Alexander Graham Bell 1847-1922

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2017 News for Descendants of Johann Christopher Windemuth B

January 2017 News for descendants of Johann Christopher Windemuth b. 1676 Windemuth Family Newsletter Related Family Names: Windemuth*Wintamote*Wintamute*Wintemute*Wintermote*Wintermute*Wintermuth Nancy Lane Washington D.C. Debutante 4th Great Granddaughter of Georg Philip Windemuth Nancy Lane grew up in Washington D.C. when President Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were in office. Her father Franklin Knight Lane, was a commissioner and then Chairmen of the Interstate Commerce Commission. He was then appointed as the 26th Secretary of the Interior by President Wilson. Nancy was born on January 4, 1903 to Anna Clair Wintermute and Franklin Knight Lane, in Los Angeles, California. Her older bother Franklin Knight Lane Jr. was born April 5, 1896 in San Francisco, California. Nancy’s father, Franklin Knight Lane, was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Is- land in 1864 and her mother Anna Clair Wintermute born in Ontario, Canada in 1870. Her parent’s were married in Tacoma Washington in 1893 where Franklin Lane was Nancy Lane editor and part owner of the Tacoma Newspaper. Franklin and Anna early life was in Washington D.C. 1918 San Francisco where Franklin was practicing law with is bother. He became San Fran- cisco’s District Attorney and also ran for Governor of California 1902, but lost. Continued on Page 3 Inside this issue: Coming Soon Welcome to Cape Breton 2 Nancy Lane 3 Windemuth Family Reunion Nancy Lane 4 Reunion Registration 5 ****July 10-13, 2017**** Reunion Itinerary 6 This is a great opportunity to renew friendships Heritage Books and 7 With cousins and meet new ones Officers Missing Members 8 Registration forms Life Members 9 are on page 5 and 6 Membership Payments © 2016 Windemuth Family Organization Windemuth Family Newsletter Page 2 January 2017 Welcome to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia by Norma (Wintermute) Marchant Once you arrive in Cape Breton, you will see the phrase, “Ciad Mille Failte!” on signage throughout the island. -

Celtic-Colours-Guide-2019-1

11-19 October 2019 • Cape Breton Island Festival Guide e l ù t h a s a n ò l l g r a t e i i d i r h . a g L s i i s k l e i t a h h e t ò o e c b e , a n n i a t h h a m t o s d u o r e r s o u ’ a n d n s n a o u r r a t I l . s u y l c a g n r a d e h , n t c e , u l n l u t i f u e r h l e t i u h E o e y r r e h a t i i s w d h e e e d v i p l , a a v d i b n r a a t n h c a e t r i a u c ’ a a h t a n a u h c ’ a s i r h c a t l o C WELCOME Message from the Atlantic Canada Message de l’Agence de promotion A Message from the Honourable Opportunities Agency économique du Canada atlantique Stephen McNeil, M.L.A. Premier Welcome to the 2019 Celtic Colours Bienvenue au Celtic Colours On behalf of the Province of Nova International Festival International Festival 2019 Scotia, I am delighted to welcome you to the 2019 Celtic Colours International Tourism is a vital part of the Atlantic Le tourisme est une composante Festival. -

Wireless Networks

SUBJECT WIRELESS NETWORKS SESSION 2 WIRELESS Cellular Concepts and Designs" SESSION 2 Wireless A handheld marine radio. Part of a series on Antennas Common types[show] Components[show] Systems[hide] Antenna farm Amateur radio Cellular network Hotspot Municipal wireless network Radio Radio masts and towers Wi-Fi 1 Wireless Safety and regulation[show] Radiation sources / regions[show] Characteristics[show] Techniques[show] V T E Wireless communication is the transfer of information between two or more points that are not connected by an electrical conductor. The most common wireless technologies use radio. With radio waves distances can be short, such as a few meters for television or as far as thousands or even millions of kilometers for deep-space radio communications. It encompasses various types of fixed, mobile, and portable applications, including two-way radios, cellular telephones, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and wireless networking. Other examples of applications of radio wireless technology include GPS units, garage door openers, wireless computer mice,keyboards and headsets, headphones, radio receivers, satellite television, broadcast television and cordless telephones. Somewhat less common methods of achieving wireless communications include the use of other electromagnetic wireless technologies, such as light, magnetic, or electric fields or the use of sound. Contents [hide] 1 Introduction 2 History o 2.1 Photophone o 2.2 Early wireless work o 2.3 Radio 3 Modes o 3.1 Radio o 3.2 Free-space optical o 3.3 -

