Mantle Cell Lymphoma and Its Management: Where Are We Now? Abdullah Ladha1, Jianzhi Zhao2, Elliot M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application of a Characterized Pre-Clinical

THE APPLICATION OF A CHARACTERIZED PRE-CLINICAL GLIOBLASTOMA ONCOSPHERE MODEL TO IN VITRO AND IN VIVO THERAPEUTIC TESTING by Kelli M. Wilson A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March, 2014 ABSTRACT Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is a lethal brain cancer with a median survival time (MST) of approximately 15 months following treatment. A serious challenge facing the development of new drugs for the treatment of GBM is that preclinical models fail to replicate the human GBM phenotype. Here we report the Johns Hopkins Oncosphere Panel (JHOP), a panel of GBM oncosphere cell lines. These cell lines were validated by their ability to form tumors intracranially with histological features of human GBM and GBM variant tumors. We then completed whole exome sequencing on JHOP and found that they contain genetic alterations in GBM driver genes such as PTEN, TP53 and CDKN2A. Two JHOP cell lines were utilized in a high throughput drug screen of 466 compounds that were selected to represent late stage clinical development and a wide range of mechanisms. Drugs that were inhibitory in both cell lines were EGFR inhibitors, NF-kB inhibitors and apoptosis activators. We also examined drugs that were inhibitory in a single cell line. Effective drugs in the PTEN null and NF1 wild type cell line showed a limited number of drug targets with EGFR inhibitors being the largest group of cytotoxic compounds. However, in the PTEN mutant, NF1 null cell line, VEGFR/PDGFR inhibitors and dual PIK3/mTOR inhibitors were the most common effective compounds. -

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Confidential Clinical study protocol number: J1228 Page 1 Version Date: May 7, 2018 IRB study Number: NA_00067315 A Trial of maintenance Rituximab with mTor inhibition after High-dose Consolidative Therapy in CD20+, B-cell Lymphomas, Gray Zone Lymphoma, and Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Principal Investigator: Douglas E. Gladstone, MD The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins 1650 Orleans Street, CRBI-287 Baltimore, MD 21287 Phone: 410-955-8781 Fax: 410-614-1005 Email: [email protected] IRB Protocol Number: NA_00067315 Study Number: J1228 IND Number: EXEMPT Novartis Protocol Number: CRAD001NUS157T Version: May 7, 2018 Co-Investigators: Jonathan Powell 1650 Orleans Street, CRBI-443 Phone: 410-502-7887 Fax: 443-287-4653 Email: [email protected] Richard Jones 1650 Orleans Street, CRBI-244 Phone: 410-955-2006 Fax: 410-614-7279 Email: [email protected] Confidential Clinical study protocol number: J1228 Page 2 Version Date: May 7, 2018 IRB study Number: NA_00067315 Satish Shanbhag Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center 301 Building, Suite 4500 4940 Eastern Ave Phone: 410-550-4061 Fax: 410-550-5445 Email: [email protected] Statisticians: Gary Rosner Phone: 410-955-4884 Email: [email protected] Marianna Zahurak Phone: 410-955-4219 Email: [email protected] Confidential Clinical study protocol number: J1228 Page 3 Version Date: May 7, 2018 IRB study Number: NA_00067315 Table of contents Table of contents ......................................................................................................................... 3 List of abbreviations -

LEUSTATIN (Cladribine) Injection Should Be Administered Under the Supervision of a Qualified Physician Experienced in the Use of Antineoplastic Therapy

LEUSTATIN (cladribine) Injection For Intravenous Infusion Only WARNING LEUSTATIN (cladribine) Injection should be administered under the supervision of a qualified physician experienced in the use of antineoplastic therapy. Suppression of bone marrow function should be anticipated. This is usually reversible and appears to be dose dependent. Serious neurological toxicity (including irreversible paraparesis and quadraparesis) has been reported in patients who received LEUSTATIN Injection by continuous infusion at high doses (4 to 9 times the recommended dose for Hairy Cell Leukemia). Neurologic toxicity appears to demonstrate a dose relationship; however, severe neurological toxicity has been reported rarely following treatment with standard cladribine dosing regimens. Acute nephrotoxicity has been observed with high doses of LEUSTATIN (4 to 9 times the recommended dose for Hairy Cell Leukemia), especially when given concomitantly with other nephrotoxic agents/therapies. DESCRIPTION LEUSTATIN (cladribine) Injection (also commonly known as 2-chloro-2΄-deoxy- β -D-adenosine) is a synthetic antineoplastic agent for continuous intravenous infusion. It is a clear, colorless, sterile, preservative-free, isotonic solution. LEUSTATIN Injection is available in single-use vials containing 10 mg (1 mg/mL) of cladribine, a chlorinated purine nucleoside analog. Each milliliter of LEUSTATIN Injection contains 1 mg of the active ingredient and 9 mg (0.15 mEq) of sodium chloride as an inactive ingredient. The solution has a pH range of 5.5 to 8.0. Phosphoric -

