Schopenhauer's Use of Odd Phenomena to Corroborate His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paolo Stellino

Philosophical Perspectives on Suicide Paolo Stellino Philosophical Perspectives on Suicide Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Wittgenstein Paolo Stellino Nova Institute of Philosophy Universidade Nova de Lisboa LISBOA, Portugal ISBN 978-3-030-53936-8 ISBN 978-3-030-53937-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53937-5 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 Tis work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Te use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Te publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Te publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations. Tis Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG. -

The Affirmation of the Will

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62695-9 - Schopenhauer: A Biography David E. Cartwright Excerpt More information 1 The Affirmation of the Will RTHUR SCHOPENHAUER VIEWED himself as homeless. This sense of A homelessness became the leitmotif of both his life and his philos- ophy. After the first five years of his life in Danzig, where he was born on 22 February 1788, his family fled the then free city to avoid Prus- sian control. From that point on, he said, “I have never acquired a new home.”1 He lived in Hamburg on and off for fourteen years, but he had his best times when he was away from that city. When he left Hamburg, he felt as if he were escaping a prison. He lived for four years in Dresden, but he would only view this city as the birthplace of his principal work, The World as Will and Representation. More than a decade in Berlin did nothing to give him a sense of belonging. He would angrily exclaim that he was no Berliner. After living as a noncitizen resident in Frankfurt am Main for the last twenty-eight years of his life, and after spending fifty years attempting to understand the nature and meaning of the world, he would ultimately conclude that the world itself was not his home. If one were to take this remark seriously, then even Danzig had not been his home. He was homeless from birth. But being homeless from birth did not mean that there was no point to his life. Schopenhauer would also conclude that from birth he had a mission in life. -

On Faith-Healing New Secular Humanist Centers?

New Secular More on Humanist Faith-Healing Centers? James Randi Paul Kurtz Gerald Larue Vern Bullough Henry Gordon Bob Wisne David Alexander Faith-healer Robert Roberts Also: Is Goldilocks Dangerous? • Pornography • The Supreme Court • Southern Baptists • Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in France 1n Its Tree _I FALL 1986, VOL. 6, NO. 4 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 17 BIBLICAL SCORECARD 62 CLASSIFIED 12 ON THE BARRICADES 60 IN THE NAME OF GOD 6 EDITORIALS Is Goldilocks Dangerous? Paul Kurtz / Pornography, Censorship, and Freedom, Paul Kurtz I Reagan's Judiciary, Ronald A. Lindsay / Is Secularism Neutral? Richard J. Burke / Southern Baptists Betray Heritage, Robert S. Alley / The Holy-Rolling of America, Frank Johnson 14 HUMANIST CENTERS New Secular Humanist Centers, Paul Kurtz / The Need for Friendship Centers, Vern L. Bullough / Toward New Humanist Organizations, Bob Wisne THE EVIDENCE AGAINST REINCARNATION 18 Are Past-Life Regressions Evidence for Reincarnation? Melvin Harris 24 The Case Against Reincarnation (Part 1) Paul Edwards BELIEF AND UNBELIEF WORLDWIDE 35 Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in Present-Day France Jean Boussinesq MORE ON FAITH-HEALING 46 CS ER's Investigation Gerald A. Larue 46 An Answer to Peter Popoff James Randi 48 Popoff's TV Empire Declines .. David Alexander 49 Richard Roberts's Healing Crusade Henry Gordon IS SECULAR HUMANISM A RELIGION? 52 A Response to My Critics Paul Beattie 53 Diminishing Returns Joseph Fletcher 54 On Definition-Mongering Paul Kurtz BOOKS 55 The Other World of Shirley MacLaine Ring Lardner, Jr. 57 Saintly Starvation Bonnie Bullough VIEWPOINTS 58 Papal Pronouncements Delos B. McKown 59 Yahweh: A Morally Retarded God William Harwood Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Doris Doyle, Steven L. -

