An Interdisciplinary Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack!

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! I attended part of a January 20, 2006, "day workshop of interventions" — aka "a day of dialogic interventions" — at Columbia University on "Radical Politics and the Ethics of Life."[1] The event aimed "to stage a series of encounters . to bring to light . the political aporias [sic] erected by the praxis of urban guerrilla groups" in Europe and the United States from the 1960s to the 80s.[2] Hosted by Columbia's Anthropology Department, workshop speakers included veterans and leaders of the Weather Underground Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, historian Jeremy Varon, poststructuralist theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and a dozen others. The panel I sat through was just awful.[3] Veterans of Weather (as well as some fans) seem to be on a drive to rehabilitate, cleanse, and perhaps revive it — not necessarily as a new organization, but rather as an ideological component of present and future movements. There have been signs of such a sanitization and romanticization for some time. A landmark in this rehabilitation is Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir (Beacon Press 2001; Penguin Books 2003). This is a dubious account, full of anachronisms, inaccuracies, unacknowledged borrowings from unnamed sources (such as the documentary, Atomic Cafe, 17-19), adding up to an attempt to cover over the fact that Ayers was there only for a part of the things he describes in a volume that nonetheless presents itself as a memoir. It's also faux literary and soft core ("warm and wet and welcoming"(68)), "ruby mouth"(38), "she felt warm and moist"(81)), full of archaic sexism, littered with boasts of Ayers's sexual achievements, utterly untouched by feminism. -

User Office, Proposal Handling and Analysis Software

NOBUGS2002/031 October 11, 2002 Session Key: PB-1 User office, proposal handling and analysis software Jörn Beckmann, Jürgen Neuhaus Technische Universität München ZWE FRM-II D-85747 Garching, Germany [email protected] At FRM-II the installation of a user office software is under consideration, supporting tasks like proposal handling, beam time allocation, data handling and report creation. Although there are several software systems in use at major facilities, most of them are not portable to other institutes. In this paper the requirements for a modular and extendable user office software are discussed with focus on security related aspects like how to prevent a denial of service attack on fully automated systems. A suitable way seems to be the creation of a web based application using Apache as webserver, MySQL as database system and PHP as scripting language. PRESENTED AT NOBUGS 2002 Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A, November 3-5, 2002 1 Requirements of user office software At FRM-II a user office will be set up to deal with all aspects of business with guest scientists. The main part is the handling and review of proposals, allocation of beam time, data storage and retrieval, collection of experimental reports and creation of statistical reports about facility usage. These requirements make off-site access to the user office software necessary, raising some security concerns which will be addressed in chapter 2. The proposal and beam time allocation process is planned in a way that scientists draw up a short description of the experiment including a review of the scientific background and the impact results from the planned experiment might have. -

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

FP 24.2 Summer2004.Pdf (5.341Mb)

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 24, Number 2 Summer 2004 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 24, Number 2 (Summer 2004) Periodical literature is the culling edge ofwomen'sscholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing ofContents is pUblished by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from current issues ofmajor feministjournals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first pUblication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. SUbscription address. 5. Current editor. 6. -

Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Dorhn: Never the Good Girl, Not Then, not Now: An Interview By Jonah Raskin Who doesn’t have a reaction to the name and the reputation of Bernadine Dohrn? Is there anyone over the age of 60 who doesn’t remember her role at the outrageous Days of Rage demonstrations, her picture on FBI “wanted posters,” or her dramatic surrender to law enforcement officials in Chicago after a decade as a fugitive? To former members of SDS, anti-war activists, Yippies, Black Panthers, White Panthers, women’s liberationists, along with students and scholars of Weatherman and the Weather Underground, she probably needs no introduction. Sam Green featured her in his award-winning 2002 film, The Weather Underground. Todd Gitlin added to her iconic stature in his benchmark cultural history, The Sixties, though he was never on her side of the ideological splits or she on his. Dozens of books about the long decade of defiance have documented and mythologized Dohrn’s role as an American radical. Of course, her flamboyant husband and long-time partner, Bill Ayers, has been at her side for decades, aiding and abetting her much of the time, and adding to her legendary renown and notoriety. Born in 1942, and a diligent student at the University of Chicago, she attended law school there and in the late 1960s “stepped out of the role of the good girl," as she once put it. She has never really stepped back into it again, though she’s been a wife, a mother, and a professional woman for more years than she was a street fighting woman. -

HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013

THE HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013 “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “In a free society, when evil is done, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., fourth from right, walking alongside Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, second from right, in the Selma civil rights march on March 21, 1965 Table of Contents Welcome...3 Featured Speakers....10 General Information....4 Featured Artists....12 Program Schedule Community Groups....14 Friday....5 The Heschel-King Festival Saturday Morning....5 Volunteers....17 Saturday Afternoon....6 Financial Supporters....18 Saturday Evening....8 Community Sponsors....20 Mishkan Shalom is a Reconstructionist congregation in which a diverse community of progressive Jews finds a home. Mishkan’s Statement of Principles commits the community to integrate Prayer, Study and Tikkun Olam — the Jewish value for repair of the world. The synagogue, its members and Senior Rabbi Linda Holtzman are the driving force in the creation of this Festival. For more info: www.mishkan.org or call (215) 508-0226. 2 Welcome to the Heschel-King Festival Thank you for joining us for the inaugural Heschel-King Festival, a weekend of singing together, learning from each other, finding renewal and common ground, and encouraging one another’s action in the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Dr. King and Rabbi Heschel worked together in the battle for civil rights, social justice and peace. Heschel marched alongside King in Selma, Alabama, demanding voting rights for African Americans. -

A New Freedom Party -Report from Alabama MILITANT

A New Freedom Party MILITANT Published in the Interest of the Working People -Report from Alabama Vol. 30 - No. 18 Monday, May 2, 1966 Price 10c By John Benson HAYNEVILLE, Ala., April 25 — For the first time since Re construction, large numbers of Alabama Negroes will be voting this year. A struggle is already Will U.S. Prevent beginning for their votes. Some Negro leaders in the state are do ing all they can to corral the Ne gro vote for the Democratic Party. But in at least one county, Vietnam Elections? Lowndes, the Negro people have decided they are going to organize By Dick Roberts their own party, and run their APRIL 26 — Washington may own candidates. be preparing to block the proposed In February, 1965, four SNCC Vietnamese elections just as it pre workers entered Lowndes County, vented elections in that country and started working with local in 1956. This ominous possibility people who had begun registering must be considered in light of U.S. Negroes. In the course of strug Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge’s gling to register, and protesting arrogant criticisms of the planned inadequate schools, unpaved roads, and police brutality, the people of elections in an interview with SYMBOL OF FREEDOM. Black panther is symbol for Lowndes CBS correspondent Peter Kal- Lowndes County decided that they ischer, April 22. Such interviews needed their own political party. County Freedom Organization and other independent parties being are rarely given by Lodge, and They wanted to elect their own organized in counties of Alabama. must be viewed as reflecting sheriff, and to control the court Washington’s thinking. -

