Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles Blog Posts

More Than Words: Designs, Dance, and Graphic Notation in the Performing Arts Society of American Archivists, August 2021 / Virtual Tour Library of Congress, Music Division Resources Articles Library of Congress Magazine Brilliant Broadway: Volume 7, No. 3, May-June 2018: Christopher Hartten, “Brilliant by Design” Library of Congress Magazine - May/June 2018 (loc.gov) Blog Posts: In the Muse Albro, Sylvia. Undated. “Conservation Treatment of Seven Engraved Music Motets.” https://www.loc.gov/preservation/conservators/musicmotets/index.html Baumgart, Emily. May 29, 2021. “Cicada Terrible Freedom.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/05/cicada-terrible-freedom/ ______. March 11, 2021. "A New LGBTQ+ Resource from the Library of Congress Music Division" https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/03/a-new-lgbtq-resource-from-the-library-of-congress-music- division Doyle, Kaitlin (Kate). July 9, 2016. “Discovering the Music Within Our Dance Collections: Composer Lucia Dlugoszewski and the Erick Hawkins Dance Company.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2016/09/discovering-the-music-within-our-dance-collections- composer-lucia-dlugoszewski-and-the-erick-hawkins-dance-company/ Hartten, Chris. September 6, 2011. “The Bad Boy of Music.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/09/the-bad-boy-of-music/ ______. February 19, 2015. “Chameleon as Composer: The Colorful Life and Works of Lukas Foss.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2015/02/8620/ ______. April 27, 2011. “Good as Gould.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/04/good-as-gould/ Padua, Pat. July 25, 2012. “Clark Lights Up the Library.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2012/07/clark- lights-up-the-library/ Smigel, Libby. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

March 6-7, 2021

Nutcracker2020 March 6-7, 2021 Lincoln Midwest Ballet Company Shari True, Artistic Director Artistic Director Shari True presents The Nutcracker Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Saturday, March 6, 2021 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. & Sunday, March 7, 2021 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. Technical Director: Daniel Anderson, Stratum Productions Stage Manager: Melanie Rudy Assistant Stage Managers: Eric Himmelberger, Kayci Johnston Stage Crew: Jamie Stephens, Paul Watson, Jaylin Wiese Props Coordinator: Tonia O’Hare Head Costumer and Costume Builder: Maralee Maldavs Hair & Makeup Designer & Assistant Costumer: Donna Himmelberger Assistant to the Costumer: Emily Maldavs Lighting Designer: John Himmelberger Sound Technician: Marlan Hohnstein Rehearsal Assistants: Betsy Andersen, Ashley Rutt Executive Director: Kelly Duncan Due to Covid-19 guidelines, we regret that drinking fountains and refreshment booths are not open. Restrooms are available as needed. 3 Lincoln Midwest Ballet Company EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Marcia Kirk, President Debby Erickson, Vice President Kenton Sullivan, President-elect Christine Mann, Vice President Renee Yost, Treasurer Vicki Schulenberg, Vice President Lana Peterson-Pressler, Secretary DIRECTORS Cori Amend Toni Montanez DIRECTORS EMERITI Jim Beitel Joyce Latrom Joan Chopp Angie Muhleisen Michael Dowd J. Michael Rierden Nancy Ingham Susan Steinegger Linda Laird Lyn Wineman LMBC MISSION The Mission of the Lincoln Midwest Ballet Company is to promote excellence in the art of ballet through performances, education, and community outreach. LMBC extends our appreciation to all of the area dance studios. The success of The Nutcracker depends upon your passion for dance and the support and guidance you provide to the talented youth of our community. LMBC thanks the following individuals who gave their time and skills to staff our first aid site: Stacey Bergantzel, RN . -

