War in Mali. Background Study and Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Operation Serval to Barkhane

same year, Hollande sent French troops to From Operation Serval the Central African Republic (CAR) to curb ethno-religious warfare. During a visit to to Barkhane three African nations in the summer of 2014, the French president announced Understanding France’s Operation Barkhane, a reorganization of Increased Involvement in troops in the region into a counter-terrorism Africa in the Context of force of 3,000 soldiers. In light of this, what is one to make Françafrique and Post- of Hollande’s promise to break with colonialism tradition concerning France’s African policy? To what extent has he actively Carmen Cuesta Roca pursued the fulfillment of this promise, and does continued French involvement in Africa constitute success or failure in this rançois Hollande did not enter office regard? France has a complex relationship amid expectations that he would with Africa, and these ties cannot be easily become a foreign policy president. F cut. This paper does not seek to provide a His 2012 presidential campaign carefully critique of President Hollande’s policy focused on domestic issues. Much like toward France’s former African colonies. Nicolas Sarkozy and many of his Rather, it uses the current president’s predecessors, Hollande had declared, “I will decisions and behavior to explain why break away from Françafrique by proposing a France will not be able to distance itself relationship based on equality, trust, and 1 from its former colonies anytime soon. solidarity.” After his election on May 6, It is first necessary to outline a brief 2012, Hollande took steps to fulfill this history of France’s involvement in Africa, promise. -

Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand

ICIP WORKING PAPERS: 2010/01 GRAN VIA DE LES CORTS CATALANES 658, BAIX 08010 BARCELONA (SPAIN) Territorial Autonomy T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | WWW.ICIP.CAT and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Institut Català Internacional per la Pau Barcelona, April 2010 Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, 658, baix. 08010 Barcelona (Spain) T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | http:// www.icip.cat Editors Javier Alcalde and Rafael Grasa Editorial Board Pablo Aguiar, Alfons Barceló, Catherine Charrett, Gema Collantes, Caterina Garcia, Abel Escribà, Vicenç Fisas, Tica Font, Antoni Pigrau, Xavier Pons, Alejandro Pozo, Mònica Sabata, Jaume Saura, Antoni Segura and Josep Maria Terricabras Graphic Design Fundació Tam-Tam ISSN 2013-5793 (online edition) 2013-5785 (paper edition) DL B-38.039-2009 © 2009 Institut Català Internacional per la Pau · All rights reserved T H E A U T HOR Roger Suso holds a B.A. in Political Science (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, UAB) and a M.A. in Peace and Conflict Studies (Uppsa- la University). He gained work and research experience in various or- ganizations like the UNDP-Lebanon in Beirut, the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin, the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights to the Maghreb Elcàlam in Barcelona, and as an assist- ant lecturer at the UAB. An earlier version of this Working Paper was previously submitted in May 20, 2009 as a Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Swe- den, under the supervisor of Thomas Ohlson. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10

Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10 New Responses to Africa’s Mass Atrocities By John Prendergast April 2014 WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10 New Responses to Africa’s Mass Atrocities* By John Prendergast April 2014 COVER PHOTO A young Rwandan girl walks through Nyaza cemetery outside Kigali, Rwanda on Monday November 25, 1996. Thousands of victims of the 1994 genocide are buried there. AP/RICARDO MAZALAN * This Enough Project report expands on an earlier argument advanced in a Foreign Affairs article entitled “The New Face of African Conflict: In Search of a Way Forward,” by John Prendergast, published March 12, 2014. Introduction As commemorations unfold honoring the 20th anniversary of the onset of Rwanda’s genocide and the 10th year after Darfur’s genocide was recognized, the rhetoric of commitment to the prevention of mass atrocities has never been stronger. Actions, unsurprisingly, have not matched that rhetoric. But the conventional diagnosis of this chasm between words and deeds – a lack of political will – only explains part of the action deficit. More deeply, international crisis response strategies in Africa have hardly evolved in the years since the Rwandan genocide erupted. Until there is a fuller recognition of the core drivers of African conflict, their cross-border nature, and the need for more nuanced and comprehensive responses, the likelihood will remain high that more and more anniversaries of mass atrocity events will have to be commemorated by future generations. Conflict drivers need to be much better understood in order to devise more relevant responses. The band of crisis and conflict spanning the Horn of Africa, East Africa, and Central Africa is ground zero for mass atrocity events globally. -

