Notes and Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh

gendered embodiments: mapping the body-politic of the raped woman and the nation in Bangladesh Mookherjee, Nayanika . Feminist Review, suppl. War 88 (Apr 2008): 36-53. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers Turn off hit highlighting Other formats: Citation/Abstract Full text - PDF (206 KB) Abstract (summary) Translate There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation. Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts. This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. I show the ways in which the visual representation of this 'motherland' as fertile countryside, and its idealization primarily through rural landscapes has enabled a crystallization of essentialist gender roles for women. This article is particularly interested in how these images had to be reconciled with the subjectivities of women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War (Muktijuddho) and the role of the aestheticizing sensibilities of Bangladesh's middle class in that process. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT] Show less Full Text Translate Turn on search term navigation introduction There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation (Yuval-Davis and Anthias, 1989; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis and Werbner, 1999). Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts (Kandiyoti, 1991; Chatterjee, 1994). This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. -

Folk Hinduism in West Bengal

1 Folk Hinduism in West Bengal In the rural areas of India, we see a variety of notions about the nature of gods and goddesses. They are not “high gods,” as we see in the pan-Indian brahmanical forms of Hinduism, but rather regional deities, intimately associated with villages and towns. Indeed, some would not be characterized as gods and goddesses by most people, for those supernatural entities given offerings and worship include ghosts, ancestors, water and plant essences, guardian spirits, and disease con- trollers. We see some overlap of tribal deities, the deities of non-Hindu or semi- Hindu villagers, with the village gods or gramadevatas of village Hinduism. These may be µeld or mountain spirits, or angry ghosts of women who died violent deaths. All of these may be seen in the large area of folk Hinduism. There is no sharp differentiation between the tribal deities, village deities, and gods and god- desses of brahmanical Hinduism. Rather than a polarity, we see a continuum, for these traditions worship many deities in common. Some themes that may be noted in the worship of folk gods and goddesses: Regionalism: These deities are associated with speciµc places, temples, µelds, and streams. The Kali of one village is not the same as the next village’s Kali. One Chandi gives good hunting, another Chandi cures disease. Goddesses are not pan-Indian; they are speciµc to a person’s tribal or caste group, ex- tended family, neighborhood, or village. Pragmatism: These deities are rarely worshiped in a spirit of pure and ab- stract devotion. -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

Devotional Practices (Part -1)

Devotional Practices (Part -1) Hare Krishna Sunday School International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acarya : His Divine Grace AC. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Price : $4 Name _ Class _ Devotional Practices ( Part - 1) Compiled By : Tapasvini devi dasi Vasantaranjani devi dasi Vishnu das Art Work By: Mahahari das & Jay Baldeva das Hare Krishna Sunday School , , ,-:: . :', . • '> ,'';- ',' "j",.v'. "'.~~ " ""'... ,. A." \'" , ."" ~ .. This book is dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder acarya ofthe Hare Krishna Movement. He taught /IS how to perform pure devotional service unto the lotus feet of Sri Sri Radha & Krishna. Contents Lesson Page No. l. Chanting Hare Krishna 1 2. Wearing Tilak 13 3. Vaisnava Dress and Appearance 28 4. Deity Worship 32 5. Offering Arati 41 6. Offering Obeisances 46 Lesson 1 Chanting Hare Krishna A. Introduction Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu, an incarnation ofKrishna who appeared 500 years ago, taught the easiest method for self-realization - chanting the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra. Hare Krishna Hare Krishna '. Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rams Rams Rama Hare Hare if' ,. These sixteen words make up the Maha-mantra. Maha means "great." Mantra means "a sound vibration that relieves the mind of all anxieties". We chant this mantra every day, but why? B. Chanting is the recommended process for this age. As you know, there are four different ages: Satya-yuga, Treta-yuga, Dvapara-yuga and Kali-yuga. People in Satya yuga lived for almost 100,000 years whereas in Kali-yuga they live for 100 years at best. In each age there is a different process for self realization or understanding God . -

