Commence to Dancing by David Vaughan Introduced by Alastair Macaulay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Online

6qNin [Download free ebook] Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Online [6qNin.ebook] Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Pdf Free Hans Werner Henze ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4990267 in Books 2015-10-30Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .31 x 5.51l, .54 #File Name: 185273095176 pages | File size: 15.Mb Hans Werner Henze : Ondine - Diary of a Ballet before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Ondine - Diary of a Ballet: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Dear Hans, thanks for sharing, you're the cat's pajamas. Better, you're The Cat's Fugue.By J. FaulkThese extracts, melded together, from the composer's diary were published in Germany in 1959 and in English in 2003.In 1957 Ashton and Henze meet in Ischia to convert the old German folktale Undine into a ballet scenario that choreographer, composer, and the great ballerina Fonteyn can find inspiring (as well as the traditionalist London audience). The tale commences in the hut of a fisherman and his wife and their foundling daughter, actually an ondine. The girl immediately falls in love (so far as an ondine can) with the guest Knight. It takes Ashton and Henze a long time to jettison this commonplace setting. Meanwhile, Henze's diary wanders off into appreciation of Italian life.Henze goes to London to write the music and his diary shares the milieu with us. Designer Lila De Nobili comes over from Paris and joins in the ever-shifting ideas. -

Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro What Constitutes a Dance?: Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies By: Ann Dils Dils, A. (1993) What Constitutes a Dance?: Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies, Dance Research Journal 24 (2), 17-31. Made available courtesy of University of Illinois Press: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/journals/drj.html ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document These papers were originally given as a panel entitled What Constitutes a Dance at the 1989 Congress on Research in Dance Conference in Williamsburg, Virginia. Panelists selected Antony Tudor's 1937 Dark Elegies as a case study and basis for examining general questions regarding elements to be considered in identifying a dance work. Several issues and occurrences inspired panel members, such as recent interest in revivals of dance works from the beginning of this century and scholarly debate about issues related to directing dance from Labanotation scores. While Nelson Goodman's 1968 book Languages of Art served as a theoretical springboard for discussion, Judy Van Zile's 1985-86 article "What is the Dance? Implications for Dance Notation" proved a thought-provoking precedent for this investigation. The term "constitutive" comes from Goodman's work and is one of several ideas discussed in Languages of Art that are important to dance notation. For Goodman, the purpose of notation is to identify a work and specify its essential properties. These essential properties are constitutive; el- ements of a work that can be varied without disturbing the work's identity are "contingent" (p. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: a Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2018 The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries Rachel Smith University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Rachel, "The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries" (2018). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers 1 The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: A Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries Rachel Smith Departmental Honors Thesis University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Health and Human Performance Examination Date: March 22, 2018 ________________________________ ______________________________ Shewanee Howard-Baptiste Burch Oglesby Associate Professor of Exercise Science Associate Professor of Exercise Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ________________________________ Liz Hathaway Assistant Professor of Exercise -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-20-2006 Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Liane Fisher Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Dance Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Liane, "Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory" (2006). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 41. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Thesis Skidmore College Liane Fisher March 2006 Advisor: Isabel Brown Reader: Marc Andre Wiesmann Table of Contents Abstract .............................. ... .... .......................................... .......... ............................ ...................... 1 Chapter 1 : Introduction .. .................................................... ........... ..... ............ ..... ......... ............. 2 My thologyand Ballet ... ....... ... ........... ................... ....... ................... ....... ...... .................. 7 The Labyrinth My thologies .. ......................... .... ................. .......................................... -

Ourhousetoyourhouse Royal Opera House Announces New Friday Premiere Stream: the Royal Ballet’S the Dream (2017)

17 March 2021 #OurHouseToYourHouse Royal Opera House announces new Friday Premiere stream: The Royal Ballet’s The Dream (2017) The Royal Opera House is delighted to continue its #OurHouseToYourHouse programme, featuring online broadcasts that can be accessed by audiences around the world for just £3. Join us on Friday 19 March at 7pm GMT as we stream The Dream (2017). Frederick Ashton’s delightful interpretation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a classic of The Royal Ballet’s repertory, and this production, recorded in 2017, features music from Felix Mendelssohn performed by the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House and designs from David Walker. Showcasing the extraordinary talents of dancers of The Royal Ballet, this recording stars Principal dancers Akane Takada as Titania and Steven McRae as Oberon. Also featured are First Soloist Valentino Zucchetti as Puck and Principal Character Artist Bennet Gartside as Bottom. Titles currently available to view via stream.roh.org.uk include La Fille mal gardée (The Royal Ballet, 2015), Il trittico (The Royal Opera, 2011), Raymonda Act III (The Royal Ballet, 2019), Tony and the Young Artists (The Royal Opera, 2021) and The Sleeping Beauty (The Royal Ballet, 2020). As part of our ongoing partnership with the BBC, Royal Opera House content continues to be available via BBC Sounds and BBC iPlayer. The Royal Opera’s 2018 performance of Wagner’s Ring Cycle in Keith Warner’s acclaimed production is available to listen to again in full. Presented by Tom Service, these performances feature Antonio Pappano conducting the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House and a stellar cast including soprano Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde; baritone John Lundgren as Wotan; mezzo- soprano Sarah Connolly as Fricka; and tenor Stefan Vinke as Siegfried, among others. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

Articles Blog Posts

More Than Words: Designs, Dance, and Graphic Notation in the Performing Arts Society of American Archivists, August 2021 / Virtual Tour Library of Congress, Music Division Resources Articles Library of Congress Magazine Brilliant Broadway: Volume 7, No. 3, May-June 2018: Christopher Hartten, “Brilliant by Design” Library of Congress Magazine - May/June 2018 (loc.gov) Blog Posts: In the Muse Albro, Sylvia. Undated. “Conservation Treatment of Seven Engraved Music Motets.” https://www.loc.gov/preservation/conservators/musicmotets/index.html Baumgart, Emily. May 29, 2021. “Cicada Terrible Freedom.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/05/cicada-terrible-freedom/ ______. March 11, 2021. "A New LGBTQ+ Resource from the Library of Congress Music Division" https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/03/a-new-lgbtq-resource-from-the-library-of-congress-music- division Doyle, Kaitlin (Kate). July 9, 2016. “Discovering the Music Within Our Dance Collections: Composer Lucia Dlugoszewski and the Erick Hawkins Dance Company.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2016/09/discovering-the-music-within-our-dance-collections- composer-lucia-dlugoszewski-and-the-erick-hawkins-dance-company/ Hartten, Chris. September 6, 2011. “The Bad Boy of Music.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/09/the-bad-boy-of-music/ ______. February 19, 2015. “Chameleon as Composer: The Colorful Life and Works of Lukas Foss.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2015/02/8620/ ______. April 27, 2011. “Good as Gould.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/04/good-as-gould/ Padua, Pat. July 25, 2012. “Clark Lights Up the Library.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2012/07/clark- lights-up-the-library/ Smigel, Libby. -

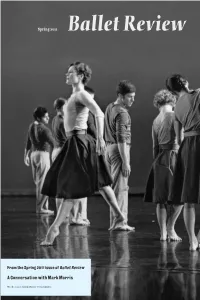

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St.