AN INITIAL RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-BORO-GARO by DANIEL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Allan, Keith. 1977. ‘Classifiers’, Language 53: 285–311. Benedict, Paul King (Contributing Editor: James Alan Matisoff ). 1972. Sino-Tibetan: A Conspectus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bhattacharya, Promod Chandra. 1977. A Descriptive Analysis of Boro. Gauhati: Guwahati University, Department of Publication. Bauer, Laurie. 1983. English Word-formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bhat, D.N. Shankara. 1968. Boro Vocabulary (With a Grammatical Sketch). Poona: Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. Blake, Barry J. 1994. Case. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bradley, David. 1994. ‘The subgrouping of Tibeto-Burman’, pp. 59–78 in Hajime Kitamura, Tatsuo Nishida and Yasuhiko Nagano (eds.) Current Issues in Sino-Tibetan Linguistics. Osaka: The organizing Committee, The 26th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics. Breton, Roland J.-L. 1977. Atlas of the Languages and Ethnic Communities of South Asia. New Delhi: Sage Publications. Burling, Robbins. 1959. ‘Proto-Bodo’, Language ( Journal of the Linguistic Society of America) 35: 433–453. ——. 1961. A Garo Grammar. Poona: Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. ——. 1981. ‘Garo spelling and Garo phonology’, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 6 (1): 61–81. ——. 1983. ‘The Sal languages’, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 7 (2): 1–31. ——. 1984. ‘Noun compounding in Garo’, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 8 (1): 14–42. ——. 1992. ‘Garo as a minimal tone language’, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 15 (2): 33–51. Burton-Page, J. 1955. ‘An analysis of the syllable in Boro’, Indian Linguistics ( Journal of the Linguistic Society of India, incorporating the Indian Philological Association) 16: 334–344. Comrie, Bernard. 1985. Tense. -

Dept of English Tripura University Faculty Profile Name

Dept of English Tripura University Faculty Profile Name: Kshetrimayum Premchandra (PhD) Designation: Assistant Professor Academic Qualification: BA (Hindu College, Delhi University), MA, PhD (Manipur University) Subjects Taught: Northeast (Indian) Literatures, Drama (Performance Theory), Folklore Mail: [email protected], [email protected] Landline/Intercom: +91 381237-9445 Fax: 03812374802 Mobile: +91 9436780234 1. List of publications as chapters, proceedings and articles in books and journals S. ISBN/ISSN No Title with page nos. Book/Journal No . Law of the Mother: The Mothers of Maya Spectrum, June, 2014, Vol. 2, ISSN 2319-6076 1 Diip, , pp. 12-18 Issue 1 Blood, Bullet, Bomb, and Voices in the Spectrum, June, 2015, Vol. 3, ISSN 2319-6076 2 The Sound of Khongji, pp. 11-18 Issue 1, The Hanndmaid’s Tale: The Curse of Spectrum, July- Vol. 3, Issue 2, ISSN 2319-6076 3 Being ‘Fertile’, pp. 19-27 Dec., 2015, Transcript, Bodoland 4 Place of Ougri in Meitei Lai Haraoba ISSN 2347-1743 University. Vol III, pp. 81-89 Of Pilgrims and Savages in the Heart of ISSN 2319-6076 5 Spectrum Darkness Journal of Literature and Incest and Gender Bias in the Tripuri Cultural Studies, Mizoram 6 ISSN 2348-1188 Folktale “Chethuang” University. Vol V, Issue II, Dec. 2018. Pp. 87-98. Nationalist Thought and the ISBN 978-93- “Death Journey: The Nigger of the Colonial World, 7 81142-92-9 ‘Narcissus’”, pp. 126-136. Ram Sharma et. al., New Delhi: Mangalam Publications Manipuri Dance and Culture: An Anthology. The Notions of Manipuri Identity, ISBN 978-81- 8 Ed. Adhikarimayum pp. 160-181. -

On Nominal Relational Morphology in Tibeto-Burman

On Nominal Relational Morphology in Tibeto-Burman Randy J. LaPoUa Olf~ !IHIf~# ) J!l.t'J M~i:.1!lJ c~ •• ~ ~ : •• ~~ ~ ~a ••• ~.) #. ~ it li ff liJ. :$ ff t' j,f 7;: ,\., tU' ff i'J 1; '!i' I/li *'l <f !I< 'if 11, I'>t ~ ~ # 'if 11, ,o1i LANGUAGE AND LlNGUISTlCS M ONOGRAPH SERIES NUMBER WA Studies on Sillo-Tibetall Lallgllages Papers ill HOIwr 0/ Professor HW(lIIg-c:llemg Gong Oll His Seventieth Birllu[llY Edited by Ving-ch in Li n, Fang-min Hsu, Chun-chi h Lee, Jackson T.-S. Sun, Hsiu-fang Yang and Dah-an Ho In stitute of Lingui slics Academia Sin ica, Taipei, Taiwan 2004 Sludies on Smo·Tlbe/an Languages, 43·73 2004-8-004-001-000120-2 On Nominal Relational Morphology in Tibeto-Burman* " Randy J_ LaPolla La Trabe fUversity For this paper, 170 Tibeto-Burman were surveyed for nominal ease marking (adpositions), in an attempt to determine ifit would be possible to reeonstruet any ease markers to Proto· Tibeto-Burman, and in so doing leam more about the nature of the grammatieal organization of Proto-Tibeto-Burman. The data were also eross-cheeked for patterns of isomorphy/polysemy, to see ifwe can leam anything about the development ofthe forms we da find in the languages. The results ofthe survey indicate that although a11 Tibeto-Bunnan languages have developed some sort of relation marking, none of the markers ean be reconstrueted to the oldest stage of the family. Looking at the patterns of isomorphy or polysemy, we find there are regularities to the patterns we find, and on the basis of these regularities we can make assurne that the path of development most probably followed the markedness/prototypicality clines: the locative and ablative use would have arose first and then were extended to the more abstract cases. -

