Ceramic Oil Lamps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11

Roman Lamps Amy Nicholas, ‘11 The University of Richmond’s Ancient World Gallery contains six ancient Roman lamps. One was donated to the Richmond College Museum in 1885 by Colonel J. L. M. Curry, Confederate soldier and congressman, U.S. Minister to Spain, Trustee of Richmond College, and an ardent collector. Another was donated to the Ancient World Gallery in 1980 from the estate of Mae Keller, the first dean of Westhampton College. In 2008, Gertrude Howland donated a Late Roman lamp which she had acquired while traveling in Jordan in 1963. The others probably come from the original collection of the Richmond College Museum, but their donors are unknown. From various time periods and locations, these objects have come together to form a small, but diverse collection of ancient Roman lamps that exemplify a variety of shapes, sizes, and decorations. Oil lamps, some of the most common household items of the ancient world, were used as early as the Stone Age. Usually made of stone or clay, they were the main source of light in ancient times. Indoors, they provided general lighting throughout the household and also in workshops and enterprises. Lamps were also used outdoors at games or religious festivals and have even been found in mass quantities along streets and above doors, where they must have provided street lighting. Used in temples, they served as both sanctuary decoration and votive offerings to gods and goddesses. The main sources of lamps in modern collections, however, are from tombs. As early as the 3rd millennium BCE, lamps were placed in tombs along with other pottery and jewelry. -

Abstracts-Booklet-Lamp-Symposium-1

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses XI Ancient terracotta lamps from Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean to Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond. Comparative lychnological studies in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and peripheral areas. An international symposium May 16-17, 2019 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Laurent Chrzanovski Last update: 20/05/2019. Izmir, 2019 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium Logo illustration: An early Byzantine terracotta lamp from Alata in Cilicia; museum of Mersin (B. Gürler, 2004). 1 This symposium is dedicated to Professor Hugo Thoen (Ghent / Deinze) who contributed to Anatolian archaeology with his excavations in Pessinus. 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to the ancient lychnological studies in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the symposium...................................6-12. Program of the international symposium on ancient lamps in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond..........................................................................................................................................12-15. Abstracts……………………………………...................................................................................16-67. Constantin -

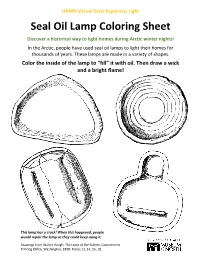

Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Activity

UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamp Coloring Sheet Discover a historical way to light homes during Arctic winter nights! In the Arctic, people have used seal oil lamps to light their homes for thousands of years. These lamps are made in a variety of shapes. Color the inside of the lamp to “fill” it with oil. Then draw a wick and a bright flame! This lamp has a crack! When this happened, people would repair the lamp so they could keep using it. Drawings from Walter Hough, The Lamp of the Eskimo, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1898: Plates 12, 14, 15, 18. UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Light Seal Oil Lamps Seal oil lamps are important in many Arctic cultures, including the Iñupiat, Yup’ik, Inuit, and Unangan (Aleut) peoples. They were essential for survival in the winter, as the lamps provided light, warmed the home, melted water, and even helped cook food. A seal oil lamp could be the most important object in the home! Right: Sophie Nothstine tends a lamp at the 2019 World Eskimo Indian Olympics. Photo from WEIO. Left: Siberian Yup'ik Lamp from St Lawrence Island, UA2001-005- 0019. Right: Lamp from King Salmon, UA2015-016- 0003. Seal oil lamps were usually made of soapstone, a stone that can be carved and is very resistant to heat. They were sometimes made of pottery or other kinds of stone. Seal oil lamps are made in different shapes and designs to help burn the wick and make the best light possible. The lamp was then filled with oil or fat. -

Technology Meets Art: the Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin And

António Cota Fevereiro Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020) Citation: António Cota Fevereiro, “Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.2.2. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Accessed: October 30 2020 Fevereiro: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020) Technology Meets Art: The Wild & Wessel Lamp Factory in Berlin and the Wedgwood Entrepreneurial Model by António Cota Fevereiro Few domestic conveniences in the long nineteenth century experienced such rapid and constant transformation as lights. By the end of the eighteenth century, candles and traditional oil lamps—which had been in use since antiquity—began to be superseded by a new class of oil-burning lamps that, thanks to a series of improvements, provided considerably more light than any previous form of indoor lighting. Plant oils (Europe) or whale oil (United States) fueled these lamps until, by the middle of the nineteenth century, they were gradually replaced by a petroleum derivative called kerosene. Though kerosene lamps remained popular until well into the twentieth century (and in some places until today), by the late nineteenth century they began to be supplanted by gas and electrical lights. -

