La Magi Du Cinéma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What the Renaissance Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018

What the Renaissance knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know 1 What the Renaissance knew • The 17th Century – For tens of thousands of years, humans had the same view of the universe and of the Earth. – Then the 17th century dramatically changed the history of humankind by changing the way we look at the universe and ourselves. – This happened in a Europe that was apparently imploding politically and militarily, amid massive, pervasive and endless warfare – Grayling refers to "the flowering of genius“: Galileo, Pascal, Kepler, Newton, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Donne, Milton, Racine, Moliere, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Rubens, El Greco, Rembrandt, Vermeer… – Knowledge spread, ideas circulated more freely than people could travel 2 What the Renaissance knew • Collapse of classical dogmas – Aristotelian logic vs Rene Descartes' "Discourse on the Method" (1637) – Galean medicine vs Vesalius' anatomy (1543), Harvey's blood circulation (1628), and Rene Descartes' "Treatise of Man" (1632) – Ptolemaic cosmology vs Copernicus (1530) and Galileo (1632) – Aquinas' synthesis of Aristotle and the Bible vs Thomas Hobbes' synthesis of mechanics (1651) and Pierre Gassendi's synthesis of Epicurean atomism and anatomy (1655) – Papal unity: the Thirty Years War (1618-48) shows endless conflict within Christiandom 3 What the Renaissance knew • Decline of – Feudalism – Chivalry – Holy Roman Empire – Papal Monarchy – City-state – Guilds – Scholastic philosophy – Collectivism (Church, guild, commune) – Gothic architecture 4 What -

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

Phantasmagoria: Ghostly Entertainment of the Victorian Britain

Phantasmagoria: Ghostly entertainment of the Victorian Britain Yurie Nakane / Tsuda College / Tokyo / Japan Abstract Phantasmagoria is an early projection show using an optical instrument called a magic lantern. Brought to Britain from France in 1801, it amused spectators by summoning the spirits of ab- sent people, including both the dead and the living. Its form gradually changed into educational amusement after it came to Britain. However, with the advent of spiritualism, its mysterious na- ture was re-discovered in the form of what was called ‘Pepper’s Ghost’. Phantasmagoria was reborn in Britain as a purely ghostly entertainment, dealing only with spirits of the dead, be- cause of the mixture of the two notions brought from France and the United States. This paper aims to shed light on the role that phantasmagoria played in Britain during the Victorian period, how it changed, and why. Through observing the transnational history of this particular form of entertainment, we can reveal a new relationship between the representations of science and superstitions. Keywords Phantasmagoria, spiritualism, spectacle, ghosts, the Victorian Britain, superstitions Introduction Humans have been mesmerized by lights since ancient times. Handling lights was considered a deed conspiring with magic or witchcraft until the sixteenth century, owing to its sanctified appearance; thus, some performers were put in danger of persecution. At that time, most people, including aristocrats, were not scientifically educated, because science itself was in an early stage of development. However, the flourishing thought of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century altered the situation. Entering the age of reason, people gradually came to regard illusions as worthy of scientific examination. -

Screen Genealogies Screen Genealogies Mediamatters

media Screen Genealogies matters From Optical Device to Environmental Medium edited by craig buckley, Amsterdam University rüdiger campe, Press francesco casetti Screen Genealogies MediaMatters MediaMatters is an international book series published by Amsterdam University Press on current debates about media technology and its extended practices (cultural, social, political, spatial, aesthetic, artistic). The series focuses on critical analysis and theory, exploring the entanglements of materiality and performativity in ‘old’ and ‘new’ media and seeks contributions that engage with today’s (digital) media culture. For more information about the series see: www.aup.nl Screen Genealogies From Optical Device to Environmental Medium Edited by Craig Buckley, Rüdiger Campe, and Francesco Casetti Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by award from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and from Yale University’s Frederick W. Hilles Fund. Cover illustration: Thomas Wilfred, Opus 161 (1966). Digital still image of an analog time- based Lumia work. Photo: Rebecca Vera-Martinez. Carol and Eugene Epstein Collection. Cover design: Suzan Beijer Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 900 0 e-isbn 978 90 4854 395 3 doi 10.5117/9789463729000 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