Tagore's Song Offerings: a Study on Beauty and Eternity

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Tagore’s Song Offerings: A Study on Beauty and Eternity Dr. Tinni Dutta Lecturer, Department of Psychology , Asutosh College Kolkata , India. ABSTRACT Gitanjali written by Rabindranath Tagore (and the English translation of the Corresponding Author: Bengali poems in it, written in 1921) was awarded the Novel Prize in 1913. He Dr. Tinni Dutta called it Song Offerings. Some of the songs were taken from „Naivedya‟, „Kheya‟, „Gitimalya‟ and other selections of his poem. That is, the Supreme Being is complete only together with the soul of the devetee. He makes the mere mortal infinite and chooses to do so for His own sake, this could be just could be a faint echo of the AdvaitaPhilosophy.Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali express the distinctive method of philosophy…The poet is nothing more than a flute (merely a reed) which plays His timeless melodies . His heart overflows with happiness at His touch that is intangible Tagore‟s song in Gitanjali are analyzed in this ways - content analysis and dynamic analysis. Methodology of his present study were corroborated with earlier findings: Halder (1918), Basu (1988), Sanyal (1992) Dutta (2002).In conclusion it could be stated that Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali are intermingled with beauty and eternity.A frequently used theme in Tagore‟s poetry, is repeated in the song,„Tumiaamaydekechhilechhutir‟„When the day of fulfillment came I knew nothing for I was absent –minded‟, He mourns the loss. This strain of thinking is found also in an exquisite poem written in old age. -

Postcolonial Resistance of India's Cultural Nationalism in Select Films

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 25 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies ISSN: 2456-7507 <postscriptum.co.in> Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed Volume V Number i (January 2020) Postcolonial Resistance of India’s Cultural Nationalism in Select Films of Rituparno Ghosh Koushik Mondal Research Scholar, Department of English, Visva Bharati Koushik Mondal is presently working as a Ph. D. Scholar on the Films of Rituparno Ghosh. His area of interest includes Gender and Queer Studies, Nationalism, Postcolonialism, Postmodernism and Film Studies. He has already published some articles in prestigious national and international journals. Abstract The paper would focus on the cultural nationalism that the Indians gave birth to in response to the British colonialism and Ghosh’s critique of such a parochial nationalism. The paper seeks to expose the irony of India’s cultural nationalism which is based on the phallogocentric principle informed by the Western Enlightenment logic. It will be shown how the idea of a modern India was in fact guided by the heteronormative logic of the British masters. India’s postcolonial politics was necessarily patriarchal and hence its nationalist agenda was deeply gendered. Exposing the marginalised status of the gendered and sexual subalterns in India’s grand narrative of nationalism, Ghosh questions the compatible comradeship of the “imagined communities”. Keywords Hinduism, postcolonial, nationalism, hypermasculinity, heteronormative postscriptum.co.in Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed ISSN 24567507 5.i January 20 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 26 India‟s cultural nationalism was a response to British colonialism. The celebration of masculine virility in India‟s cultural nationalism roots back to the colonial encounter. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

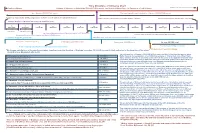

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

HINDU GODS and GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA the First Deity of The

HINDU GODS AND GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA The first deity of the Hindu trinity, Lord Brahma is considered to be the god of Creation, including the cosmos and all of its beings. Brahma also symbolizes the mind and intellect since he is the source of all knowledge necessary for the universe. Typically you’ll find Brahma depicted with four faces, which symbolize the completeness of his knowledge, as well as four hands that each represent an aspect of the human personality (mind, intellect, ego and consciousness). 2. VISHNU The second deity of the Hindu trinity, Vishnu is the Preserver (of life). He is believed to sustain life through his adherence to principle, order, righteousness and truth. He also encourages his devotees to show kindness and compassion to all creatures. Vishnu is typically depicted with four arms to represent his omnipotence and omnipresence. It is also common to see Vishnu seated upon a coiled snake, symbolizing the ability to remain at peace in the face of fear or worry. 3. SHIVA The final deity of the Hindu trinity is Shiva, also known as the Destroyer. He is said to protect his followers from greed, lust and anger, as well as the illusion and ignorance that stand in the way of divine enlightenment. However, he is also considered to be responsible for death, destroying in order to bring rebirth and new life. Shiva is often depicted with a serpent around his neck, which represents Kundalini, or life energy. 4. GANESHA One of the most prevalent and best-known deities is Ganesha, easily recognized by his elephant head. -

