Shoes by Steven Paul Lansky I Rushed Through the House, My Face

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 Oslo, Norway

Tel : +47 22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web :www.reisebazaar.no Karl Johans gt. 23, 0159 Oslo, Norway Cycle Cuba: West Turkode Destinasjoner Turen starter QBXC Cuba Havana Turen destinasjon Reisen er levert av 7 dager Havana Fra : NOK 11 097 Oversikt Want to know how it feels to ride alongside tractors and vintage cars, past tobacco farms and the smell of cigars, to have the Caribbean wind whip through your (helmet-covered) hair on a two-wheeled journey through the rich history and crumbling ruins of Old Havana? Find out, on this small group cycling adventure through Cuba’s west. Experience Cuban culture from handle-bar height as you take a leisurely peddle through the capital’s colourful streets, cycle to the pristine shores of Cayo Jutias to cool-off from the heat, and end a rewarding day in the saddle in Vinales with a farm-to- plate feast. From the flora and fauna-filled valleys of Saroa to the welcoming arms of renowned farmer Mama Luisa, take a ‘brake’ from the beaten path and access unique parts of the island that you can only reach on a trusty bicycle. Reiserute Havana Bienvenido a Cuba! To make your arrival into often chaotic Cuba a bit easier, a complimentary transfer from the airport to your accommodation (guesthouse) is included with your trip. Then, enjoy free time until your welcome meeting at 6 pm. If you arrive early there are a wealth of options for you to enjoy in Havana. For a fascinating insight into the Cuban Revolution check out the Museum of the Revolution, indulge your inner literary fan on an Ernest Hemingway tour, join the locals for a stroll past the fading facades along the iconic oceanside Malecon or hire an open top vintage American car and simply cruise the streets and boulevards of Havana. -

Havana House Concierge Havana House Concierge Services

Havana House Concierge Havana House Concierge Services Let us help you enjoy the perfect vacation in Havana and beyond. From reservations at the top restaurants (and secret spots), to private car hire, guides and local experiences; our management is there to make your stay as memorable and magical as possible. Stay at our owner suite or have us help you choose the perfect hotel room or private home. Events We host a wide variety of events at the Havana House. Art Shows and Talks, Rum Tasting, Havana Nights and Music Nights featuring local and International Stars. Or maybe you would like for us to help you create your very own magical night! Art, Art and more Art Check out our One Line Room by Daniel Dugan or our Crown Yourself Art Wall by Karen Bystedt Contemporary Art by Kadar Lopez Lounge by our pool and catch up on emails and news (Yes! We have Wi-Fi) Things to do in and around Havana • Beach Outing • Cigar and Rum Factory Tour (We will escort you to different stops to learn about cigars and the three drinks invented in Cuba: Mojito, Daiquiri and the Cuba Libre. Each drink has its own story to tell) • Santeria ritual (We will take you to the home of a Santeria Priestess to learn about the different deities of the religion and experience a cleansing to rid you of any negative vibes. The cleansing uses herbs, flowers, Holy Water from the Catholic Church and other ingredients) • Day trip to the beach in a vintage American Car (great for photo shoots) • Visit the Taquechel Pharmacy Museum on Calle Obispo No.155 • Baseball Game • Capitol guided tour • Private Dance Lessons • Gay Havana Tour Walking Tours • Walking tour of the 5 plazas of Old Havana. -

22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web : Karl Johans Gt

Tel : +47 22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web :www.reisebazaar.no Karl Johans gt. 23, 0159 Oslo, Norway Cycle Cuba Turkode Destinasjoner Turen starter QBXCC Cuba Havana Turen destinasjon Reisen er levert av 14 dager Havana Fra : NOK 22 722 Oversikt Experience Cuba from two wheels as you cycle around this laidback Caribbean island. Travel the colourful streets of Havana, the dusty roads past the farms and tobacco plantations of Vinales, cycle alongside vintage cars on your way to the verdant Bay of Pigs, discover UNESCO Word Heritage Sites of Cienfuegos and Trinidad and experience Cuba beyond the rum and cigar scene. Pay homage at Che Guevara’s final resting place in Santa Clara, cycle the pristine and untourised Yumuri Valley, and enjoy the perfect beaches of vibrant Varadero, Cayo Jutias’ clear blue waters and cool off in bubbling river pools near Las Terrazas. Soak up the best of Cuba as you traverse this fascinating country. Reiserute Havana Bienvenido a Cuba! To make your arrival into often chaotic Cuba a bit easier a complimentary transfer from the airport to your accommodation (guesthouse) is included with your trip. If you arrive early there are a wealth of options for you to enjoy. For a fascinating insight into the Cuban Revolution check out the Museum of the Revolution, indulge your inner literary fan on an Ernest Hemingway tour, join the locals for a stroll past the fading facades along the iconic oceanside Malecón or hire an open top vintage American car and simply cruise the streets and boulevards of Havana. There’s no shortage of restaurants or bars either – the vibrant Obispo Street area of Old Havana is sure to delight. -