List of Swiss Cultural Goods: Archaeological Objects

List of Swiss cultural goods: archaeological objects A selection compiled by the Conference of Swiss Canton Archaeologists by order of the Federal Office of Culture FOC Konferenz schweizerischer Kantonsarchäologinnen und Kantonsarchäologen KSKA Conférence Suisse des Archéologues Cantonaux CSAC Conferenza Svizzera degli Archeologi Cantonali CSAC Categories of Swiss cultural goods I. Stone A. Architectural elements: made of granite, sandstone, marble and other types of stone. Capitals, window embrasures, mosaics etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 1500. B. Inscriptions: on various types of stone. Altars, tombstones, honorary inscriptions etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 800. C. Reliefs: on limestone and other types of stone. Stone reliefs, tomb- stone reliefs, decorative elements etc. Approximate date: mainly 50 BC – AD 800. D. Sculptures/statues: made of limestone, marble and other types of stone. Busts, statuettes, burial ornaments etc. Approximate date: mainly 50 BC – AD 800. E. Tools/implements: made of flint and other types of stone. Various tools such as knife and dagger blades, axes and implements for crafts etc. Approximate date: 130 000 BC – AD 800. F. Weapons: made of shale, flint, limestone, sandstone and other types of stone. Arrowheads, armguards, cannonballs etc. Approxi- mate date: 10 000 BC – AD 1500. G. Jewellery/accessories: made of various types of stone. Pendants, beads, finger ring inlays etc. Approximate date: mainly 2800 BC – AD 800. II. Metal A. Statues /statuettes / made of non-ferrous metal, rarely from precious metal. busts: Depictions of animals, humans and deities, portrait busts etc. Approximate date: 50 BC – AD 800. B. Vessels: made of non-ferrous metal, rarely from precious metal and iron. -

Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 1

The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 1 The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder Submission for the Kelsey Experience Jackier Prize Cameron Barnes Student ID: 20155739 AAPTIS 277: The Land of Israel/Palestine Through the Ages Section: Spunaugle - 004 11 April 2014 The Refined Roman Society: Analysis of Roman Lamps and a Decorative Lamp Holder 2 In the words of John R. Clarke (2003), “the Romans were not at all like us” (p. 159). Illuminating the rift between modern customs and those of ancient Rome are the characteristics of two ancient discoveries, which even today convey the nuances of their respective cultural and historical contexts: a terracotta lamp and a bronze lamp holder accompanied by two bronze lamps. In the former artifact, the inscription of a lurid sex scene shocks the modern voyeur, unsuspecting of such a display on an object appearing to be of primarily utilitarian and domestic purposes. Upon the latter objects, intricate bronze craftsmanship speaks of innovative manufacturing techniques while the symbolic presence of owl, dormice, and frog figurines hint at the rich cultural exchange that occurred during the Roman Period. In this essay, I will analyze the manufacturing process, use, and artistry evinced by the aesthetic of selected Roman lamps and a Roman lamp holder in order to compare and contrast the objects while shedding light on the broader cultural context they attest to. The incorporation of artistic detail into the fabrication of these ostensibly functional appliances illustrates the sophistication of Roman society as well as the socioeconomic and cultural motifs of the Roman Period. -

