Dimensions of US-Cuba Relations 1965-1975 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

A New Freedom Party -Report from Alabama MILITANT

A New Freedom Party MILITANT Published in the Interest of the Working People -Report from Alabama Vol. 30 - No. 18 Monday, May 2, 1966 Price 10c By John Benson HAYNEVILLE, Ala., April 25 — For the first time since Re construction, large numbers of Alabama Negroes will be voting this year. A struggle is already Will U.S. Prevent beginning for their votes. Some Negro leaders in the state are do ing all they can to corral the Ne gro vote for the Democratic Party. But in at least one county, Vietnam Elections? Lowndes, the Negro people have decided they are going to organize By Dick Roberts their own party, and run their APRIL 26 — Washington may own candidates. be preparing to block the proposed In February, 1965, four SNCC Vietnamese elections just as it pre workers entered Lowndes County, vented elections in that country and started working with local in 1956. This ominous possibility people who had begun registering must be considered in light of U.S. Negroes. In the course of strug Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge’s gling to register, and protesting arrogant criticisms of the planned inadequate schools, unpaved roads, and police brutality, the people of elections in an interview with SYMBOL OF FREEDOM. Black panther is symbol for Lowndes CBS correspondent Peter Kal- Lowndes County decided that they ischer, April 22. Such interviews needed their own political party. County Freedom Organization and other independent parties being are rarely given by Lodge, and They wanted to elect their own organized in counties of Alabama. must be viewed as reflecting sheriff, and to control the court Washington’s thinking. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal

FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISMFast Capitalism FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM ISSNFAST XXX-XXXX CAPITALISM FAST Volume 1 • Issue 1 • 2005 CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM -

January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South

LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 115 SANSOME STREET, 9TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94104 TELEPHONE 421.3403 ( AREA CODE 415 ) January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South Harbison National City, California 92050 Re: Casa Justicia v. Duffy, S.D. Cal. 75-0219A-GT Dear Herman: This letter just confirms our brief telephone con- versation today and agreement to dismiss the above- entitled case. I have enclosed a copy of the Stipulation for your information. Sincerely, VICTOR HARRIS VH:dc 1 VICTOR HARRIS, ESQ. NEIL GOTANDA, ESQ. 2 DIANE S. GREENBERG, ESQ. CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 3 115 Sansome Street San Francisco, California 94104 4 Telephone: (415) 421-3405 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 CASA JUSTICIA, et al., 11 ) ) Plaintiff, Civil No. 75-0219A-GT 12 ) ) 13 ) v . ) STIPULATION AND ORDER 14 ) ) JOHN DUFFY, etc., et al., 15 ) ) Defendants. ) 16 ) 17 Pursuant to Rule 41(a)(2), 18 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is hereby stipulated that the above-entitled 19 action may be dismissed, each party to bear its own costs. 20 Dated: December 28, 1977. 21 y VICTOR HARRIS, one 22 of the attorneys for Plaintiff CASA JUSTICIA 23 24 Donald L. Clark, County C,212E5e1 25 Dated: 26 LLOYD. M. HARMON, JR., Deputy, 27 Attorneys for Defendants 28 ORDER Based upon the Stipulation of the parties 29 hereto, and good cause appearing therefor: 30 IT IS SO ORDERED. 31 Dated: 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 328 CAYUGA STREET P.O. -

War Rites and Women's Rights

Smith ScholarWorks Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications Study of Women and Gender Spring 2005 Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth Armstrong Smith College, [email protected] Vijay Prashad Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Elisabeth and Prashad, Vijay, "Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights" (2005). Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs/22 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Author(s): Elisabeth B. Armstrong and Vijay Prashad Source: CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, terror wars (spring 2005), pp. 213- 253 Published by: Michigan State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41949472 Accessed: 14-01-2020 19:07 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Michigan State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to CR: The New Centennial Review This content downloaded from 131.229.19.247 on Tue, 14 Jan 2020 19:07:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Solidarity War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth b. -