Julia Erickson to Give Farewell Performance at October Mixed Repertory Program

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Meghan Swartz Associate Director of Communications 412-454-9117 [email protected] High-res photos available upon request. Principal Ballerina to Close 17-year Career with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Julia Erickson to Give Farewell Performance at October Mixed Repertory Program PITTSBURGH, PA (Feb. 1, 2018) - Julia Erickson, one of Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre’s (PBT) longest-tenured principal dancers, has announced her plans to close her 17-year career with PBT following the company’s 2018-2019 Season opener in October. This season, fans can still look forward to seeing Erickson dance one of her signature roles, Odette/Odile, in PBT’s production of “Swan Lake,” on stage Feb. 16-25, at the Benedum Center. Erickson will star as Odette/Odile, commonly known as White Swan/Black Swan, in the 8 p.m. Friday, Feb. 23, performance. She also is premiering original choreography in the “PBT: New Works” program, March 16-25, at the August Wilson Center, and preparing for the lead singing role of Anita in “West Side Story Suite,” part of PBT’s May 4-6, Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein celebration presented by UPMC. The date of her fall farewell performance will be announced in early October. "I have treasured my time at Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre. The rich and rewarding personal and professional relationships I have developed will be with me forever. In this spirit I will relish my last months here with the company in the rehearsal studio and on the Benedum Center stage more than ever,” Erickson said. “As bittersweet as my departure is, I will remain connected to all of the people in the community who mean so much to me as I branch out and engage in new opportunities. -

Commence to Dancing by David Vaughan Introduced by Alastair Macaulay

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Commence to Dancing By David Vaughan Introduced by Alastair Macaulay THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS Commence to Dancing The Senior CriTics AwArd, delivered By David VaughAn at The DanCe CriTics AssoCiation at DanCe new AmsterdAm, new york CiTy, on 17 June 2007 Introduction by Alastair Macaulay This is the Dance Critics’ Association; and I hope that many of you here first got to know David the way I did—by reading him in print. In 1965, he was a founding figure at Ballet Review and, alone of that magazine’s founders, he still contributes regularly to it. In fact, its “Annals of The Sleeping Beauty” department would scarcely exist without him. For many years, he was the Financial Times’s distinguished New York dance correspondent. His book Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years (Aperture, 2005) is indispensable to anyone writing on the subject, and I say that as someone who has sometimes groaned at its sheer weight across my knees. I myself came to know him through his book Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (A & C Black, 1977)—“the Ashton book,” as it was known for many years. For me, this came at an opportune moment: I was twenty-two, and the two Royal Ballet companies staged an unusually large number of Ashton ballets in the year it was published. I had read the book from cover to cover the moment it came out; then I read it again from cover to cover; and then, every time I went to see any Ashton performance, I would read the relevant section both before setting out and then on returning home. -

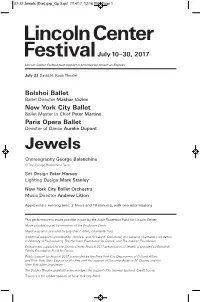

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1

07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 22 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev New York City Ballet Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins Paris Opera Ballet Director of Dance Aurélie Dupont Jewels Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Set Design Peter Harvey Lighting Design Mark Stanley New York City Ballet Orchestra Music Director Andrew Litton Approximate running time: 2 hours and 10 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by members of the Producers Circle Major support is provided by LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support is provided by Jennie L. and Richard K. DeScherer, the Lepercq Charitable Foundation in Memory of Paul Lepercq, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, and The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of Jewels is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. Travelers is the Global Sponsor of New York City Ballet. 07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 JEWELS July 22, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. -

Making an American Dance

Making an American Dance: Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring LYNN GARAFOLA Few American composers had a longer or more intimate association with dance than Aaron Copland. He discovered it as an exciting form of thea ter art in Paris during his student years, which coincided with the heyday of Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and Rolf de Mare's Ballets Suedois. In the Paris of the early 1920s new music and ballet were synonymous. Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Falla were stars of the "Russian" troupe; Satie, Milhaud, and Honegger of the "Swedish" one. In 1923, like so many other young composers, Copland attended the revival of Stravinsky'S Rite of Spring and the first performance of his Les Noces, as well as the premiere of Milhaud's La Creation du Monde. Copland's first orchestral score, which he began in Paris, was a ballet. Although it was never produced, he recy cled parts of it in his 1929 Dance Symphony, an independent orchestral work, and his 1934 ballet for Ruth Page, Hear lef Hear lef. "Ballet was the big thing in Paris during the 1920s," he told Phillip Ramey in 1980. "One of the first things I did upon arriving in Paris in 1921 was to go to the Ballets Suedois, where I saw Milhaud's £Homme et son Desir."] Copland discovered ballet in the aftermath ofDiaghilev's modernist revo lution. Through his successive choreographers-Michel Fokine and Vaslav Nijinsky before World War I, Uonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska, and George Balanchine during and after the war-Diaghilev transformed not only what ballet looked lil(e but also how it sounded. -

