A-Midsummer-Nights-Dream-Teacher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

EDUCATION RESOURCE Education rnzb.org.nz facebook.com/nzballet THE VODAFONE SEASON OF NATIONAL SPONSOR SUPPORTED BY MAJOR SUPPORTER SUPPORTING EDUCATION CONTENTS Curriculum 3 Ballet based on Shakespeare’s play 4 A Midsummer Night’s Dream ‘Shakespeare’s comic (world premiere) 5 The story of A Midsummer Night’s Dream 7 masterpiece of love, A brief synopsis for the classroom 7 Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer mistaken identities Night’s Dream 8 and magical mayhem A new score for a new ballet 9 A Midsummer Night’s Dream set and has been the source of costumes 11 Q & A with set and costume designer inspiration for artists of Tracy Grant Lord 13 Introducing lighting designer Kendall Smith 15 all genres for centuries. Origin of the fairies 16 My aim is to create A Midsummer Night’s Dream word puzzle 17 Identify the characters with their something fresh and emotions 18 Ballet timeline 20 vibrant, bubbling with all Let’s dance! 21 Identifying the two groups of characters the delight and humour through movement 23 that Shakespeare offers Answers 24 us through the wonderful array of characters he conjured up. As with any great story I want to take my audience on a journey so that every individual can have their own Midsummer Night’s Dream.” LIAM SCARLETT 2 CURRICULUM In this unit you and your students will: LEARNING OBJectives FOR • Learn about the elements that come Levels 7 & 8 together to create a theatrical ballet experience. Level 7 students will learn how to: • Identify the processes involved in making a • Understand dance in context – Investigate theatre production. -

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

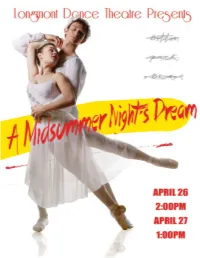

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

Miami City Ballet 37

Miami City Ballet 37 MIAMI CITY BALLET Charleston Gaillard Center May 26, 2:00pm and 8:00pm; Martha and John M. Rivers May 27, 2:00pm Performance Hall Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez Conductor Gary Sheldon Piano Ciro Fodere and Francisco Rennó Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra 2 hours | Performed with two intermissions Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1980) Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Music Charles Gounod Staging Ben Huys Costume Design Karinska Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Katia Carranza, Renato Penteado, Nathalia Arja Emily Bromberg, Ashley Knox Maya Collins, Samantha Hope Galler, Jordan-Elizabeth Long, Nicole Stalker Alaina Andersen, Julia Cinquemani, Mayumi Enokibara, Ellen Grocki, Petra Love, Suzette Logue, Grace Mullins, Lexie Overholt, Leanna Rinaldi, Helen Ruiz, Alyssa Schroeder, Christie Sciturro, Raechel Sparreo, Christina Spigner, Ella Titus, Ao Wang Pause Carousel Pas de Deux (1994) Choreography Sir Kenneth MacMillan Music Richard Rodgers, Arranged and Orchestrated by Martin Yates Staging Stacy Caddell Costume Design Bob Crowley Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Jennifer Lauren, Chase Swatosh Intermission Program continues on next page 38 Miami City Ballet Concerto DSCH (2008) Choreography Alexei Ratmansky Music Dmitri Shostakovich Staging Tatiana and Alexei Ratmansky Costume Design Holly Hynes Lighting Design Mark Stanley Dancers Simone Messmer, Nathalia Arja, Renan Cerdeiro, Chase Swatosh, Kleber Rebello Emily Bromberg and Didier Bramaz Lauren Fadeley and Shimon Ito Ashley Knox and Ariel Rose Samantha -

