Using Wordpress to Manage Geocontent and Promote Regional Food Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

User Office, Proposal Handling and Analysis Software

NOBUGS2002/031 October 11, 2002 Session Key: PB-1 User office, proposal handling and analysis software Jörn Beckmann, Jürgen Neuhaus Technische Universität München ZWE FRM-II D-85747 Garching, Germany [email protected] At FRM-II the installation of a user office software is under consideration, supporting tasks like proposal handling, beam time allocation, data handling and report creation. Although there are several software systems in use at major facilities, most of them are not portable to other institutes. In this paper the requirements for a modular and extendable user office software are discussed with focus on security related aspects like how to prevent a denial of service attack on fully automated systems. A suitable way seems to be the creation of a web based application using Apache as webserver, MySQL as database system and PHP as scripting language. PRESENTED AT NOBUGS 2002 Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A, November 3-5, 2002 1 Requirements of user office software At FRM-II a user office will be set up to deal with all aspects of business with guest scientists. The main part is the handling and review of proposals, allocation of beam time, data storage and retrieval, collection of experimental reports and creation of statistical reports about facility usage. These requirements make off-site access to the user office software necessary, raising some security concerns which will be addressed in chapter 2. The proposal and beam time allocation process is planned in a way that scientists draw up a short description of the experiment including a review of the scientific background and the impact results from the planned experiment might have. -

Privacy Protection for Smartphones: an Ontology-Based Firewall Johanne Vincent, Christine Porquet, Maroua Borsali, Harold Leboulanger

Privacy Protection for Smartphones: An Ontology-Based Firewall Johanne Vincent, Christine Porquet, Maroua Borsali, Harold Leboulanger To cite this version: Johanne Vincent, Christine Porquet, Maroua Borsali, Harold Leboulanger. Privacy Protection for Smartphones: An Ontology-Based Firewall. 5th Workshop on Information Security Theory and Prac- tices (WISTP), Jun 2011, Heraklion, Crete, Greece. pp.371-380, 10.1007/978-3-642-21040-2_27. hal-00801738 HAL Id: hal-00801738 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00801738 Submitted on 18 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Privacy Protection for Smartphones: An Ontology-Based Firewall Johann Vincent, Christine Porquet, Maroua Borsali, and Harold Leboulanger GREYC Laboratory, ENSICAEN - CNRS University of Caen-Basse-Normandie, 14000 Caen, France {johann.vincent,christine.porquet}@greyc.ensicaen.fr, {maroua.borsali,harold.leboulanger}@ecole.ensicaen.fr Abstract. With the outbreak of applications for smartphones, attempts to collect personal data without their user’s consent are multiplying and the protection of users privacy has become a major issue. In this paper, an approach based on semantic web languages (OWL and SWRL) and tools (DL reasoners and ontology APIs) is described. -

Geo-Text Data and Data-Driven Geospatial Semantics

Geo-Text Data and Data-Driven Geospatial Semantics Yingjie Hu GSDA Lab, Department of Geography, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, 37996, USA Abstract Many datasets nowadays contain links between geographic locations and natural language texts. These links can be geotags, such as geotagged tweets or geotagged Wikipedia pages, in which location coordinates are explicitly attached to texts. These links can also be place mentions, such as those in news articles, travel blogs, or historical archives, in which texts are implicitly connected to the mentioned places. This kind of data is referred to as geo- text data. The availability of large amounts of geo-text data brings both challenges and opportunities. On the one hand, it is challenging to automatically process this kind of data due to the unstructured texts and the complex spatial footprints of some places. On the other hand, geo-text data offers unique research opportunities through the rich information contained in texts and the special links between texts and geography. As a result, geo-text data facilitates various studies especially those in data-driven geospatial semantics. This paper discusses geo-text data and related concepts. With a focus on data-driven research, this paper systematically reviews a large number of studies that have discovered multiple types of knowledge from geo-text data. Based on the literature review, a generalized workflow is extracted and key challenges for future work are discussed. Keywords: geo-text data, spatial analysis, natural language processing, spatial and textual data analysis, data-driven geospatial semantics, spatial data science. 1. Introduction Recent years have witnessed an unprecedented increase in the volume, variety, and veloc- ity of data from different sources (Miller and Goodchild, 2015). -

