50 Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

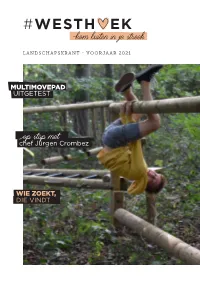

Multimovepad Uitgetest

kom uiten in je streek LANDSCHAPSKRANT - VOORJAAR 2021 MULTIMOVEPAD UITGETEST chefop stapJürgen met Crombez WIE ZOEKT, DIE VINDT VOORWOORD NIEUWE STREKEN KOM BUITEN IN DE WESTHOEK! De lente is in het land! Gedaan met ons binnen te heeft geluk, want die vindt zijn gading op pagina 26 met verstoppen voor de koude – en voor corona. We kunnen tips over ‘de grote goesting’. terug buiten en moeten dat ook doen, want, voor wie het nog niet wist, het is gezond. Lees er alles over op pagina 21. Mogelijkheden genoeg in elk geval. Het nieuwe multimovepad in de Sixtusbossen ontdek je op pagina tien en een overzicht van zowat alle bestaande zoektochten in Jurgen Vanlerberghe de Westhoek staat op pagina 28. Wie de vele inspanningen Voorzitter Regionaal graag doorspoelt met een streekeigen drankje of hapje, Landschap Westhoek WEERZEGGERIJ 01. WEERZEGGERIJ “Rood bij het rijzen, is regen voor de avond” is één 02. DE SINT-NIKLAASKERK IN MESEN © JAN D’HONDT BAD INHOUD van de 601 weerspreuken die Radio 2 weerman Geert 03. LAAT HET ZOEMEN MET Naessens niet alleen bevestigt, maar ook uitlegt in zijn BLOEMEN boek ‘Weerzeggerij’. De spreuken zijn een soort van 3 | NIEUWE STREKEN volksweerkunde. En al is het geen wetenschap, toch houden sommige stellingen steek. ‘Weerzeggerij’ is een 5 | DRIE BIJZONDERE KIJKWANDEN 20 | OPROEP: VRIJWILLIGERS GEZOCHT boek dat verrassende verhalen bij het weer brengt aan de hand van gezegden. 6 | INTERVIEW 21 | IN DE KIJKER: NATUUR MET ZORG www.geertnaessens.be/weerzeggerij | DE FIETS OP 8 24 | ONDER DE LOEP: BEEKVALLEIEN BEKLIM DE SINT-NIKLAASTOREN IN VEURNE… Geniet van het prachtig panoramisch 360° uitzicht | UITGETEST! MULTIMOVEPAD | OP STAP MET.. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

St Boniface Antwerpen

St Boniface Antwerpen A history of the Anglican Church in Antwerp Introduction St. Boniface Church has roots going back to the 16th Century, deep into Antwerp's history and that of Anglicanism. Antwerp then was a metropolis of world class, the most important trading and financial centre in Western Europe, as a seaport, the spice trade, money and wool markets. There are many paths down which one can go in this history of the Church. In 2010, our church celebrated its centenary and work on much needed major repairs, to preserve the heritage of this beautiful Church, commenced. A few years ago, St. Boniface became a recognized State Monument, but even before that it was, and is, always open for pre-arranged visits and conducted tours. Prior to April 1910, the British Community's Services were held at the "Tanner's Chapel" loaned to them by the authorities, and named from the French "Chapelle des Tanneurs" (Huidevettersstraat), after the street of that name, and this remained the Anglican Church in Antwerp from 1821 until St. Boniface was built and consecrated. Building St. Boniface in the Grétrystraat The history of St. Boniface as it now stands began on June 23rd, 1906, in the presence of a large number of Belgian and British notables, when the foundation stone of the Church was laid with much ceremony, by the British Minister to Belgium, Sir Arthur Hardinge. This ceremony was followed by a public lunch at which more than 70 persons were present and where acknowledgement was made of the debt owed by the community to Mr. -

Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 Hugh Dunthorne Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83747-7 - Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 Hugh Dunthorne Frontmatter More information Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 England’s response to the Revolt of the Netherlands (1568–1648) has been studied hitherto mainly in terms of government policy, yet the Dutch struggle with Habsburg Spain affected a much wider commu- nity than just the English political elite. It attracted attention across Britain and drew not just statesmen and diplomats but also soldiers, merchants, religious refugees, journalists, travellers and students into the confl ict. Hugh Dunthorne draws on pamphlet literature to reveal how British contemporaries viewed the progress of their near neigh- bours’ rebellion, and assesses the lasting impact which the Revolt and the rise of the Dutch Republic had on Britain’s domestic history. The book explores affi nities between the Dutch Revolt and the British civil wars of the seventeenth century – the fi rst major challenges to royal authority in modern times – showing how much Britain’s chang- ing commercial, religious and political culture owed to the country’s involvement with events across the North Sea. HUGH DUNTHORNE specializes in the history of the early modern period, the Dutch revolt and the Dutch republic and empire, the his- tory of war, and the Enlightenment. He was formerly Senior Lecturer in History at Swansea University, and his previous publications include The Enlightenment (1991) and The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Britain and the Low Countries -

Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2014 Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism Jose Manuel Izquierdo University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Izquierdo, Jose Manuel, "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jose Manuel Izquierdo entitled "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Micheline van Riemsdijk, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Derek H. Alderman, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jose Manuel Izquierdo August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jose Manuel Izquierdo All rights reserved. -

Bestuursmemoriaal 2020 - 05

BESTUURSMEMORIAAL 2020 - 05 VU.G. Anthierens, Provinciegriffier, Koning Leopold III-laan 41, 8200 Sint-Andries Inhoud Bestuursmemoriaal nummer 2020 - 05 GEMEENTELIJKE POLITIEVERORDENINGEN EN REGLEMENTEN 22. Overzicht van de gemeentelijke politieverordeningen en reglementen van de eerste jaarhelft van 2020 PROVINCIALE REGLEMENTEN 23. Vaststellen van de eerste aanpassing van het meerjarenplan 2020-2025 24. Goedkeuren van de jaarrekening 2019 LIJST BESLUITEN PROVINCIERAAD 25. Lijst van de besluiten van de provincieraad van 18 juni 2020 112 BESTUURSMEMORIAAL 2020 - 05 VU.G. Anthierens, Provinciegriffier, Koning Leopold III-laan 41, 8200 Sint-Andries GEMEENTELIJKE POLITIEVERORDENINGEN EN REGLEMENTEN 22. Overzicht van de politieverordeningen en reglementen van de eerste jaarhelft van 2020 Gemeente Onderwerp Vastgesteld door Datum Harelbeke Politieverordening in toepassing van art. 134, par. 1 van de nieuwe Burgemeester 16.03.2020 gemeentewet betreffende het afgelasten van de gemeenteraad van 16.03.2020 i.k.v. de strijd tegen het coronavirus (covid-19) Harellbeke Politieverordening in toepassing van art. 134; par. 1 van de nieuwe Burgemeester 31.03.2020 gemeentewet betreffende het besloten en virtueel karakter van de gemeenteraad van 20.04.2020 i.k.v. de strijd tegen het coronavirus (Covid-19) Harelbeke Politieverordening betreffende het besloten en virtueel karakter van Burgemeester 24.04.2020 de gemeenteraad van 20.04.2020 en de op die datum aansluitende OCMW-raaad Houthulst Politiereglement betreffende het inrichten van de afstellingsitten College van 30.01.2020 voor de Ypres Rally te Merkem op dinsdag 11 februari burgemeester en schepenen Houthulst Politiereglement i.v.m. éénrichting in de Steenstraat van 02/03 tot College van 06.02.2020 en met 31/05/2020 burgemeester en schepenen Houthulst Politiereglement i.v.m. -