The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing, and Fruit Breeding

The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing, and Fruit Breeding Jules Janick Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Purdue University 625 Agriculture Mall Drive West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2010 I. INTRODUCTION A. The Origins of Agriculture B. Origins of Fruit Culture in the Fertile Crescent II. THE HORTICULTURAL ARTS A. Species Selection B. Vegetative Propagation C. Pollination and Fruit Set D. Irrigation E. Pruning and Training F. Processing and Storage III. ORIGIN, DOMESTICATION, AND EARLY CULTURE OF FRUIT CROPS A. Mediterranean Fruits 1. Date Palm 2. Olive 3. Grape 4. Fig 5. Sycomore Fig 6. Pomegranate B. Central Asian Fruits 1. Pome Fruits 2. Stone fruits C. Chinese and Southeastern Asian Fruits 1. Peach 1 2. Citrus 3. Banana and Plantain 4. Mango 5. Persimmon 6. Kiwifruit D. American Fruits 1. Strawberry 2. Brambles 3. Vacciniums 4. Pineapple 5. Avocado 6. Papaya IV. GENETIC CHANGES AND CULTURAL FACTORS IN DOMESTICATION A. Mutations as an Agent of Domestication B. Interspecific Hybridization and Polyploidization C. Hybridization and Selection D. Champions E. Lost Fruits F. Fruit Breeding G. Predicting Future Changes I. INTRODUCTION Crop plants are our greatest heritage from prehistory (Harlan 1992; Diamond 2002). How, where, and when the domestication of crops plants occurred is slowly becoming revealed although not completely understood (Camp et al. 1957; Smartt and Simmonds 1995; Gepts 2003). In some cases, the genetic distance between wild and domestic plants is so great, maize and crucifers, for example, that their origins are obscure. The origins of the ancient grains (wheat, maize, rice, and sorghum) and pulses (sesame and lentil) domesticated in Neolithic times have been the subject of intense interest and the puzzle is being solved with the new evidence based on molecular biology (Gepts 2003). -

Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? the History of Lighting Suggests Not

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Economics of New Goods Volume Author/Editor: Timothy F. Bresnahan and Robert J. Gordon, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-07415-3 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bres96-1 Publication Date: January 1996 Chapter Title: Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not Chapter Author: William D. Nordhaus Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c6064 Chapter pages in book: (p. 27 - 70) Historical Reassessments of Economic Progress This Page Intentionally Left Blank 1 Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not William D. Nordhaus 1.1 The Achilles Heel of Real Output and Wage Measures Studies of the growth of real output or real wages reveal almost two centu- ries of rapid growth for the United States and western Europe. As figure 1.1 shows, real incomes (measured as either real wages or per capita gross national product [ GNP] ) have grown by a factor of between thirteen and eighteen since the first half of the nineteenth century. An examination of real wages shows that they grew by about 1 percent annually between 1800 and 1900 and at an accelerated rate between 1900 and 1950. Quantitative estimates of the growth of real wages or real output have an oft forgotten Achilles heel. While it is relatively easy to calculate nominal wages and outputs, conversion of these into real output or real wages requires calcula- tion of price indexes for the various components of output. -

Gold Finger Ring in the Shape of an Oil Lamp

FRANCK GODDIO UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGIST GOLD FINGER RING IN THE SHAPE OF AN OIL LAMP This finger ring from Canopus is of an extraordinarily high quality. It has a pierced-worked hoop and a bezel in the shape of an oil lamp. The pierced work shows an undulating tendril. No general parallels for the ring are known, but its pierced-worked hoop finds remote parallels in contemporary pierced-worked finger rings from Pantalica in Sicily and Senise in Italy. In addition, similar pierced- worked tendrils reappear on pieces of jewellery from, for example, Kalaat el- Merkab in Syria, the Assiût hoard from Egypt and Lambousa in Cyprus. Interregional style of Late Antique world The pointed, triangular leaves on the Canopus ring find a close parallel on the sides of the settings on a pendant cross from Guarrazar in Spain. This wide geo- graphical distribution of parallels shows that the ring represents the interregional style. It could, therefore, have been made in a workshop in Constantinople or anywhere else in the Late Antique world. A regional attribution would appear impossible. Detail ties ring to Egypt However, there is one detail that ties the ring to Egypt: the bezel in the shape of an oil lamp. Oil lamps played important roles at Christian pilgrimage shrines all over the Byzantine world. Literary sources refer, for example, to oil from the graves of St Andreas, St Menas, St Demetrius, St Martin and from the holy sites in Jerusalem. As stated, the site in Canopus where this ring was found probably belonged to the pilgrimage shrine of SS Cyrus and John. -