LGBTQ+ Artists Represented Int the Performing Arts Special Collections

LGBTQ+ Artists Represented in the Performing Arts Special Collections in the Library of Congress Music Division Aaron Copland with Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti, 1945 (Aaron Copland Collection, Box 479 Folder 3) Compiled by Emily Baumgart Archives Processing Technician January 2021 Introduction The artistic community has always had many LGBTQ+ members, including musicians, dancers, choreographers, writers, directors, designers, and other creators. The Music Division holds a wealth of information about these LGBTQ+ artists in its performing arts special collections, which contain musical scores, correspondence, scripts, photographs and other documents of their lives and careers. This survey brings together some of the highlights from these holdings, providing an opportunity to learn more about LGBTQ+ creators and to recognize and celebrate their artistic achievements. The sexual and gender identity of many historical figures has been obscured over time; moreover, it can be difficult to determine how such individuals would identify by today’s terminology, especially when little of their personal life is known. Other figures, however, have disclosed their identity through their private correspondence or other writings. We do not wish to ascribe to any person an identity that they may have disagreed with, but at the same time we recognize that many of the queer community’s accomplishments have been hidden through oppression, prejudice, and forced closeting. By increasing awareness of LGBTQ+ identity in the Music Division’s special collections, we can make relevant primary source materials more readily accessible for students, educators, and scholars to study these creators and their contributions. This survey does not claim to be comprehensive, neither in terms of identifying every LGBTQ+ artist within the Music Division’s special collections nor in terms of identifying every collection in which those artists are represented. -

Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976) Humanities, Subject Files II (1962-1996)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Education: National Endowment for the Arts and Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976) Humanities, Subject Files II (1962-1996) 1966 Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976): Report 13 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/pell_neh_II_5 Recommended Citation "Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976): Report 13" (1966). Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976). Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/pell_neh_II_5/1 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Education: National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities, Subject Files II (1962-1996) at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts and Humanities: Appropriations (1976) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I I I I NATIONAL ENDOWMENT· I FOR THE ARTS I and NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS I I I ·1 I I I I I I I I I I I I Letter of Tta:nsinittal I W{!.sh:i!lgt:c)!i., D. C• I January 15, 1967 My f>eat Mr. President: I l h~ve the ho~or to sybJ!lit herewith the annual r~port of the National Endowme11t fo-r t}ie Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the I fiscal yea~ eµd:f.11g J\1:q~ .30, 1966. I ~'h~ I Roger Stevens, Ch~:f.~!l National Endowment fo~ th~ ~~ts I The Honorable I The President of the United Stat~s I I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I The Chairman's State_meil,t ...••.••..•..••....••••.•••.••..•.•..•.•..•..... -

