Short History of Brazilian Aeronautics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS – 204 Charles Lewis Aviation Collection

MS – 204 Charles Lewis Aviation Collection Wright State University Special Collections and Archives Container Listing Sub-collection A: Airplanes Series 1: Evolution of the Airplane Box File Description 1 1 Evolution of Aeroplane I 2 Evolution of Aeroplane II 3 Evolution of Aeroplane III 4 Evolution of Aeroplane IV 5 Evolution of Aeroplane V 6 Evolution of Aeroplane VI 7 Evolution of Aeroplane VII 8 Missing Series 2: Pre-1914 Airplanes Sub-series 1: Drawings 9 Aeroplanes 10 The Aerial Postman – Auckland, New Zealand 11 Aeroplane and Storm 12 Airliner of the Future Sub-series 2: Planes and Pilots 13 Wright Aeroplane at LeMans 14 Wright Aeroplane at Rheims 15 Wilbur Wright at the Controls 16 Wright Aeroplane in Flight 17 Missing 18 Farman Airplane 19 Farman Airplane 20 Antoinette Aeroplane 21 Bleriot and His Monoplane 22 Bleriot Crossing the Channel 23 Bleriot Airplane 24 Cody, Deperdussin, and Hanriot Planes 25 Valentine’s Aeroplane 26 Missing 27 Valentine and His Aeroplane 28 Valentine and His Aeroplane 29 Caudron Biplane 30 BE Biplane 31 Latham Monoplane at Sangette Series 3: World War I Sub-series 1: Aerial Combat (Drawings) Box File Description 1 31a Moraine-Saulnier 31b 94th Aero Squadron – Nieuport 28 – 2nd Lt. Alan F. Winslow 31c Fraser Pigeon 31d Nieuports – Various Models – Probably at Issoudoun, France – Training 31e 94th Aero Squadron – Nieuport – Lt. Douglas Campbell 31f Nieuport 27 - Servicing 31g Nieuport 17 After Hit by Anti-Aircraft 31h 95th Aero Squadron – Nieuport 28 – Raoul Lufbery 32 Duel in the Air 33 Allied Aircraft -

Five by Five a M Essage F Rom the P Resident

Vol. 1, No. 2 Summer 2021 The Newsletter of the Helicopter Conservancy, Ltd. FIVE BY FIVE A M ESSAGE F ROM THE P RESIDENT ne of my earliest memories is of a was able to intervene. So my own rescuer family trip to the beach. I remember ultimately saved not just one life that day O the warmth of the sand between my back in 1969 but two. toes, the blue sky overhead and the roar of the surf as it broke on the Pacific coast. The Helicopters are well known for their im- year was 1969. I was oblivious to the war in portant role in rescue work, a role that dates Southeast Asia then in full swing; I knew back to the early machines of the 1940s. With INSIDE THIS ISSUE: nothing of the tumultuous events here at their ability to get in and out of tight spots, home. In fact, I was just old enough to walk helicopters are ideally suited for this task. Five by Five 1 and, using this newfound ability, slipped away Around the Hangar 2 from my parents to go explore this exciting Their crews are equally at home in this mis- and unfamiliar place. sion and have earned a reputation for re- Firestorm 3 maining cool under pressure, often facing I toddled over to get a better look at the extraordinary personal risk to deliver their 6 The Last Dragon waves and a school of small fish I had spotted charges—all in a day’s work. Short Final 8 swimming in the shallows. -

Análise Das Implicações Do Monopólio Do Transporte Aéreo No Brasil

ANÁLISE DAS IMPLICAÇÕES DO MONOPÓLIO DO TRANSPORTE AÉREO NO BRASIL. Analysis of the implications of the air transport monopoly in Brazil. Wilson Alves dos Santos Junior1 RESUMO O transporte aéreo, como qualquer outra atividade humana, também representa uma forma de produção e acumulação de riqueza por parte de uma pequena parcela da sociedade capitalista. Desde a sua invenção no início do século XX, o avião é o único meio de transporte capaz de percorrer longas distâncias em pouco tempo, com maior segurança e confiabilidade, podendo atingir qualquer ponto do planeta em questões de horas. Contudo, mesmo com todas essas características, a aviação não está à disposição de qualquer pessoa. A indústria do transporte aéreo, nos países capitalistas possuem interesses contraditórios, onde as companhias privadas exploram esse importante setor para a sociedade com base apenas na necessidade de obtenção do lucro. Analisar as implicações das contradições do transporte aéreo como criador de valor apropriado pelos capitalistas ou como bem comum para os membros da sociedade é um desafio que deve buscar soluções na superação do modo de produção capitalista. Este artigo propõe debater algumas características necessárias para um novo tipo de transporte aéreo baseado nos interesses sociais. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Transporte Aéreo, Rede Aérea, Monopólio. ABSTRACT Air transport, like any other human activity, also represents a form of production and accumulation of wealth by a small portion of capitalist society. Since its invention in the early twentieth century, the plane is the only means of transport capable of traveling long distances in a short time, with greater safety and reliability, and can reach any point on the planet in hours. -

