsive disorder (obsessivecompulsive disorder and OCD), alcohol (abuse, dependence, withdraw), drug (abuse, dependence, withdraw), opioid (abuse, dependence, withdraw), cocaine (abuse, dependence, withdraw), and amphetamine (abuse, dependence, withdraw) were crossed with gabapentin OR neurontin. -

Substance Abuse: the Pharmacy Educator’S Role in Prevention and Recovery

Substance Abuse: The Pharmacy Educator’s Role in Prevention and Recovery Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease i Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease1,2 BACKGROUND OF THE CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT In 1988, the AACP Special Interest Group (SIG) on Pharmacy Student and Faculty Impairment (renamed Substance Abuse Education and Assistance) undertook the development of curricular guidelines for colleges/schools of pharmacy to facilitate the growth of educational opportunities for student pharmacists. These Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy Education: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease were published in 1991 (AJPE. 55:311-16. Winter 1991.) One of the charges of the Special Committee on Substance Abuse and Pharmacy Education was to review and revise the 1991 curricular guidelines. Overall, the didactic and experiential components in the suggested curriculum should prepare the student pharmacist to competently problem-solve issues concerning alcohol and other drug abuse and addictive diseases affecting patients, families, colleagues, themselves, and society. The guidelines provide ten educational goals, while describing four major content areas including: psychosocial aspects of alcohol and other drug use; pharmacology and toxicology of abused substances; identification, intervention, and treatment of people with addictive diseases; and legal/ethical issues. The required curriculum suggested by these guidelines addresses the 1 These guidelines were revised by the AACP Special Committee on Substance Abuse and Pharmacy Education. Members drafting the revised guidelines were Edward M. DeSimone (Creighton University), Julie C. Kissack (Harding University), David M. Scott (North Dakota State University), and Brandon J. Patterson (University of Iowa). Other Committee members were Paul W. Jungnickel, Chair (Auburn University), Lisa A. -

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D., M.P.H.; Joseph Guydish, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jill Williams, M.D.; Marc Steinberg, Ph.D.; and Jonathan Foulds, Ph.D. Despite the high prevalence of tobacco use among people with substance use disorders, tobacco dependence is often overlooked in addiction treatment programs. Several studies and a meta-analytic review have concluded that patients who receive tobacco dependence treatment during addiction treatment have better overall substance abuse treatment outcomes compared with those who do not. Barriers that contribute to the lack of attention given to this important problem include staff attitudes about and use of tobacco, lack of adequate staff training to address tobacco use, unfounded fears among treatment staff and administration regarding tobacco policies, and limited tobacco dependence treatment resources. Specific clinical-, program-, and system-level changes are recommended to fully address the problem of tobacco use among alcohol and other drug abuse patients. KEY WORDS: Alcohol and tobacco; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use, abuse, dependence; addiction care; tobacco dependence; smoking; secondhand smoke; nicotine; nicotine replacement; tobacco dependence screening; tobacco dependence treatment; treatment facility-based prevention; co-treatment; treatment issues; treatment barriers; treatment provider characteristics; treatment staff; staff training; AODD counselor; client counselor interaction; smoking cessation; Tobacco Dependence Program at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey obacco dependence is one of to the other. The common genetic vul stance use was considered a potential the most common substance use nerability may be located on chromo trigger for the primary addiction. -

Vol. 1, Issue 1

Methamphetamine Topical Brief Series: Vol. 1, Issue 1 What is countries involved in World War II provided amphetamine to soldiers Methamphetamine? for performance enhancement and the drug was used by “actors, artists, Methamphetamine is an addictive, athletes, politicians, and the public stimulant drug that affects the alike.”5 central nervous system. It is typically used in powder or pill form and can By the 1960s, media coverage be ingested orally, snorted, smoked, began drawing simplistic, negative or injected. Methamphetamine is connections between amphetamine known as meth, blue, ice, speed, and and crime, and government officials 1 crystal among other names. The term discussed public safety and drugs amphetamine has been used broadly as a social concern.6 Over-the- to refer to a group of chemicals that counter amphetamines were have similar, stimulating properties available until 1959,7 and by 1970 and methamphetamine is included in all amphetamines were added to 2 this group. According to the National the controlled substances list as Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Schedule II drugs. Schedule II drugs “Methamphetamine differs from required a new prescription with amphetamine in that, at comparable each fill and strict documentation doses, much greater amounts of the by doctors and pharmacists.8 drug get into the brain, making it a The reduction in a legal supply 3 more potent stimulant.” of amphetamine led to increased black-market production and sale From the 1930s to the 1960s, of various types of amphetamine U.S. pharmaceutical -