2015, 41. Jahrgang (Pdf)

Rundfunk und Geschichte Nr. 1-2/2015 ● 41. Jahrgang Interview Leipzig war ein Lebensthema Interview mit Karl Friedrich Reimers anlässlich seines 80. Geburtstags Raphael Rauch Muslime auf Sendung Das „Türkische Geistliche Wort“ im ARD-„Ausländerprogramm“ und islamische Morgenandachten im RIAS Philipp Eins Wettkampf der Finanzierungssysteme Deutsche Presseverleger und öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk im Dauerstreit Andreas Splanemann Auf den Spuren der „Funkprinzessin“ Adele Proesler Christiane Plank Laterna Magica – Technik, Raum, Wahrnehmung Michael Tracey and Christian Herzog British Broadcasting Policy From the Post-Thatcher Years to the Rise of Blair „Und ich hatte ja selbst die Fühler in der Gesellschaft.“ Heinz Adameck (†) im Gespräch Studienkreis-Informationen / Forum / Dissertationsvorhaben / Rezensionen Zeitschrift des Studienkreises Rundfunk und Geschichte e.V. IMPRESSUM Rundfunk und Geschichte ISSN 0175-4351 Selbstverlag des Herausgebers erscheint zweimal jährlich Zitierweise: RuG - ISSN 0175-4351 Herausgeber Studienkreis Rundfunk und Geschichte e.V. / www.rundfunkundgeschichte.de Beratende Beiratsmitglieder Dr. Alexander Badenoch, Utrecht Dr. Christoph Classen, ZZF Potsdam Prof. Dr. Michael Crone, Frankfurt/M. Redaktion dieser Ausgabe Dr. Margarete Keilacker, verantwortl. (E-Mail: [email protected]) Melanie Fritscher-Fehr (E-Mail: [email protected]) Dr. Judith Kretzschmar (E-Mail: [email protected]) Martin Stallmann (E-Mail: [email protected]) Alina Laura Tiews (E-Mail: -

Mid-Victorian Fiction and Moving-Image Technologies

Durham E-Theses The Eye in Motion: Mid-Victorian Fiction and Moving-Image Technologies BUSH, NICOLE,SAMANTHA How to cite: BUSH, NICOLE,SAMANTHA (2015) The Eye in Motion: Mid-Victorian Fiction and Moving-Image Technologies , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11124/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Eye in Motion: Mid-Victorian Fiction and Moving-Image Technologies Nicole Bush Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Studies Durham University January 2015 Abstract This thesis reads selected works of fiction by three mid-Victorian writers (Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, and George Eliot) alongside contemporaneous innovations and developments in moving-image technologies, or what have been referred to by historians of film as ‘pre-cinematic devices’. -

Project Aneurin

The Aneurin Great War Project: Timeline Part 6 - The Georgian Wars, 1764 to 1815 Copyright Notice: This material was written and published in Wales by Derek J. Smith (Chartered Engineer). It forms part of a multifile e-learning resource, and subject only to acknowledging Derek J. Smith's rights under international copyright law to be identified as author may be freely downloaded and printed off in single complete copies solely for the purposes of private study and/or review. Commercial exploitation rights are reserved. The remote hyperlinks have been selected for the academic appropriacy of their contents; they were free of offensive and litigious content when selected, and will be periodically checked to have remained so. Copyright © 2013-2021, Derek J. Smith. First published 09:00 BST 30th May 2013. This version 09:00 GMT 20th January 2021 [BUT UNDER CONSTANT EXTENSION AND CORRECTION, SO CHECK AGAIN SOON] This timeline supports the Aneurin series of interdisciplinary scientific reflections on why the Great War failed so singularly in its bid to be The War to End all Wars. It presents actual or best-guess historical event and introduces theoretical issues of cognitive science as they become relevant. UPWARD Author's Home Page Project Aneurin, Scope and Aims Master References List BACKWARD IN TIME Part 1 - (Ape)men at War, Prehistory to 730 Part 2 - Royal Wars (Without Gunpowder), 731 to 1272 Part 3 - Royal Wars (With Gunpowder), 1273-1602 Part 4 - The Religious Civil Wars, 1603-1661 Part 5 - Imperial Wars, 1662-1763 FORWARD IN TIME Part -