The Meaning and Significance of 'Water' in the Antwerp Cityscapes

The meaning and significance of ‘water’ in the Antwerp cityscapes (c. 1550-1650 AD) Julia Dijkstra1 Scholars have often described the sixteenth century as This essay starts with a short history of the rise of the ‘golden age’ of Antwerp. From the last decades of the cityscapes in the fine arts. It will show the emergence fifteenth century onwards, Antwerp became one of the of maritime landscape as an independent motif in the leading cities in Europe in terms of wealth and cultural sixteenth century. Set against this theoretical framework, activity, comparable to Florence, Rome and Venice. The a selection of Antwerp cityscapes will be discussed. Both rising importance of the Antwerp harbour made the city prints and paintings will be analysed according to view- a major centre of trade. Foreign tradesmen played an es- point, the ratio of water, sky and city elements in the sential role in the rise of Antwerp as metropolis (Van der picture plane, type of ships and other significant mari- Stock, 1993: 16). This period of great prosperity, however, time details. The primary aim is to see if and how the came to a sudden end with the commencement of the po- cityscape of Antwerp changed in the sixteenth and sev- litical and economic turmoil caused by the Eighty Years’ enteenth century, in particular between 1550 and 1650. War (1568 – 1648). In 1585, the Fall of Antwerp even led The case studies represent Antwerp cityscapes from dif- to the so-called ‘blocking’ of the Scheldt, the most im- ferent periods within this time frame, in order to examine portant route from Antwerp to the sea (Groenveld, 2008: whether a certain development can be determined. -

Linkebeek 1.83% Provincie Vlaams-Brabant Vlaams Gewest Arrondissement Leuven Diest 1.83%

Geografische indicatoren (gebaseerd op Census 2011) De referentiedatum van de Census is 01/01/2011. Filters: Nationaliteit van een niet-EU land België Gewest Provincie Arrondissement Gemeente Vlaams Gewest Provincie Limburg Arrondissement Tongeren Herstappe . Provincie Luxemburg Arrondissement Neufchâteau Wellin 0.10% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Verviers Amel 0.15% Provincie Namen Arrondissement Dinant Gedinne 0.20% Vlaams Gewest Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Kortrijk Spiere-Helkijn 0.24% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Honnelles 0.24% Waals Gewest Provincie Luxemburg Arrondissement Neufchâteau Libin 0.25% Vlaams Gewest Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Veurne Alveringem 0.26% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Borgworm Braives 0.26% Arrondissement Diksmuide Lo-Reninge 0.27% Vlaams Gewest Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Roeselare Staden 0.27% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Doornik Rumes 0.27% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Hoei Clavier 0.29% Provincie Luxemburg Arrondissement Virton Meix-devant-Virton 0.29% Vlaams Gewest Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Diksmuide Kortemark 0.30% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Thuin Momignies 0.30% Vlaams Gewest Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Brugge Damme 0.31% Provincie Luik Arrondissement Hoei Nandrin 0.31% Waals Gewest Provincie Luxemburg Arrondissement Aarlen Attert 0.31% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Ieper Zonnebeke 0.32% Vlaams Gewest Zwalm 0.33% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement -

Reconstructions of the Past in Belgium and Flanders

Louis Vos 7. Reconstructions of the Past in Belgium and Flanders In the eyes of some observers, the forces of nationalism are causing such far- reaching social and political change in Belgium that they threaten the cohesion of the nation-state, and may perhaps lead to secession. Since Belgian independ- ence in 1831 there have been such radical shifts in national identity – in fact here we could speak rather of overlapping and/or competing identities – that the political authorities have responded by changing the political structures of the Belgian state along federalist lines. The federal government, the Dutch-speaking Flemish community in the north of Belgium and the French-speaking commu- nity – both in the southern Walloon region and in the metropolitan area of Brus- sels – all have their own governments and institutions.1 The various actors in this federal framework each have their own conceptions of how to take the state-building process further, underpinned by specific views on Belgian national identity and on the identities of the different regions and communities. In this chapter, the shifts in the national self-image that have taken place in Belgium during its history and the present configurations of national identities and sub-state nationalism will be described. Central to this chapter is the question whether historians have contributed to the legitimization of this evolving consciousness, and if so, how. It will be demonstrated that the way in which the practice of historiography reflects the process of nation- and state- building has undergone profound changes since the beginnings of a national his- toriography. -

