Mate Retention in Caspian Terns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Living (Abiotic) Elements Shape Habitat

Forest Birds Fast Facts LIGHT: Dominated by tall trees, layered canopy = very shady, openings made from a fallen tree provide sunny areas AIR: Trees slow wind, except along forest edges and openings. Shade = cool temps WATER: Fog and rain collect in tree branches and drip to ground. SOIL: Lots of organics (needles, decaying leaves, tree trunks) makes lots of space for air and water. Soil absorbs and holds water like a sponge. Varied Thrush • Slender bill good at gleaning soft foods like insects, pillbugs, snails, worms, fruits and some seeds from ground. • Hops and pauses to look for food. Flips leaves and debris with bill. • Perching feet – three toes forward, hind toe back. • Can sing 2 separate notes at same time and breathe while singing. Common Raven Varied Thrush • Versatile beak. Eats everything from carrion and garbage, to eggs, nestlings, insects, seeds, rodents and fruit. • Strong, sturdy feet and grasping toes to manipulate food and perch. • Acrobatic flight, hops on ground. Uses sight to find food. Northern Flicker • The toes are placed two forward, two back to grip firmly, while the tail feathers are stiff and pointed to help brace while pounding. • Bill is shaped like a chisel. Flickers don’t excavate as much as other types of woodpeckers so have a slightly curved bill and less sharp. Common Raven • Flickers eat insects and are especially fond of ants (flickers will forage on the ground as well as on trees). Probe and explore crevices. • Distinctive flight – flap, dip, flap, dip • Woodpeckers have long, sticky and barbed tongues to extract bugs. -

Caspian Tern Nesting in South Carolina

CASPIAN TERN NESTING IN SOUTH CAROLINA TRAVIS H. McDANIEL and THEODORE A. BECKETT III Although the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) is known to be a year-round resident of South Carolina, the 1970 edition of South Carolina Bird Life (p. 608) lists it as a non-breeding species because no nest or eggs have been collected in the state. E. Milby Burton, T.A. Beckett III, and others who have studied the colonial birds breeding on the islands along the coast of South Carolina during the past 50 years have never found a Caspian Tern nest or chick. Wayne's statement that the species nests in the Royal Tern colonies at Cape Romain (Birds of South Carolina, 1910, p. 4) has been widely accepted, though in retrospect it appears to have been based upon questionable information received from others rather than upon field work actually conducted by the distinguished ornithologist of Oakland Plantation near Mt. Pleasant. On 5 June 1970 Travis H. McDaniel, then manager at Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, made a routine check of nesting birds on Cape Island. As he walked through a Black Skimmer and Gull-billed Tern colony at the south end of the island, he noticed two tern eggs that were appreciably larger than those normally laid by Royal Terns, which are common nesters. During three years at Cape Romain, he had noted that Royal Terns usually lay only one egg. As McDaniel returned to his patrol truck, the birds began to settle back on their eggs. At this time he saw a very large tern dropping down from the air to settle on a nest despite harassing by Black Skimmers. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

WHITE TERN Gygis Alba

WHITE TERN Gygis alba Other: Common White-Tern (1998-2000) G.a. candida (breeding) Fairy Tern, Manu-o-ku G.a. microrhyncha (vagrant) breeding visitor, indigenous; vagrant Three taxonomic groups of White Tern have been recognized, occurring in the tropical s. Atlantic Ocean (G.a. alba group), the Marquesas and Kiribati Is (microrhyncha group), and throughout the remainder of the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, including Micronesia, Wake and Johnston atolls (Amerson and Shelton 1976, Rauzon et al. 2008), and the Hawaiian Islands (candida group). Various ornithologists consider these groups to comprise two or three different species (Pratt et al. 1987, AOU 1998) although, based on reported hybridization between microrhyncha and candida in the Marquesas Is (Holyoak and Thibault 1976), Higgins and Davies (1996) and the AOU (1998) consider these as subspecies groups within a single species. Olson (2005) has recently made a good case for treating microrhyncha and candida as separate species but molecular evidence suggests they should remain a single species (Yeung et al. 2009). See Niethammer and Patrick (1998) for more information on the natural history and biology of this species in the Hawaiian Islands. The great majority of White Terns breeding in the Hawaiian Islands are found in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where they occur on every island group, and number about 25,000 pairs in total population size (Table). The largest numbers by far are found on Midway, where the maturation of Casuarina trees providing nesting sites (cf. Fisher and Baldwin 1946, Rauzon and Kenyon 1984, Harrison 1990, Rauzon 2001; E 16:28-29) has lead to a large population increase, from only a few at the turn of the 20th century (Bryan 1906, Bartsch 1922) to about 3,000 in 1938 (Hadden 1941), to ~20,000 pairs in the mid 2010s. -