Award Syllabus

South Island Ballet Award and PW Dance & Sportswear Junior South Island Ballet Award Friday 20th May to Sunday 22nd May 2016 | CHRISTCHURCH [Date and Time] [Street Address] Award Syllabus Table of Contents Page Award Overview 3 Conditions of Entry 4 Entry Form 5 Junior Criteria 6 Senior Criteria 7-8 Adjudicators 9-11 Sponsorship 12-13 Hotel Flyer 14 SOUTH ISLAND BALLET AWARD 2016 The Christchurch Ballet Society is proud to present the South Island Ballet Award for 2016. This major event will be the highlight of the South Island competition dance calendar. The Christchurch Ballet Society is offering a significant cash incentive to talented and dedicated dancers whose tuition is or has been provided by a ballet tutor located within the South Island. It is intended that by offering a cash scholarship this will assist the recipients of the award in furthering their training and studies in classical ballet. th nd Friday 20 May to Sunday 22 May 2016 | CHRISTCHURCH Senior Award Junior Award First Place $5000 Tuition Scholarship First Place $3000 Tuition Scholarship Silver Challenge Cup and Sash Silver Challenge Cup and Sash Second Place $2000 Tuition Scholarship Second Place $1000 Tuition Scholarship and Sash and Sash Third Place $1000 Tuition Scholarship Third Place $500 Tuition Scholarship and Sash and Sash **Finalists may also receive a cash incentive** Senior Age Group Junior Age Group 15 to 19 years as at 20th May 2016 12 to 14 years as 20th May 2016 ENTRY FEE and CLOSING DATE An entry fee of $150 (Non-refundable) will be required upon receipt of entry form. -

The Balanchine Trust: Dancing Through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing

Volume 6 Issue 2 Article 2 1999 The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing Cheryl Swack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Cheryl Swack, The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing, 6 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 265 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Swack: The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licen THE BALANCHINE TRUST: DANCING THROUGH THE STEPS OF TWO-PART LICENSING CHERYL SWACK* I. INTRODUCTION A. George Balanchine George Balanchine,1 "one of the century's certifiable ge- * Member of the Florida Bar; J.D., University of Miami School of Law; B. A., Sarah Lawrence College. This article is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Allegra Swack. 1. Born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Russia of Georgian parents, Georgi Melto- novich Balanchivadze entered the Imperial Theater School at the Maryinsky Thea- tre in 1914. See ROBERT TRAcy & SHARON DELONG, BALANci-NE's BALLERINAS: CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MUSES 14 (Linden Press 1983) [hereinafter TRAcY & DELONG]. His dance training took place during the war years of the Russian Revolution. -

East by Northeast the Kingdom of the Shades (From Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena

2013/2014 La Bayadère Act II | Airs | Donizetti Variations Photo by Paul B. Goode, courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Company East by Spring Ballet Northeast Seven Hundred Fourth Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet: East by Northeast The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena Donizetti Variations Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Gaetano Donizetti Staged by Sandra Jennings Airs Choreography by Paul Taylor Music by George Frideric Handel Staged by Constance Dinapoli Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Ninth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Ninth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Staged by Glenda Lucena Music by Ludwig Minkus Orchestration by John Lanchbery* Lighting Re-created by Patrick Mero Glenda Lucena, Ballet Mistress Violette Verdy, Principals Coach Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Premiere: February 4, 1877 | Imperial Ballet, Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St. Petersburg Grand Pas de Deux Nikiya, a temple dancer . Alexandra Hartnett Solor, a warrior. Matthew Rusk Pas de Trois (3/28 and 3/29 mat.) First Solo. Katie Zimmerman Second Solo . Laura Whitby Third -

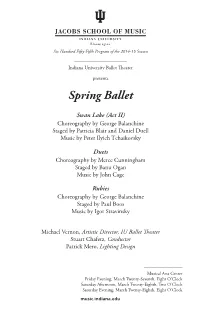

Spring Ballet

Six Hundred Fifty-Fifth Program of the 2014-15 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Duets Choreography by Merce Cunningham Staged by Banu Ogan Music by John Cage Rubies Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Paul Boos Music by Igor Stravinsky Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Seventh, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Eighth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine* ©The George Balanchine Trust Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Original Scenery and Costumes by Rouben Ter-Arutunian Premiere: November 20, 1951 | New York City Ballet City Center of Music and Drama Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Violette Verdy, Principal Coach Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Odette, Queen of the Swans Raffaella Stroik (3/27) Elizabeth Edwards (3/28 mat ) Natalie Nguyen (3/28 eve ) Prince Siegfried Matthew Rusk (3/27) Colin Ellis (3/28 mat ) Andrew Copeland (3/28 eve ) Swans Bianca Allanic, Mackenzie Allen, Margaret Andriani, Caroline Atwell, Morgan Buchart, Colleen Buckley, Danielle Cesanek, Leah Gaston (3/28), Bethany Green (3/28 eve ), Rebecca Green, Cara Hansvick -