Autumn 2018, Vol

www.telcomhistory.org (303) 296‐1221 Autumn 2018, Vol. 23, no.3 Jody Georgeson, editor A Message from Our Director As I write this, Summer is coming to a close and you can feel the change of the seasons in the air. Kids are going Back to school, nights are getting cooler, leaves are starting to turn and soon our days will Be filled with holiday celeBrations. We have a lot to Be thankful for. We had a great celeBration in July at our Seattle Connections Museum. Visitors joined us from near and far for our Open House. We are grateful to all the volunteers and Seattle Board memBers for their hard work and dedication in making this a successful event. Be sure to read more about the new exhiBit that was dedicated in honor of our late Seattle curator, Don Ostrand, in this issue. I would also like to thank our partners at Telephone Collectors International (TCI) and JKL Museum who traveled from California to help us celeBrate. As always, we welcome anyone who wants to visit either of our locations or to volunteer to help preserve the history of the telecommunications industry. Visit our website at www.telcomhistory.org for more information. Enjoy the remainder of 2018. Warm regards, Lisa Berquist Executive Director Ostrand Collection Ribbon-cutting at Connections Museum Seattle! By Dave Dintenfass A special riBBon-cutting celeBration took place on 14 July 2018 at Connections Museum Seattle. This marked the opening of a special room to display the Ostrand Collection. This collection, on loan from the family of our late curator Don Ostrand, contains unusual items not featured elsewhere in our museum. -

Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Alexander Melville Bell, February 26, 1880, with Transcript

Library of Congress Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Alexander Melville Bell, February 26, 1880, with transcript ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL TO HIS FATHER A. MELVILLE BELL 904 14th Street, N. W., Washington, D. C. Feb. 26th, 1880. Dear Papa: I have just written to Mamma about Mabel's baby and I now write to you about my own! Only think! — Two babies in one week! The first born at 904 14th Street — on the fifteenth inst., the other at my laboratory on the nineteenth. Both strong vigorous healthy young things and both destined I trust to grow into something great in the future. Mabel's baby was light enough at birth but mine was LIGHT ITSELF! Mabel's baby screamed inarticulately but mine spoke with distinct enunciation from the first. I have heard articulate speech produced by sunlight! I have heard a ray of the sun laugh and cough and sing! The dream of the past year has become a reality — the “ Photophone ” is an accomplished fact. I am not prepared at present to go into particulars and can only say that with Mr. Tainter's assistance I have succeeded in preparing crystalline selenium of so low a resistance and so sensitive to light that we have been enabled to perceive variations of light as sounds in the telephone. In this way I have been able to hear a shadow, and I have even perceived by ear the passage of a cloud across the sun's disk. Can Imagination picture what the future of this invention is to be! I dream of so many important and wonderful applications that I cannot bring myself to make known my discovery — until I have demonstrated the practicability of some of these schemes. -

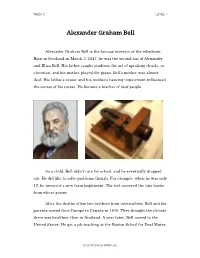

Alexander Graham Bell

WEEK 2 LEVEL 7 Alexander Graham Bell Alexander Graham Bell is the famous inventor of the telephone. Born in Scotland on March 3, 1847, he was the second son of Alexander and Eliza Bell. His father taught students the art of speaking clearly, or elocution, and his mother played the piano. Bell’s mother was almost deaf. His father’s career and his mother’s hearing impairment influenced the course of his career. He became a teacher of deaf people. As a child, Bell didn’t care for school, and he eventually dropped out. He did like to solve problems though. For example, when he was only 12, he invented a new farm implement. The tool removed the tiny husks from wheat grains. After the deaths of his two brothers from tuberculosis, Bell and his parents moved from Europe to Canada in 1870. They thought the climate there was healthier than in Scotland. A year later, Bell moved to the United States. He got a job teaching at the Boston School for Deaf Mutes. © 2019 Scholar Within, Inc. WEEK 2 LEVEL 7 One of his students was a 15-year-old named Mabel Hubbard. He was 10 years older than she was, but they fell in love and married in 1877. The Bells raised two daughters but lost two sons who both died as babies. Bell’s father-in-law, Gardiner Hubbard, knew Bell was interested in inventing things, so he asked him to improve the telegraph. Telegraph messages were tapped out with a machine using dots and dashes known as Morse code. -