Coalition Dissolution, Mobilization, and Network Dynamics in the U.S

COALITION DISSOLUTION, MOBILIZATION, AND NETWORK DYNAMICS IN THE U.S. ANTIWAR MOVEMENT Michael T. Heaney and Fabio Rojas ABSTRACT Coalition formation and dissolution are integral parts of social movement politics. This article addresses two questions about the effect of coalition politics on organizational processes within social movements. First, how does coalition leadership influence who attends mass demonstrations? Second, how does the dissolution of a coalition affect the locations of organizations in activist networks? The case of schism between United for Peace and Justice (UFPJ) and Act Now to Stop War and End Racism (ANSWER) in the contemporary American antiwar movement (2001–2007) is examined. Survey results demonstrate that variations in coalition leadership do not significantly affect protest demographics, though they do attract supporters with different political attitudes, levels of commitment, and organizational affiliations. Further, network analysis establishes that coalition dissolution weakens the ties between previous coalition partners and creates opportunities for actors uninvolved in the split to reaffirm and improve brokerage opportunities. The end result is that preexisting network structures serve to mitigate the effects of coalition dissolution on social movements. Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, Volume 28, 39–82 Copyright r 2008 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 0163-786X/doi:10.1016/S0163-786X(08)28002-X 39 40 MICHAEL T. HEANEY AND FABIO ROJAS When public approval of President George W. Bush’s handling of the Iraq War stood at an unprecedented low in September 2005, the American antiwar movement seized the opportunity to get out its message.1 The nation’s two leading grassroots antiwar coalitions – United for Peace and Justice (UFPJ) and Act Now to Stop War and End Racism (ANSWER) – formed a grand coalition to sponsor a march in Washington, DC, on September 24, 2005. -

The Politics of US Feminist Internationalism and Cuba: Solidarities and Fractures on the Venceremos Brigades, 1969-89

Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 2(1), 03 ISSN: 2542-4920 The Politics of US Feminist Internationalism and Cuba: Solidarities and Fractures on the Venceremos Brigades, 1969-89 Karen W. Tice 1* Published: March 19, 2018 ABSTRACT Despite US travel bans to Cuba, a wide spectrum of US feminist and radical activists defied and crossed geo-political borders to participate in unique modes of solidarity activism and alliances with Cuba revolutionaries. Based on the narratives of US feminist political travellers who joined the Venceremos Brigades, an anti-imperialist radical education project, this article analyses the difficult conversations about feminism, gender politics, homophobia, racism, cultural imperialism, revolutionary priorities, social change strategies, and intersectionality as well as the productive organisational linkages that were generated by this political travel. This article highlights how political differences were both managed and/or silenced within transnational activist encounters, and concludes by suggesting the import of these debates for building and sustaining multi-issue and coalitional affinities within contemporary transnational feminist organising and solidarity delegations. Keywords: Venceremos Brigades, transnational feminism, solidarity delegations, cultural imperialism, geo- political border crossings INTRODUCTION Beginning in the 1960s, and partly as a response to the liberation struggles occurring across the globe, many US activists claimed political kinship and -

Press Kit /// Pg2 DIRECTORS STATEMENT

SYNOPSIS DISRUPTION tells the story of the greatest crisis mankind has ever faced and the movement rising to fight it by weaving together commentary from the most recognized voices analyzing climate, politics and society today with behind-the-scenes footage of the efforts to organize The People’s Climate March - the largest climate rally in history. Featuring James Hansen, Naomi Oreskes, Van Jones, Bill McKibben, Chris Hayes, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, Naomi Klein, Rajendra Pachauri, Justin Gillis, among others - DISRUPTION makes plain the urgency of the present by laying bare the science behind the terrifying tipping points we are threatening to trigger, the failure of our politi- cal process to prevent these catastrophes and the need for a popular movement to challenge these realities. Drawing on insights into the power of popular movements to change the character of society from veteran organiz- ers responsible for the most significant political demonstrations of the last half century, DISRUPTION documents the first steps of the fateful battle to bend the course of history. Disruption - WatchDisruption.com /// Press Kit /// pg2 DIRECTORS STATEMENT We could not imagine a more important story than the climate crisis and the movement fighting to meet it. Disruption - WatchDisruption.com /// Press Kit /// pg3 CAST AND CREW A PF PICTURES PRODUCTION “DISRUPTION” A FILM BY KELLY NYKS AND JARED P. SCOTT PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY Kelly Nyks & Jared P. Scott FEATURING Van Jones James Hansen Naomi Oreskes Heidi Cullen Ricken Patel Bill McKibben -

