Policy Brief – Accountability for Starvation Crimes: Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/515 安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 日至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日和 31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 6 月 27 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-56095 (C) 231012 241012 *1256095C* S/2012/515 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [Original: Arabic] Wednesday, 27 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 27 June 2012 at 2200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in the area of Qastal. 2. At 0200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in the vicinity of the Industry School in Ra's al-Nab‘, Qatana. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group attacked and detonated explosive devices at the Syrian Ikhbariyah satellite channel building in Darwasha in the vicinity of Khan al-Shaykh, killing Corporal Ma'mun Awasu, Conscript Tal‘at al-Qatalji, Conscript Mash‘al al-Musa and Conscript Abdulqadir Sakin. Several employees were also killed, including Sami Abu Amin, Muhammad Shamsah and employee Zayd Ujayl. Another employee was wounded , 11 law enforcement officers were abducted, and 33 rifles were seized. 4. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group opened on fire on and fired rocket-propelled grenades at a law enforcement checkpoint in Hurnah between Ma‘araba bridge and Tall. -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

S/2012/503 Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/2012/503 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 16 de octubre de 2012 Español Original: inglés Cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas Siguiendo instrucciones de mi Gobierno y en relación con mis cartas de fechas 16 a 20 y 23 a 25 de abril, 7, 11, 14 a 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 y 31 de mayo y 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25 y 27 de junio de 2012, tengo el honor de trasmitir adjunta una lista pormenorizada de las violaciones del cese de la violencia cometidas por grupos armados en Siria el 24 de junio de 2012 (véase el anexo). Agradecería que la presente carta y su anexo se distribuyeran como documento del Consejo de Seguridad. (Firmado) Bashar Ja’afari Embajador Representante Permanente 12-55140 (S) 241012 241012 *1255140* S/2012/503 Anexo de las cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas [Original: árabe] Sunday, 24 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 23 June 2012 at 2020 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in Rif Dimashq. 2. On 23 June 2012 at 2100 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement checkpoints in Shaffuniyah, Shumu' and Umara' in Duma, killing Private Muhammad al-Sa'dah and wounding three soldiers, including a first lieutenant. -

Timeline of Key Events: March 2011: Anti-Government Protests Broke

Timeline of key events: March 2011: Anti-government protests broke out in Deraa governorate calling for political reforms, end of emergency laws and more freedoms. After government crackdown on protestors, demonstrations were nationwide demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad and his government. July 2011: Dr. Nabil Elaraby, Secretary General of the League of Arab States (LAS), paid his first visit to Syria, after his assumption of duties, and demanded the regime to end violence, and release detainees. August 2011: LAS Ministerial Council requested its Secretary General to present President Assad with a 13-point Arab initiative (attached) to resolve the crisis. It included cessation of violence, release of political detainees, genuine political reforms, pluralistic presidential elections, national political dialogue with all opposition factions, and the formation of a transitional national unity government, which all needed to be implemented within a fixed time frame and a team to monitor the above. - The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed of army defectors, led by Col. Riad al-Asaad, and backed by Arab and western powers militarily. September 2011: In light of the 13-Point Arab Initiative, LAS Secretary General's and an Arab Ministerial group visited Damascus to meet President Assad, they were assured that a series of conciliatory measures were to be taken by the Syrian government that focused on national dialogue. October 2011: An Arab Ministerial Committee on Syria was set up, including Algeria, Egypt, Oman, Sudan and LAS Secretary General, mandated to liaise with Syrian government to halt violence and commence dialogue under the auspices of the Arab League with the Syrian opposition on the implementation of political reforms that would meet the aspirations of the people. -

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences

1 The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Alternative Causes of Civil War Onset – Repression and Signals From External Actors: A Comparative Case Study of Bahrain and Syria A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Katherine Ann Kassanitz (under the supervision of Dr. Kevin Koehler) April 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………… 4 A. Background of the Problem………………………………………………..4 B. Statement of the Problem…………………………………………………..7 C. Purpose of the Study……………………………………………………….8 D. Overview of Chapters to Come………………………………………...…15 II. LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………………………17 A. Causes of Civil War Onset………………………………………………..18 1. Grievance Theories……………………………………………………19 2. Greed Theories………………………………………………………...20 3. Repression Theories…………………………………………………...23 4. Transnational Factors and Civil ……………………………………33 III. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK & RESEARCH DESIGN……………….44 A. Why Bahrain and Syria?.............................................................................44 1. Shared Country-Specific Characteristics……………………………...44 2. How these Shared Features Effected their Similar Responses to the Arab Spring Protests…………………………………………………..45 B. Hypotheses………………………………………………………………..49 A. Escalation Theory…………………………………………………….49 B. Signaling Theory……………………………………………………...49 C. Research Design…………………………………………………………..49 IV. BAHRAIN…………………………………………………………………...53 A. Background History………………………………………………………53 -

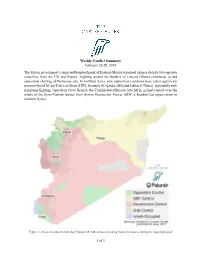

Weekly Conflict Summary

Weekly Conflict Summary February 22-28, 2018 The Syrian government’s siege and bombardment of Eastern Ghouta remained intense despite two separate ceasefires from the UN and Russia. Fighting around the borders of Eastern Ghouta continued, as did opposition shelling of Damascus city. In northern Syria, new opposition coalitions have taken significant territory from Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra), apparently with minimum fighting. Operation Olive Branch, the Turkish-led offensive into Afrin, gained control over the whole of the Syria-Turkish border from Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a Kurdish-led organization in northern Syria). Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 28, with arrows indicating fronts of advances during the reporting period 1 of 3 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 22-28, 2018 Eastern Ghouta Figure 2 - Situation in Eastern Ghouta by February 28 Strikes on opposition-held Eastern Ghouta continued throughout this reporting period. The situation in the besieged area is increasingly dire, with reports of a lack of access to basic nutrition, repeated attacks on hospitals, and mounting civilian casualties. On February 24, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution calling for a 30-day nation-wide ceasefire “without delay”. The resolution was adopted after repeated delays due to disagreements between the US and Russians on the text before the vote. The UN vote was intended to allow emergency aid deliveries to the region’s hardest-hit areas. Despite the resolution, fighting has continued throughout most of Syria, and has been particularly intense in Eastern Ghouta and in the northwestern Afrin region. -