Animal Magnetism - U Nlllasked

Animlal Magnetism - Unmasked Max Kappeler Animal Magnetism - U nlllasked Max Kappeler An analysis of the chapter "Animal Magnetism Unmasked" in the Christian Science textbook Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy Kappeler Institute Publishing PO Box 99735, Seattle, WA 98139-0735 Translated from the original German, Tierischer Magnetismus-entlarvt (Zurich 1974) by Kathleen Lee © 1975 Max Kappeler © 2004 Kappeler Institute, second edition All rights reserved ISBN: 0-85241-097-2 Cover by: Blueline Design Seattle, WA Kappeler Institute Publishing, USA PO Box 99735, Seattle, WA 98139-0735 Tel: (206) 286-1617 • FAX: (206) 286-1675 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kappelerinstitute.org Abbreviations used to reference the works by and about Mary Baker Eddy S&H Throughout this book, quotations from the Chris tian Science textbook, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, will be noted with only a page and line number, for example: (254:19). Quotations that occur in this form will always be referencing the 1910 Textbook. ColI. Course in Divinity and General Collectanea, pub lished by Richard F. Oakes, London, 1958 (also known as the "blue book") Journal The Christian Science Journal Mis. Miscellaneous Writings My. The First Church o/Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany Ret. Retrospection and Introspection Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1: The History of Animal Magnetism ........................ 4 Franz Anton Mesmer -

Issue-05-9.Pdf

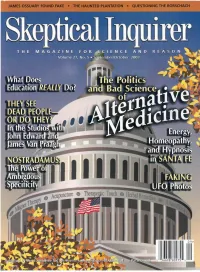

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist. -

Chiropractic History: a Primer

PracticeMakers_504474 3/21/05 3:35 AM Page 1 Chiropractic History: a Primer Joseph C. Keating, Jr., Ph.D. Secretary & Historian, National Institute of Chiropractic Research Director, Association for the History of Chiropractic Carl S. Cleveland III, D.C. President, Cleveland Chiropractic Colleges Director, Association for the History of Chiropractic Michael Menke, M.A., D.C. Faculty Member, National University of Health Sciences Faculty Member, University of Arizona 1 PracticeMakers_504474 3/21/05 3:35 AM Page 2 The NCMIC Insurance Company is proud to make this primer of chiropractic history possible through a grant to the Association for the History of Chiropractic. NCMIC recognizes the importance of preserving the rich history of our profession. This primer will hopefully stimulate your interest in this saga, help you to understand the trials and tribula- tions our pioneers endured, and give you a sense of pride and identity. Lee Iacocca, in his book about LIBERTY said: I know that liberty brings with it some obligations. I know we have it today because others fought for it, nourished it, protected it, and then passed it on to us. That is a debt we owe. We owe it to our parents, if they are alive, and to their memory if they are not. But mostly we have an obligation to our own kids. An obligation to pass on this incredible gift to them. This is how civilization works... whatever debt you owe to those who came before you, you pay to those who follow. That is essentially the same responsibility each of us has to preserve and protect the extraordinary history of this great profession. -

Stanley Krippner's CV

BIBLIOGRAPHY, Stanley Krippner AUDIO/VIDEO RECORDINGS Fischer, S., & Krippner, S. (2004). How to cope with stress (DVD). New York: Dorot Lecture Series Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1991). Personal mythology: How to use ritual, dreams, and imagination to discover your inner story (Cassette Recording #1-55927-136-1). Los Angeles: Audio Renaissance Tapes. Krippner, S. (1989). Understanding your dreams (Cassette Recording #PSG-2002). New Rochelle, NY: Great American Audio. BOOKS AUTHORED OR CO-AUTHORED Elliot, P., Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1986). Rituals for living and dying. Ashland, OR: Innersource. Elliot, P., Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1987). Rituals for living and dying (rev. ed.). Ashland, OR: Innersource. Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1988). Personal mythology: The psychology of your evolving self. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher. Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1989). Personal mythology: The psychology of your evolving self. London: Unwin Hyman. Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1989). Personal mythology: The psychology of your evolving self. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher. (paperback edition) Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1997). The mythic path. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam. Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (2006). The mythic path (3rd ed.). Santa Rosa, CA: Elite Press. Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (2008). Personal mythology: Using ritual, dreams, and imagination to discover your inner story (3rd ed.). Santa Rosa, CA: Energy Psychology Press/Elite Books. Iljas, J., & Krippner, S. (2016). Sex and love in the Bay: An introduction to sexology for young people. San Rafael, CA: Iljas-Angel Publications. Iljas, J., & Krippner, S. (2017). Sex and love in the 21st century: An introduction to sexology for young people. Austin, TX: Sentia Publishing. -

