Abraham Lincoln's Interest in Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Henry

MEMOIR JOSEPH HENRY. SIMON NEWCOMB. BEAD BEFORE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OP SCIENCES, APRIL 21, 1880. (1) BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH HENRY. In presenting to the Academy the following notice of its late lamented President the writer feels that an apology is due for the imperfect manner in which he has been obliged to perform the duty assigned him. The very richness of the material has been a source of embarrassment. Few have any conception of the breadth of the field occupied by Professor Henry's researches, or of the number of scientific enterprises of which he was either the originator or the effective supporter. What, under the cir- cumstances, could be said within a brief space to show what the world owes to him has already been so well said by others that it would be impracticable to make a really new presentation without writing a volume. The Philosophical Society of this city has issued two notices which together cover almost the whole ground that the writer feels competent to occupy. The one is a personal biography—the affectionate and eloquent tribute of an old and attached friend; the other an exhaustive analysis of his scientific labors by an honored member of the society well known for his philosophic acumen.* The Regents of the Smithsonian Institution made known their indebtedness to his administration in the memorial services held in his honor in the Halls of Congress. Under these circumstances the onl}*- practicable course has seemed to be to give a condensed resume of Professor Henry's life and works, by which any small occasional gaps in previous notices might be filled. -

Alexander Graham Bell 1847-1922

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XXIII FIRST MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL 1847-1922 BY HAROLD S. OSBORNE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1943 It was the intention that this Biographical Memoir would be written jointly by the present author and the late Dr. Bancroft Gherardi. The scope of the memoir and plan of work were laid out in cooperation with him, but Dr. Gherardi's untimely death prevented the proposed collaboration in writing the text. The author expresses his appreciation also of the help of members of the Bell family, particularly Dr. Gilbert Grosvenor, and of Mr. R. T. Barrett and Mr. A. M. Dowling of the American Telephone & Telegraph Company staff. The courtesy of these gentlemen has included, in addition to other help, making available to the author historic documents relating to the life of Alexander Graham Bell in the files of the National Geographic Society and in the Historical Museum of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL 1847-1922 BY HAROLD S. OSBORNE Alexander Graham Bell—teacher, scientist, inventor, gentle- man—was one whose life was devoted to the benefit of mankind with unusual success. Known throughout the world as the inventor of the telephone, he made also other inventions and scientific discoveries of first importance, greatly advanced the methods and practices for teaching the deaf and came to be admired and loved throughout the world for his accuracy of thought and expression, his rigid code of honor, punctilious courtesy, and unfailing generosity in helping others. -

Gustavus A. Hyde, Professor Espy's Volunteers, and the Development Ol

Bruce Sinclair Gustavus A. Hyde, Case Institute of Technology Professor Espy's volunteers, Cleveland, Ohio and the development ol systematic weather observation In December 1842, James P. Espy, meteorologist, some- time professor of mathematics for the U. S. Navy but better known as the "Storm King" for his theories on the cause of storms, issued a public call for volunteer weather observers. Addressed to the "Friends of Science," via the medium of newspapers throughout the country, Espy requested all those interested in weather phenom- ena to record meteorological data in their own localities and send him the information for use in testing his weather theories.1 One of the readers of Professor Espy's circular was Gustavus A. Hyde, a seventeen year old student at the Framingham, Massachusetts Academy. Fired with en- thusiasm for the new project "I wrote to him," Hyde later recalled, "and in return received blank slips on which to take my readings."2 He purchased a ther- mometer and together with a barn weather vane and a home-made rain gauge he began making a record of the weather. Hyde's zeal lasted for well over half a century, a record perhaps unmatched by any of the other volunteers who answered the call for their serv- ices. During the period of Hyde's career, meteorology advanced from the empirical compilation of amateur observations to a science, based on the interpretation of data systematically collected by professional meteor- ologists. Gustavus A. Hyde Espy's call for volunteers came at a time of particular interest in weather. His own theory of storms was in sharp conflict with that of William Redfield, another was triumphantly received in France. -