The Lion, the Rooster, and the Union: National Identity in the Belgian Clandestine Press, 1914-1918

THE LION, THE ROOSTER, AND THE UNION: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE BELGIAN CLANDESTINE PRESS, 1914-1918 by MATTHEW R. DUNN Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for departmental honors Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Andrew Denning _________________________ Dr. Nathan Wood _________________________ Dr. Erik Scott _________________________ Date Abstract Significant research has been conducted on the trials and tribulations of Belgium during the First World War. While amateur historians can often summarize the “Rape of Belgium” and cite nationalism as a cause of the war, few people are aware of the substantial contributions of the Belgian people to the war effort and their significance, especially in the historical context of Belgian nationalism. Relatively few works have been written about the underground press in Belgium during the war, and even fewer of those works are scholarly. The Belgian underground press attempted to unite the country's two major national identities, Flemings and Walloons, using the German occupation as the catalyst to do so. Belgian nationalists were able to momentarily unite the Belgian people to resist their German occupiers by publishing pro-Belgian newspapers and articles. They relied on three pillars of identity—Catholic heritage, loyalty to the Belgian Crown, and anti-German sentiment. While this expansion of Belgian identity dissipated to an extent after WWI, the efforts of the clandestine press still serve as an important framework for the development of national identity today. By examining how the clandestine press convinced members of two separate nations, Flanders and Wallonia, to re-imagine their community to the nation of Belgium, historians can analyze the successful expansion of a nation in a war-time context. -

Time and Historicity As Constructed by the Argentine Madres De Plaza De Mayo and Radical Flemish Nationalists Berber Bevernage A; Koen Aerts a a Ghent University

This article was downloaded by: [Bevernage, Berber] On: 23 November 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917057581] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Social History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713708979 Haunting pasts: time and historicity as constructed by the Argentine Madres de Plaza de Mayo and radical Flemish nationalists Berber Bevernage a; Koen Aerts a a Ghent University, Online publication date: 20 November 2009 To cite this Article Bevernage, Berber and Aerts, Koen(2009) 'Haunting pasts: time and historicity as constructed by the Argentine Madres de Plaza de Mayo and radical Flemish nationalists', Social History, 34: 4, 391 — 408 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03071020903256986 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071020903256986 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Opening up the Planning Landscape

PLANNING LANDSCAPE OPENING UP THE BEITSKE BOONSTRA PETER DAVIDS ANNELIES STAESSEN Over the past 15 years, the actor-relational approach of planning grew and evolved from an interactive system between leading actors, factors of importance within evolving institutional OPENING UP settings to a co-evolutionary perspective on spatial planning. The various actor-relational and complexity-sensitive research and applications in the Flemish and Dutch landscape and THE PLANNING beyond collected in this book demonstrate how this actor- relational approach of planning is not a fixed methodology but rather an attitude which (co-)evolves depending on specific the Netherlands and Beyond to Spatial Planning in Flanders, 15 years of Actor-relational Approaches LANDSCAPE themes, insights and surroundings. Therewith, the book forms a showcase of the wide applicability of the actor-relational approach in enduring or deadlocked planning processes. The combination of scientific exposés, column-like retrospective intermezzos and concise boxes is structured according to the main 15 years of Actor-relational Approaches ingredients of the approach: actors, relations and approaches. to Spatial Planning in Flanders, The book offers an exploration of the consistencies in its (theore- tical) insights, addresses future challenges in actor-relational and the Netherlands and Beyond complexity-sensitive planning research and discusses its potential for future planning in the Eurodelta region and beyond. ANNELIES STAESSEN PETER DAVIDS BEITSKE BOONSTRA OPENING UP THE PLANNING