3.6Mb PDF File

Be sure to visit all the National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia: • Halifax Citadel National • Historic Site of Canada Prince of Wales Tower National • Historic Site of Canada York Redoubt National Historic • Site of Canada Fort McNab National Historic • Site of Canada Georges Island National • Historic Site of Canada Grand-Pré National Historic • Site of Canada Fort Edward National • Historic Site of Canada New England Planters Exhibit • • Port-Royal National Historic Kejimkujik National Park of Canada – Seaside • Site of Canada • Fort The Bank Fishery/Age of Sail Exhibit • Historic Site of Canada • Melanson SettlementAnne National Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site National Historic Site of Canada • of Canada • Kejimkujik National Park and Marconi National Historic National Historic Site of Canada • Site of Canada Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of • Canada Canso Islands National • Historic Site of Canada St. Peters Canal National • Historic Site of Canada Cape Breton Highlands National Park/Cabot T National Parks and National Historic rail Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia See inside for details on great things to see and do year-round in Nova Scotia including camping, hiking, interpretation activities and more! Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best Planning Your Visit to the National Parks and Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada's history National Historic Sites of Canada and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is To receive FREE trip-planning information on the celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. -

The Stage Is Set

The Stage Is Set: Developments before 1900 Leading to Practical Wireless Communication Darrel T. Emerson National Radio Astronomy Observatory1, 949 N. Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721 In 1909, Guglielmo Marconi and Carl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy." In the Nobel Prize Presentation Speech by the President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences [1], tribute was first paid to the earlier theorists and experimentalists. “It was Faraday with his unique penetrating power of mind, who first suspected a close connection between the phenomena of light and electricity, and it was Maxwell who transformed his bold concepts and thoughts into mathematical language, and finally, it was Hertz who through his classical experiments showed that the new ideas as to the nature of electricity and light had a real basis in fact.” These and many other scientists set the stage for the rapid development of wireless communication starting in the last decade of the 19th century. I. INTRODUCTION A key factor in the development of wireless communication, as opposed to pure research into the science of electromagnetic waves and phenomena, was simply the motivation to make it work. More than anyone else, Marconi was to provide that. However, for the possibility of wireless communication to be treated as a serious possibility in the first place and for it to be able to develop, there had to be an adequate theoretical and technological background. Electromagnetic theory, itself based on earlier experiment and theory, had to be sufficiently developed that 1. -

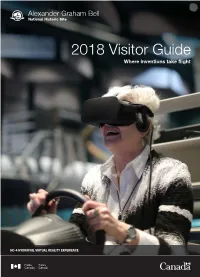

2018 Visitor Guide Where Inventions Take flight

2018 Visitor Guide Where inventions take flight HD-4 HYDROFOIL VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCE How to reach us Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site 559 Chebucto St (Route 205) Baddeck, Nova Scotia Canada 902-295-2069 [email protected] parkscanada.gc.ca/bell Follow us Welcome to Alexander Graham Bell /AGBNHS National Historic Site @ParksCanada_NS Imagine when travel and global communications as we know them were just a dream. How did we move from that reality to @parks.canada one where communication is instantaneous and globetrotting is an everyday event? Alexander Graham Bell was a communication and transportation pioneer, as well as a teacher, family man and humanitarian. /ParksCanadaAgency Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site is an architecturally unique exhibit complex where models, replicas, photo displays, artifacts and films describe the fascinating life and work of Alexander Hours of operation Graham Bell. Programs such as our White Glove Tours complement May 18 – October 30, 2018 the exhibits at the site, which is situated on ten hectares of land 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. overlooking Baddeck Bay and Beinn Bhreagh peninsula, the location of the Bells’ summer home. Entrance fees In the words of Bell, a born inventor Adult: $7.80 “Wealth and fame are coveted by all men, but the hope of wealth or the desire for fame will never make an inventor…you may take away all that he has, Senior: $6.55 and he will go on inventing. He can no more help inventing than he can help Youth: free thinking or breathing. Inventors are born — not made.” — Alexander Graham Bell Starting January 1, 2018, admission to all Parks Canada places for youth 17 and under is free! There’s no better time to create lasting memories with the whole family. -