Cast Biographies

CAST BIOGRAPHIES BEN DANIELS (Paul Grayson) Ben Daniels is known for his impressive work in theatre, television and film. Daniels can most recently be seen on the small screen in “Jamaica Inn” (BBC), “The Paradise” (BBC) “Law and Order: UK,” the Netflix Original Series “House of Cards” alongside Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, and Buckingham in The Hollow Crown, Richard III alongside Bendedict Cumberbatch. On the big screen he can most recently be seen in the films Luna, as the voice of Gareth in Locke alongside Tom Hardy. Previous film credits include Jack the Giant Slayer (Warner Bros.) Wipers Times, Doom (Universal Studios), Married Unmarried, Fanny and Elvis, Madeleine (Sony), I Want You, Passion in the Desert (New Line), and Beautiful Thing (Channel 4 Films). Previous television credits include, “Merlin,” “Women in Love,” “The Last Days of Lehman Brothers,” “The Passion,” “Lark Rise To Candleford ,” “Who Killed Mrs. De Ropp,” “The State Within,” “Ian Fleming: Bondmaker,” “Elizabeth – The Virgin Queen,” “MI-5,” “Miss Marple: What Mrs. Mcgillicuddy Saw,” “Real Men,” “Cutting It,” “Conspiracy,” “Aristocrats” “Silent Witness,” “Britannic,” “David,” “Outside Edge,” “Inspector Alleyn Mysteries: Death At The Bar,” “Truth Or Dare,” “Romeo And Juliet,” and “The Lost Language Of Cranes.” On stage, Daniels last starred in the Broadway revival of “Don’t Dress For Dinner” in 2012. Prior to this he appeared in “Haunted Child” and “Luise Miller” in 2011. He first starred on Broadway in “Les Liaisons Dangereuses » in 2008 for which he earned a Tony Award nomination for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play and was the winner of a TWA award for Outstanding Broadway Debut. -

Kathryn Morgan Maria Riccetto Craig Hall Adrian Danchig-Waring Cory Stearns

AtheneumDanceFestCovers10:AtheneumDanceFestivalCovers10 7/15/10 4:36 PM Page 1 NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTI VAL July 26 –31, 2 01 0 Friday, July 30th, 6:30 P.M. Saturday, July 31st, 6:30 P.M. Nantucket High School Mary P. Walker Auditorium 1 AtheneumDanceFestCovers10:AtheneumDanceFestivalCovers10 7/15/10 4:36 PM Page 2 DANCE FESTIVAL COMMITTEE 2010 Marion Martin Jane Tyler Marcia P. Welch Dance Festival Co-Chairs Mary Randolph Ballinger Cosby George A. Steven Perelman Susie Belcher Tim George Samantha Sandler Roxanne Casscells Nan Geschke Denise Saul Barbara G. Cohen Molly Harding Maria Spears Patti Deuster Kathryn Kay Pam Thomas Barbara J. Fife John W. Loose Mary Wolff Alan Forster Mary Ann Peglar NANTUCKET ATHENEUM BOARD OF TRUSTEES Alice F. Emerson Stephen C. Anderson Chair Vice-Chair Judith Tindal Opatrny Alan Forster Secretary Treasurer Margaret Gaffney Benedict Timothy M. George Donald M. Stewart Susan Boardman Elizabeth Grubbs Bernard L. Swain William J. Charlton Kathryn Kay Jane Tyler Tharon Dunn Jeanne Casey Miller Marcia P. Welch Douglass N. Ellis A. Steven Perelman Jay M. Wilson Barbara J. Fife Anne Phaneuf Ronald Winters William G. Spears Chairman Emeritus Trustees Emeriti John W. Loose Nan Geschke Martha Groetzinger Executive Director President Emeritus Nancy A. Newhouse Molly C. Anderson Robert F. Mooney Honorary Trustees Mr. and Mrs. Robert Diamond Jr. Lucile W. Hays Mr. and Mrs. Richard Menschel Richard M. Scaife Margaret B. Scaife 2 AtheneumDanceFestCovers10:AtheneumDanceFestivalCovers10 7/15/10 4:36 PM Page 3 NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTI VAL 201 0 Featuring stars of American Ballet Theatre and The New York City Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Gillian Murphy Teresa Reichlen Jennie Somogyi Wendy Whelan Tyler Angle Gonzalo Garcia David Hallberg Benjamin Millepied Jonathan Stafford Kathryn Morgan Maria Riccetto Craig Hall Adrian Danchig-Waring Cory Stearns Amanda Hankes Blaine Hoven Pianist: Cameron Grant Cellist: Ann Kim Nantucket High School Auditorium Friday, July 30, 2010 at 6:30 p.m.