Oil Lamp, 60W Incandescent Lamp and Fluorescent Tube

COVER SHEET This is the author version of article published as: Hughes, Stephen W. and Gale, Andrew (2007) A candle in the lab. Physics Education 42(3):pp. 271-274. Copyright 2007 IOP Publishing Accessed from http://eprints.qut.edu.au Candle in the lab 1 A candle in the lab Stephen Hughes and Andrew Gale Department of Physical and Chemical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Gardens Point, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article describes some experiments performed to obtain a spectrum of a candle, oil lamp, 60W incandescent lamp and fluorescent tube. A professional spectrometer was used of a type unlikely to be available to schools so the spectral data is provided as a service to the teaching profession. The brightness and rate of fuel consumption of a candle and oil lamp were also measured. The data obtained could provide the starting point for a discussion on green house gas emissions etc. Introduction An interesting question is how the emission spectra of historic forms of lighting such as the candle and olive oil lamp compare with those of modern forms of lighting such as the incandescent lamp and fluorescent tube. Olive oil lamps have been around for thousands of years. Candles in various forms have also been used over the millennia, initially made from animal fat (tallow) and then beeswax and also paraffin wax in more recent times (Newman 2000). Method A pack of six paraffin candles and a bottle of olive oil were obtained from a local supermarket and a replica oil lamp with a wick obtained from Historic Connections, Shoal Bay, NSW, Australia. -

The Lamps That Lit Their Aw Y Rick Olson Mammoth Cave National Park

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Mammoth Cave Research Symposia 9th Research Symposium 2008 Oct 9th, 10:55 AM The Lamps That Lit Their aW y Rick Olson Mammoth Cave National Park Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/mc_reserch_symp Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Forest Sciences Commons, Geology Commons, Hydrology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Rick Olson, "The Lamps That Lit Their aW y" (October 9, 2008). Mammoth Cave Research Symposia. Paper 6. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/mc_reserch_symp/9th_Research_Symposium_2008/Day_two/6 This is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammoth Cave Research Symposia by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Lamps That Lit Their Way By Rick Olson1 1Division of Science and Resources Management, Mammoth Cave National Park, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky 42259 Abstract The distinctive lanterns used at Mammoth Cave from the middle 1800s until 1938 appear to be a locally derived design. Early whale oil railroad lanterns share some characteristics of the Mammoth Cave lanterns, but L&N Railroad lanterns do not appear to have infl uenced the design. At this time, the design pathway appears to lead from simple open-fl ame tin candle lanterns to the same lantern with a petticoat lamp affi xed in place of the candle, and then fi nally to the font or oil container being soldered onto the lamp base as one unit. This basic Mammoth Cave lantern varied somewhat over the decades, and was probably the primary light source used by Max Kaemper and Ed Bishop in their survey and exploration work. -

Chapter SPS 377 THEATERS and ASSEMBLY HALLS

Published under s. 35.93, Wis. Stats., by the Legislative Reference Bureau. 11 SAFETY AND PROFESSIONAL SERVICES SPS 377.08 Chapter SPS 377 THEATERS AND ASSEMBLY HALLS SPS 377.001 Scope, theaters. SPS 377.16 Fire extinguishers. SPS 377.01 Assembly halls. SPS 377.17 False openings. SPS 377.02 Capacity. SPS 377.18 Motion picture machine booths, general. SPS 377.03 Exits. SPS 377.19 Construction of booth. SPS 377.04 Fire escapes. SPS 377.20 Doors. SPS 377.05 Stairways. SPS 377.21 Openings. SPS 377.06 Exit doors. SPS 377.22 Ventilation of booths. SPS 377.07 Width of exits. SPS 377.23 Relief outlets. SPS 377.08 Seats. SPS 377.24 Electrical wiring. SPS 377.09 Aisles. SPS 377.25 Motion picture machine. SPS 377.10 Obstructions. SPS 377.26 Fire protection in booth; care and use of film. SPS 377.11 Proscenium curtain. SPS 377.27 Portable booths. SPS 377.12 Automatic smoke outlet. SPS 377.28 Strength of floors. SPS 377.13 Lights, oil and gas. SPS 377.29 Maintenance. SPS 377.14 Exit lights and signs. SPS 377.30 Toilet rooms. SPS 377.15 Ventilation. SPS 377.31 Heating plants. Note: Chapter Ind 162 was renumbered chapter ILHR 77 under s. 13.93 (2m) (b) SPS 377.04 Fire escapes. Fire escapes hereafter con- 1., Stats., Register, June, 1995, No. 474; chapter ILHR 77 was renumbered chapter Comm 77 under s. 13.93 (2m) (b) 1., Stats., and corrections made under s. 13.93 (2m) structed shall be stairway fire escapes as described in ss.