1908-1909 : La Véritable Naissance De L'aviation

1908-1909 : LA VÉRITABLE 05 Histoire et culture NAISSANCE DE L’AVIATION. de l’aéronautique et du spatial A) Les démonstrations en France de Farman et des frères Wright. A la veille de 1908, ballons et dirigeables dominent encore le ciel, malgré les succès prometteurs des frères Wright, de Santos Dumont et de Vuia. A Issy-les-Moulineaux, le 13 janvier 1908, Farman réussit officiellement le premier vol contrôlé en circuit fermé d’un kilomètre à bord d’un Voisin et remporte les 50 000 francs promis par Archdeacon et Deutsch de la Meurthe. Farman effectue ensuite le premier vol de ville à ville, entre Bouy et Reims, soit 27 km. En tournée aux Etats-Unis, il invente le mot “aileron” : il baptise ainsi les volets en bout d'aile d'avions qui sont présentés. Le premier passager de l'histoire de l'aviation serait Ernest Archdeacon qui embarque avec Henri Farman à Gand (Belgique). En août 1908, les frères Wright s’installent en France pour vendre leur « Flyer » sous licence. Le 31 décembre, Wilbur remporte les 20 000 francs du prix Michelin pour avoir effectué le plus long vol de l’année au camp d’Auvours : 124,7 km en 2h20. Les Wright voulaient garder secret leur système de gauchissement des ailes (torsion du bout des ailes pour incliner de côté un avion) au point de dormir à côté de l’avion. Les Américains fondent la première école de pilotage au monde à Pau. Aux Etats-Unis, le Wright Flyer III, piloté par Orville Wright, est victime d'un accident à la suite de la rupture d'une des hélices en plein vol. -

Flânerie Au Cœur Du Quartier Coteaux/Bords De Seine

Flânerie au cœur du quartier COTEAUX/BORDS DE SEINE 2km 1h30 www.saintcloud.fr Flânerie au cœur du quartier COTEAUX/BORDS DE SEINE Fière de son histoire et de son patrimoine, seuses au XIXe siècle. Le quai Carnot était la municipalité de Saint-Cloud vous invite également investi d’hôtels et restaurants à flâner dans les rues de la commune en qui accueillaient les Parisiens venus profi- publiant cinq livrets qui vous feront décou- ter des distractions organisées dans le parc vrir le patrimoine historique, artistique et de Saint-Cloud. Ce quartier devient plus architectural des différents quartiers de résidentiel au début du XXe siècle lorsque la Saint-Cloud. Le passionné de patrimoine Société foncière des Coteaux et du bois de ou l’amateur de belles promenades pourra Boulogne acquiert les terrains situés entre cheminer, de manière autonome, à l’aide les deux voies de chemin de fer. de ce dépliant, en suivant les points numé- rotés sur le plan (au verso) qui indique les Parcours de 2 kilomètres lieux emblématiques de la ville. Durée : environ 1h30 Partez à la découverte des vestiges, des En savoir plus sites classés ou remarquables qui vous Musée des Avelines, musée d’art révèleront la richesse de Saint-Cloud. Son et d’histoire de Saint-Cloud histoire commence il y a plus de 2000 ans 60, rue Gounod lorsque la ville n’était encore qu’une simple 92210 Saint-Cloud PARUTION JUILLET 2017 bourgade gallo-romaine appelée Novigen- 01 46 02 67 18 www.musee-saintcloud.fr tum. Entrée libre Le quartier des Coteaux, autrefois agricole, du mercredi au samedi de 12h à 18h vivait de la culture de la vigne tandis que Dimanche de 14h à 18h les bords de Seine étaient plutôt réservés Le musée organise des visites guidées à l’activité des pêcheurs puis des blanchis- de la ville. -

