0922-Leiocephalus-Personatus.Pdf (4.271Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lizard Inspired Tail for the Dynamic Stabilization of Robotic Bodies

Lizard Inspired Tail for the Dynamic Stabilization of Robotic Bodies A Major Qualify Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science In Mechanical Engineering By Michael Berlied _______________ Approved by: Stephen Nestinger ______________ Date Completed: April 27, 2012 ABSTRACT The purpose of this project was to determine the feasibility of a lizard inspired tail for the dynamic stabilization of robotic bodies during aerial or aggressive maneuvers. A mathematical model was created to determine the effects of various tail designs. A physical model of the tail design was fabricated and used to determine feasibility of the design and evaluate the mathematical model. ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures .............................................................................................................................. v 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 2 3.0 Literature Review...................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Lizard Physiology and Tail -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Microhabitat Selection of the Poorly Known Lizard Tropidurus Lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in the Pantanal, Brazil

ARTICLE Microhabitat selection of the poorly known lizard Tropidurus lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in the Pantanal, Brazil Ronildo Alves Benício¹; Daniel Cunha Passos²; Abraham Mencía³ & Zaida Ortega⁴ ¹ Universidade Regional do Cariri (URCA), Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (CCBS), Departamento de Ciências Biológicas (DCB), Laboratório de Herpetologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Diversidade Biológica e Recursos Naturais (PPGDR). Crato, CE, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7928-2172. E-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) ² Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido (UFERSA), Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (CCBS), Departamento de Biociências (DBIO), Laboratório de Ecologia e Comportamento Animal (LECA), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação (PPGEC). Mossoró, RN, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4378-4496. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Instituto de Biociências (INBIO), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal (PPGBA). Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5579-2031. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Instituto de Biociências (INBIO), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação (PPGEC). Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8167-1652. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Understanding how different environmental factors influence species occurrence is a key issue to address the study of natural populations. However, there is a lack of knowledge on how local traits influence the microhabitat use of tropical arboreal lizards. Here, we investigated the microhabitat selection of the poorly known lizard Tropidurus lagunablanca (Squamata: Tropiduridae) and evaluated how environmental microhabitat features influence animal’s presence. -

NHBSS 061 1G Hikida Fieldg

Book Review N$7+IST. BULL. S,$0 SOC. 61(1): 41–51, 2015 A Field Guide to the Reptiles of Thailand by Tanya Chan-ard, John W. K. Parr and Jarujin Nabhitabhata. Oxford University Press, New York, 2015. 344 pp. paper. ISBN: 9780199736492. 7KDLUHSWLOHVZHUHÀUVWH[WHQVLYHO\VWXGLHGE\WZRJUHDWKHUSHWRORJLVWV0DOFROP$UWKXU 6PLWKDQG(GZDUG+DUULVRQ7D\ORU7KHLUFRQWULEXWLRQVZHUHSXEOLVKHGDV6MITH (1931, 1935, 1943) and TAYLOR 5HFHQWO\RWKHUERRNVDERXWUHSWLOHVDQGDPSKLELDQV LQ7KDLODQGZHUHSXEOLVKHG HJ&HAN-ARD ET AL., 1999: COX ET AL DVZHOODVPDQ\ SDSHUV+RZHYHUWKHVHERRNVZHUHWD[RQRPLFVWXGLHVDQGQRWJXLGHVIRURUGLQDU\SHRSOH7ZR DGGLWLRQDOÀHOGJXLGHERRNVRQUHSWLOHVRUDPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHVKDYHDOVREHHQSXEOLVKHG 0ANTHEY & GROSSMANN, 1997; DAS EXWWKHVHERRNVFRYHURQO\DSDUWRIWKHIDXQD The book under review is very well prepared and will help us know Thai reptiles better. 2QHRIWKHDXWKRUV-DUXMLQ1DEKLWDEKDWDZDVP\ROGIULHQGIRUPHUO\WKH'LUHFWRURI1DWXUDO +LVWRU\0XVHXPWKH1DWLRQDO6FLHQFH0XVHXP7KDLODQG+HZDVDQH[FHOOHQWQDWXUDOLVW DQGKDGH[WHQVLYHNQRZOHGJHDERXW7KDLDQLPDOVHVSHFLDOO\DPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHV,Q ZHYLVLWHG.KDR6RL'DR:LOGOLIH6DQFWXDU\WRVXUYH\KHUSHWRIDXQD+HDGYLVHGXV WRGLJTXLFNO\DURXQGWKHUH:HFROOHFWHGIRXUVSHFLPHQVRIDibamusZKLFKZHGHVFULEHG DVDQHZVSHFLHVDibamus somsaki +ONDA ET AL 1RZ,DPYHU\JODGWRNQRZWKDW WKLVERRNZDVSXEOLVKHGE\KLPDQGKLVFROOHDJXHV8QIRUWXQDWHO\KHSDVVHGDZD\LQ +LVXQWLPHO\GHDWKPD\KDYHGHOD\HGWKHSXEOLFDWLRQRIWKLVERRN7KHERRNLQFOXGHVQHDUO\ DOOQDWLYHUHSWLOHV PRUHWKDQVSHFLHV LQ7KDLODQGDQGPRVWSLFWXUHVZHUHGUDZQZLWK H[FHOOHQWGHWDLO,WLVDYHU\JRRGÀHOGJXLGHIRULGHQWLÀFDWLRQRI7KDLUHSWLOHVIRUVWXGHQWV -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL15, & N AMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 •189 28(1):30–31 • APR 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS CoprophagyFEATURE ARTICLES and Cannibalism in the Cuban . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: GreenOn the Road Anole,to Understanding the Ecology Anolis and Conservation of theporcatus Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Gray Joshua M. Kapfer1840 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A Hypothetical Excursion(Squamata: ............................................................................................................................ Dactyloidae)Robert W. Henderson 198 RESEARCH ARTICLES . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western TexasLuis ....................... F. de Armas Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida .............................................P.O. Box 4327, San AntonioBrian J. deCamposano, los Baños, Kenneth Artemisa L. Krysko, Province Kevin 38100,M. Enge, Cuba Ellen M.([email protected]) Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 oprophagy in. herbivorousMore Than Mammals reptiles, .............................................................................................................................. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Curly-Tailed Lizard SCIENTIFIC NAME There Are Five Species, Leiocephalus Carinatus, L