U Nuni C a Ti

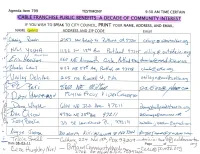

Agenda ltem 799 TEST|MONY 9:30 AM T|ME CERTATN CABLE FRANCHISE PUBLIC BENEFITS: A DECADE OF COIvIIUUT¡ry IuruRTsT lF YOU WISH TO SPEAK TO CITY COUNCIL, PRINT yOUR NAME, ADDRESS, AND EMA¡L. NAME ADDRESS AND ZIP CODE Email C¿ol. ?rr.x ¿-1ç-l ¡^, (^faù (.r Cyã.t c ø c.,\bq\wtka.u'q, \J b\\L\ \ o (ftA l\z t 5\^r \3+d å^ P*[ {^^! 11zo -t û nu4r)h in e?a ^i\ì f - Õ /r,-- l/),;^'r:i: tt6t( ÅE Å;^rr".J( Cr.lo P,,ff^l rro dnorrl ron@-t"eú, kl 2. or.u, L¿-;ç r+.r& C[r*í.t 1rZ+ l,/E çTl ) ?"*+{a/, ofL 17219 CA,/^eed<*.ok5 U^i l"{ Ü¿jr^ tl'¿ ?aÇ y\ø ?-*dt d, p& f,r-.7*r, {eø t{tr ø;/1,/ r-?<-ã*us,Q- lrb cd' I 'Í) tH h+"rs-nt ¡ ftl(ú- ft.vç l/ t D€zGrr*rtr, (rloq t t ( /Þ,1 D *^ Ull.,.lu-- rJÉ 3z"N Nno- 9 7¿ åo^^^L.rl l*¡0,*!+\,o* L, a rot f +f :òwö*oN, -r- ¿./ { 4-t1t xt€, Z*q/ror* 172 // 2Sl on <.q q,@â,-r^' c^rgz .^û FJ yt ltLlßøe\,n h , 3b aü t err s(h^.rst R , \?Z t '| 4r,rd*t^- c+ c.^>t t*l ,. /oo ,¡orrq {,7t r'ì4f ,.- t,trftf ç Pil lTzt¿ þZSxrfa.-*<PS, â.cp' tô :- fffdaG¡'daSnoQ! S^.e-Q-t ---;J8'¿.a, zz+z7 rvwfvu/ l LBn,Et( Pox'rl\-= rC\q, çn.{l€ p¡\ c*[J"no...{=,GT " ,/ i "!ao1 -.{i.ù,page of "*tJ or7 -Date0S-03-ll ?a@gfayy"2ftyy,V*tux u Q;îE^rlrtey N u, ¡ - or;yrÏ.oi,ao n') miÌ ltrl ."-f.l * i' \ *.:1 * " , \'¡e 'Zl.tl " ryi'+wÅlt Ð J,L çfJ 1'¿. -

