An Introduction to Analytical Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

A Brief History and Philosophy of Mechanics

A Brief History and Philosophy of Mechanics S. A. Gadsden McMaster University, [email protected] 1. Introduction During this period, several clever inventions were created. Some of these were Archimedes screw, Hero of Mechanics is a branch of physics that deals with the Alexandria’s aeolipile (steam engine), the catapult and interaction of forces on a physical body and its trebuchet, the crossbow, pulley systems, odometer, environment. Many scholars consider the field to be a clockwork, and a rolling-element bearing (used in precursor to modern physics. The laws of mechanics Roman ships). [5] Although mechanical inventions apply to many different microscopic and macroscopic were being made at an accelerated rate, it wasn’t until objects—ranging from the motion of electrons to the after the Middle Ages when classical mechanics orbital patterns of galaxies. [1] developed. Attempting to understand the underlying principles of 3. Classical Period (1500 – 1900 AD) the universe is certainly a daunting task. It is therefore no surprise that the development of ‘idea and thought’ Classical mechanics had many contributors, although took many centuries, and bordered many different the most notable ones were Galileo, Huygens, Kepler, fields—atomism, metaphysics, religion, mathematics, Descartes and Newton. “They showed that objects and mechanics. The history of mechanics can be move according to certain rules, and these rules were divided into three main periods: antiquity, classical, and stated in the forms of laws of motion.” [1] quantum. The most famous of these laws were Newton’s Laws of 2. Period of Antiquity (800 BC – 500 AD) Motion, which accurately describe the relationships between force, velocity, and acceleration on a body. -

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

Engineering Physics I Syllabus COURSE IDENTIFICATION Course

Engineering Physics I Syllabus COURSE IDENTIFICATION Course Prefix/Number PHYS 104 Course Title Engineering Physics I Division Applied Science Division Program Physics Credit Hours 4 credit hours Revision Date Fall 2010 Assessment Goal per Outcome(s) 70% INSTRUCTION CLASSIFICATION Academic COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is the first semester of a calculus-based physics course primarily intended for engineering and science majors. Course work includes studying forces and motion, and the properties of matter and heat. Topics will include motion in one, two, and three dimensions, mechanical equilibrium, momentum, energy, rotational motion and dynamics, periodic motion, and conservation laws. The laboratory (taken concurrently) presents exercises that are designed to reinforce the concepts presented and discussed during the lectures. PREREQUISITES AND/OR CO-RECQUISITES MATH 150 Analytic Geometry and Calculus I The engineering student should also be proficient in algebra and trigonometry. Concurrent with Phys. 140 Engineering Physics I Laboratory COURSE TEXT *The official list of textbooks and materials for this course are found on Inside NC. • COLLEGE PHYSICS, 2nd Ed. By Giambattista, Richardson, and Richardson, McGraw-Hill, 2007. • Additionally, the student must have a scientific calculator with trigonometric functions. COURSE OUTCOMES • To understand and be able to apply the principles of classical Newtonian mechanics. • To effectively communicate classical mechanics concepts and solutions to problems, both in written English and through mathematics. • To be able to apply critical thinking and problem solving skills in the application of classical mechanics. To demonstrate successfully accomplishing the course outcomes, the student should be able to: 1) Demonstrate knowledge of physical concepts by their application in problem solving. -

Hamiltonian Chaos

Hamiltonian Chaos Niraj Srivastava, Charles Kaufman, and Gerhard M¨uller Department of Physics, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI 02881-0817. Cartesian coordinates, generalized coordinates, canonical coordinates, and, if you can solve the problem, action-angle coordinates. That is not a sentence, but it is classical mechanics in a nutshell. You did mechanics in Cartesian coordinates in introductory physics, probably learned generalized coordinates in your junior year, went on to graduate school to hear about canonical coordinates, and were shown how to solve a Hamiltonian problem by finding the action-angle coordinates. Perhaps you saw the action-angle coordinates exhibited for the harmonic oscillator, and were left with the impression that you (or somebody) could find them for any problem. Well, you now do not have to feel badly if you cannot find them. They probably do not exist! Laplace said, standing on Newton’s shoulders, “Tell me the force and where we are, and I will predict the future!” That claim translates into an important theorem about differential equations—the uniqueness of solutions for given ini- tial conditions. It turned out to be an elusive claim, but it was not until more than 150 years after Laplace that this elusiveness was fully appreciated. In fact, we are still in the process of learning to concede that the proven existence of a solution does not guarantee that we can actually determine that solution. In other words, deterministic time evolution does not guarantee pre- dictability. Deterministic unpredictability or deterministic randomness is the essence of chaos. Mechanical systems whose equations of motion show symp- toms of this disease are termed nonintegrable. -