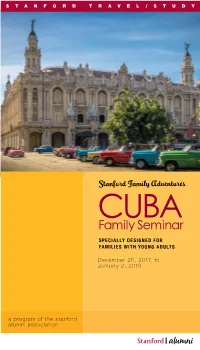

A Program of the Stanford Alumni Association December 26, 2017, To

SHARON JABLON, CUBA FAMILY SEMINAR, 2015 SPECIALLY DESIGNED FOR FAMILIES WITH YOUNG ADULTS December 26, 2017, to January 2, 2018 a program of the stanford alumni association In today’s hectic world it can be difficult for families to get together, especially as kids get older, become more involved with activities and eventually leave the nest. With this in mind, we crafted our Family Seminar programs specifically for families with young adults. And what better destination to explore together as a family than Cuba? It’s a remarkable country with friendly people, a fascinating history and a vibrant culture. On this Family Seminar, parents can travel with their grown children and our knowledgeable faculty leader, Ambassador Karl Eikenberry, MA ’94, taking in the food, music, art and politics of the country. Don’t miss this special educational opportunity to discover a nearby neighbor…and catch up with each other! BRETT S. THOMPSON, ’83, DIRECTOR, STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY Highlights EXPLORE frozen-in-time DISCUSS with CONNECT with other Havana, taking in the dis- community leaders, foreign Stanford families while tinctive architecture, historic policy experts and artists enjoying exclusive educa- sites and pulsating sounds what’s facing Cuba more tional opportunities with of Cuba’s capital. than 50 years after the our faculty leader and local revolution and as the U.S. artists and speakers. seeks to normalize relations. COVER: GRAN TEATRO Faculty Leader KARL EIKENBERRY, MA ’94, is an Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow and professor at Stanford University. His 38-year U.S. government and military career includes serving as ambassador to Afghanistan from 2009 to 2011 and taking on political-military assignments at the Pentagon and in Europe and Asia. -

November 2018

NOVEMBER 2018 Thursday, November 29th Read inside for more information Arthur H. Rice Brent J. Chudachek Chad P. Pugatch Riley W. Cirulnick Kenneth B. Robinson Michael Karsch Ron J. Cohen Richelle B. Levy Craig A. Pugatch George L. Zinkler III Richard B. Storfer ATTORNEYS AT LAW 101 N.E. Third Avenue, Suite 1800, Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33301 954-462-8000 ∙ 954-462-4300 www.rprslaw.com BROWARD COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION Recognizes 100% Membership Club **For firms with 5 attorneys or more** Abramowitz, Pomerantz, & Morehead, P.A. Haliczer, Pettis & Schwamm, P.A. Billing, Cochran, Lyles, Mauro & Ramsey, P.A. Johnson, Anselmo, Murdoch, Burke, Piper & Hochman, P.A. Birnbaum, Lippman & Gregoire, PLLC Keller Landsberg PA Boies Schiller Flexner LLP – Hollywood Office Kelley/Uustal Brinkley Morgan Kim Vaughan Lerner LLP Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney PC Krupnick, Campbell, Malone, Buser, Slama, Catri, Holton, Kessler & Kessler P.A. Hancock & Liberman, P.A. Chimpoulis, Hunter & Lynn, P.A. Legal Aid Service of Broward County Coast to Coast Legal Aid of South Florida MacLean & Ema Cole, Scott, and Kissane Moraitis, Cofar, Karney & Moraitis Colodny Fass Pazos Law Group, P.A. Conrad & Scherer, LLP Rissman, Barrett, Hurt, Donahue, McLain & Mangan, P.A. Cooney Trybus Kwavnick Peets, PLC Rogers, Morris & Ziegler, LLP Doumar, Allsworth, Laystrom, Voigt, Wachs Adair & Dishowitz, LLP Schlesinger Law Offices, P.A. Ferencik, Libanoff, Brandt, Bustamante, & Goldstein, P.A. Seiler, Sautter, Zaden, Rimes & Wahlbrink Fowler, White, Burnett, P.A. Smith, Currie & Hancock, LLP Gladstone & Weissman, P.A. Vezina, Lawrence & Piscitelli, P.A. Gray Robinson, P.A. Walton, Lantaff, Schroeder & Carson, LLP Green, Murphy, Murphy & Kellam Wicker, Smith, O’Hara, McCoy and Ford, P.A. -