1570 Fm 1..12

MediaArtHistories LEONARDO Roger F. Malina, Executive Editor Sean Cubitt, Editor-in-Chief The Visual Mind, edited by Michele Emmer, 1993 Leonardo Almanac, edited by Craig Harris, 1994 Designing Information Technology, Richard Coyne, 1995 Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, edited by Mary Anne Moser with Douglas MacLeod, 1996 Technoromanticism: Digital Narrative, Holism, and the Romance of the Real, Richard Coyne, 1999 Art and Innovation: The Xerox PARC Artist-in-Residence Program, edited by Craig Harris, 1999 The Digital Dialectic: New Essays on New Media, edited by Peter Lunenfeld, 1999 The Robot in the Garden: Telerobotics and Telepistemology in the Age of the Internet, edited by Ken Goldberg, 2000 The Language of New Media, Lev Manovich, 2001 Metal and Flesh: The Evolution of Man: Technology Takes Over, Ollivier Dyens, 2001 Uncanny Networks: Dialogues with the Virtual Intelligentsia, Geert Lovink, 2002 Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology, Stephen Wilson, 2002 Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, Oliver Grau, 2003 Women, Art, and Technology, edited by Judy Malloy, 2003 Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization, Alexander R. Galloway, 2004 At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet, edited by Annmarie Chandler and Norie Neumark, 2005 The Visual Mind II, edited by Michele Emmer, 2005 CODE: Collaborative Ownership and the Digital Economy, edited by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh, 2005 The Global Genome: Biotechnology, Politics, and Culture, Eugene Thacker, 2005 Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture, Matthew Fuller, 2005 Art Beyond Biology, edited by Eduardo Kac, 2006 New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts, and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, 2006 Aesthetic Computing, edited by Paul A. -

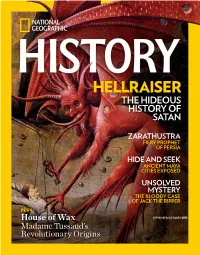

Hellraiser the Hideous History of Satan

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS HELLRAISER THE HIDEOUS HISTORY OF SATAN ZARATHUSTRA FIERY PROPHET OF PERSIA HIDE AND SEEK ANCIENT MAYA CITIES EXPOSED UNSOLVED MYSTERY THE BLOODY CASE OF JACK THE RIPPER PLUS: House of Wax SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 Madame Tussaud’s Revolutionary Origins РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS FROM THE EDITOR ORONOZ/ALBUM If you close your eyes and imagine evil, what do you see? A scarlet man with horns and a pitchfork? A pair of glowing eyes glaring in the dark? A dark force thriving on fear and pain? Evil has many incarnations, and in this issue, HISTORY explores two of them—one spiritual and the other physical. The first article delves into medieval Christian art to show how the devil’s appearance evolved over centuries from fallen angel to horned monster, like the one shown above in this 15th-century Spanish altarpiece. In many of these artworks, evil is vividly rendered as an ugly, slavering beast awaiting sinful souls to punish in hell. In the story of Jack the Ripper, evil is a mystery man: predatory, anonymous, and elusive. Dwelling in the shadows, it inflicts horror on the living. Unidentified, it can’t be sketched or photographed. The only proof of its existence are the brutalized bodies of its victims, killed in one short season in 1888. Unlike the garish, medieval images of the devil, Jack the Ripper lived in the dark: unshackled and unpunished— an evil defined by both its physical absence and malevolent presence. -

