RELIGION in the DEBATE BEFORE the IRAQ WAR a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

A New Freedom Party -Report from Alabama MILITANT

A New Freedom Party MILITANT Published in the Interest of the Working People -Report from Alabama Vol. 30 - No. 18 Monday, May 2, 1966 Price 10c By John Benson HAYNEVILLE, Ala., April 25 — For the first time since Re construction, large numbers of Alabama Negroes will be voting this year. A struggle is already Will U.S. Prevent beginning for their votes. Some Negro leaders in the state are do ing all they can to corral the Ne gro vote for the Democratic Party. But in at least one county, Vietnam Elections? Lowndes, the Negro people have decided they are going to organize By Dick Roberts their own party, and run their APRIL 26 — Washington may own candidates. be preparing to block the proposed In February, 1965, four SNCC Vietnamese elections just as it pre workers entered Lowndes County, vented elections in that country and started working with local in 1956. This ominous possibility people who had begun registering must be considered in light of U.S. Negroes. In the course of strug Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge’s gling to register, and protesting arrogant criticisms of the planned inadequate schools, unpaved roads, and police brutality, the people of elections in an interview with SYMBOL OF FREEDOM. Black panther is symbol for Lowndes CBS correspondent Peter Kal- Lowndes County decided that they ischer, April 22. Such interviews needed their own political party. County Freedom Organization and other independent parties being are rarely given by Lodge, and They wanted to elect their own organized in counties of Alabama. must be viewed as reflecting sheriff, and to control the court Washington’s thinking. -

Dimensions of US-Cuba Relations 1965-1975 By

WHEN FEMINISM MEETS INTERNATIONALISM: Dimensions of U.S.-Cuba Relations 1965-1975 By: Pamela Neumann M.A. Candidate, Latin American Studies (University of Texas at Austin) Submitted for ILASSA Conference XXX: February 4-6, 2010 Introduction The histories of the United States and Cuba have been inextricably linked by geographical proximity, a tumultuous cercanía that over the last two centuries has had profound political, economic, and social repercussions. There is a natural scholarly tendency to examine the dynamics between these countries in terms of geopolitical strategic interests, economic trade relationships, or ideological conflict, the value of which certainly cannot be ignored. Nevertheless, the complexity of U.S.-Cuban relations cannot be fully understood apart from a wider engagement with the interactions that have taken place between the two countries outside the purview of government policy. Throughout their respective histories, interactions involving ordinary citizens from diverse backgrounds have led to enriching mutual understanding even during periods of extreme political crisis and hostility between Cuba and the United States. In addition to their impact at the individual and cultural level, these encounters have also sometimes contributed to shifts within social movements and spurred new forms of international activism. One period that exemplifies both of the aforementioned effects of citizen-level interactions came following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. In the context of the Cold War, the resulting social and economic changes in Cuba and its growing relationship with the Soviet Union heightened the United States’ concerns about the new Castro regime, leading to a rapid escalation of tensions and a suspension of formal diplomatic relations between the two Neumann 2 countries in 1960.1 However, this break in official government relations hardly signaled an end to the interactions that would occur between citizens from the two countries over the coming decades. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal

FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISMFast Capitalism FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM ISSNFAST XXX-XXXX CAPITALISM FAST Volume 1 • Issue 1 • 2005 CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South

LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 115 SANSOME STREET, 9TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94104 TELEPHONE 421.3403 ( AREA CODE 415 ) January 27, 1978 Mr. Herman Baca 105 South Harbison National City, California 92050 Re: Casa Justicia v. Duffy, S.D. Cal. 75-0219A-GT Dear Herman: This letter just confirms our brief telephone con- versation today and agreement to dismiss the above- entitled case. I have enclosed a copy of the Stipulation for your information. Sincerely, VICTOR HARRIS VH:dc 1 VICTOR HARRIS, ESQ. NEIL GOTANDA, ESQ. 2 DIANE S. GREENBERG, ESQ. CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 3 115 Sansome Street San Francisco, California 94104 4 Telephone: (415) 421-3405 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 CASA JUSTICIA, et al., 11 ) ) Plaintiff, Civil No. 75-0219A-GT 12 ) ) 13 ) v . ) STIPULATION AND ORDER 14 ) ) JOHN DUFFY, etc., et al., 15 ) ) Defendants. ) 16 ) 17 Pursuant to Rule 41(a)(2), 18 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is hereby stipulated that the above-entitled 19 action may be dismissed, each party to bear its own costs. 20 Dated: December 28, 1977. 21 y VICTOR HARRIS, one 22 of the attorneys for Plaintiff CASA JUSTICIA 23 24 Donald L. Clark, County C,212E5e1 25 Dated: 26 LLOYD. M. HARMON, JR., Deputy, 27 Attorneys for Defendants 28 ORDER Based upon the Stipulation of the parties 29 hereto, and good cause appearing therefor: 30 IT IS SO ORDERED. 31 Dated: 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE LAW OFFICES OF CALIFORNIA RURAL LEGAL ASSISTANCE 328 CAYUGA STREET P.O. -