Magic, Witchcraft, Animal Magnetism, Hypnotism and Electro-Biology

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com |G-NRLF ||||I|| * * B 51D * - 5 B E R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA This is an authorized facsimile of the original book, and was produced in 1975 by microfilm-xerography by Xerox University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. ♦ .MAGIC, WITCHCRAFT, ANIMAL MAGNETISM, HYPNOTISM, AND ELECTEO-BIOLOGT; BEING A DIGEST OF THE LATEST VIEWS OP THE AUTHOR ON THESE SUBJECTS. / JAMES BRAID, M.R.C.S. Emh., C.M.W.S., Ac. y, THIRD EDITION^ GREATLY ENLARGED, lL ~> XHBUCIXO OBSIETIIIOIH OH J. C. COLQUHOUN'S "HISTOBY OF MAGIC," Ao. 'uacoi run, amicus iocutu, iid mioii ahica niiru." LONDON: JOHN CHUBCHILL, PEINCES 8TBBET, SOHO. ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, EDINBURGH. 1852. BFII3/ & 7 30 ft*. "SO MEN OF I1HJEPENDENT HABITS OF THOUOIIT CAJf BE DRIVES WTO BELIEF: THEIR BEASOX MUST BE AITEALED TO, ASD T1IEIR objections CALMLY vet." — Brit, and For. Hcd.'Chir. Sevica. PREFACE. In the first edition of these " Observations," I merely intended to shield myself against the more important points upon which I considered Mr. Colquhoun had misrepresented me. In the second edition I went more into detail, and quoted additional authorities in support of my theory of the nature, cause., and extent of hypnotic or mesmeric phenomena. In the third edition I have gone so much more into detail, as to furnish a periscope or vidimus of my views on all the moro important points of the hypnotic and mesmeric speculations. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87185-3 - Arthur Schopenhauer: Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays: Volume 2 Edited by Adrian Del Caro and Christopher Janaway Frontmatter More information ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER Parerga and Paralipomena The purpose of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Schopenhauer is to offer translations of the best modern German editions of Schopenhauer’s work in a uniform format suitable for Schopenhauer scholars, together with philosophical introductions and full editorial apparatus. With the publication of Parerga and Paralipomena in 1851, there finally came some measure of the fame that Schopenhauer thought was his due. Described by Schopenhauer himself as ‘incomparably more popular than everything up till now’, Parerga is a miscellany of essays addressing themes that complement his work The World as Will and Representation, along with more divergent, speculative pieces. It includes essays on method, logic, the intellect, Kant, pantheism, natural science, religion, education, and language. The present volume offers a new translation, a substantial introduction explaining the context of the essays, and extensive editorial notes on the different published versions of the work. This readable and scholarly edition will be an essential reference for those studying Schopenhauer, history of philosophy, and nineteenth-century German philosophy. adrian del caro is Distinguished Professor of Humanities and Head of Modern Foreign Languages and Literatures at the University of Tennessee. He has published many books, including The Early Poetry of Paul Celan: In the beginning was the word (1997) and Grounding the Nietzsche Rhetoric of Earth (2004). He has published numerous articles in journals including Journal of the History of Ideas, Philosophy and Literature, and German Studies Review. -