Artwork by Dominic Cant Curly-tailed Lizard SCIENTIFIC NAME There are five species, Leiocephalus carinatus, L. greenwayi, L. inaguae, L. loxogrammus and L. punctatus and nine sub-species in the Bahamas. DESCRIPTION The curly tailed lizards are medium sized lizards averaging about 18 cm (7 inches) in total length. In the Bahamas they tend to range from brown to grey and have a range of different markings on them depending upon the species. In some species the females are noticeably smaller than the males and some even display a more conspicuous colouration than their male counterparts, particularly when gravid (egg bearing). The most characteristic feature of these lizards is their tail which curls over their back, similar to that of a scorpion, and lends the lizard its name. DIET Curly tails can be considered omnivores, however insects form a major part of their diet. They have been known to eat flowers such as the Rail road vine (Ipomoea pes-caprae), seeds, small fruits, anole lizards, small crustaceans, spiders, roaches, mosquitoes and large quantities of ants. In captivity some males have exhibited a cannibalistic behaviour. REPRODUCTION Male curly tailed lizards are very territorial and fight off rival males. They also display a range of territorial behaviours like head bobbing, tail curling, strutting and inflation of the sides of the neck. The young males begin to exhibit these courtship behaviours Reptiles of the Bahamas at about one year of age. These behaviours will begin in February and usually ends in October when the lizards become generally less active. The leathery eggs are cream coloured and about 25 mm (1 inch) in length with peak hatching time in mid July. -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Limb and Tail Lengths in Relation to Substrate Usage in Tropidurus Lizards

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 248:151–164 (2001) Limb and Tail Lengths in Relation to Substrate Usage in Tropidurus Lizards Tiana Kohlsdorf,1 Theodore Garland Jr.,2 and Carlos A. Navas1* 1Departamento de Fisiologia, IB, Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil 2Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin ABSTRACT A close relationship between morphology divergence in relative tail and hind limb length has been and habitat is well documented for anoline lizards. To test rapid since they split from their sister clade. Being re- the generality of this relationship in lizards, snout-vent, stricted to a single subclade, the difference in body pro- tail, and limb lengths of 18 species of Tropidurus (Tropi- portions could logically be interpreted as either an adap- duridae) were measured and comparisons made between tation to the clade’s lifestyle or simply a nonadaptive body proportions and substrate usage. Phylogenetic anal- synapomorphy for this lineage. Nevertheless, previous ysis of covariance by computer simulation suggests that comparative studies of another clade of lizards (Anolis)as the three species inhabiting sandy soils have relatively well as experimental studies of Sceloporus lizards sprint- longer feet than do other species. Phylogenetic ANCOVA ing on rods of different diameters support the adaptive also demonstrates that the three species inhabiting tree interpretation. J. Morphol. 248:151–164, 2001. canopies and locomoting on small branches have short © 2001 Wiley-Liss, Inc. tails and hind limbs. -

Introduced Amphibians and Reptiles in the Cuban Archipelago

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 10(3):985–1012. Submitted: 3 December 2014; Accepted: 14 October 2015; Published: 16 December 2015. INTRODUCED AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE CUBAN ARCHIPELAGO 1,5 2 3 RAFAEL BORROTO-PÁEZ , ROBERTO ALONSO BOSCH , BORIS A. FABRES , AND OSMANY 4 ALVAREZ GARCÍA 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, Carretera de Varona km 3.5, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba 2Museo de Historia Natural ”Felipe Poey.” Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Habana, La Habana, Cuba 3Environmental Protection in the Caribbean (EPIC), Green Cove Springs, Florida, USA 4Centro de Investigaciones de Mejoramiento Animal de la Ganadería Tropical, MINAGRI, Cotorro, La Habana, Cuba 5Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—The number of introductions and resulting established populations of amphibians and reptiles in Caribbean islands is alarming. Through an extensive review of information on Cuban herpetofauna, including protected area management plans, we present the first comprehensive inventory of introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Cuban archipelago. We classify species as Invasive, Established Non-invasive, Not Established, and Transported. We document the arrival of 26 species, five amphibians and 21 reptiles, in more than 35 different introduction events. Of the 26 species, we identify 11 species (42.3%), one amphibian and 10 reptiles, as established, with nine of them being invasive: Lithobates catesbeianus, Caiman crocodilus, Hemidactylus mabouia, H. angulatus, H. frenatus, Gonatodes albogularis, Sphaerodactylus argus, Gymnophthalmus underwoodi, and Indotyphlops braminus. We present the introduced range of each of the 26 species in the Cuban archipelago as well as the other Caribbean islands and document historical records, the population sources, dispersal pathways, introduction events, current status of distribution, and impacts. -

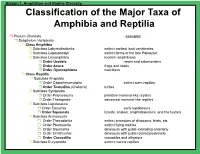

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are