Xm and Air America Radio Announce Long Term Agreement; Xm to Be Official Satellite Radio Network of Air America

NEWS RELEASE XM AND AIR AMERICA RADIO ANNOUNCE LONG TERM AGREEMENT; XM TO BE OFFICIAL SATELLITE RADIO NETWORK OF AIR AMERICA 4/11/2005 Washington D.C., April 11, 2005 -- XM Satellite Radio (NASDAQ: XMSR), the nation's leading satellite radio provider with more than 3.77 million subscribers, has announced a new long-term agreement with Air America Radio, the national progressive entertainment talk radio network home to Al Franken, Randi Rhodes and Janeane Garofalo. As part of this agreement XM will be the official satellite radio network for Air America Radio. Beginning in May, XM's liberal talk channel, America Left (XM Channel 167) will be renamed Air America Radio. The channel will include an expanded line-up of Air America Radio programming, including the recently debuted "Springer on the Radio" hosted by Jerry Springer and upcoming "Rachel Maddow Show," among others. XM's Air America Radio channel also will feature popular shows currently carried on America Left, including "The Ed Shultz Show" and "The Alan Colmes Show." "XM was a natural fit to be the official satellite radio network of Air America Radio, given its large subscriber base, numerous distribution channels and demonstrated growth," said Danny Goldberg, CEO of Air America Radio. "The quality of XM's other partnerships, their Washington, D.C. location and proximity to the center of our nation's political workings, along with millions of subscribers, made our decision easy." XM's Washington, D.C. headquarters will offer dedicated studio space for special live broadcasts throughout the year for Air America Radio programs featuring Rachel Maddow, Marc Marron, Mark Riley, Al Franken, Katherine Lanpher, Jerry Springer, Randi Rhodes, Sam Seder, Janeane Garofalo, Chuck D, Mike Malloy, Laura Flanders, Steve Earle, Robert Kennedy Jr., Mike Papantonio, Kyle Jason, Marty Kaplan, and Betsy Rosenberg. -

Jaha's Promise' Shows How an Individual Can Make a Tremendous Difference in the Battle for Human Rights

To mark International Human Rights Defenders Day, the United Nations Regional Information Centre, the Human Rights Regional Office for Europe, and the European Union present: Jaha's P romise The screening will be introduced by Birgit Van Hout, Regional Representative for Europe, UN Human Rights Office, and will be followed by a panel discussion with: Patrick Farrelly Co-Director 'Jahar's Promise' Patrick worked with Michael Moore in the 1990s producing his award-winning satirical series, TV Nation and the Awful Truth. His 2005 HBO documentary ‘Left of the Dial’ (about the ill-fated launch in 2004 of the first liberal radio network, Air America featured Al Franken, Rachel Maddow, Marc Maron, and Janeane Garofalo) was an Emmy Award nominee. 'Voices from the Grave’, a film about the Northern Ireland Troubles won Ireland’s Best Documentary award in 2010. ‘Nuala’, a 2012 film he made about the Irish writer Nuala O’Faolain won Best Irish Film at the Dublin Film Festival and awards at the Vancouver and Palm Springs film festivals. Marjeta Jager Deputy-Director General for International Cooperation and Development, European Commission Marjeta is currently Deputy Director General in DG DEVCO. She has been working in the Commission since 2005, starting as Director for Security in DG TREN and later being Director for international energy and transport files and institutional affairs, as well as Head of Cabinet of the Transport Commissioner. Before joining the Commission, Marjeta was working since 1991 for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and she was the first Deputy Permanent Representative of Slovenia to the EU. -