Enjeux Spatiaux Et Fonciers Dans Le Delta Intérieur Du Niger (Mali) : Delmasig, Un SIG À Vocation Locale Et Régionale

tnjeux spatiaux et fonciers dans le delta intérieur du Niger (Mali) Delmasig, un SIG à vocation locale et régionale Jérôme Marie Géographe Le présent article expose brièvement quelques-uns des résultats obtenus par l'utilisation du SIG Delmasig concernant l'évolution des rizières et les relations entre espace rizicole et espace pastoral. Ce système d'information géographique est dédié à l'aide à la décision pour une gestion régionale et locale des hommes, des milieux, des enjeux spatiaux et fonciers dans le delta intérieur amont du fleuve Niger au Mali (Marie, 2000). L'espace traité couvre les plaines de la cuvette du Niger depuis, en amont, Ké- Macina sur le Niger et Baramandougou sur le Bani, jusqu'au lac Débo en aval, y compris une fraction du Farimaké au nord-ouest du lac Débo, soit une superficie totale légèrement supérieure à 22 000 km2. Les données portent sur : - les formations végétales et leur relation avec la crue, dont dérive une modélisation des surfaces inondées ; -une analyse de l'évolution des surfaces cultivées en riz entre 1952, 1975 et 1989 : la comparaison diachronique de l'emprise des cultures de riz à ces trois dates permet d'en retracer l'évolution sur une quarantaine d'années, tandis que la comparaison de l'emprise des rizières avec les formations végétales permet de mettre en 558 T Gestion intégrée des zones inondables tropicales évidence les stratégies des riziculteurs et de suivre plus particulièrement l'évolution de l'espace « des crues utiles » année par année ; -une modélisation des nouveaux cadres territoriaux -

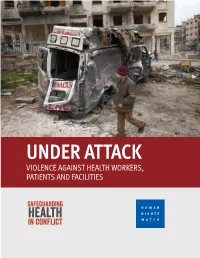

Under Attack

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

Operation Serval. Analyzing the French Strategy Against Jihadists in Mali

ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2015 Operation Serval Analyzing the French Strategy against Jihadists in Mali LT COL STÉPHANE SPET, FRENCH AIR FORCE* imilar to the events that occurred two years earlier in Benghazi, the crews of the four Mirage 2000Ds that took off on the evening of 11 January 2013 from Chad inbound for Kona in central Mali knew that they were about to conduct a mis- sion that needed to stop the jihadist offensive to secure Bamako, the capital of Mali, and its population. This time, they were not alone because French special forces Swere already on the battlefield, ready to bring their firepower to bear. French military forces intended to prevent jihadist fighters from creating a caliphate in Mali. They also knew that suppressing any jihadist activity there would be another challenge—a more political one intended to remove the arrows from the jihadists’ hands. By answering the call for assistance from the Malian president to prevent jihadists from raiding Bamako and creating a radical Islamist state, French president François Hollande consented to engage his country in the Sahel to fight jihadists. Within a week, Operation Serval had put together a joint force that stopped the jihadist offensive and retook the initiative. Within two months, the French-led coalition had liberated the en- tire Malian territory after destruction of jihadist strongholds in the Adrar des Ifoghas by displaying a strategy that surprised both the coalition’s enemies and its allies. On 31 July 2014, this first chapter of the war on terror in the Sahel officially closed with a victory and the attainment of all objectives at that time. -

If Our Men Won't Fight, We Will"

“If our men won’t ourmen won’t “If This study is a gender based confl ict analysis of the armed con- fl ict in northern Mali. It consists of interviews with people in Mali, at both the national and local level. The overwhelming result is that its respondents are in unanimous agreement that the root fi causes of the violent confl ict in Mali are marginalization, discrimi- ght, wewill” nation and an absent government. A fact that has been exploited by the violent Islamists, through their provision of services such as health care and employment. Islamist groups have also gained support from local populations in situations of pervasive vio- lence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and they have offered to restore security in exchange for local support. Marginality serves as a place of resistance for many groups, also northern women since many of them have grievances that are linked to their limited access to public services and human rights. For these women, marginality is a site of resistance that moti- vates them to mobilise men to take up arms against an unwilling government. “If our men won’t fi ght, we will” A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Confl ict in Northern Mali Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad FOI-R--4121--SE ISSN1650-1942 November 2015 www.foi.se Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad "If our men won't fight, we will" A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Conflict in Northern Mali Bild/Cover: (Helené Lackenbauer) Titel ”If our men won’t fight, we will” Title “Om våra män inte vill strida gör vi det” Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4121—SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 77 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikes- & Försvarsdepartementen Forskningsområde 8. -