Wiki Semantics Via Wiki Templating

Chapter XXXIV Wiki Semantics via Wiki Templating Angelo Di Iorio Department of Computer Science, University of Bologna, Italy Fabio Vitali Department of Computer Science, University of Bologna, Italy Stefano Zacchiroli Universitè Paris Diderot, PPS, UMR 7126, Paris, France ABSTRACT A foreseeable incarnation of Web 3.0 could inherit machine understandability from the Semantic Web, and collaborative editing from Web 2.0 applications. We review the research and development trends which are getting today Web nearer to such an incarnation. We present semantic wikis, microformats, and the so-called “lowercase semantic web”: they are the main approaches at closing the technological gap between content authors and Semantic Web technologies. We discuss a too often neglected aspect of the associated technologies, namely how much they adhere to the wiki philosophy of open editing: is there an intrinsic incompatibility between semantic rich content and unconstrained editing? We argue that the answer to this question can be “no”, provided that a few yet relevant shortcomings of current Web technologies will be fixed soon. INTRODUCTION Web 3.0 can turn out to be many things, it is hard to state what will be the most relevant while still debating on what Web 2.0 [O’Reilly (2007)] has been. We postulate that a large slice of Web 3.0 will be about the synergies between Web 2.0 and the Semantic Web [Berners-Lee et al. (2001)], synergies that only very recently have begun to be discovered and exploited. We base our foresight on the observation that Web 2.0 and the Semantic Web are converging to a common point in their initially split evolution lines. -

Hidden Meaning

FEATURES Microdata and Microformats Kit Sen Chin, 123RF.com Chin, Sen Kit Working with microformats and microdata Hidden Meaning Programs aren’t as smart as humans when it comes to interpreting the meaning of web information. If you want to maximize your search rank, you might want to dress up your HTML documents with microformats and microdata. By Andreas Möller TML lets you mark up sections formats and microdata into your own source code for the website shown in of text as headings, body text, programs. Figure 1 – an HTML5 document with a hyperlinks, and other web page business card. The Heading text block is H elements. However, these defi- Microformats marked up with the element h1. The text nitions have nothing to do with the HTML was originally designed for hu- for the business card is surrounded by meaning of the data: Does the text refer mans to read, but with the explosive the div container element, and <br/> in- to a person, an organization, a product, growth of the web, programs such as troduces a line break. or an event? Microformats [1] and their search engines also process HTML data. It is easy for a human reader to see successor, microdata [2] make the mean- What do programs that read HTML data that the data shown in Figure 1 repre- ing a bit more clear by pointing to busi- typically find? Listing 1 shows the HTML sents a business card – even if the text is ness cards, product descriptions, offers, and event data in a machine-readable LISTING 1: HTML5 Document with Business Card way. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal

FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISMFast Capitalism FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM ISSNFAST XXX-XXXX CAPITALISM FAST Volume 1 • Issue 1 • 2005 CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM -

Web GIS in Practice VI: a Demo Playlist of Geo-Mashups for Public Health Neogeographers Maged N Kamel Boulos*1, Matthew Scotch2, Kei-Hoi Cheung2,3 and David Burden4

International Journal of Health Geographics BioMed Central Editorial Open Access Web GIS in practice VI: a demo playlist of geo-mashups for public health neogeographers Maged N Kamel Boulos*1, Matthew Scotch2, Kei-Hoi Cheung2,3 and David Burden4 Address: 1Faculty of Health and Social Work, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, Devon, PL4 8AA, UK, 2Center for Medical Informatics, School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 3Departments of Anesthesiology and Genetics, School of Medicine, and Department of Computer Science, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA and 4Daden Limited, 103 Oxford Rd, Moseley, Birmingham, B13 9SG, UK Email: Maged N Kamel Boulos* - [email protected]; Matthew Scotch - [email protected]; Kei- Hoi Cheung - [email protected]; David Burden - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 18 July 2008 Received: 6 July 2008 Accepted: 18 July 2008 International Journal of Health Geographics 2008, 7:38 doi:10.1186/1476-072X-7-38 This article is available from: http://www.ij-healthgeographics.com/content/7/1/38 © 2008 Boulos et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract 'Mashup' was originally used to describe the mixing together of musical tracks to create a new piece of music. The term now refers to Web sites or services that weave data from different sources into a new data source or service. -

Microformats the Next (Small) Thing on the Semantic Web?