NASS MONOGRAPH #15 (2011) on the Specter of Speciesism in Spinoza

North American Spinoza Society NASS MONOGRAPH #15 (2011) On the Specter of Speciesism in Spinoza Michael Strawser University of Central Florida Copyright 2011, North American Spinoza Society San Diego, California North American Spinoza Society (NASS) The North American Spinoza Society (NASS), an organization of professional philosophers, philosophy students, and others interested in Spinoza, aims to foster and to promote the study of Spinoza’s philosophy, both in its historical context and in relation to issues of contemporary concern in all areas of research, and to foster communications among North American philosophers and other Spinozists world-wide through other national Spinoza societies. NASS fosters the study of Spinoza through the publication of the NASS Newsletter, org anization of regional meetings in association with meetings of the American Philosophical Association, and circulation of working research papers related to Spinoza and/or Spinozism. The NASS Monograph Series is an occasional one, offering papers selected by the NASS Board. Official languages of NASS are English, French, and Spanish: communications from members and publications may be in any of these. Membership in NASS is open to all who are in agreement with its purposes. Dues are $10.00 per year for regular memberships. Student membership dues are $5.00 per year. Membership for retired or unemployed academics is $5.00 per year. 20% of all membership income is allocated for support of Studia Spinozana. Members receive the NASS Newsletter, NASS Monograph for their membership year, and program papers. NASS Monographs: Purchase Prices Domestic (USA): 3.00 USD postpaid via third class. Foreign (all others): 5.00 USD postpaid via airmail. -

Apport (Paranormal)

Apport (paranormal) 2020-07-03 BFOI Limited anser sig ha en vetenskaplig förklaring på det paranormala problemet med apporter. Vi kommer inte att här gå in på hur denna vetenskapliga förklaring ser ut, men om den föreslagna lösningen är korrekt kommer det att få stora konsekvenser för: 1) relationen mellan det paranormala och det vetenskapliga. 2) frågan om apporter är möjliga att automatisera. Bild ovan/Picture above: Lajos Pap (i mitten/middle), bedrägligt apportmedium/fraudulent apport medium. BFOI Limited arbetar för närvarande nästan uteslutande med denna fråga. Vad vi kunnat konstatera är att apporter är möjliga. Vi har likaså kunnat konstatera att även om apporter kan tyckas vara slumpmässiga är detta inte fallet. Den fråga som nu är av intresse är därför om apporterna är möjliga att styra på något sätt. Nedan återfinns på engelska, som bakgrund till problemet med apporter, vad Wikipedia har att säga om dessa paranormala förflyttningar. In English BFOI Limited considers itself to have a scientific explanation for the paranormal problem of apports. Here we will not go into what this scientific explanation looks like, but if the proposed solution is correct it will have major consequences for: 1) the relationship between the paranormal and the scientific. 2) the issue if apports are possible to automate. BFOI Limited is currently working almost exclusively on this issue. What we have been able to conclude is that apports are possible. We have also been able to conclude that, although apports may appear to be random, this is not the case. The question that is now of interest is therefore whether the apports are possible to control in any way. -

Christian Science

Christian Science An Evaluation from the Theological Perspective of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod April 2005 (updated May 2014) History, Beliefs, Practices Identity: A religious body that may be classified as one of the Mind Science groups (others include the Unity School of Christianity, Religious Science, New Thought, aspects of the New Age movement, and others). Founders: Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910); Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802-1866) Statistics: The bylaws of the church prohibit publishing statistics. The church reports that there are about 2000 churches in 80 countries worldwide.1 As an organization, Christian Science has experienced a sharp decline in members over the past 30 years.2 History: Mary Baker (Eddy), the founder of Christian Science, was born in Bow, New Hampshire, in 1821. Raised as a conservative Congregationalist, she joined a Congregational Church in Tilton, NH, in 1838. However, she was never content with its doctrines, especially the Calvinist doctrine of “double predestination.” Plagued by illnesses throughout most of her life, Eddy acquired a passionate interest in medicine and healing. In 1862 she met Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, whose treatments, Eddy claimed, healed her of a spinal inflammation. It was Quimby who actually developed the religious thought behind Christian Science and the “mind sciences.” He had been studying “animal magnetism” and “mesmerism.” Animal magnetism was a theory advanced by Friedrich Anton Mesmer (1733-1815) according to which an unseen magnetic force is said to surround a person and when “transferred” properly, has the ability to heal people (his ideas concerning the magnetic field and hypnotism came to be known as “Mesmerism”).