Synthesis of Ribavirin, Tecadenoson, and Cladribine by Enzymatic Transglycosylation

catalysts Article Synthesis of Ribavirin, Tecadenoson, and Cladribine by Enzymatic Transglycosylation 1, 2 2,3 2 Marco Rabuffetti y, Teodora Bavaro , Riccardo Semproli , Giulia Cattaneo , Michela Massone 1, Carlo F. Morelli 1 , Giovanna Speranza 1,* and Daniela Ubiali 2,* 1 Department of Chemistry, University of Milan, via Golgi 19, I-20133 Milano, Italy; marco.rabuff[email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (C.F.M.) 2 Department of Drug Sciences, University of Pavia, viale Taramelli 12, I-27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (T.B.); [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (G.C.) 3 Consorzio Italbiotec, via Fantoli 15/16, c/o Polo Multimedica, I-20138 Milano, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (D.U.); Tel.: +39-02-50314097 (G.S.); +39-0382-987889 (D.U.) Present address: Department of Food, Environmental and Nutritional Sciences, University of Milan, y via Mangiagalli 25, I-20133 Milano, Italy. Received: 7 March 2019; Accepted: 8 April 2019; Published: 12 April 2019 Abstract: Despite the impressive progress in nucleoside chemistry to date, the synthesis of nucleoside analogues is still a challenge. Chemoenzymatic synthesis has been proven to overcome most of the constraints of conventional nucleoside chemistry. A purine nucleoside phosphorylase from Aeromonas hydrophila (AhPNP) has been used herein to catalyze the synthesis of Ribavirin, Tecadenoson, and Cladribine, by a “one-pot, one-enzyme” transglycosylation, which is the transfer of the carbohydrate moiety from a nucleoside donor to a heterocyclic base. As the sugar donor, 7-methylguanosine iodide and its 20-deoxy counterpart were synthesized and incubated either with the “purine-like” base or the modified purine of the three selected APIs. -

COMPARISON of the WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & Ephmra/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION

COMPARISON OF THE WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION: VERSION June 2019 2 Comparison of the WHO ATC Classification and EphMRA / Intellus Worldwide Anatomical Classification The following booklet is designed to improve the understanding of the two classification systems. The development of the two systems had previously taken place separately. EphMRA and WHO are now working together to ensure that there is a convergence of the 2 systems rather than a divergence. In order to better understand the two classification systems, we should pay attention to the way in which substances/products are classified. WHO mainly classifies substances according to the therapeutic or pharmaceutical aspects and in one class only (particular formulations or strengths can be given separate codes, e.g. clonidine in C02A as antihypertensive agent, N02C as anti-migraine product and S01E as ophthalmic product). EphMRA classifies products, mainly according to their indications and use. Therefore, it is possible to find the same compound in several classes, depending on the product, e.g., NAPROXEN tablets can be classified in M1A (antirheumatic), N2B (analgesic) and G2C if indicated for gynaecological conditions only. The purposes of classification are also different: The main purpose of the WHO classification is for international drug utilisation research and for adverse drug reaction monitoring. This classification is recommended by the WHO for use in international drug utilisation research. The EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide classification has a primary objective to satisfy the marketing needs of the pharmaceutical companies. Therefore, a direct comparison is sometimes difficult due to the different nature and purpose of the two systems. -

Recent Topics on the Mechanisms of Immunosuppressive Therapy-Related Neurotoxicities

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 May 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201905.0358.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3210; doi:10.3390/ijms20133210 1 of 39 1 Review 2 Recent topics on the mechanisms of 3 immunosuppressive therapy-related neurotoxicities 4 Wei Zhang 1, Nobuaki Egashira 1,2,* and Satohiro Masuda 1,2 5 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 6 Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan 7 2 Department of Pharmacy, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan 8 * Correspondence: [email protected], Tel.: 81-92-642-5920 9 Abstract: Although transplantation procedures have been developed for patients with end-stagec 10 hepatic insufficiency or other diseases, allograft rejection still threatens patient health and lifespan. 11 Over the last few decades, the emergence of immunosuppressive agents, such as calcineurin 12 inhibitors (CNIs) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, have strikingly 13 increased graft survival. Unfortunately, immunosuppressive agent-related neurotoxicity is 14 commonly occurred in clinical situations, with the majority of neurotoxicity cases caused by CNIs. 15 The possible mechanisms whereby CNIs cause neurotoxicity include: increasing the permeability 16 or injury of the blood-brain barrier, alterations of mitochondrial function, and alterations in 17 electrophysiological state. Other immunosuppressants can also induce neuropsychiatric 18 complications. For example, mTOR inhibitors induce seizures; mycophenolate mofetil induces 19 depression and headache; methotrexate affects the central nervous system; mouse monoclonal 20 immunoglobulin G2 antibody against cluster of differentiation 3 also induces headache; and 21 patients using corticosteroids usually experience cognitive alteration. -