Chapter 5 the Relativistic Point Particle

Chapter 5 The Relativistic Point Particle To formulate the dynamics of a system we can write either the equations of motion, or alternatively, an action. In the case of the relativistic point par- ticle, it is rather easy to write the equations of motion. But the action is so physical and geometrical that it is worth pursuing in its own right. More importantly, while it is difficult to guess the equations of motion for the rela- tivistic string, the action is a natural generalization of the relativistic particle action that we will study in this chapter. We conclude with a discussion of the charged relativistic particle. 5.1 Action for a relativistic point particle How can we find the action S that governs the dynamics of a free relativis- tic particle? To get started we first think about units. The action is the Lagrangian integrated over time, so the units of action are just the units of the Lagrangian multiplied by the units of time. The Lagrangian has units of energy, so the units of action are L2 ML2 [S]=M T = . (5.1.1) T 2 T Recall that the action Snr for a free non-relativistic particle is given by the time integral of the kinetic energy: 1 dx S = mv2(t) dt , v2 ≡ v · v, v = . (5.1.2) nr 2 dt 105 106 CHAPTER 5. THE RELATIVISTIC POINT PARTICLE The equation of motion following by Hamilton’s principle is dv =0. (5.1.3) dt The free particle moves with constant velocity and that is the end of the story. -

1 the Basic Set-Up 2 Poisson Brackets

MATHEMATICS 7302 (Analytical Dynamics) YEAR 2016–2017, TERM 2 HANDOUT #12: THE HAMILTONIAN APPROACH TO MECHANICS These notes are intended to be read as a supplement to the handout from Gregory, Classical Mechanics, Chapter 14. 1 The basic set-up I assume that you have already studied Gregory, Sections 14.1–14.4. The following is intended only as a succinct summary. We are considering a system whose equations of motion are written in Hamiltonian form. This means that: 1. The phase space of the system is parametrized by canonical coordinates q =(q1,...,qn) and p =(p1,...,pn). 2. We are given a Hamiltonian function H(q, p, t). 3. The dynamics of the system is given by Hamilton’s equations of motion ∂H q˙i = (1a) ∂pi ∂H p˙i = − (1b) ∂qi for i =1,...,n. In these notes we will consider some deeper aspects of Hamiltonian dynamics. 2 Poisson brackets Let us start by considering an arbitrary function f(q, p, t). Then its time evolution is given by n df ∂f ∂f ∂f = q˙ + p˙ + (2a) dt ∂q i ∂p i ∂t i=1 i i X n ∂f ∂H ∂f ∂H ∂f = − + (2b) ∂q ∂p ∂p ∂q ∂t i=1 i i i i X 1 where the first equality used the definition of total time derivative together with the chain rule, and the second equality used Hamilton’s equations of motion. The formula (2b) suggests that we make a more general definition. Let f(q, p, t) and g(q, p, t) be any two functions; we then define their Poisson bracket {f,g} to be n def ∂f ∂g ∂f ∂g {f,g} = − . -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

Integrals of Motion Key Point #15 from Bachelor Course

KeyKey12-10-07 see PointPoint http://www.strw.leidenuniv.nl/˜ #15#10 fromfrom franx/college/ BachelorBachelor mf-sts-07-c4-5 Course:Course:12-10-07 see http://www.strw.leidenuniv.nl/˜ IntegralsIntegrals ofof franx/college/ MotionMotion mf-sts-07-c4-6 4.2 Constants and Integrals of motion Integrals (BT 3.1 p 110-113) Much harder to define. E.g.: 1 2 Energy (all static potentials): E(⃗x,⃗v)= 2 v + Φ First, we define the 6 dimensional “phase space” coor- dinates (⃗x,⃗v). They are conveniently used to describe Lz (axisymmetric potentials) the motions of stars. Now we introduce: L⃗ (spherical potentials) • Integrals constrain geometry of orbits. • Constant of motion: a function C(⃗x,⃗v, t) which is constant along any orbit: examples: C(⃗x(t1),⃗v(t1),t1)=C(⃗x(t2),⃗v(t2),t2) • 1. Spherical potentials: E,L ,L ,L are integrals of motion, but also E,|L| C is a function of ⃗x, ⃗v, and time t. x y z and the direction of L⃗ (given by the unit vector ⃗n, Integral of motion which is defined by two independent numbers). ⃗n de- • : a function I(x, v) which is fines the plane in which ⃗x and ⃗v must lie. Define coor- constant along any orbit: dinate system with z axis along ⃗n I[⃗x(t1),⃗v(t1)] = I[⃗x(t2),⃗v(t2)] ⃗x =(x1,x2, 0) I is not a function of time ! Thus: integrals of motion are constants of motion, ⃗v =(v1,v2, 0) but constants of motion are not always integrals of motion! → ⃗x and ⃗v constrained to 4D region of the 6D phase space. -