Cocaine Use Disorder

COCAINE USE DISORDER ABSTRACT Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem. Millions of Americans regularly use cocaine, and some develop a substance use disorder. Cocaine is generally not ingested, but toxicity and death from gastrointestinal absorption has been known to occur. Medications that have been used as substitution therapy for the treatment of a cocaine use disorder include amphetamine, bupropion, methylphenidate, and modafinil. While pharmacological interventions can be effective, a recent review of pharmacological therapy for cocaine use indicates that psycho-social efforts are more consistent over medication as a treatment option. Introduction Cocaine is an illicit, addictive drug that is widely used. Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem that burdens the healthcare system and that can be destructive to individual lives. It is impossible to know with certainty the extent of use but data from public health surveys, morbidity and mortality reports, and healthcare facilities show that there are millions of Americans who regularly take cocaine. Cocaine intoxication is a common cause for emergency room visits, and it is one drug that is most often involved in fatal overdoses. Some cocaine users take the drug occasionally and sporadically but as with every illicit drug there is a percentage of people who develop a substance use disorder. Treatment of a cocaine use disorder involves psycho-social interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com Pharmacology of Cocaine Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the Erthroxylum coca plant, a plant that is indigenous to South America and several other parts of the world, and is cultivated elsewhere. -

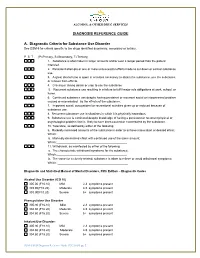

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Drug Use and Gender

Drug Use and Gender Tammy L. Anderson, Ph.D. University of lllinois, Chicago, lL GENDER DIFFERENCES IN study-report a greater occurrence ofillicit substance use DRUG USE AND ABUSE among males than among females. Both surveys have consistently documented this pattern over the years. Looking at the world through a "gender lens" began According to the 1997 NHSDA survey, men reported a in most areas of social science during the second wave of higher rate of illicit substance use (any illicit drug) than the women's movement, or the late 1960s through the women, 8.5 percent to 4.5 percent, nearly double. Men 1970s. During this time feminist researchers began report higher rates of cocaine use .9 percent versus .5 questioning science's conclusions by pointing to percent. alcohol use (58 percent versus 45 percent), binge male-oriented biases in research questions, hypotheses, drinking (23 percent versus 8 percent), and heavy drinking and designs. (8.7 percent versus 2.1 percent). The same pattern was Unfortunately, the "gender lens" did not appear in observed in marijuana use (Office of Applied Studies substance use research until the early 1980s. Prior to the [OAS] tee7). 1970s, most studies of alcohol and other drug use were Johnston. O'Malley, and Bachman (1997) the conducted among males. Early studies that included at University of Michigan yearly women suffered from the "add women and stir compile data on the substance use of 8th. 10th, and 12th graders, college students, approach." Females were added to samples, but no and young adults in the MTF study. -

Pharmacotherapy for Methamphetamine/Amphetamine Use Disorder—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