Alexander Graham Bell, Joseph Henry, and the “Empty Helix” Experiment

Alexander Graham Bell, Joseph Henry, and the “empty helix” experiment Varderes Barsegyan (Vardo), Gursimran Singh (Gary) Sethi, and Michael Littman Princeton University AAPT Summer Meeting 2015 1 Alexander Graham Bell visits Joseph Henry March 1-2, 1875 Joseph Henry (1797 – 1878) Alexander Bell (1847 – 1922) – First Secretary of Smithsonian (1846 – 1878); – Teacher of the deaf; Professor of Vocal Previously a Professor at Princeton College; Physiology at Boston University. In 1875, he is Early contributor to science of electro- figuring out how to send many telegraph messages magnetism. Contemporary of Ohm, Faraday, and on a single wire. His work follows the 1872 Ampere – electrical units are named after these invention of the duplex telegraph of Stearns. individuals. Alexander Graham Bell visits Joseph Henry March 1-2, 1875 Dear Mama and Papa, (letter of March 18, 1875) … Alexander Graham Bell visits Joseph Henry March 1-2, 1875 The “telephone” mentioned is a telegraphic device using tuned reeds Make and Break transmitter (at the vibration frequency of the iron reed) And matched receiver with a second iron reed resonantly excited by pulses Alexander Graham Bell visits Joseph Henry March 1-2, 1875 Alexander Graham Bell visits Joseph Henry March 1-2, 1875 6 Why does this work? Ampere’s observation that parallel wire with current in same direction attract Therefore when current is flowing in an empty helix, it contracts axially When current is pulsing, the empty helix pulses axially producing sound 7 What do we know about actual helix? In an earlier letter (Thanksgiving 1874) Bell describes the first observation of this effect – the coil consisted of No. -

Historical Perspective of Electricity

B - Circuit Lab rev.1.04 - December 19 SO Practice - 12-19-2020 Just remember, this test is supposed to be hard because everyone taking this test is really smart. Historical Perspective of Electricity 1. (1.00 pts) The first evidence of electricity in recorded human history was… A) in 1752 when Ben Franklin flew his kite in a lightning storm. B) in 1600 when William Gilbert published his book on magnetism. C) in 1708 when Charles-Augustin de Coulomb held a lecture stating that two bodies electrified of the same kind of Electricity exert force on each other. D) in 1799 when Alessandro Volta invented the voltaic pile which proved that electricity could be generated chemically. E) in 1776 when André-Marie Ampère invented the electric telegraph. F) about 2500 years ago when Thales of Miletus noticed that a piece of amber attracted straw or feathers when he rubbed it with cloth. 2. (3.00 pts) The word electric… (Mark ALL correct answers) A) was first used in printed text when it was published in William Gilber’s book on magnetism. B) comes from the Greek word ήλεκτρο (aka “electron”) meaning amber. C) adapted the meaning “charged with electricity” in the 1670s. D) was first used by Nicholas Callen in 1799 to describe mail transmitted over telegraph wires, “electric-mail” or “email”. E) was cast in stone by Greek emperor Julius Caesar when he knighted Archimedes for inventing the electric turning lathe. F) was first used by Michael Faraday when he described electromagnetic induction in 1791. 3. (5.00 pts) Which five people, who made scientific discoveries related to electricity, were alive at the same time? (Mark ALL correct answers) A) Charles-Augustin de Coulomb B) Alessandro Volta C) André-Marie Ampère D) Georg Simon Ohm E) Michael Faraday F) Gustav Robert Kirchhoff 4. -

Origin of the Electric Motor

Origin of the Electric Motor JOSEPH C. MIGHALOWICZ MEMBER AIEE HE DAY that man Had it not been for the efforts of men like 1821—Michael Faraday dem- T molded the first wheel Davenport, De Jacobi, and Page, the benefits onstrated for the first time the from the sledlike skids of his of the electric motor would not be enjoyed possibility of motion by electro- magnetic means with the move- primitive wagon should be today. It is the purpose of this article to trace ment of a magnetic needle in a one of great commemoration, briefly the early history of the science of electro- field of force. had not its identity been lost motion and, in particular, to bring to light and 1829—-Joseph Henry, a teacher in the passing of time. Not to honor the inventor of the electric motor. of physics at the Albany Academy unlike the wheel and prob- in New York, constructed an elec- ably second only to the wheel, tromagnetic oscillating motor but considered it only a "philosophical the electric motor has been a toy." great benefactor to man and its history, too, slowly is 1833—Joseph Saxton, an American inventor, exhibited a magneto- being forgotten. Today, we hear very little, if anything, about Thomas Figure 1. Thomas Davenport, the blacksmith who invented the electric Davenport, inven- motor; or about De Jacobi, who propelled the first boat tor of the electric by means of an electric motor; or of Charles Page who motor successfully carried passengers on the first practical electric railway. Had it not been for the efforts of these men and others like them, the benefits of the electric motor probably would not be enjoyed today. -

