Stimulant Use Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatment of Stimulant Use Disorders

UW PACC Psychiatry and Addictions Case Conference UW Medicine | Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences TREATMENT OF STIMULANT USE DISORDERS Matt Iles-Shih, MD Addiction Psychiatry Fellow University Of Washington & VA Puget Sound Health Care System UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington GENERAL DISCLOSURES The University of Washington School of Medicine also gratefully acknowledges receipt of educational grant support for this activity from the Washington State Legislature through the Safety-Net Hospital Assessment, working to expand access to psychiatric services throughout Washington State. UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington SPEAKER DISCLOSURES No conflicts of interest/disclosures UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington OBJECTIVES 1. Brief overview of stimulant-related physiology & epidemiology 2. Recognizing & treating stimulant use disorders: . Diagnosis & management of acute effects (brief) . Psychotherapies (brief) . Pharmacotherapies 3. Special populations – ADHD in stimulant-abusing pts: to Rx, and how? UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington STIMULANTS: What Substances Are We Talking About? Cocaine Amphetamines: – Prescription Meds – Methamphetamine – Multiple other modified amphetamines MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) [Note: mixed stimulant-psychodelic properties, w/↑serotonin > dopamine and abuse >> addiction.] Others: – Cathinones: Khat & Synthetics (e.g., “Bath Salts”) – Piperazine-like substances (various) – Phenylaklylpyrrolidines (various) UW PACC ©2017 University of Washington COMMONALITIES (WHAT MAKES A STIMULANT -

Empirical Evidence for Definitions of Episode, Remission, Recovery, Relapse and Recurrence in Depression: a Systematic Review

Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences (2019), 28, 544–562. © Cambridge University Press 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1017/S2045796018000227 Empirical evidence for definitions of episode, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence in depression: a systematic review P. L. de Zwart1*, B. F. Jeronimus1,2 and P. de Jonge1,2 1 University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Psychiatry, Interdisciplinary Center Psychopathology and Emotion Regulation (ICPE), Groningen, The Netherlands 2 University of Groningen, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences, Department of Developmental Psychology, Groningen, The Netherlands Aims. For the past quarter of a century, Frank et al.’s (1991) consensus-based definitions of major depressive disorder (MDD) episode, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence have been the paramount driving forces for consistency in MDD research as well as in clinical practice. This study aims to review the evidence for the empirical validation of Frank et al.’s proposed concept definitions and to discuss evidence-based modifications. Methods. A literature search of Web of Science and PubMed from 1/1/1991 to 08/30/2017 identified all publications which referenced Frank et al.’s request for definition validation. Publications with data relevant for validation were included and checked for referencing other studies providing such data. Results. A total of 56 studies involving 39 315 subjects were included, mainly presenting data to validate the severity and duration thresholds for defining remission and recovery. Most studies indicated that the severity threshold for defining remission should decrease. Additionally, specific duration thresholds to separate remission from recovery did not add any predictive value to the notion that increased remission duration alleviates the risk of reoccurrence of depressive symp- toms. -

Impact of Disclosure of Relapse for Self-Identified Sexual Addicts

Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20:157–170, 2013 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1072-0162 print / 1532-5318 online DOI: 10.1080/10720162.2013.786659 ARTICLES Impact of Disclosure of Relapse for Self-Identified Sexual Addicts M. DEBORAH CORLEY Sante´ Center for Healing, Argyle, Texas SARA E. POLLARD and JOSHUA N. HOOK University of North Texas, Denton, Texas JENNIFER P. SCHNEIDER Tucson, Arizona Disclosure as a process of both recovery and healing within commit- ted relationships is advocated by couple and addiction therapists. The traumatic impact for partners of an initial disclosure or discov- ery of betrayals has been well documented, but less is known about the impact of disclosure for sex addicts. The present study explored the experience of relapse and disclosure among sex addicts. Relapse was a common experience among sex addicts, and the disclosure of relapse had a range of consequences for the addict and the re- lationship. Voluntary disclosure of relapse (rather than the partner discovering relapses independently) was associated with positive relational outcomes. The majority of sexual behaviors engaged in by sexual addicts who are in a committed relationship are considered a violation of trust by their partners (Bird, Butler, & Fife, 2007; Kalichman & Cain, 2004; Young, Griffin-Shelley, Cooper, O’Mara, & Buchanan, 2000). This violation is also considered a betrayal and may be described as a secret sexual, romantic, or emotional involvement that violates the rules of and commitment to an exclusive re- lationship (Glass, 2002; Laaser, 2011; Whisman & Wagers, 2005). The most significant betrayals are those associated with repeated secrets, lies, decep- tions, and broken promises (Corley & Schneider, 2002; Corley, Schneider, Thanks to Dr. -