Dimensions of US-Cuba Relations 1965-1975 By

WHEN FEMINISM MEETS INTERNATIONALISM: Dimensions of U.S.-Cuba Relations 1965-1975 By: Pamela Neumann M.A. Candidate, Latin American Studies (University of Texas at Austin) Submitted for ILASSA Conference XXX: February 4-6, 2010 Introduction The histories of the United States and Cuba have been inextricably linked by geographical proximity, a tumultuous cercanía that over the last two centuries has had profound political, economic, and social repercussions. There is a natural scholarly tendency to examine the dynamics between these countries in terms of geopolitical strategic interests, economic trade relationships, or ideological conflict, the value of which certainly cannot be ignored. Nevertheless, the complexity of U.S.-Cuban relations cannot be fully understood apart from a wider engagement with the interactions that have taken place between the two countries outside the purview of government policy. Throughout their respective histories, interactions involving ordinary citizens from diverse backgrounds have led to enriching mutual understanding even during periods of extreme political crisis and hostility between Cuba and the United States. In addition to their impact at the individual and cultural level, these encounters have also sometimes contributed to shifts within social movements and spurred new forms of international activism. One period that exemplifies both of the aforementioned effects of citizen-level interactions came following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. In the context of the Cold War, the resulting social and economic changes in Cuba and its growing relationship with the Soviet Union heightened the United States’ concerns about the new Castro regime, leading to a rapid escalation of tensions and a suspension of formal diplomatic relations between the two Neumann 2 countries in 1960.1 However, this break in official government relations hardly signaled an end to the interactions that would occur between citizens from the two countries over the coming decades. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing

November 1965 Over 40,000 protesters led by several student activist Progression / Escalation of Anti-War groups surrounded the White House, calling for an end to the war, and Sentiment in the Sixties, 1963-1971 then marched to the Washington Monument. On that same day, President Johnson announced a significant escalation of (Page 1 of 2) U.S. involvement in Indochina, from 120,000 to 400,000 troops. May 1963 February 1966 A group of about 100 veterans attempted to return their The first coordinated Vietnam War protests occur in London and Australia. military awards/decorations to the White House in protest of the war, but These protests are organized by American pacifists during the annual were turned back. remembrance of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. In the first major student demonstration against the war hundreds of students March 1966 Anti-war demonstrations were again held around the country march through Times Square in New York City, while another 700 march in and the world, with 20,000 taking part in New York City. San Francisco. Smaller numbers also protest in Boston, Seattle, and Madison, Wisconsin. April 1966 A Gallup poll shows that 59% of Americans believe that sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake. Among the age group of 21-29, 1964 Malcolm X starts speaking out against the war in Vietnam, influencing 71% believe it was a mistake compared to only 48% of those over 50. the views of his followers. May 1966 Another large demonstration, with 10,000 picketers calling for January 1965 One of the first violent acts of protest was the Edmonton aircraft an end to the war, took place outside the White House and the Washington bombing, where 15 of 112 American military aircraft being retrofitted in Monument. -

January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South

LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 115 SANSOME STREET, 9TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94104 TELEPHONE 421.3403 ( AREA CODE 415 ) January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South Harbison National City, California 92050 Re: Casa Justicia v. Duffy, S.D. Cal. 75-0219A-GT Dear Herman: This letter just confirms our brief telephone con- versation today and agreement to dismiss the above- entitled case. I have enclosed a copy of the Stipulation for your information. Sincerely, VICTOR HARRIS VH:dc 1 VICTOR HARRIS, ESQ. NEIL GOTANDA, ESQ. 2 DIANE S. GREENBERG, ESQ. CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 3 115 Sansome Street San Francisco, California 94104 4 Telephone: (415) 421-3405 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 CASA JUSTICIA, et al., 11 ) ) Plaintiff, Civil No. 75-0219A-GT 12 ) ) 13 ) v . ) STIPULATION AND ORDER 14 ) ) JOHN DUFFY, etc., et al., 15 ) ) Defendants. ) 16 ) 17 Pursuant to Rule 41(a)(2), 18 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is hereby stipulated that the above-entitled 19 action may be dismissed, each party to bear its own costs. 20 Dated: December 28, 1977. 21 y VICTOR HARRIS, one 22 of the attorneys for Plaintiff CASA JUSTICIA 23 24 Donald L. Clark, County C,212E5e1 25 Dated: 26 LLOYD. M. HARMON, JR., Deputy, 27 Attorneys for Defendants 28 ORDER Based upon the Stipulation of the parties 29 hereto, and good cause appearing therefor: 30 IT IS SO ORDERED. 31 Dated: 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 328 CAYUGA STREET P.O. -