History of Magnetism and Electricity History of Magnetism and Electricity

History of Magnetism and Electricity History of Magnetism and Electricity ● As the result of successfully completing this unit, the students will – Discuss the historical background of electricity, electromagnetism, and circuits – Compare and Contrast the time frame needed to discover the basic laws of electromagnetism and the time frame this course is taking to introduce those same concepts to the students Static Electricity – Thales from Milet ● Ca 600 BC ● Amber rubbed will attract light objects sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thales.jpg Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity Static Electricity – Thales from Milet ● Ca 600 BC ● Amber rubbed will attract light objects sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thales.jpg Static Electricity – Thales from Milet ● Ca 600 BC ● Amber rubbed will attract light objects ● ηλεκτρον (greek for amber) sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thales.jpg Static Electricity η λ ε κ τ ρ ο ν η = Eta λ = Lambda ε = Epsilon κ = Kappa τ = Tau ρ = Rho ο = Omega ν = Nu Static Electricity η λ ε κ τ ρ ο ν η = E E L E K T R O N λ = L ε = E κ = K τ = T ρ = R ο = O ν = N Static Electricity – Thales from Milet ● Ca 600 BC ● Amber rubbed will attract light objects ● ηλεκτρον (greek for amber) → electron sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thales.jpg William Gilbert - Magnetism ● 1600 sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:William_Gilbert.jpg http://www.solarnavigator.net/compass.htm http://www.physics.ubc.ca/~outreach/phys420/p420_01/shaun/shaun/why_it_works.htm -

Applied Electromagnetics

Dan Sievenpiper - UCSD, 858-822-6678,[email protected] Applied Electromagnetics Dan Sievenpiper, 2018-10-29 1 Dan Sievenpiper - UCSD, 858-822-6678,[email protected] History: A Few of the Early Pioneers in Electromagnetics Andre-Marie Ampere Michael Faraday James C. Maxwell Heinrich Hertz Invented telegraph Invented electric motor Unified electricity, magnetism Proved existence of (among many other things) (among many other things) and light into one theory electromagnetic waves Guglielmo Many, many others: Nicola Tesla Marconi • Alessandro Volta • James Prescott Joule • Georg Simon Ohm • Charles William Siemens • Charles-Augustin Coulomb • Joseph Henry • Wilhelm Eduard Weber • Hans Christian Orsted Invented AC, wireless Invented radio • … communication 2 power transfer Dan Sievenpiper - UCSD, 858-822-6678,[email protected] Courses in Applied Electromagnetics • Undergrad Courses – ECE107 – Electromagnetism – ECE123 – Antenna Systems Engineering – ECE166 – Microwave Systems and Circuits – ECE182 – Electromagnetic Optics, Guided-wave and Fiber Optics • Graduate Courses – ECE221 – Magnetic Materials Principles and Applications – ECE222A – Antennas and their System Applications – ECE222B – Electromagnetic Theory – ECE222C – Computational Methods for Electromagnetics – ECE222D – Advanced Antenna Design 3 Dan Sievenpiper - UCSD, 858-822-6678,[email protected] ECE107 Electromagnetism • Electrostatics, magnetostatics • Vector analysis • Maxwell’s equations • Plane waves, reflection, refraction • Electromagnetic -

Lindley, D., Never at Rest, American Scientist, 96, 504-508

Never at Rest » American Scientist http://www.americanscientist.org/bookshelf/id.4826,content.true,cs... BOOK REVIEW Never at Rest David Lindley KELVIN: Life, Labours and Legacy. Edited by Raymond Flood, Mark McCartney and Andrew Whitaker. 376 pp. Oxford University Press, 2008. $110. Lord Kelvin, especially in the last decades of his long life, was a genuine celebrity. Beyond his achievements in science, he had gained prominence for his forays into industrial engineering—his efforts were crucial to the success of the transatlantic telegraph cable—and had established himself as one of the earliest examples of what we might call a technologist, a man who applied scientific principles to commercial ventures. He made himself wealthy in the process, rose to the peerage and traveled widely. His visits to North America were noted on the front page of the New York Times and other newspapers, and reporters eagerly sought out his views—which he was equally eager to supply—on science, industry, commerce, even politics. On his death in 1907, at the age of 83, he was interred next to Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey, to reside forever alongside perhaps the most supreme mind of science. But how quickly his star faded! To be sure, he died just as the emergence of radioactivity, quantum theory and relativity transformed physics, but still, we remember and celebrate such contemporaries of Kelvin as James Clerk Maxwell, Michael Faraday, James Prescott Joule and Ludwig Boltzmann. In his day, Kelvin was far better known than any of them, but in 1999, when the U.K. Institute of Physics polled its members for the top physicists of all time, Kelvin didn't even crack the top 30. -