Havanareporter YEAR V

THE © YEAR V Nº 7 APR 10, 2015 HAVANA, CUBA avana eporter ISSN 2224-5707 YOUR SOURCE OF NEWS & MORE H R Price: A Weekly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.00 CUC, 1.00 USD, 1.20 CAN Tourism Morro-Cabaña: A Place Worth Visiting/ P.2 Health & Science Cuba Updates Environmental Strategies / P.5 Entertainment & Listings/P.8-9 A Dialogue Photo Feature African Dreams in the is Possible Cuban Grassland/ P.11 / P.6 International Panama Summit: The Possible Scenarios /P.12 UN Target: Gender Equality by 2030/P.13 Economy Cuba-Kuwait: Cooperation City in Keeps Pumping Water/P.14 Motion Sports P.7 Cuba Goes Football Crazy /P.15 BEATLEMANIA IN UBA AS Cuba C , Mariel Zone Lures Over 300 LIVELY AS Foreign Companies EVER/P.10 /P.16 THIS NEWSPAPER IS DISTRIBUTED ON BOARD CUBANA DE AVIACION´S FLIGHTS 2 TOURISM Morro-Cabaña: A Place Worth Visiting Text and Photos By RobertoCAMPOS Meanwhile, the Castillo de la Real Fuerza (Royal Force Castle) began to be built in 1558 and was finished in 1578. The construction of La Punta and El Morro Castle allowed for crossfire against the attackers. The construction of La Punta Castle, which lasted 10 years, was finished in 1600, 30 years earlier than “El Morro,” as The Morro Castle, which has the shape HAVANA._ Close to celebrating 500 A good example is the Morro Castle. it is popularly known. of an irregular polygon, rises 40 meters years of its founding, on November 16, Located at the entrance of the Bay of As ordered by King Carlos III, the above sea level. -

Interview Pegase: “Ambitieuzer Dan Ooit” P

Afgiftekantoor Aalst 1 V.U.: R. Willaert Hanswijkstraat 23 N° 439 B-2800 Mechelen Verschijnt 16x per jaar 24 januari 2020 Erkenningsnr. P902038 EXPLORER PRICES FOR ALL OVER THE WORLD Interview Pegase: “ambitieuzer dan ooit” p. 10-11 bair-BE-travelmagazine-eXperts-LHG-ad-en-85x45-DEC19.indd 20/12/2019 08:52 Hans Vanoorbeek Jeroen Decroos Partner BV Capital Partners Managing director Pegase © Gerrit oOp de Beeck DOSSIER > GOLF & WELLNESS p. 15-19 DOSSIER > DOSSIER ZOMER DEEL I p. 22-33 DOSSIER > MAROKKO p. 36-37 De mooiste bestemmingen naar de Winterzon! Vlieg Eens Vlug Mooie vertrektijden vanaf Maastricht Relaxed & overzichtelijk inclusief gratis parkeren Geen lange wachtrijen 1½ uur van tevoren aanwezig zijn Spanje Turkije Egypte Gambia corendon.be TravelMagazine_A4_Maastricht_19.indd 1 19-07-19 16:16 EDITO INHOUD Coverfoto: Straatbeeld Cienfuegos (Cuba) Nieuw én oud! © Jonas Vandenabeele Actualiteit 2-6 Miles Attack & Teldar Travel: reisagentenweekend Beekse Bergen 7 BCD Travel: “Topkwaliteit dankzij spitstechnologie” 8 Bestemming: De Schotse Hooglanden 9 Het is niet de eerste keer dat hij het begin Coverinterview: van een nieuw jaar – en nog erger een nieuw Hans Vanoorbeek & Jeroen Decroos (Pegase) 10-11 decennium – zelfverklaarde tafelspringers Digitale Economie: Duurzaam reizen in 2020 14 op allerlei fora – zowel op podia als op online posts – pseudo-waarheden, waarschuwingen en voorspellingen ongebreideld de ruimte injagen en dit in verband met alle (nieuwe) en oude travelhypes. Niemand in onze industrie zal ondertussen betwisten of ontkennen dat het omvervallen 15-19 van een megaspeler à la Thomas Cook Dossier Golf & Wellness 15-19 één en ander grondig verandert en dit op Vooral een nicheproduct 15-16 velerlei niveaus. -