Small, Douglas Robert John (2013) Dementia's Jester: the Phantasmagoria in Metaphor and Aesthetics from 1700-1900

Small, Douglas Robert John (2013) Dementia's jester: the Phantasmagoria in metaphor and aesthetics from 1700-1900. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4212/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Dementia’s Jester: The Phantasmagoria in Metaphor and Aesthetics from 1700 – 1900. Douglas Robert John Small PhD in English Literature University of Glasgow Department of English Literature – School of Critical Studies September 2012 © Douglas Robert John Small, September 2012 This work is dedicated, with deepest love and gratitude, to my mother and father, Elizabeth and Drummond Small, and to my sister Lynsay. I cannot thank you enough for everything you’ve done for me. I would like to thank Gillian McCay and Tom Russon for being wonderful people who looked after me and took me to see art, and the fabulous Miss Maryann Cowie, for always being there and always being the best of friends. Special mentions go to Felicity Maxwell (for being a Scholar and a Gentleman of the Old School), Daria Izdebska (for many fun conversations and much good advice), and Tania Scott (for numerous lunches, cups of tea and generally being a sweetheart). -

Introduction

1 Introduction The English word “museum” comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as “museums” (or rarely, “musea”). It is originally from the Ancient Greek (Mouseion), which denotes a place or temple dedicated to the Muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence a building set apart for study and the arts, especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and research atAlexandria by Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BCE. The first museum/library is considered to be the one of Plato in Athens. However, Pausanias gives another place called “Museum,” namely a small hill in Classical Athens opposite the Akropolis. The hill was called Mouseion after Mousaious, a man who used to sing on the hill and died there of old age and was subsequently buried there as well. The Louvre in Paris France. 2 Museum The Uffizi Gallery, the most visited museum in Italy and an important museum in the world. Viw toward thePalazzo Vecchio, in Florence. An example of a very small museum: A maritime museum located in the village of Bolungarvík, Vestfirðir, Iceland showing a 19th-century fishing base: typical boat of the period and associated industrial buildings. A museum is an institution that cares for (conserves) a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic,cultural, historical, or scientific importance and some public museums makes them available for public viewing through exhibits that may be permanent or temporary. The State Historical Museum inMoscow. Introduction 3 Most large museums are located in major cities throughout the world and more local ones exist in smaller cities, towns and even the countryside. -

The Phantasmagoric Dispositif: an Assembly of Bodies and Images in Real Time and Space

The Phantasmagoria, frontispiece from Étienne-Gaspard Robertson, Mémoires récréatifs, scientifiques et anecdotiques (1831–1833). 42 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00187 The Phantasmagoric Dispositi f: An Assembly of Bodies and Images in Real Time and Space NOAM M. ELCOTT Resurrection Redux In this exhibition, a lUminoUs figUre, representing sometimes a skeleton, and sometimes the head of some eminent person, appeared before the spectators, who were seated in a dark chamber. It grew less and less, and seemed to retire to a great distance. It again advanced, and conseqUently increased in size, and having retired a second time, it appeared to vanish in a lUminoUs cloUd, from which another figUre gradUally arose, and advanced and retreated as before. 1 The piece is a kind of cave—or UndergroUnd-like hall—very dark. From an Unseen soUrce black-and-white images of twelve different people are projected all along the walls. When yoU approach the image, say, of a distant seated person and stand before her or him, she or he responds to yoUr presence by getting Up and walking straight Up to yoU, there to remain, “life- size,” for a longish period simply standing and looking at yoU. If yoU leave, or if yoU stand there too long, the person tUrns aroUnd and goes back to the original spot and sits down. 2 Two exhibitions separated by two hUndred years. The first premiered officially in 1790s Paris—an earlier version had been staged in Leipzig—and spread to EUropean capitals sUch as London. Part enlightened entertainment, part haUnted hoUse, the Phantasmagoria, like its descendant two hUndred years later, refUsed categoriza - tion as mere magic lantern spectacle.