REVIEW doi:10.1111/add.14755 Pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine/amphetamine use disorder—a systematic review and meta-analysis Brian Chan1,2, Michele Freeman3 , Karli Kondo3, Chelsea Ayers3, Jessica Montgomery3, Robin Paynter3 & Devan Kansagara1,3,4 Division of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA,1 Central City Concern, Portland, OR, USA,2 Evidence- based Synthesis Program Center, VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, USA3 and Department of Medicine, VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, OR, USA4 ABSTRACT Aims Addiction to methamphetamine/amphetamine (MA/A) is a major public health problem. Currently there are no pharmacotherapies for MA/A use disorder that have been approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency. We reviewed the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for MA/A use disorder to assess the qual- ity, publication bias and overall strength of the evidence. Methods Systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched multiple data sources (MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library) to April 2019 for systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Included studies recruited adults who had MA/A use disorder; sample sizes ranged from 19 to 229 participants. Outcomes of interest were abstinence, defined as 3 or more consecutive weeks with negative urine drug screens (UDS); overall use, analyzed as the proportion of MA/A negative UDS specimens; and treatment reten- tion. One SR of pharmacotherapies for MA/A use disorder and 17 additional RCTs met our inclusion criteria encompassing 17 different drugs (antidepressants, antipsychotics, psychostimulants, anticonvulsants and opioid antagonists). We combined the findings of trials with comparable interventions and outcome measures in random-effects meta-analyses. -

Meth/Amphetamine Use and Associated HIV: Implications for Global Policy and Public Health

International Journal of Drug Policy 21 (2010) 347–358 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Review Meth/amphetamine use and associated HIV: Implications for global policy and public health Louisa Degenhardt ∗,1, Bradley Mathers 2, Mauro Guarinieri 3, Samiran Panda 4, Benjamin Phillips 5, Steffanie A. Strathdee 6, Mark Tyndall 7, Lucas Wiessing 8, Alex Wodak 9, John Howard 10, the Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and injecting drug use National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia article info abstract Article history: Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) have become the focus of increasing attention worldwide. There are Received 29 May 2009 understandable concerns over potential harms including the transmission of HIV. However, there have Received in revised form 30 October 2009 been no previous global reviews of the extent to which these drugs are injected or levels of HIV among Accepted 24 November 2009 users. A comprehensive search of the international peer-reviewed and grey literature was undertaken. Multiple electronic databases were searched and documents and datasets were provided by UN agencies and key experts from around the world in response to requests for information on the epidemiology of use. Keywords: Amphetamine or methamphetamine (meth/amphetamine, M/A) use was documented in 110 countries, Methamphetamine Amphetamine and injection in 60 of those. Use may be more prevalent in East and South East Asia, North America, South HIV Africa, New Zealand, Australia and a number of European countries. In countries where the crystalline Injecting form is available, evidence suggests users are more likely to smoke or inject the drug; in such countries, Epidemiology higher levels of dependence may be occurring. -

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Pharmacological Management of Substance Abuse, Harmful Use, Addictio

444324 JOP0010.1177/0269881112444324Lingford-Hughes et al.Journal of Psychopharmacology 2012 BAP Guidelines BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, Journal of Psychopharmacology 0(0) 1 –54 harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav recommendations from BAP DOI: 10.1177/0269881112444324 jop.sagepub.com AR Lingford-Hughes1, S Welch2, L Peters3 and DJ Nutt 1 With expert reviewers (in alphabetical order): Ball D, Buntwal N, Chick J, Crome I, Daly C, Dar K, Day E, Duka T, Finch E, Law F, Marshall EJ, Munafo M, Myles J, Porter S, Raistrick D, Reed LJ, Reid A, Sell L, Sinclair J, Tyrer P, West R, Williams T, Winstock A Abstract The British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines for the treatment of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity with psychiatric disorders primarily focus on their pharmacological management. They are based explicitly on the available evidence and presented as recommendations to aid clinical decision making for practitioners alongside a detailed review of the evidence. A consensus meeting, involving experts in the treatment of these disorders, reviewed key areas and considered the strength of the evidence and clinical implications. The guidelines were drawn up after feedback from participants. The guidelines primarily cover the pharmacological management of withdrawal, short- and long-term substitution, maintenance of abstinence and prevention of complications, where appropriate, for substance abuse or harmful use or addiction as well management in pregnancy, comorbidity with psychiatric disorders and in younger and older people. Keywords Substance misuse, addiction, guidelines, pharmacotherapy, comorbidity Introduction guidelines (e.g.