Local Level Popular Socialist Development in Havana Cuba: Agriculture, Music, Education, and Health

LOCAL LEVEL POPULAR SOCIALIST DEVELOPMENT IN HAVANA CUBA: AGRICULTURE, MUSIC, EDUCATION, AND HEALTH. by NICOLE HATTIE Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Sociology) Acadia University Fall Graduation 2011 © by NICOLE HATTIE, 2011 i This thesis by NICOLE HATTIE was defended successfully in an oral examination on September 9, 2011. The examining committee for the thesis was: ________________________ Dr. Harish Kapoor, Chair ________________________ Dr. Issac Saney, External Reader ________________________ Dr. Barbara Moore, Internal Reader ________________________ Dr. Jim Sacouman, Supervisor _________________________ Dr. Tony Thompson, Acting as Head/Director This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree Master of Arts (Sociology). …………………………………………. This thesis by NICOLE HATTIE was defended successfully in an oral examination on September 9, 20111 The examining committee for the thesis was: Dr. Harish Kapoor, Chair Dr. Issac Saney, External Reader Dr. Barbara Moore, Internal Reader Dr. Jim Sacouman, Supervisor Dr. Tony Thompson, Acting as Head/Director This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree Master of Arts (Sociology). ii I, NICOLE HATTIE, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or -

Havanareporter SPORTS.AND MORE President: Luis Enrique González

© YEAR IX THE Nº 7 APR 16 , 2019 HAVANA, CUBA ISSN 2224-5707 Price: avana eporter 1.00 CUC H YOUR SOURCE OF NEWSR & MORE 1.00 USD A Monthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.20 CAN Congressman McGovern: Cuba and U.S. Can Have Normal Relations P. 4 Photo Feature Posters Celebrate Havana’s 500 Years P. 11 Health & Science Culture Economy Sports P. 14 P. 15 P. 5 P. 6 Cuba Responds to A Bridge between Cuba Offers a Helping Hand Acosta Danza Honors Cuban and UK Ballet U.S. Blockade by Cuba and The to Mozambique Masters Expanding Markets United States 2 TOURISM A Golden Age for Cuban Tourism By FranciscoMENENDEZ HAVANA.- The 39th edition of the the 12th International Nature Tourism International Tourism Fair, FITCUBA 2019, Meeting, TURNAT 2019, from September undoubtedly draws the attention of tour 23th to 28th. guides, travel agents and professionals Shortly before 2018 came to a close, from the tourist industry, mainly because Cuban Tourism Minister Manuel Marrero Cuba stands as an increasingly attractive said that Havana would be a renewed tourist destination and country in tourist destination in 2019. constant movement. Quality is the main priority, because This dynamic is largely appreciated in Cuba has a number of elements that this sector, which experts identify as the distinguish it from other destinations, most noteworthy not only in the country such as the places designated as a World but in the rest of the Caribbean as well. Heritage Site by UNESCO. This year’s fair features Havana’s 500th Just in the capital, there are 250 anniversary (November 16th), Spain as National Monuments and several the ‘Guest of Honor’ country, and a variety tourist facilities and parks. -