Class Three: Breeding

Class Three: Breeding WHERE DO SEABIRDS LAY THEIR EGGS? Nest or no nest? • Some species use no nesting material. E.g., the white tern lays a single egg on an open branch. • Some species use a very little bit of nesting material. E.g., the tufted puffin may use a few pieces of grass and a couple of feathers. • Some species build more substantial nests. E.g. kittiwakes cement their nests onto small cliff shelves by trampling mud and guano to form a base. And, some cormorants build large nests in trees from sticks and twigs. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 1 White tern • Also called fairy tern. • Tropical seabird species. • Lays egg on branch or fork in tree. No nest. • Newly hatched chicks have well developed feet to hang onto the nesting-site. White Tern. © Pillot, via Creative Commons. On the coast or inland? • Most seabird species breed on the coast and offshore islands. • Some species breed fairly far inland, but still commute to the ocean to feed. E.g., kittlitz’s murrelets nest on scree slopes on coastal mountains, and parents may travel more than 70km to their feeding grounds. • Other species breed far inland and never travel to the ocean. E.g., double crested cormorants breed on the coast, but also on lakes in many states such as Minnesota. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 2 NESTING HABITAT (1) Ground Some species breed on the ground. These species tend to breed in areas with little or no predation, such as offshore islands (e.g., terns and gulls) or in the Antarctic (e.g., penguins, albatross). -

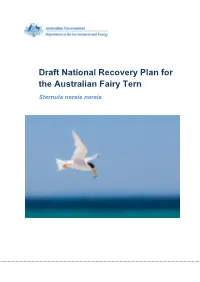

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

Fairy Tern (Sternula Nereis) Conservation in South- Western Australia

FAIRY TERN (STERNULA NEREIS) CONSERVATION IN SOUTH- WESTERN AUSTRALIA A guide prepared by J.N. Dunlop for the Conservation Council of Western Australia. Supported by funding from the Western Australian Government’s State Natural Resource Management Program AckNowleDgemeNts The field research underpinning this guide was supported by the grant of various authorities and in-kind contributions from the Department of Parks & Wildlife (WA) and the Department of Fisheries (WA). The Northern Agricultural Catchment Council (NACC) supported some of the work in the Houtman Abrolhos. Many citizen-scientists have assisted along the way but particular thanks are due to the long-term contribution of Sandy McNeil. Peter Mortimer Unique Earth and Tegan Douglas kindly granted permission for the use of their photographs. The production of the guide to ‘Fairy Tern Conservation in south-western Australia’ was made possible by a grant from WA State NRM Office. This document may be cited as ‘Dunlop, J.N. (2015). Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis) conservation in south-western Australia. Conservation Council (WA), Perth.’ Design & layout: Donna Chapman, Red Cloud Design Published by the Conservation Council of Western Australia Inc. City West Lotteries House, 2 Delhi Street, West Perth, WA 6005 Tel: (08) 9420 7266 Email: [email protected] www.ccwa.org.au © Conservation Council of Western Australia Inc. 2015 Date of publication: September 2015 Tern photos on the cover and the image on this page are by Peter Mortimer Unique Earth. Contents 1. The Problem with Small Terns (Genus: Sternula) 2 2. The Distribution and Conservation Status of Australian Fairy Tern populations 3 3. -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