STUDENT HIGHLIGHT – Hassan Najafi Alishah - “Symplectic Geometry, Poisson Geometry and KAM Theory” (Mathematics)

SEPTEMBER OCTOBER // 2010 NUMBER// 28 STUDENT HIGHLIGHT – Hassan Najafi Alishah - “Symplectic Geometry, Poisson Geometry and KAM theory” (Mathematics) Hassan Najafi Alishah, a CoLab program student specializing in math- The Hamiltonian function (or energy function) is constant along the ematics, is doing advanced work in the Mathematics Departments of flow. In other words, the Hamiltonian function is a constant of motion, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, and the University of Texas at Austin. a principle that is sometimes called the energy conservation law. A This article provides an overview of his research topics. harmonic spring, a pendulum, and a one-dimensional compressible fluid provide examples of Hamiltonian Symplectic and Poisson geometries underlie all me- systems. In the former, the phase spaces are symplec- chanical systems including the solar system, the motion tic manifolds, but for the later phase space one needs of a rigid body, or the interaction of small molecules. the more general concept of a Poisson manifold. The origins of symplectic and Poisson structures go back to the works of the French mathematicians Joseph-Louis A Hamiltonian system with enough suitable constants Lagrange (1736-1813) and Simeon Denis Poisson (1781- of motion can be integrated explicitly and its orbits can 1840). Hermann Weyl (1885-1955) first used “symplectic” be described in detail. These are called completely in- with its modern mathematical meaning in his famous tegrable Hamiltonian systems. Under appropriate as- monograph “The Classical groups.” (The word “sym- sumptions (e.g., in a compact symplectic manifold) plectic” itself is derived from a Greek word that means the motions of a completely integrable Hamiltonian complex.) Lagrange introduced the concept of a system are quasi-periodic. -

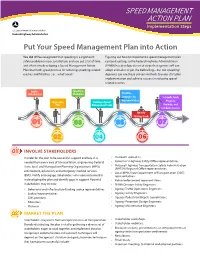

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps Put Your Speed Management Plan into Action You did it! You recognized that speeding is a significant Figuring out how to implement a speed management plan safety problem in your jurisdiction, and you put a lot of time can be daunting, so the Federal Highway Administration and effort into developing a Speed Management Action (FHWA) has developed a set of steps that agency staff can Plan that holds great promise for reducing speeding-related adopt and tailor to get the ball rolling—but not speeding! crashes and fatalities. So…what’s next? Agencies can use these proven methods to jump start plan implementation and achieve success in reducing speed- related crashes. Involve Identify a Stakeholders Champion Prioritize Strategies for Set Goals, Track Implementation Market the Develop a Speed Progress, Plan Management Team Evaluate, and Celebrate Success Identify Strategy Leads INVOLVE STAKEHOLDERS In order for the plan to be successful, support and buy-in is • Outreach specialists. needed from every area of transportation: engineering (Federal, • Governor’s Highway Safety Office representatives. State, local, and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO), • National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) Regional Office representatives. enforcement, education, and emergency medical services • Local/MPO/State Department of Transportation (DOT) (EMS). Notify and engage stakeholders who were instrumental representatives. in developing the plan and identify gaps in support. Potential • Police/enforcement representatives. stakeholders may include: • FHWA Division Safety Engineers. • Behavioral and infrastructure funding source representatives. • Agency Traffic Operations Engineers. • Judicial representatives. • Agency Safety Engineers. • EMS providers. • Agency Pedestrian/Bicycle Coordinators. • Educators. • Agency Pavement Design Engineers.