1914/1918 : Nos Anciens Et Le Développement De L' Aviation

1914/1918 : Nos Anciens et le Développement de l’aviation militaire René Couillandre, Jean-Louis Eytier, Philippe Jung 06 novembre 2018 - 18h00 Talence 1914/1918 : Nos Anciens et le développement de l’ aviation militaire Chers Alumnis, chers Amis, Merci d’être venus nombreux participer au devoir de mémoire que toute Amicale doit à ses diplômés. Comme toute la société française en 1914, les GADZARTS, à l’histoire déjà prestigieuse, et SUPAERO, née en 1909, ont été frappés par le 1er conflit mondial. Les jeunes diplômés, comme bien d’autres ont été mobilisés pour répondre aux exigences nationales. Le conflit que tous croyaient de courte durée s’est révélé dévoreur d’hommes : toute intelligence, toute énergie, toute compétence fut mise au service de la guerre. L’aviation naissante, forte de ses avancées spectaculaires s’est d’abord révélé un service utile aux armes. Elle a rapidement évolué au point de devenir indispensable sur le champ de bataille et bien au-delà, puis de s’imposer comme une composante essentielle du conflit. Aujourd’hui, au centenaire de ce meurtrier conflit, nous souhaitons rendre hommage à nos Anciens qui, avec tant d’autres, de façon anonyme ou avec éclat ont permis l’évolution exceptionnelle de l’aviation militaire. Rendre hommage à chacun est impossible ; les célébrer collectivement, reconnaître leurs sacrifices et leurs mérites c’est nourrir les racines de notre aéronautique moderne. Nous vous proposons pour cela, après un rappel sur l’ aviation en 1913, d’effectuer un premier parcours sur le destin tragique de quelques camarades morts au champ d’honneur ou en service aérien en les resituant dans leur environnement aéronautique ; puis lors d’un second parcours, de considérer la présence et l’apport d’autres diplômés à l’évolution scientifique, technique, industrielle ou opérationnelle de l’ aviation au cours de ces 4 années. -

CHAMPION AEROSPACE LLC AVIATION CATALOG AV-14 Spark

® CHAMPION AEROSPACE LLC AVIATION CATALOG AV-14 REVISED AUGUST 2014 Spark Plugs Oil Filters Slick by Champion Exciters Leads Igniters ® Table of Contents SECTION PAGE Spark Plugs ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Product Features ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Spark Plug Type Designation System ............................................................................................................. 2 Spark Plug Types and Specifications ............................................................................................................. 3 Spark Plug by Popular Aircraft and Engines ................................................................................................ 4-12 Spark Plug Application by Engine Manufacturer .........................................................................................13-16 Other U. S. Aircraft and Piston Engines ....................................................................................................17-18 U. S. Helicopter and Piston Engines ........................................................................................................18-19 International Aircraft Using U. S. Piston Engines ........................................................................................ 19-22 Slick by Champion ............................................................................................................................. -

Historia De La Aviación Comercial Desde 1909 Hasta Nuestros Días

FACULTAT DE FILOSOFIA I LETRES, DEPARTAMENT DE CIÈNCIES HISTÒRIQUES I TEORIA DE LES ARTS HISTORIA DE LA AVIACIÓN COMERCIAL DESDE 1909 HASTA NUESTROS DÍAS TESIS DOCTORAL PRESENTADA POR EL DR. MARTÍN BINTANED ARA DIRIGIDA POR EL DR. SEBASTIÁ SERRA BUSQUETS CATEDRÀTIC D'HISTÒRIA CONTEMPORÀNIA PARA OPTAR AL TÍTULO DE DOCTOR EN HISTORIA CURSO ACADÉMICO 2013/2014 Martín Bintaned Ara 2 Historia de la aviación comercial Resumen Esta tesis doctoral investiga acerca de la aportación de la aviación comercial a la historia contemporánea, en particular por su impacto en las relaciones exteriores de los países, su papel facilitador en la actividad económica internacional y por su contribución al desarrollo del turismo de masas. La base de trabajo ha sido el análisis de la prensa especializada, a partir de la cual se han identificado los casos innovadores. Gracias al análisis de su origen (tecnológico, geo- político, aero-político, corporativo, de producto y en la infraestructura) y a su contextualización, hemos podido trazar la historia de la aviación comercial desde su origen en 1919 hasta nuestros días. Palabras clave: Historia contemporánea, Aviación comercial, Política aérea, Relaciones internacionales, Turismo, Innovación, Aerolíneas, Aeropuertos Abstract This doctoral thesis analyses the contribution of commercial aviation to the contemporary history, particularly in the field of external relations, international economy and mass tourism. We have identified all innovations with a structural impact on the industry through specialised press, considering the changes on technology, geopolitics, aeropolitics, business models, product and services, and infrastructure. This methodology has allowed us to write the history of the commercial aviation since its origin in 1919. -

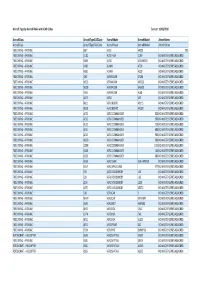

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016 AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AJ27 ACAC ARJ21 700 FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE CUB2 ACES HIGH CUBY NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE SACR ACRO ADVANCED NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A700 ADAM A700 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A500 ADAM A500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE F26T AERMACCHI SF260 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M326 AERMACCHI MB326 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M308 AERMACCHI MB308 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE LA60 AERMACCHI AL60 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AAT3 AERO AT3 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB11 AERO BOERO AB115 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB18 AERO BOERO AB180 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC52 AERO COMMANDER 520 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC50 AERO COMMANDER 500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC72 AERO COMMANDER 720 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC6L AERO COMMANDER 680 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC56 AERO COMMANDER 560 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M200 AERO COMMANDER 200 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE JCOM AERO COMMANDER 1121 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE VO10 AERO COMMANDER 100 NO MASTER -