Standards Editor: Jim Whitehead • [email protected] Microformats The Next (Small) Thing on the Semantic Web? Rohit Khare • CommerceNet “Designed for humans first and machines second, microformats are a set of simple, open data formats built upon existing and widely adopted standards.” — Microformats.org hen we speak of the “evolution of the is precisely encoding the great variety of person- Web,” it might actually be more appropri- al, professional, and genealogical relationships W ate to speak of “intelligent design” — we between people and organizations. By contrast, can actually point to a living, breathing, and an accidental challenge is that any blogger with actively involved Creator of the Web. We can even some knowledge of HTML can add microformat consult Tim Berners-Lee’s stated goals for the markup to a text-input form, but uploading an “promised land,” dubbed the Semantic Web. Few external file dedicated to machine-readable use presume we could reach those objectives by ran- remains forbiddingly complex with most blog- domly hacking existing Web standards and hop- ging tools. ing that “natural selection” by authors, software So, although any intelligent designer ought to developers, and readers would ensure powerful be able to rely on the long-established facility of enough abstractions for it. file transfer to publish the “right” model of a social Indeed, the elegant and painstakingly inter- network, the path of least resistance might favor locked edifice of technologies, including RDF, adding one of a handful of fixed tags to an exist- XML, and query languages is now growing pow- ing indirect form — the “blogroll” of hyperlinks to erful enough to attack massive information chal- other people’s sites. -

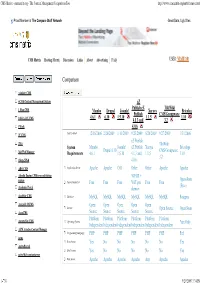

CMS Matrix - Cmsmatrix.Org - the Content Management Comparison Tool

CMS Matrix - cmsmatrix.org - The Content Management Comparison Tool http://www.cmsmatrix.org/matrix/cms-matrix Proud Member of The Compare Stuff Network Great Data, Ugly Sites CMS Matrix Hosting Matrix Discussion Links About Advertising FAQ USER: VISITOR Compare Search Return to Matrix Comparison <sitekit> CMS +CMS Content Management System eZ Publish eZ TikiWiki 1 Man CMS Mambo Drupal Joomla! Xaraya Bricolage Publish CMS/Groupware 4.6.1 6.10 1.5.10 1.1.5 1.10 1024 AJAX CMS 4.1.3 and 3.2 1Work 4.0.6 2F CMS Last Updated 12/16/2006 2/26/2009 1/11/2009 9/23/2009 8/20/2009 9/27/2009 1/31/2006 eZ Publish 2flex TikiWiki System Mambo Joomla! eZ Publish Xaraya Bricolage Drupal 6.10 CMS/Groupware 360 Web Manager Requirements 4.6.1 1.5.10 4.1.3 and 1.1.5 1.10 3.2 4Steps2Web 4.0.6 ABO.CMS Application Server Apache Apache CGI Other Other Apache Apache Absolut Engine CMS/news publishing 30EUR + system Open-Source Approximate Cost Free Free Free VAT per Free Free (Free) Academic Portal domain AccelSite CMS Database MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL Postgres Accessify WCMS Open Open Open Open Open License Open Source Open Source AccuCMS Source Source Source Source Source Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Accura Site CMS Operating System *nix Only Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent ACM Ariadne Content Manager Programming Language PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP Perl acms Root Access Yes No No No No No Yes ActivePortail Shell Access Yes No No No No No Yes activeWeb contentserver Web Server Apache Apache -