THE KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS Volume 39, Number 76 Friday, September 24, 1999 U.S

Kwajalein Hourglass THE KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS Volume 39, Number 76 Friday, September 24, 1999 U.S. Army Kwajalein Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands Team NMD counts down to Oct. 3 IFT-3 By Jim Bennett The EKV sits atop a Lockheed- The folks on Meck enjoy their work. Martin Payload Launch Vehicle (PLV), Never mind that distinguished visi- which launches the payload, or EKV, tors from the states will closely watch into space. Once there, the EKV is the National Missile Defenses Inte- designed to seek out and strike an grated Flight Test-3 on Oct. 3. incoming reentry vehicle. The EKV; The men and women that make the Battle Command, Control and up Team NMD on Meck Island con- Communications Center (BMC3); the sist of 160 engineers, technicians, Ground Based Radar Prototype directors and staff. All simply want (GBR-P); and all the relevant sensors to hit a bullet with a bullet in the make up the National Missile De- Exo. fense (NMD) program. Congress Theres a lot of people with their named it a national priority this sum- hearts in this, said Ron Meyer, mer. Raytheons deputy program manager Were now a deployment pro- for the Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle gram, said Jim Hill, government (EKV). Meyer and his team of 28 EKV NMD site manager. This (EKV) is the specialists are among them. second prototype. Were trying to test Raytheon built the EKV at the the technology and what we need to companys Tuscon, Ariz., plant and do to deploy it. after a stopover at the Lockheed- The EKV program has already Martin plant in Sunnyvale, Calif., passed two data collection tests, but This Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle is delivered the bullet to Meck late this months shot will mark the first designed to seek out and destroy incoming last month. -

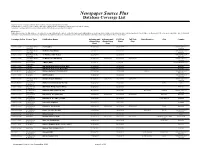

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text State/Province City Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Start Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover International 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Newspaper Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia All Staff Articles U.S. -

War Rites and Women's Rights

Smith ScholarWorks Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications Study of Women and Gender Spring 2005 Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth Armstrong Smith College, [email protected] Vijay Prashad Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Elisabeth and Prashad, Vijay, "Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights" (2005). Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs/22 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Author(s): Elisabeth B. Armstrong and Vijay Prashad Source: CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, terror wars (spring 2005), pp. 213- 253 Published by: Michigan State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41949472 Accessed: 14-01-2020 19:07 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Michigan State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to CR: The New Centennial Review This content downloaded from 131.229.19.247 on Tue, 14 Jan 2020 19:07:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Solidarity War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth b. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Age 46

ISSUE 72 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER AFI.com/Silver JULY 2–SEPTEMBER 16, 2015 ‘90s Cinema Now Best of the ‘80s Ingrid Bergman Centennial Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York Tell It Like It Is: Contents Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 ........................2 July 4–September 5 Keepin’ It Real: ‘90s Cinema Now ............4 In early 1968, William Greaves began shooting in Central Park, and the resulting film, SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM: TAKE ONE, came to be considered one of the major works of American independent cinema. Later that year, following Ingrid Bergman Centennial .......................9 a staff strike, WNET’s newly created program BLACK JOURNAL (with Greaves as executive producer) was established “under black editorial control,” becoming the first nationally syndicated newsmagazine of its kind, and home base for a Best of Totally Awesome: new generation of filmmakers redefining documentary. 1968 also marked the production of the first Hollywood studio film Great Films of the 1980s .....................13 directed by an African American, Gordon Park’s THE LEARNING TREE. Shortly thereafter, actor/playwright/screenwriter/ novelist Bill Gunn directed the studio-backed STOP, which remains unreleased by Warner Bros. to this day. Gunn, rejected Bugs Bunny 75th Anniversary ...............14 by the industry that had courted him, then directed the independent classic GANJA AND HESS, ushering in a new type of horror film — which Ishmael Reed called “what might be the country’s most intellectual and sophisticated horror films.” Calendar ............................................15 This survey is comprised of key films produced between 1968 and 1986, when Spike Lee’s first feature, the independently Special Engagements ............12-14, 16 produced SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT, was released theatrically — and followed by a new era of studio filmmaking by black directors.