Sandy Lillydahl Venceremos Brigade Photograph Collection

Special Collections and University Archives : University Libraries Sandy Lillydahl Venceremos Brigade Photograph Collection 1970-2005 (Bulk: 1970) 1 box (0.25 linear foot) Call no.: FS 056 Collection overview A 1969 graduate of Smith College and member of Students for a Democratic Society, Sandy Lillydahl took part in the second contingent of the Venceremos Brigade. Between February and April 1970, Lillydahl and traveled to Cuba as an expression of solidarity with the Cuban people and to assist in the sugarcane harvest. The 35 color snapshots that comprise the Lillydahl collection document the work of during the New England contingent of the second Venceremos Brigade as they worked the sugarcane fields in Aguacate, Cuba, and toured the country. Each image is accompanied by a caption supplied by Lillydahl in 2005, describing the scene and reflecting on her experiences, and the collection also includes copies of the file kept by the FBI on Lillydahl, obtained by her through the Freedom of Information Act in 1975. See similar SCUA collections: Agriculture Central and South America Communism and Socialism Photographs Political activism Women Background on Sandy Lillydahl In 1969, the antiwar activist and former president of Students for a Democratic Society, Carl Oglesby, proposed that the SDS should organize a contingent of American students to travel to Cuba as a gesture of revolutionary solidarity. As guests of the Cuban government, members of what would be called the Venceremos Brigade would go not as tourists, but as workers intending to assist the struggling nation reach its ambitious goal of harvesting 10 million tons of sugarcane for export, allowing them to raise capital to shore up the economy and lessen dependence on the Soviet Union. -

Nuclear Disarmament Campaigns 1957-1985

LESSON PLANS ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY A DANGER UNLIKE ANY DANGER: Nuclear Disarmament Campaigns 1957-1985 OVERVIEW COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS Students will examine primary sources to consider responses to nuclear power and weapons in New York City during the Cold War. Grade 4: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.4.1 Refer to details and examples in a text when STUDENT GOALS explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. Students will study everyday objects and consider their historical purpose. Grades 6-8: Students will analyze a protest item to understand different concerns CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support about nuclear power. analysis of primary and secondary sources. Students will synthesize their observations and analysis with a hands-on activity. Grades 9-10: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.1 Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. The Museum of the City of New York 1220 5th Avenue at 104th Street www.mcny.org 1 LESSON PLANS ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY A DANGER UNLIKE ANY DANGER: Nuclear Disarmament Campaigns 1957-1985 KEY TERMS/VOCABULARY Nuclear Fallout Proliferation Disarmament The Cold War ACTIVISTS Dorothy Day Cora Weiss A.J. Muste Leslie Cagan Jack O’Dell ORGANIZATIONS Mobilization for Survival SANE War Resisters League Women Strike for Peace The Museum of the City of New York 1220 5th Avenue at 104th Street www.mcny.org 2 LESSON PLANS ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY A DANGER UNLIKE ANY DANGER: Nuclear Disarmament Campaigns 1957-1985 INTRODUCING RESOURCES 1, 2 & 3 On June 12, 1982, the largest protest in American history converged in New York, as demonstrators marched to the United Nations to demand an end to nuclear weapons. -

Fidel Castro International Socialist Review, Pages 9-18

'Minibrigade' movement in Cuba TH£ A speech by Fidel Castro International Socialist Review, pages 9-18 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 52/NO. 4 JANUARY 29, 1988 $1.00 Coast-to-coast de01onstrations will protest U.S. aid to contras Nicaraguans 75 cities press fight plan events for peace on Jan. 25 Opponents of the U.S .-sponsored and fi BY LARRY SEIGLE nanced war against the people of Nicaragua MANAGUA, Nicaragua, Jan. 20 - and Central America need to organize mas The Sandinista government has lifted the sive, visible, and broadly sponsored pro country's state of emergency. This step tests now against the Reagan administra creates better conditions. for the workers tion's proposal for tens of millions of dol and peasants to organize and fight to carry lars more in aid to the contras. the revolution forward . Protest actions are already scheduled to All constitutional guarantees - includ take place in Washington, D.C., San Fran ing the right to demonstrate and the right to cisco, and 75 other cities on January 25 strike - are now in effect. when Reagan delivers his State of the At the same time, the government has Union address to Congress. Central Amer- announced a series of concessions to Washington in an attempt to help bring an end to the contra war. EDITORIAL These measures include agreement to negotiate directly with the contras about ican solidarity groups in Washington are terms for a cease-fire. Previously the San also organizing a march and rally at the dinistas had agreed only to indirect discus Capitol on February 2, the day before Con sions through an intermediary .