AQIM's Blueprint for Securing Control of Northern Mali

APRIL 2014 . VOL 7 . ISSUE 4 Contents Guns, Money and Prayers: FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Guns, Money and Prayers: AQIM’s Blueprint for Securing AQIM’s Blueprint for Securing Control of Northern Mali By Morten Bøås Control of Northern Mali By Morten Bøås REPORTS 6 AQIM’s Threat to Western Interests in the Sahel By Samuel L. Aronson 10 The Saudi Foreign Fighter Presence in Syria By Aaron Y. Zelin 14 Mexico’s Vigilante Militias Rout the Knights Templar Drug Cartel By Ioan Grillo 18 Drug Trafficking, Terrorism, and Civilian Self-Defense in Peru By Steven T. Zech 23 Maritime Piracy on the Rise in West Africa By Stephen Starr 26 Recent Highlights in Political Violence 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts An Islamist policeman patrolling the streets of Gao in northern Mali on July 16, 2012. - Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images l-qa`ida in the islamic As a result, even if the recent French Maghreb (AQIM) is military intervention in Mali has occasionally described as pushed back the Islamist rebels and an operational branch of the secured control of the northern cities of Aglobal al-Qa`ida structure. Yet AQIM Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu, a number of should not be viewed as an external al- challenges remain.1 The Islamists have Qa`ida force operating in the Sahel and not been defeated. Apart from the loss of Sahara. For years, AQIM and its offshoots prominent figures such as AQIM senior About the CTC Sentinel have pursued strategies of integration leader Abou Zeid and the reported death The Combating Terrorism Center is an in the region based on a sophisticated of Oumar Ould Hamaha,2 the rest of the independent educational and research reading of the local context. -

Bibliography: Boko Haram

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 3 Bibliography: Boko Haram Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes [Bibliographic Series of Perspectives on Terrorism – BSPT-JT-2019-5] Abstract This bibliography contains journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, grey literature, bibliog- raphies and other resources on the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram. While focusing on recent literature, the bibliography is not restricted to a particular time period and covers publications up to May 2019. The literature has been retrieved by manually browsing more than 200 core and periphery sources in the field of Terrorism Stud- ies. Additionally, full-text and reference retrieval systems have been employed to broaden the search. Keywords: bibliography, resources, literature, Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province, ISWAP, Abu- bakar Shekau, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, Nigeria, Lake Chad region NB: All websites were last visited on 18.05.2019. - See also Note for the Reader at the end of this literature list. Bibliographies and other Resources Benkirane, Reda et al. (2015-): Radicalisation, violence et (in)sécurité au Sahel. URL: https://sahelradical.hy- potheses.org Bokostan (2013, February-): @BokoWatch. URL: https://twitter.com/BokoWatch Campbell, John (2019, March 1-): Nigeria Security Tracker. URL: https://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-securi- ty-tracker/p29483 Counter Extremism Project (CEP) (n.d.-): Boko Haram. (Report). URL: https://www.counterextremism.com/ threat/boko-haram Elden, Stuart (2014, June): Boko Haram – An Annotated Bibliography. Progressive Geographies. URL: https:// progressivegeographies.com/resources/boko-haram-an-annotated-bibliography Hoffendahl, Christine (2014, December): Auf der Suche nach einer Strategie gegen Boko Haram. [In search for a strategy against Boko Haram]. -

Mali's Political Crisis and Its International Implications

BULLETIN No. 53 (386) May 22, 2012 © PISM Editors: Marcin Zaborowski (Editor-in-Chief), Katarzyna Staniewska (Executive Editor), Jarosław Ćwiek-Karpowicz, Beata Górka-Winter, Artur Gradziuk, Beata Wojna Mali’s Political Crisis and Its International Implications Kacper Rękawek Civil war and a coup d’état in Mali constitute a serious threat to the stability of Western Africa, a region bordering the “Arab Spring”-engulfed Northern Africa. The European Union should support African efforts aimed at resolving the crisis, and condition future aid for Mali on the results of political mediation organised by the country’s neighbours who are aiming to restore the country back to civilian rule. Mali is a Western African state inhabited by fourteen and a half million people. Up to 65% of Mali’s area is desert and it is one of the poorest countries in the world. However, during the last 20 years it had become a regional leader in democratic transition. The Tuareg Rebellion in Mali. Ten percent of Malians living in the northeast of the country lead nomadic lives. The mostly white Tuareg constitute the largest group of Malian nomads, who have a history of anti-state rebellions (in 1962–1964, 1990–1995 and 2007–2009) against the dominance of the black Mande tribes that inhabit the country’s southern part. The Tuareg rebellions were motivated by unfulfilled promises by the government in Bamako to provide the derelict North with necessary investment. In October 2011, various armed Tuareg groups formed the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), which aims to create an independent Tuareg state (Azawad) in northeast Mali.