Glimpses from the North-East.Pdf

ses imp Gl e North-East m th fro 2009 National Knowledge Commission Glimpses from the North-East National Knowledge Commission 2009 © National Knowledge Commission, 2009 Cover photo credit: Don Bosco Centre for Indigenous Cultures (DBCIC), Shillong, Meghalaya Copy editing, design and printing: New Concept Information Systems Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] Table of Contents Preface v Oral Narratives and Myth - Mamang Dai 1 A Walk through the Sacred Forests of Meghalaya - Desmond Kharmawphlang 9 Ariju: The Traditional Seat of Learning in Ao Society - Monalisa Changkija 16 Meanderings in Assam - Pradip Acharya 25 Manipur: Women’s World? - Tayenjam Bijoykumar Singh 29 Tlawmngaihna: Uniquely Mizo - Margaret Ch. Zama 36 Cultural Spaces: North-East Tradition on Display - Fr. Joseph Puthenpurakal, DBCIC, Shillong 45 Meghalaya’s Underground Treasures - B.D. Kharpran Daly 49 Tripura: A Composite Culture - Saroj Chaudhury 55 Annexure I: Excerpts on the North-East from 11th Five Year Plan 62 Annexure II: About the Authors 74 Preface The north-eastern region of India is a rich tapestry of culture and nature. Breathtaking flora and fauna, heritage drawn from the ages and the presence of a large number of diverse groups makes this place a treasure grove. If culture represents the entire gamut of relationships which human beings share with themselves as well as with nature, the built environment, folk life and artistic activity, the north-east is a ‘cultural and biodiversity hotspot’, whose immense potential is beginning to be recognised. There is need for greater awareness and sensitisation here, especially among the young. In this respect, the National Knowledge Commission believes that the task of connecting with the north-east requires a multi-pronged approach, where socio-economic development must accompany multi-cultural understanding. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Syllabus for Bcs (Written) Examination 1/210 সূচিপত্র

SYLLABUS FOR BCS (WRITTEN) EXAMINATION সবয়শষব হোলনোগোদ: ২৩.০৮.২০২১ চিপত্র [Contents] (ক) আবচিক চবষয়স맂হ [Compulsory Subjects] ক্র: চবষয় ককোড চবষয়য়র নোম ꧃ষ্ঠোন ম্বর নং [Subject Code] [Subject Name] 1. 001 বাাংলা১ ম পত্র [Bangla 1st Paper] ৪ 2. 002 বাাংলা২ য় পত্র [Bangla 2nd Paper] ৪ 3. 003 ইাংরেজি [English] ৫ 4. 005 বাাংলারেশ জবষয়াবজল [Bangladesh Affairs] ৬-৭ 5. 007 আিাজ জিক জবষয়াবজল [International Affairs] ৮-৯ 6. 008 গাজিজিক 뷁জি [Mathematical Reasoning] ১০ 7. 009 মানজিক েিা [Mental Ability] ১১-১২ 8. 010 িাধােি জবজ্ঞান ও প্র뷁জি [General Science and Technology] ১৩-১৫ (খ) পদ-সংচিষ্ট চবষয়স맂হ [Post Related Subjects] [�鷁 কোচরগচর/য়পশোগত কযোডোয়রর জন্য (For Professional/Technical Cadre Only)] ক্র: চবষয় ককোড চবষয়য়র নোম ꧃ষ্ঠা নম্বর নং [Subject Code] [Subject Name] 1. 111 বাাংলা ভাষা ও িাজিিয [Bangla Language and Literature] ১৬ 2. 121 ইাংরেজি [English] ১৭ 3. 131 আেজব [Arabic] ১৮ 4. 141 ফোসী [Persian] ১৯ 5. 151 িাংস্কৃি [Sanskrit] ২০ 6. 161 পাজল [Pali ২১ 7. 171 মরনাজবজ্ঞান [Psychology] ২২-২৩ 8. 181 ইজিিাি [History] ২৪-২৫ 9. 191 ইিলারমে ইজিিাি ও িাংস্কৃজি [Islamic History & Culture] 26-27 10. 201 ইিলামী জশা [Islamic Studies] 28-29 11. 211 েশনজ [Philosophy] 30-31 12. 221 জশা [Education] 32-33 13. 231 প্রত্নিত্ত্ব [Archaeology] 34-36 14.