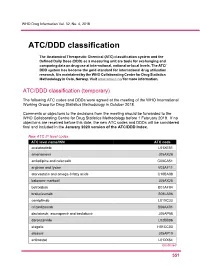

ATC/DDD Classification

WHO Drug Information Vol. 32, No. 4, 2018 ATC/DDD classification The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system and the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) as a measuring unit are tools for exchanging and comparing data on drug use at international, national or local levels. The ATC/ DDD system has become the gold standard for international drug utilization research. It is maintained by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology in Oslo, Norway. Visit www.whocc.no/ for more information. ATC/DDD classification (temporary) The following ATC codes and DDDs were agreed at the meeting of the WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology in October 2018. Comments or objections to the decisions from the meeting should be forwarded to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology before 1 February 2019. If no objections are received before this date, the new ATC codes and DDDs will be considered final and included in the January 2020 version of the ATC/DDD Index. New ATC 5th level codes ATC level name/INN ATC code acalabrutinib L01XE51 amenamevir J05AX26 amlodipine and celecoxib C08CA51 arginine and lysine V03AF11 atorvastatin and omega-3 fatty acids C10BA08 baloxavir marboxil J05AX25 betrixaban B01AF04 brolucizumab S01LA06 cemiplimab L01XC33 crizanlizumab B06AX01 daclatasvir, asunaprevir and beclabuvir J05AP58 darolutamide L02BB06 elagolix H01CC03 elbasvir J05AP10 entinostat L01XX64 Continued 5 51 ATC/DDD classification WHO Drug Information Vol. 32, No. 4, 2018 New ATC 5th level codes (continued) -

Cladribine Injection

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrCLADRIBINE INJECTION Solution for Intravenous Injection 1 mg/mL USP Antineoplastic / Chemotherapeutic Agent Fresenius Kabi Canada Ltd. Date of Revision: 165 Galaxy Blvd, Suite 100 June 9, 2015 Toronto, ON M9W 0C8 Control No.: 181078 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION ......................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ............................................................................... 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ..................................................................................... 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS .......................................................................................................... 3 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ......................................................................................... 4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ........................................................................................................... 7 DRUG INTERACTIONS ......................................................................................................... 10 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ..................................................................................... 11 OVERDOSAGE ....................................................................................................................... 13 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ................................................................... 14 STORAGE AND STABILITY ................................................................................................ -

Original Article Treatment of Hairy Cell Leukemia with Cladribine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Annals of Oncology 13: 1641–1649, 2002 Original article DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdf272 Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine) by subcutaneous bolus injection: a phase II study A. von Rohr1*, S.-F. H. Schmitz2, A. Tichelli3, U. Hess4, D. Piguet5, M. Wernli6, N. Frickhofen7, G. Konwalinka8, G. Zulian9, M. Ghielmini10, B. Rufener2, C. Racine1, M. F. Fey1, T. Cerny1, D. Betticher1 & A. Tobler11 On Behalf of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), Bern, Switzerland 1Institute of Medical Oncology, Inselspital, Bern; 2SIAK Coordinating Center, Bern; 3Division of Hematology, Kantonsspital, Basel; 4Department of Internal Medicine, Kantonsspital, St Gallen; 5Department of Internal Medicine, Hôpital des Cadolles, Neuchâtel; 6Department of Internal Medicine, Kantonsspital, Aarau, Switzerland; 7Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Ulm, Germany; 8Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Innsbruck, Austria; 9Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Geneva; 10Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Bellinzona; 11Central Hematology Laboratory, University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland Received 8 January 2002; revised 11 April 2002; accepted 24 April 2002 Background: To assess the activity and toxicity of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine, CDA) given by subcutaneous bolus injections to patients with hairy cell leukemia (HCL). Patients and methods: Sixty-two eligible patients with classic or prolymphocytic HCL (33 non- pretreated patients, 15 patients with relapse after previous treatment, and 14 patients with progressive disease during a treatment other than CDA) were treated with CDA 0.14 mg/kg/day by subcutaneous bolus injections for five consecutive days. -

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors and Clinical Outcomes in Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients

Article Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors and Clinical Outcomes in Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients | Sunil V. Badve,*†‡ Elaine M. Pascoe,* Michael Burke,§ Philip A. Clayton, ¶ Scott B. Campbell,§ Carmel M. Hawley,*§ | Wai H. Lim,** Stephen P. McDonald, ¶ Germaine Wong,†† and David W. Johnson*§ Abstract Background and objectives Emerging evidence from recently published observational studies and an individual – *Australasian Kidney patient data meta analysis shows that mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor use in kidney transplantation Trials Network, School is associated with increased mortality. Therefore, all-cause mortality and allograft loss were compared of Medicine, between use and nonuse of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in patients from Australia and New University of Zealand, where mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor use has been greater because of heightened skin Queensland, cancer risk. Brisbane, Australia; †Department of Nephrology, Design, setting, participants, & measurements Our longitudinal cohort study included 9353 adult patients who St. George Hospital, underwent 9558 kidney transplants between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2012 and had allograft survival Sydney, Australia; ‡ $1 year. Risk factors for all-cause death and all–cause and death–censored allograft loss were analyzed by Renal and Metabolic Division, The George multivariable Cox regression using mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor as a time-varying covariate. fi Institute for Global Additional analyses evaluated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor use at xed time points of baseline and Health, Sydney, 1year. Australia; §Department of Results Patients using mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors were more likely to be white and have a history Nephrology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, of pretransplant cancer. Over a median follow-up of 7 years, 1416 (15%) patients died, and 2268 (24%) allografts Brisbane, Australia; | were lost. -

Targeting Mtor Signaling Overcomes Acquired Resistance to Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition in BRAF-Mutant Melanoma

www.nature.com/onc Oncogene ARTICLE OPEN Targeting mTOR signaling overcomes acquired resistance to combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutant melanoma Beike Wang1,11, Wei Zhang1,11, Gao Zhang 2,10,11, Lawrence Kwong3, Hezhe Lu4, Jiufeng Tan2, Norah Sadek2, Min Xiao2, Jie Zhang 5, 6 2 2 2 2 5 7 6 Marilyne Labrie , Sergio Randell , Aurelie Beroard , Eric Sugarman✉ , Vito W. Rebecca✉ , Zhi Wei , Yiling Lu , Gordon B. Mills , Jeffrey Field8, Jessie Villanueva2, Xiaowei Xu9, Meenhard Herlyn 2 and Wei Guo 1 © The Author(s) 2021 Targeting MAPK pathway using a combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors is an efficient strategy to treat melanoma harboring BRAF-mutation. The development of acquired resistance is inevitable due to the signaling pathway rewiring. Combining western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and reverse phase protein array (RPPA), we aim to understanding the role of the mTORC1 signaling pathway, a center node of intracellular signaling network, in mediating drug resistance of BRAF-mutant melanoma to the combination of BRAF inhibitor (BRAFi) and MEK inhibitor (MEKi) therapy. The mTORC1 signaling pathway is initially suppressed by BRAFi and MEKi combination in melanoma but rebounds overtime after tumors acquire resistance to the combination therapy (CR) as assayed in cultured cells and PDX models. In vitro experiments showed that a subset of CR melanoma cells was sensitive to mTORC1 inhibition. The mTOR inhibitors, rapamycin and NVP-BEZ235, induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CR cell lines. As a proof-of-principle, we demonstrated that rapamycin and NVP-BEZ235 treatment reduced tumor growth in CR xenograft models. Mechanistically, AKT or ERK contributes to the activation of mTORC1 in CR cells, depending on PTEN status of these cells. -

Cladribine (Leustatin®) Pronounced: “KLAD-Rih-BEAN”

Cladribine Chemotherapy: Cladribine (Leustatin®) Pronounced: “KLAD-rih-BEAN” How drug is given: By vein (IV) Purpose: To treat hairy cell leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and other cancers Things that may occur during or within hours of treatment • Facial flushing (warmth or redness of the face), itching, or a skin rash could occur. These symptoms are due to an allergic response and should be reported to your cancer care team right away. Things that may occur days to weeks after drug is given • Your blood cell counts may drop. This is known as bone marrow suppression. This includes a decrease in your: o Red blood cells, which carry oxygen in your body to help give you energy o White blood cells, which fight infection in your body o Platelets, which help clot the blood to stop bleeding This may happen 7 to 14 days after the drug is given and then blood counts should return to normal. If you have a fever of 100.5°F (38°C) or higher, chills, a cough, or any bleeding problems, tell your cancer care team right away. • Some patients may feel very tired, also known as fatigue. You may need to rest or take naps more often. Mild to moderate exercise can also be helpful in maintaining your energy. • Some patients may have mild nausea. You may be given medicine to help with this. • You may get a headache. Please talk to your doctor or nurse about what you can take for this. • In rare cases, nerves can be affected by this medicine.