Forgotten Lives Life Under Regime Rule in Former Opposition-Held East Ghouta

FORGOTTEN LIVES LIFE UNDER REGIME RULE IN FORMER OPPOSITION-HELD EAST GHOUTA A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS AND STATISTICS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 2 MAIN AREAS OF CONTROL * 3 MAP OF EAST GHOUTA * 6 MOVEMENT OF CIVILIANS * 8 DETENTION CENTERS * 9 PROPERTY AND REAL ESTATE UPHEAVAL * 11 CONCLUSION Cover Photo: Syrian boy cycles down a destroyed street in Douma on the outskirts of Damascus on April 16, 2018. (LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images) © The Middle East Institute Photo 2: Pro-government soldiers stand outside the Wafideen checkpoint on the outskirts of Damascus on April 3, 2018. (Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/ The Middle East Institute AFP) 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY A “black hole” of information due to widespread fear among residents, East Ghouta is a dark example of the reimposition of the Assad regime’s authoritarian rule over a community once controlled by the opposition. A vast network of checkpoints manned by intelligence forces carry out regular arrests and forced conscriptions for military service. Russian-established “shelters” house thousands and act as detention camps, where the intelligence services can easily question and investigate people, holding them for periods of 15 days to months while performing interrogations using torture. The presence of Iranian-backed militias around East Ghouta, to the east of Damascus, underscores the extent of Iran’s entrenched strategic control over key military points around the capital. As collective punishment for years of opposition control, East Ghouta is subjected to the harshest conditions of any of the territories that were retaken by the regime in 2018, yet it now attracts little attention from the international community. -

Syria Crisis

Syria 0146/Noorani 0146/Noorani Crisis - Monthly humanitarian situation report © UNICEF/NYHQ2014 © 18 MARCH – 17 APRIL 2014: SYRIA, JORDAN, LEBANON, IRAQ, TURKEY AND EGYPT SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights In Syria • During the reporting period, UNICEF participated in four inter-agency convoys in Syria, reaching 2,800 families in Douma, in Rural Damascus; 3,500 families 4,299,600 in Sarmada and 4,000 families in Saraqib in Idleb; as well as 3,000 families in #of children affected Termalleh and 1,000 in Al Ghanto, in Homs. 9,347,000 • The UNICEF-led WASH Sector organized a nationwide workshop from 7-9 # 0f people affected April in Damascus bringing together 150 participants from across the (SHARP 2014) country. During the reporting period, UNICEF and ICRC provided chlorine supplies for the purification of public water supplies, benefitting Outside Syria approximately 16.9 million people. 1,379,986 • On 30 March, Ministry of Health of Iraq declared the first polio outbreak in #of registered refugee children and the country since 2000. UNICEF continues to support the on-going polio children awaiting registration campaigns for all children under 5, with the most recent campaign having been held 6-10 April with preliminary results showing 5.2 million children 2,700,560 vaccinated. # of registered refugees and persons awaiting registration • Preliminary results from the April polio vaccination campaign in Syria show (17 April 2014) an estimated 2.9 million children reached. A round of vaccinations was also undertaken in Lebanon in April with results pending. Syria Appeal 2014* • UNICEF has supported 61,490 children (including 17,957 vulnerable Lebanese children) to enrol in public schools, with over 139,000 children supported by US$ 222.19 million the sector. -

September 2016

www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 1 of 234 Syria & Iraq: September 2016 Copyright 2016 by Ronald B. Standler No copyright claimed for quotations. No copyright claimed for works of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents 1. Chemical Weapons U.N. Security Council begins to ask who used chemical weapons in Syria? ISIL used mustard in Iraq (11 Aug 2015) 2. Syria United Nations Diverted from Syria death toll in Syria now over 301,000 (30 Sep) Free Syrian Army is Leaderless since June 2015 Turkey is an ally from Hell U.S. troops in Syria Recognition that Assad is Winning the Civil War Peace Negotiations for Syria Future of Assad must be decided by Syrians Planning for Peace Negotiations in Geneva New Russia/USA Agreements (9 Sep) U.N. Security Council meeting (21 Sep) Syrian speech to U.N. General Assembly (24 Sep) more meetings and negotiations 22-30 Sep 2016 Friends of Syria meeting in London (7 Sep) ISSG meetings (20, 22 Sep 2016) occasional reports of violations of the Cessation of Hostilities agreement proposed 48-hour ceasefires in Aleppo siege of Aleppo (1-12 Sep} Violations of new agreements in Syria (12-19 Sep) continuing civil war in Syria (20-30 Sep) bombing hospitals in Syria surrender of Moadamiyeh U.N. Reports war crimes prosecution? 3. Iraq Atrocities in Iraq No Criminal Prosecution of Iraqi Army Officers No Prosecution for Fall of Mosul No Prosecution for Rout at Ramadi No Criminal Prosecution for Employing "Ghost Soldiers" www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 2 of 234 Iraq is a failed nation U.S.