Notes on the Birds Peculiar to Laysan Island, Hawaiian Group

3S4 V'lS,•ER,Birds of La),san Island. FL AukOct. NOTES ON THE BIRDS PECULIAR TO LAYSAN ISLAND, HAWAIIAN GROUP. 1 BY WALTER K. FISHER. •ølates x_,r_,r-x WE DOnot naturally associateland birds with tiny coral atolls in tropicalseas. It is thereforea strangefact that sucha diminu- tive island as Laysan, and one so remote from continentalshores, should harbor no less than five peculiar species: the Laysan Finch (]klespiza cantans) and Honey-eater (I-Iima•ione freethi), both • drepanidid' birds, the Miller Bird (.4crocefihalusfamiliaris), the LaysanRail (?orzanulapalmeri),and lastly the LaysanTeal (•tnas laysanensis).I usethe term ' land birds' loosely,in con- tradistinctionto sea-fowl,multitudes of which breed here through- out the year. The presenceof these speciesis all the more remarkablebecause none appear on neighboringislands, more or less distant, someof which are very similar to Laysan in structure and flora. Reachingout towardJapan from the main Hawaiian group is a long chainof volcanicrocks, atolls,sand-bars• and sunkenreefs, all insignificantin size and widely separated. The last islet is fully two thousandmiles from Honolulu and about half-way to Yokohama. Beginningat the east,the more importantmembers of this chain are: Bird Island and Necker (tall volcanicrocks), French Frigate Shoals, Gardner Rock, Laysan, Lisiansky, Mid- way, Cure, and Motell. Laysanis eighthundred miles northwest- by-westfrom Honolulu,and is perhapsbest knownas beingthe home of countless albatrosses. We sightedthe island early one morning in May, lying low on the horizon,with a great cloud of sea-birdshovering over it. On all sides the air was lively with terns, albatrosses,and boobies, •These notes were made during a visit of the Fish Commissionsteamer ' Albatross' to Laysan, May 17 to 23, 19o2, and are abridged from a more extendedreport on the avifauna of the i•land• to appearin the Bulletin of the U.S. -

Site Fidelity and Colony Dynaimcs of Caspian Terns Nesting at East

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Stefanie Collar for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Science presented on December 12, 2013. Title: Site Fidelity and Colony Dynamics of Caspian Terns Nesting at East Sand Island, Columbia River Estuary, Oregon, USA. Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Daniel D. Roby Fidelity to breeding sites in colonial birds is an adaptive trait thought to have evolved to enhance reproductive success by reducing search time for breeding habitat, allowing earlier nest initiation, facilitating mate retention, and reducing uncertainty of predator presence and food availability. Studying a seabird that has evolved relatively low colony fidelity, such as the Caspian tern, allowed me to explore the influence of stable nesting habitat on fidelity and nest site selection. The Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) breeding colony on East Sand Island (ESI) in the Columbia River estuary is the largest colony of its kind in the world. This colony has experienced a decade of declining nesting success, culminating with the failure of the colony to produce any young in 2011. The objective of my study was to understand the dynamics of this Caspian tern super-colony by investigating the actions of breeding individuals over two seasons, as well as the behavior of the colony as a whole from 2001-2011. I was interested in (1) the degree of nest site fidelity exhibited by breeding terns in successive years and its relationship to reproductive success, and (2) how the interaction of top-down and bottom-up forces influenced average nesting success across the entire colony, and caused the observed trends in nesting success at the East Sand Island colony from 2001 to 2011. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Pacific Seabirds

PACIFIC SEABIRDS A Publication of the Pacific Seabird Group Volume 36 Number 2 Fall 2009 PACIFIC SEABIRD GROUP Dedicated to the Study and Conservation of Pacific Seabirds and Their Environment The Pacific Seabird Group (PSG) was formed in 1972 due to the need for better communication among Pacific seabird researchers. PSG provides a forum for the research activities of its members, promotes the conservation of seabirds, and informs members and the public of issues relating to Pacific Ocean seabirds and their environment. PSG members include research scientists, conservation professionals, and members of the public from all parts of the Pacific Ocean. The group also welcomes seabird professionals and enthusiasts in other parts of the world. PSG holds annual meetings at which scientific papers and symposia are presented; abstracts for meetings are published on our web site. The group is active in promoting conservation of seabirds, include seabird/fisheries interactions, monitoring of seabird populations, seabird restoration following oil spills, establishment of seabird sanctuaries, and endangered species. Policy statements are issued on conservation issues of critical importance. PSG’s journals are Pacific Seabirds (formerly the PSG Bulletin) and Marine Ornithology. Other publications include symposium volumes and technical reports; these are listed near the back of this issue. PSG is a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Ornithological Council, and the American Bird Conservancy. Annual dues for membership are $30 (individual and family); $24 (student, undergraduate and graduate); and $900 (Life Membership, payable in five $180 installments). Dues are payable to the Treasurer; see the PSG web site, or the Membership Order Form next to inside back cover.