Joseph Henry Developed Electromagnetic Induction

JOSEPH HENRY DEVELOPED ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION b y Brian Roberts, CIBSE Heritage G r oup Joseph Henry, 1797 - 1878 Henry was born in Albany, New York State on 17 th December, 1 797 , to Scottish immigrants William Henry and Ann Alexander Henry. His par ents were poor and his father died while he was still young. Henry lived for the rest of his childhood with his grandmother in Galway, New York and went to a school which would later be named in his honour as the “Joseph Henry Elementary School.” After sc hool he worked in a general store. At the age of thirteen he was apprenticed to a watchmaker and silver smith, but his first love was the theatre and he considered becoming a professional actor. First Presbyterian Church of Albany, New York Stat e, where Joseph Henry was baptised in 1798 (Smithsonian Archives) The Albany Academy (Smithsonian Archives) The Albany Academy photographed in 1907 However, in about 1810, after reading a book Popular Lectures on Experimental Philosophy he be came interested in science. In 1819 he entered The Albany Academy where, in spite of receiving free tuition, he was so poor that he had to support himself by various teaching positions. He planned to enter the medical profession, but in 1824 he was appoint ed Assistant Engineer for the survey of the State road, then being constructed between the Hudson River and L ake Erie. In 1826, Henry was appointed Professor of Mathematics & Natural Philosophy at The Albany Academy, because not only did he excel at his studies, but he often helped his teachers teach science. -

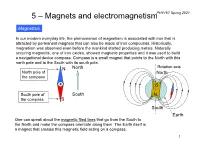

5 – Magnets and Electromagnetismphy167 Spring 2021

5 – Magnets and electromagnetismPHY167 Spring 2021 Magnetism In our modern everyday life, the phenomenon of magnetism is associated with iron that is attracted by permanent magnets that can also be made of iron compounds. Historically, magnetism was observed even before the mankind started producing metals. Naturally occuring magnetite, one of iron oxides, showed magnetic properties and it was used to build a navigational device compass. Compass is a small magnet that points to the North with this north pole and to the South with its south pole. N North Rotation axis North pole of North the compass South pole of South the compass S South Earth One can speak about the magnetic filed lines that go from the South to the North and make the compass orientate along them. The Earth itself is a magnet that creates this magnetic field acting on a compass. 1 Compass is an example of a magnetic dipole, that is, two magnetic poles at a distance from each other Analogy between magnetic and electric dipoles Magnetic N S S N N S N S - + - + Electric - + + - Two unlike poles attract each other Two like poles repel each other Torque on magnetic and electric dipoles: N S 2 Magnetic field B Electric field E Magnetic poles interact similarly to electric poles (charges). Coulomb first established his Coulomb’s law for magnetic poles that were located at the ends of long and thin magnetized stabs: In was easier to experiment of magnetic poles then on electric charges. N S Analogy between electrostatics and magnetism is incomplete because one cannot isolate magnetic poles. -

The Ampère House and the Museum of Electricity, Poleymieux Au Mont D’Or, France (Near Lyon)

The Ampère House The Ampère House and the Museum of Electricity, Poleymieux au Mont d’Or, France (Near Lyon). André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) Ampere at 21 Ampere at 39 Ampere at 55 Location: Poleymieux au Mont d’Or Compound of the Ampere Family Location: Poleymieux au Mont d’Or Compound of the Ampere Family Educated based on Rousseau theories directly by his father, Jean-Jacques. Never went to school. A genius as soon as 13 years old. A “Prodigy child” learn Latin and other languages. Teach himself the works of Bernouilli and Euler in Latin. Professor of Mathematics, Italian, Chemistry, Mathematics and Physics at 22. Member of the Academy in 1814 (39 years old). Entrance room: History of the Museum Poleymieux au Mont d’Or André-Marie lived there from 7 to 20 years old. His wife and his child stay there a few more years. Museum inaugurated on July 1, 1931. Picture of Hernand & Sosthenes Behn, re-purchased the house to make a museum (Founders of ITT in the USA in 1920). They were from a French Mother and Danish Father. Studied in France and emigrated to New York after graduation. Gave as a gift to the SFE (Société Française des Electriciens) in 1928. Hernand died in France in 1933 in a retirement villa. Room of the Three Amperes. The House of Ampère -Partners Curator: Mr. Georges Asch Plate on the life of Ampere. Definitions (ANSI/IEEE Std 100) Ampere (1) (metric practice). That constant current which, if maintained in two straight parallel conductors of infinite length, of negligible circular cross section, F F and placed at one meter apart in vacuum, would produce between these conductors a force equal to 2x10-7 newton per meter of length (Adopted by the 9th General Conference on Weight and 1 meter Measures in 1948).