Interpreting Musical Structure Through Choreography in Gershwin's

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-23-2019 Music in Motion: Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s "An American in Paris" Spencer Reese University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Reese, Spencer, "Music in Motion: Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s "An American in Paris"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2172. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/2172 Abstract Music in Motion Interpreting Musical Structure through Choreography in Gershwin’s An American in Paris Spencer Matthew Reese, D.M.A. University of Connecticut, 2019 This dissertation explores the relationship between the theoretic interpretation of music (through analysis of a score) and the kinesthetic interpretation of it (through dance). While compelling choreography often evokes the same expressive qualities as a score, music and dance each have expressive and structural components. This study looks beyond expressive unity to examine how formal elements of a musical score are embodied in a choreographic interpretation of it. George Gershwin’s now-iconic symphonic poem An American in Paris, while conceived as concert music, was almost immediately interpreted in dance onstage. It also inspired larger narrative works, including a film choreographed by Gene Kelly and a musical helmed by Christopher Wheeldon. When a score is written for dance, the logistical considerations of choreography likely influence the piece’s composition. But in the case of Paris, the structural details of the music itself have consistently given artists the impression that it is danceable. Gershwin’s life and musical style are examined, including his synthesis of popular and Western art music. -

The Royal Ballet Celebrates American Choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins

27 May 2021 #OurHouseToYourHouse Fundraising for our future The Royal Ballet celebrates American choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins The Royal Ballet celebrates the rich history of American ballet in classic works by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, two choreographic giants of the 20th century. Balanchine and Robbins open’s on 4 June and is live streamed on 11 June at 7.30pm priced £16. The programme includes two classic works by Balanchine; Apollo and Tchaikovsky Pas De Deux. Apollo was created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1928 and is regarded as a masterpiece of neoclassicism in its striking depiction of the young god of music and his three muses. Set to music by Igor Stravinsky the ballet was last performed by The Company in 2014. In 1960 Balanchine created Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux for New York City Ballet. The ballet is a showcase of technical challenges and bravura and is set to a long-lost movement from Tchaikovsky’s original score for Swan Lake. Jerome Robbins played a crucial role in the development of American ballet as a contemporary of Balanchine and as an influential figure in Broadway. His 1969 ballet Dances at a Gathering is an ode to pure dance, set to music by Chopin. While plotless, the intimacy of the ballet creates a powerful sense of community which promises to resonate powerfully with audiences and dancers again following its revival in 2020 just before lockdown. This programme features a host of debuts by Royal Ballet Principals Fumi Kaneko, Yasmine Naghdi, Matthew Ball, Cesar Corrales and Vadim Muntagirov and First Soloists Claire Calvert, Melissa Hamilton, Mayara Magri, Anna Rose O’Sullivan and Reece Clarke The event will be broadcast live via the Royal Opera House website on Friday 11 June at 7.30pm, priced at £16.00 per household and will be available to watch on demand until 10 July. -

The Symphony in C Saga

Volume IX No. 4 Summer 2015 From the Dance Notation Bureau INSIDE THIS ISSUE THE SYMPHONY IN C SAGA by Ann Hutchinson Guest • The Symphony in C Saga For a long time the USA copyright law did not include dance. Dance was Dance Notation Bureau Library considered as a form of ballroom dance, which the copyright powers considered to Monday - Friday 10 am – 5 pm be below the dignity of being given copyright protection. If considered at all, it Advance Notification by Phone/Email came under the heading of a Dramatico-musical composition. It had to have a Recommended story. Then the copyright law changed; dance was considered as a serious art, but 111 John Street, Suite 704 Pure Dance choreography, abstract composition without a story, was still New York, NY 10038 debatable. Phone: 212/ 571-7011 Fax: 212/571 -7012 Copyright registration of Balanchine’s ballet Symphony in C became quite a saga. Email: [email protected] But let us go back to the beginning. Website: www.dancenotation.org Facebook: NOTATING FOR BALANCHINE 1948 -1961 www.facebook.com/dancenotationbureau Library News is published four times a year John Coleman took my hand. "Come," he said, "You've got to meet Balanchine!" in New York It was the Fall of 1946, I was at the San Francisco Opera House seeing a performance of the Ballets Russes. John Coleman, musician, composer, teacher, Editors: and expert on Dalcroze, was a crazy, endearing man who knew everyone. He had Senta Driver worked with Balanchine and also with Kurt Jooss and so knew me from Dartington Mei-Chen Lu Hall days.