Southwestern Bell Telephone Company Tariff F.C.C

SOUTHWESTERN BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY TARIFF F.C.C. NO. 67 2nd Revised Title Page Cancels 1st Revised Title Page INTERSTATE IntraLATA MESSAGE TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICE REGULATIONS AND SCHEDULES OF CHARGES Applying to interstate service between points WITHIN THE LATAs of the Southwestern Bell Telephone Company as hereinafter defined, to which Interstate IntraLATA Message Telecommunications Service is available. Interstate IntraLATA Message Telecommunications Service is furnished by means of wire, radio, or a combination thereof. (This page filed under Transmittal No. 2526) Issued: January 11, 1996 Effective: February 25, 1996 Edward A. Mueller (T) President and Chief Executive Officer - Southwestern Bell Telephone Company One Bell Center, St. Louis, MO 63101 (T) SOUTHWESTERN BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY Supplement No. 7 to TARIFF F.C.C. NO. 67 Page 1 of 1 ACCESS SERVICE The Bureau's Memorandum Opinion and Order in the Matter of 1997 Annual Access Tariff Filings; National Exchange Carrier Association Universal Service Fund and Lifeline Assistance Rates (1997 Annual Access Filing Compliance Order), released June 27, 1997, orders the following: -rate elements reflecting base factor portion forecasts, equal access exogenous cost changes, and growth factor calculations are suspended for one day and subject to an investigation. Pursuant to the 1997 Annual Access Filing Compliance Order (DA 97-1350), tariff revisions filed in Transmittal No. 2640, reflecting the aforementioned issues, and found on the following tariff pages are advanced one day to June 30, 1997 and then suspended one day to July 1, 1997. Number of Number of Number of Revision Revision Revision Except as Except as Except as Page Indicated Page Indicated Page Indicated 105b 4th (This page filed under Transmittal No. -

Joseph Henry

MEMOIR JOSEPH HENRY. SIMON NEWCOMB. BEAD BEFORE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OP SCIENCES, APRIL 21, 1880. (1) BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH HENRY. In presenting to the Academy the following notice of its late lamented President the writer feels that an apology is due for the imperfect manner in which he has been obliged to perform the duty assigned him. The very richness of the material has been a source of embarrassment. Few have any conception of the breadth of the field occupied by Professor Henry's researches, or of the number of scientific enterprises of which he was either the originator or the effective supporter. What, under the cir- cumstances, could be said within a brief space to show what the world owes to him has already been so well said by others that it would be impracticable to make a really new presentation without writing a volume. The Philosophical Society of this city has issued two notices which together cover almost the whole ground that the writer feels competent to occupy. The one is a personal biography—the affectionate and eloquent tribute of an old and attached friend; the other an exhaustive analysis of his scientific labors by an honored member of the society well known for his philosophic acumen.* The Regents of the Smithsonian Institution made known their indebtedness to his administration in the memorial services held in his honor in the Halls of Congress. Under these circumstances the onl}*- practicable course has seemed to be to give a condensed resume of Professor Henry's life and works, by which any small occasional gaps in previous notices might be filled. -

Bell Telephone Magazine

»y{iiuiiLviiitiJjitAi.¥A^»yj|tiAt^^ p?fsiJ i »^'iiy{i Hound / \T—^^, n ••J Period icsl Hansiasf Cttp public Hibrarp This Volume is for 5j I REFERENCE USE ONLY I From the collection of the ^ m o PreTinger a V IjJJibrary San Francisco, California 2008 I '. .':>;•.' '•, '•,.L:'',;j •', • .v, ;; Index to tne;i:'A ";.""' ;•;'!!••.'.•' Bell Telephone Magazine Volume XXVI, 1947 Information Department AMERICAN TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY New York 7, N. Y. PRINTKD IN U. S. A. — BELL TELEPHONE MAGAZINE VOLUME XXVI, 1947 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPRING, 1947 The Teacher, by A. M . Sullivan 3 A Tribute to Alexander Graham Bell, by Walter S. Gifford 4 Mr. Bell and Bell Laboratories, by Oliver E. Buckley 6 Two Men and a Piece of Wire and faith 12 The Pioneers and the First Pioneer 21 The Bell Centennial in the Press 25 Helen Keller and Dr. Bell 29 The First Twenty-Five Years, by The Editors 30 America Is Calling, by IVilliani G. Thompson 35 Preparing Histories of the Telephone Business, by Samuel T. Gushing 52 Preparing a History of the Telephone in Connecticut, by Edward M. Folev, Jr 56 Who's Who & What's What 67 SUMMER, 1947 The Responsibility of Managcincnt in the r^)e!I System, by Walter S. Gifford .'. 70 Helping Customers Improve Telephone Usage Habits, by Justin E. Hoy 72 Employees Enjoy more than 70 Out-of-hour Activities, by /()/;// (/. Simmons *^I Keeping Our Automotive Equipment Modern. l)y Temf^le G. Smith 90 Mark Twain and the Telephone 100 0"^ Crossed Wireless ^ Twenty-five Years Ago in the Bell Telephone Quarterly 105 Who's Who & What's What 107 3 i3(J5'MT' SEP 1 5 1949 BELL TELEPHONE MAGAZINE INDEX.