The Voisin Biplane by Robert G

THE VOISIN BIPLANE BY ROBERT G. WALDVOGEL A single glance at the Voisin Biplane reveals exactly what one would expect of a vintage aircraft: a somewhat ungainly design with dual, fabric-covered wings; a propeller; an aerodynamic surface protruding ahead of its airframe; and a boxy, kite-resembling tail. But, by 1907 standards, it had been considered “advanced.” Its designer, Gabriel Voisin, son of a provincial engineer, was born in Belleville, France, in 1880, initially demonstrating mechanical and aeronautical aptitude through his boat, automobile, and kite interests. An admirer of Clement Ader, he trained as an architect and draftsman at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, and was later introduced to Ernest Archdeacon, a wealthy lawyer and aviation enthusiast, who subsequently commissioned him to design a glider. Using inaccurate and incomplete drawings of the Wright Brothers’ 1902 glider published in L’Aerophile, the Aero-Club’s journal, Voisin constructed an airframe in January of 1904 which only bore a superficial resemblance to its original. Sporting dual wings subdivided by vertical partitions, a forward elevating plane, and a two-cell box-kite tail, it was devoid of the Wright-devised wing- warping method, and therefore had no means by which lateral control could be exerted. Two-thirds the size of the original, it was 40 pounds lighter. Supported by floats and tethered to a Panhard-engined racing boat, the glider attempted its first fight from the Seine River on June 8, 1905, as described by Voisin himself. “Gradually and cautiously, (the helmsman) took up the slack of my towing cable…” he had written. -

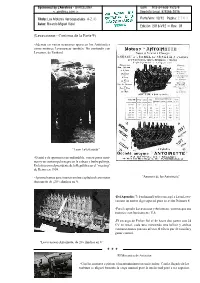

Levavasseur.- Continua De La Parte 9

Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © Parte/Vers: 10/12 Página: 2701 Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal Edición 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 (Levavasseur.- Continua de la Parte 9) -Además en varias ocasiones aparecen los Antoinettes como motores Levavasseur también. No confundir con Levassor, de Panhard. “Leon Levavasseur” -Genial y de apariencia inconfundible, con su gorra mari- nera y un curioso pelo negro en la cabeza y barba peliroja. En la foto con el presidente de la República en el “meeting” de Reims en 1909. -Aprovechamos para insertar en éste capítulo el raro motor “Anuncio de los Antoinette” Antoinette de ¡20! cilindros en V. -Del Apendice 7: Ferdinand Ferber encargó a Leon Leva- vasseur un motor algo especial para su avión Número 8. -Por el capitulo Levavasseur y Antoinette, vemnos que sus motores eran basicamente V-8. -El encargo de Ferber fué el de hacer dos partes con 24 CV en total, cada una moviendo una hélice y ambas contrarotatorias para no afectar el efecto par de torsión y ganar control. “Levavasseur-Antoinette, de 20 cilindros en V” * * * El Mecanico de Aviación -Con los motores a piston, el mantenimiento era más arduo. Con la llegada de las turbinas se aligeró bastante la carga manual pero la intelectual pasó a ser superior. Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 Este facsímil es < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 ORIGINAL si la Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © página anterior tiene Parte/Vers: 10/12 Página: 2702 el sello con tinta Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal VERDE Edición: 2018-V12 = Rev. -

A Century of Wind Tunnels Since Eiffel Bruno Chanetz

A century of wind tunnels since Eiffel Bruno Chanetz To cite this version: Bruno Chanetz. A century of wind tunnels since Eiffel. Comptes Rendus Mécanique, Elsevier Masson, 2017, 345 (8), pp.581-594. 10.1016/j.crme.2017.05.012. hal-01570740 HAL Id: hal-01570740 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01570740 Submitted on 31 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. C. R. Mecanique 345 (2017) 581–594 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Mecanique www.sciencedirect.com A century of fluid mechanics: 1870–1970 / Un siècle de mécanique des fluides : 1870–1970 A century of wind tunnels since Eiffel Bruno Chanetz ONERA, Chemin de la Hunière, BP 80100, 91123 Palaiseau cedex, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Fly higher, faster, preserve the life of test pilots and passengers, many challenges faced by Received 15 November 2016 man since the dawn of the twentieth century, with aviation pioneers. Contemporary of the Accepted 8 March 2017 first aerial exploits, wind tunnels, artificially recreating conditions encountered during the Available online 13 July 2017 flight, have powerfully contributed to the progress of aeronautics.