Data Models for Home Services

__________________________________________PROCEEDING OF THE 13TH CONFERENCE OF FRUCT ASSOCIATION Data Models for Home Services Vadym Kramar, Markku Korhonen, Yury Sergeev Oulu University of Applied Sciences, School of Engineering Raahe, Finland {vadym.kramar, markku.korhonen, yury.sergeev}@oamk.fi Abstract An ultimate penetration of communication technologies allowing web access has enriched a conception of smart homes with new paradigms of home services. Modern home services range far beyond such notions as Home Automation or Use of Internet. The services expose their ubiquitous nature by being integrated into smart environments, and provisioned through a variety of end-user devices. Computational intelligence require a use of knowledge technologies, and within a given domain, such requirement as a compliance with modern web architecture is essential. This is where Semantic Web technologies excel. A given work presents an overview of important terms, vocabularies, and data models that may be utilised in data and knowledge engineering with respect to home services. Index Terms: Context, Data engineering, Data models, Knowledge engineering, Semantic Web, Smart homes, Ubiquitous computing. I. INTRODUCTION In recent years, a use of Semantic Web technologies to build a giant information space has shown certain benefits. Rapid development of Web 3.0 and a use of its principle in web applications is the best evidence of such benefits. A traditional database design in still and will be widely used in web applications. One of the most important reason for that is a vast number of databases developed over years and used in a variety of applications varying from simple web services to enterprise portals. In accordance to Forrester Research though a growing number of document, or knowledge bases, such as NoSQL is not a hype anymore [1]. -

Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science Or Volunteered Geographic Information? the Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information Linda See 1,*, Peter Mooney 2, Giles Foody 3, Lucy Bastin 4, Alexis Comber 5, Jacinto Estima 6, Steffen Fritz 1, Norman Kerle 7, Bin Jiang 8, Mari Laakso 9, Hai-Ying Liu 10, Grega Milˇcinski 11, Matej Nikšiˇc 12, Marco Painho 6, Andrea P˝odör 13, Ana-Maria Olteanu-Raimond 14 and Martin Rutzinger 15 1 International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Schlossplatz 1, Laxenburg A2361, Austria; [email protected] 2 Department of Computer Science, Maynooth University, Maynooth W23 F2H6, Ireland; [email protected] 3 School of Geography, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK; [email protected] 4 School of Engineering and Applied Science, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK; [email protected] 5 School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; [email protected] 6 NOVA IMS, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (UNL), 1070-312 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] (J.E.); [email protected] (M.P.) 7 Department of Earth Systems Analysis, ITC/University of Twente, Enschede 7500 AE, The Netherlands; [email protected] 8 Faculty of Engineering and Sustainable Development, Division of GIScience, University of Gävle, Gävle 80176, Sweden; [email protected] 9 Finnish Geospatial Research Institute, Kirkkonummi 02430, Finland; mari.laakso@nls.fi 10 Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU), Kjeller 2027, Norway; [email protected] -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Dimethyl Fumarate Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis, through the Activation of Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Pathways. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n185057 Journal Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(4) ISSN 2076-3921 Authors Li, Shiri Takasu, Chie Lau, Hien et al. Publication Date 2020-04-24 DOI 10.3390/antiox9040354 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California antioxidants Article Dimethyl Fumarate Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis, through the Activation of Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant and Anti-nflammatory Pathways Shiri Li 1, Chie Takasu 1 , Hien Lau 1, Lourdes Robles 1, Kelly Vo 1, Ted Farzaneh 2, Nosratola D. Vaziri 3, Michael J. Stamos 1 and Hirohito Ichii 1,* 1 Department of Surgery, University of California, Irvine, CA 92868, USA; [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (C.T.); [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (K.V.); [email protected] (M.J.S.) 2 Department of Pathology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92868, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA 92868, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-714-456-8590; Fax: +1-714-456-8796 Received: 14 March 2020; Accepted: 22 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Oxidative stress and chronic inflammation play critical roles in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (UC) and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). A previous study has demonstrated that dimethyl fumarate (DMF) protects mice from dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis via its potential antioxidant capacity, and by inhibiting the activation of the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.