Alcohol Use Disorder Relapse Factors a Systematic Review

Psychiatry Research 278 (2019) 97–115 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Psychiatry Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/psychres Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review T ⁎ Wilco Sliedrechta, , Ranne de Waartb, Katie Witkiewitzc, Hendrik G. Roozend a De Hoop GGZ, Provincialeweg 70, 3329 KP Dordrecht, the Netherlands b Mentrum/Arkin, Wisselwerking 46-48, 1112 XR Diemen, the Netherlands c The University of New Mexico (UNM), MSC 03-2220, Univ of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA d The University of New Mexico (UNM), Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions (CASAA), MSC 11 6280, 1 Univ of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: A relapsing-remitting course is very common in patients with an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). Understanding the Remittance determinants associated with alcohol resumption remains a formidable task. This paper examines relapse de- Recurrence terminants based on a systematic review of recent alcohol literature (2000–2019). Relevant databases were Relapse determinants consulted for articles that contained information about specific relapse determinants and reported statistical Dual diagnosis significance of each relapse determinant in predicting relapse. Relapse was broadly defined based on the Biopsychosocial model characterization in the included articles. From the initial identified 4613 papers, a total of 321 articles were Spiritual included. Results encompass multiple relapse determinants, which were ordered according to biopsychosocial and spiritual categories, and presented, using a descriptive methodology. Psychiatric co-morbidity, AUD se- verity, craving, use of other substances, health and social factors were consistently significantly associated with AUD relapse. Conversely, supportive social network factors, self efficacy, and factors related to purpose and meaning in life, were protective against AUD relapse. -

Cocaine Use Disorder

COCAINE USE DISORDER ABSTRACT Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem. Millions of Americans regularly use cocaine, and some develop a substance use disorder. Cocaine is generally not ingested, but toxicity and death from gastrointestinal absorption has been known to occur. Medications that have been used as substitution therapy for the treatment of a cocaine use disorder include amphetamine, bupropion, methylphenidate, and modafinil. While pharmacological interventions can be effective, a recent review of pharmacological therapy for cocaine use indicates that psycho-social efforts are more consistent over medication as a treatment option. Introduction Cocaine is an illicit, addictive drug that is widely used. Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem that burdens the healthcare system and that can be destructive to individual lives. It is impossible to know with certainty the extent of use but data from public health surveys, morbidity and mortality reports, and healthcare facilities show that there are millions of Americans who regularly take cocaine. Cocaine intoxication is a common cause for emergency room visits, and it is one drug that is most often involved in fatal overdoses. Some cocaine users take the drug occasionally and sporadically but as with every illicit drug there is a percentage of people who develop a substance use disorder. Treatment of a cocaine use disorder involves psycho-social interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com Pharmacology of Cocaine Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the Erthroxylum coca plant, a plant that is indigenous to South America and several other parts of the world, and is cultivated elsewhere. -

Predicting Relapse to Alcohol and Drug Abuse Via Quantitative Electroencephalography Lance O