Tour 2 El Vedado

Tour 2 El Vedado Tour No. 2: El Vedado Suggested start time: 9:00 am Approximate travel end time: 6:00 pm Taking advantage of the cool of the morning, if that is possible under the Havana sun, we propose to start this journey through the beautiful neighborhood of El Vedado in the Hotel Riviera (1), 1957 - Avenida Paseo and Malecon. Built with money from gangster Meyer Lansky, it has 20 floors and 352 rooms with sea view. Declared National Monument in 2012, the hotel is a notable example of rationalist architecture of the Modern Movement in Cuba. It was inaugurated on 10 December 1957 with a musical revue presented at the Cabaret Copa Room, which featured a special performance by Ginger Rogers. Climb the stately Avenida Paseo (2) will be nice. Among buildings of the 50s of the last century, beautiful old houses flanking the Republican period. We suggest paying attention to some in particular. Villa Lita (Museum Library Servando Cabrera) (3), 1912 - 13th Street corner Paseo This eclectic architecture mansion was acquired in 1922 by the Italian Emmanuela marriage and Pandini Ong, known as "Lita" and Joseph Pennino and Barbato. The museum that now houses perpetuates the memory of the renowned painter and draftsman Servando Cabrera Moreno (1923 - 1981), who cultivated both abstraction and figuration to form a work characterized by profound humanism, sensuality and aesthetic virtuosity. One block up, at 352 Paseo street corner 15, the House of Pablo Gonzalez de Mendoza (4), 1916- 1918 - is currently the residence of British Ambassador to Cuba. It has gardens to the streets 15 and Paseo, as well as the bottom, with several sculptures and a circular fountain. -

CUBA CONCIERGE SERVICES Havana House Concierge Services

CUBA CONCIERGE SERVICES Havana House Concierge Services • Travel services are provided by our expert Travel partners who will ensure that your trip will be exciting, memorable and safe! • All itineraries are custom tailored and can include flights, visas, restaurants, tours, events, and either hotel or Airbnb accommodation. Your information • Travel Dates • Departure Airport • How many people traveling • Names of all travelers as on passport • Single or double room • Hotel or Airbnb • Havana only or day trips / over-night trips Hotels • Hotel Saratoga • Hotel Parque Central • Hotel Inglaterra • Hotel Sevilla • Kempinski (not available to US residents) • Several great private homes through Airbnb’s (contact us for details) Restaurants • San Cristóbal, Centro Habana municipality. San Rafael Street #469 e/Lealtad y Campanario #7-860-1705 Call and make a reservation. Obama and other celebrities have eaten here. Great food and the ambiance is unique! • La Guardida Concordia No.418 /Gervasio y Escobar. Centro Habana. Ciudad de la Habana. Cuba. Tel: (537) 863-7351, 866-9047 Make reservations. Just re-opened, location of movie Strawberries and Chocolate, it has great atmosphere and fantastic food. In an old mansion, the restaurant is on the top floor. You climb a marble staircase to reach it. • Cocina de Liliam, Vedado, #2096514, 48th between 13/15 some say this is better than La Guarida for food and atmosphere, it is outdoors in a beautiful garden. Closed on Sundays and Mondays. • Vistamar (Avenida 1ra, No. 2206, Playa, 53-7-203-8328; dinner for two around 53 CUC) serves Cuban and Continental food overlooking the Atlantic. Beautiful perfect 50s home, still with original owners, disappearing pool, great sunsets overlooking the ocean (one of the oldest remaining paladars and one of the best). -

35 Strange Facts About Cuba That Most People Don't Know. No One

35 Strange Facts About Cuba That Most People Don’t Know. No One Knows About #32. Cuba is a country that has been shrouded in mystery ever since the United States government banned travel for Americans there in 1962. Since then, Americans haven't been able to explore the country, unless they had explicit permission from their government - or went in via Canada. Now, the United States and Cuba are improving diplomatic relations, and there is talk that soon, we'll all be able to visit the country freely. Still, in the past 50+ years, a lot has transpired. Here are 35 strange facts about the country you probably haven't seen - and some of them will make you want to go as soon as possible. #1. It has snowed once in Cuba: On March 12, 1857. #2. It is mandatory for government vehicles to pick up hitchhikers. #3. A drink of rum and coke and lime is called a "Cuba Libre" in Latin America except in Cuba. There, it's called a "mentirita," or "little lie." #4. In Cuba, ballerinas are at the height of stardom and popularity. In fact, they often earn more money than doctors. #5. Only 5% of Cubans actually have access to the uncensored, open Internet. #6. Cuba is the only country that Americans need government permission to visit. #7. It’s illegal to take a photograph of any military, police or airport personnel in Cuba. #8. Fidel Castro grew a beard because the US embargo cut off his supply of razors. #9. Cross-dressing is illegal in Cuba.