Hanukkah Is Not Hypocrisy Rabbi Michael Lerner's Rejoinder To

Hanukkah is not Hypocrisy Rabbi Michael Lerner’s rejoinder to Michael David Lukas December 2, 2018 [The real miracle of Hanukkah is]: that people can unify against oppression and overcome what at first seems like overwhelming odds against the forces that have all the conventional instruments of power in their hands, if and only if they can believe that there is something about the universe that makes such a struggle winnable. On the eve of Chanukah, Dec. 2nd, the N.Y. Times chose to publish an article entitled “The Hypocrisy of Hanukah” by Michael David Lukas. It is worth exploring not only because of the way it reveal the shallowness of contemporary forms of Judaism that are more about identity than about belief and boiled down to please a mild form of liberalism, but also because of the way it reveals how ill suited contemporary liberalism is to understand the appeal of right-wing nationalist chauvinism and hence to effectively challenge it. Lukas portrays the problem of contemporary non-religious Jews in face of the powerful and pervasive symbols of music of Christmas. Like most Jews, he doesn’t believe in the supposed miracle of a light that burned for eight days, so he digs deeper and what he finds outrages him: that Chanukah was, in his representation, a battle between cosmopolitan Jews who wanted to embrace the enlightened thought of Greek culture and a militaristic chauvinistic fundamentalist force, the Maccabees. Since he is sure that those Maccabees would reject him and his liberal ideas and politics, he is tempted to abandon the whole thing, but he decides not to do so because he needs something at this time of year to offer his young daughter who is attracted to Santa Claus, because he thinks that offering his daughter something he personally believes to be worse than nonsense is, as he puts, “it’s all about beating Santa.” I want to sympathize with his plight but offer some very different perspectives. -

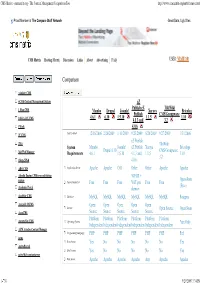

CMS Matrix - Cmsmatrix.Org - the Content Management Comparison Tool

CMS Matrix - cmsmatrix.org - The Content Management Comparison Tool http://www.cmsmatrix.org/matrix/cms-matrix Proud Member of The Compare Stuff Network Great Data, Ugly Sites CMS Matrix Hosting Matrix Discussion Links About Advertising FAQ USER: VISITOR Compare Search Return to Matrix Comparison <sitekit> CMS +CMS Content Management System eZ Publish eZ TikiWiki 1 Man CMS Mambo Drupal Joomla! Xaraya Bricolage Publish CMS/Groupware 4.6.1 6.10 1.5.10 1.1.5 1.10 1024 AJAX CMS 4.1.3 and 3.2 1Work 4.0.6 2F CMS Last Updated 12/16/2006 2/26/2009 1/11/2009 9/23/2009 8/20/2009 9/27/2009 1/31/2006 eZ Publish 2flex TikiWiki System Mambo Joomla! eZ Publish Xaraya Bricolage Drupal 6.10 CMS/Groupware 360 Web Manager Requirements 4.6.1 1.5.10 4.1.3 and 1.1.5 1.10 3.2 4Steps2Web 4.0.6 ABO.CMS Application Server Apache Apache CGI Other Other Apache Apache Absolut Engine CMS/news publishing 30EUR + system Open-Source Approximate Cost Free Free Free VAT per Free Free (Free) Academic Portal domain AccelSite CMS Database MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL Postgres Accessify WCMS Open Open Open Open Open License Open Source Open Source AccuCMS Source Source Source Source Source Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Accura Site CMS Operating System *nix Only Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent ACM Ariadne Content Manager Programming Language PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP Perl acms Root Access Yes No No No No No Yes ActivePortail Shell Access Yes No No No No No Yes activeWeb contentserver Web Server Apache Apache