Predicting Relapse to Alcohol and Drug Abuse via Quantitative Electroencephalography Lance O. Bauer, Ph.D. A sensitive and specific screening test that would identify abstinence and 22 additional subjects with no history of the subset of substance-abusing patients at highest risk for substance dependence. Importantly, in subsequent logistic relapse would constitute an important advance for treatment regression analyses, fast  power was found to be superior to planning. This study examined the relative value of severity of illness, depression level, and childhood conduct quantitative electroencephalography as a rapid, inexpensive, problems in predicting relapse. With fast  power as the sole and noninvasive measure of relapse potential. The subjects predictor, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and were 107 substance-dependent patients enrolled in negative predictive value parameters for discriminating residential treatment programs. All were unmedicated and outcomes were 0.61, 0.85, 0.75, and 0.74, respectively. free of the complicating effects of major medical and Additional ANCOVAs revealed that the EEG difference neurological disorders. Structured clinical interview data between relapse-prone and abstinence-prone groups was and a 5-minute recording of the resting, eyes-closed related to the interaction of two premorbid factors, viz., electroencephalogram were obtained after patients had childhood Conduct Disorder and paternal alcoholism. The verifiably maintained abstinence for 1–5 months. Patients enhancement of fast  electroencephalographic activity in were then monitored for relapse or successful abstinence by patients who will later relapse most likely originates from a research staff for an ensuing 6-month period. ANCOVAs of premorbid and subtle dysfunction involving frontal brain EEG power spectral density within pre-defined frequency regions. -

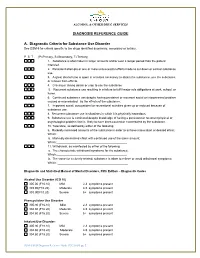

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Getting Through Amphetamine Withdrawal – a Guide for People

Amphetamine_wdl_220404.qxd 28/04/2004 12:19 PM Page i GETTING THROUGH AMPHETAMINE WITHDRAWAL A guide for people trying to stop amphetamine use Amphetamine_wdl_220404.qxd 28/04/2004 12:19 PM Page ii GETTING THROUGH AMPHETAMINE WITHDRAWAL CONTENTS About this book x Making the decision to stop using amphetamines x Amphetamine withdrawal x What is withdrawal? x How long will the symptoms last? What kinds of symptoms will I have? x Getting started x Organise a safe environment x Organise support x Structure your day x The role of medication x Getting through withdrawal x Cravings x Sleep x September 1996 Relaxing x Revised May 2004 Mood swings x © Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre Inc. Strange thoughts x 54-62 Gertrude Street, Fitzroy VIC 3065 Eating again x T: 03 8413 8413 Aches and pains x F: 03 9416 3420 High-risk situations x Counselling x E: [email protected] It’s all too much x www.turningpoint.org.au Sex and withdrawal x Original edition by Dr Nik Lintzeris, Dr Adrian Dunlop and After withdrawal x David Thornton What next? x Updated (2004) by Dr Adrian Dunlop, Sandra Hocking, Dr Getting back on track if you ‘slip up’ x Nicole Lee and Peter Muhleisen Notes for supporters x Cartoonist: Mal Doreian Useful contact numbers x ISBN 0_958 6979_1_4 1 Amphetamine_wdl_220404.qxd 28/04/2004 12:19 PM Page 2 GETTING THROUGH AMPHETAMINE WITHDRAWAL MAKING THE DECISION TO STOP USING AMPHEATMINES ABOUT THIS BOOK This book is written for people who are thinking about You may find it helpful to make a list of the positives and the or trying to stop using amphetamines, even if just for a negatives about using amphetamines. -

The Addictive Potential of Sexual Behavior (Impulse) Review2

Page 1 of 9 Impulse: The Premier Journal for Undergraduate Publications in the Neurosciences Submitted for Publication January, 2018 The Addictive Potential of Sexual Behavior Heather Bool D’Youville College, Buffalo, New York This paper examines the addictive potential of sexual behavior through behavioral and neurophysiological mechanisms analogous to other formalized addictions. Sexual behavior refers to any action or thought preformed with the intention of sexual gratification, such as the consumption of explicit material, masturbation, fantasizing of sexual scenarios, and sexual intercourse. Addiction is defined by the presence of tolerance, preoccupation, withdrawal, dependence, and the continuation of behavior despite risk and/or harm. Sexual addiction demonstrates high relapse potential due to the frequency of reward-associated cues encountered in daily life, and the low effort and risk required for sexual pleasure. Currently, sexual addiction lacks a formal diagnosis despite behavioral, psychological, and physiological evidence. An official diagnosis recognized by a governing authority, such as the American Psychological Association, would offer greater access to treatment, funding for research, and exposure and education for the general public about this disorder. Abbreviations: None Keywords: Sexual Behavior; Addiction; Sexual Addiction; Neurophysiology; Behavioral Neuroscience Introduction “Sexual addiction” is an umbrella term Confusion remains regarding the for sexual impulsivity, sexual compulsivity, out- etiology and nosology of sexual addiction, of-control sexual behavior, hypersexual which has led to the lack of a universally behavior or disorder, sexually excessive accepted criterion and, more importantly, the behavior or disorder, Don Jaunism, satyriasis, absence of a formal diagnosis. A lack of and obsessive-compulsive sexual behavior operationalization of the disorder has severe (Beech et al., 2009; Karila et al., 2014; effects on research; due to the use of Rosenberg et al., 2014). -

“How Can I Prepare for My Husband's Next Porn Relapse?”

BLOG “How Can I Prepare for My Husband’s Next Porn Relapse?” ONCE UPON A TIME, I WAS BLISSFULLY HAPPY. No, my life wasn’t perfect or easy. Instead, it was real. Messy, but meaningful. I lived and worked passionately within the world of pornography addiction and betrayal trauma recovery, with a job I adored and the marriage I’d always wanted. And then, without warning, it all came crashing down. MY STORY IS A BIT UNUSUAL. The incident I’m describing didn’t occur at the start of our recovery from my husband’s porn addiction, it happened after nearly a decade of intensive “his, hers, and ours” recovery work. I’d thought that, surely, the worst was behind us. I believed I was one of a lucky few whose husband grasped the make-or-break importance of staying sexually sober, who understood the imperative of gut-level honesty. I trusted my husband deeply (not entirely, but significantly), and I thanked God every day for giving me the most empathetic pornography addict I’d ever met. Relapse And then, out of the blue, my husband disclosed a porn relapse that knocked me to my knees. There I sat. Unknowing. Unraveled. Disbelieving. Disoriented. I felt an entire dictionary of adverbs and adjectives, dizzy I do believe (emphatically) that relapse prevention matters. with a cyclone of fractured vocabulary. And yet, despite that But as I don’t possess the formula for making it happen, flood of emotion and experience, I can identify, with razor I lobby instead for the next best thing: I work to ensure precision, the one single word that embodies that horrific that my clients are well prepared for the possibility of their day: unprepared. -

DSM-5 Diagnoses and New ICD-10-CM Codes

DSM-5 DiAgnoses And New ICD-10-CM Codes As Ordered in the DSM-5 Classification DSM-5 Recommended DSM-5 Recommended Disorder ICD-10-CM Code for use ICD-10-CM Code for use through September 30, 2017 beginning October 1, 2017 Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder F50.89 F50.82 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild F10.10 F10.10 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained remission F10.10 F10.11 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild F12.10 F12.10 Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F12.10 F12.11 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F16.10 F16.11 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or F16.20 F16.21 sustained remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F16.20 F16.21 remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild, In early or F16.10 F16.11 sustained remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, -

Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction. Manual 1

i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The development of earlier versions of this manual was supported by several research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The current manual was written by Dr. Kathleen Carroll of Yale University under Contract Number N-OIDA-4-2205 with the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Lisa Onken, the NIDA Project Officer, offered valuable guidance and comments throughout the preparation of this manual. The material presented in this manual is the result of a program of research by Dr. Kathleen Carroll and Dr. Bruce Rounsaville and their colleagues at Yale University. The development of this therapy model for treatment of drug abuse drew extensively from the work of Alan Marlatt and others (Marlatt and Gordon 1985; Chancy et al. 1978; Jaffe et al. 1988; Ito et al. 1984). The structure and sequence of sessions presented in this therapy model was partially developed by work on Project MATCH published by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Kadden et al. 1992) and the manual developed by Peter Monti and his colleagues (1989). These sources are particularly reflected here in the a skills-training material, and we have acknowledged the original sources in each of those sections. Yale University Research Team Coinvestigators: Bruce Rounsaville, M.D. Roseann Bisighini, M.S. Charla Nich, M.S. Monica Canning-Ball Sam Ball, Ph.D. Joanne Corvino, M.P.H. Lisa Fenton, Psy.D. Kea Cox Frank Gawin, M.D. Lynn Gordon, R.N. Tom Kosten, M.D. Tami Frankforter Elinor McCance-Katz, M.D., Ph.D. jenniffer Owler Douglas Ziedonis, M.D.