Morphological Analyzer for Kokborok

Morphological Analyzer for Kokborok Khumbar Debbarma1 Braja Gopal Patra2 Dipankar Das3 Sivaji Bandyopadhyay2 (1) TRIPURA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, Agartala, India (2) JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY, Kolkata, India (3) NATIONAL INSTITUTE_OF TECHNOLOGY, Meghalaya, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],[email protected] ABSTRACT Morphological analysis is concerned with retrieving the syntactic and morphological properties or the meaning of a morphologically complex word. Morphological analysis retrieves the grammatical features and properties of an inflected word. However, this paper introduces the design and implementation of a Morphological Analyzer for Kokborok, a resource constrained and less computerized Indian language. A database driven affix stripping algorithm has been used to design the Morphological Analyzer. It analyzes the Kokborok word forms and produces several grammatical information associated with the words. The Morphological Analyzer for Kokborok has been tested on 56732 Kokborok words; thereby an accuracy of 80% has been obtained on a manual check. KEYWORDS : Morphology Analyzer, Kokborok, Dictionary, Stemmer, Prefix, Suffix. Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on South and Southeast Asian Natural Language Processing (SANLP), pages 41–52, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 41 1 Introduction Kokborok is the native language of Tripura and is also spoken in the neighboring states like Assam, Manipur, Mizoram as well as the countries like Bangladesh, Myanmar etc., comprising of more than 2.5 millions1 of people. Kokborok belongs to the Tibeto-Burman (TB) language falling under the Sino language family of East Asia and South East Asia2. Kokborok shares the genetic features of TB languages that include phonemic tone, widespread stem homophony, subject- object-verb (SOV) word order, agglutinative verb morphology, verb derivational suffixes originating from the semantic bleaching of verbs, duplication or elaboration. -

Word-Order in Boro Language

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Word-Order in Boro Language Dr. Kanun Basumatary Guest Lecturer, North Eastern Regional Language Centre Guwahati-29, Assam, India Abstract: The present study attempts to analysis and to discuss about the word-order of the Boro language. The Boro language is originated from the Tibeto-Burman group of Sino-Tibetan language family. The language is mainly spoken in Assam and its adjacent areas or countries of India. Like Nepal, Meghalaya, Bangladesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, West Bengal etc. The Boro language has some special features in terms of using word-order pattern and it found in different types. The Boro language is found in SOV word-order pattern mainly and along with this pattern there are different types of word- orders in that language. The Tibeto-Burman languages are found in verb-final position. The Boro language is same in such feature. Keywords : Word-order, Boro, Language, SOV, OSV 1. Introduction Boro is the name of the community as well as the language. The Boro language belongs to Sino- Tibetan language family. This stock originated in the plain areas of Yang-Tsze-Kiang and Huang-ho rivers in China. Now, this language family is well spread throughout the eastern and south-eastern parts of Asia including Burma and North eastern parts of India including Assam (MR Baro, 2007:1). The Boro language originated from the Tibeto-Burman sub family of Sino-Tibetan language family. Its well spread throughout the Assam specially in the northern parts of Assam and its adjacent areas. -

Ginuxsko-Russkij Slovar' by M. Š. Xalilov and I

Anthropological Linguistics Trustees of Indiana University Review Reviewed Work(s): Ginuxsko-russkij slovar' by M. Š. Xalilov and I. A. Isakov Review by: Maria Polinsky and Kirill Shklovsky Source: Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 49, No. 3/4 (Fall - Winter, 2007), pp. 445-449 Published by: The Trustees of Indiana University on behalf of Anthropological Linguistics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27667619 Accessed: 19-01-2017 20:10 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Anthropological Linguistics, Trustees of Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropological Linguistics This content downloaded from 129.2.19.102 on Thu, 19 Jan 2017 20:10:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 2007 Book Reviews 445 References Aikhenvald, Alexandra 2000 Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Devices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Baruah, Nagendra Nath 1992 A Trilingual Dimasha-English-Assamese Dictionary. Guwahati: Publica tion Board Assam. Bhattacharya, Pramod Chandra 1977 A Descriptive Analysis of the Boro Language. Gauhati: Department of Publication, Gauhati University. Bradley, David 2001 Counting the Family: Family Group Classifiers in Yi Branch Languages. Anthropological Linguistics 43:1-17. Burling, Robbins 1961 A Garo Grammar. -

Lz-^ P-,^-=O.,U-- 15 15 No

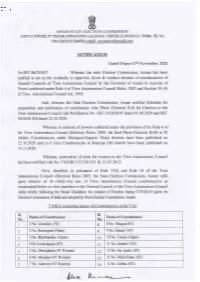

ASSAM STATE ELECTION COMMISSION ADITYA TOWER, 2}TD FI.,OO& DO\AAITO\^AI, G.S. ROAD DISPUR, GUWAHATI -781W. PTT. NO. M1263210/ 2264920 email - [email protected] NOTIFICATION Dated Dispur 17m November,2020 No.SEC.86l2020l7 : Whereas, the state Election Commission, Assam has been notified to act as the Authority to supervise, direct & conduct election of constituencies of General Councils of Tiwa Autonomous Council by the Governor of Assam in exercise of Power conferred under Rule 4 of Tiwa Autonomous Council Rules, 2005 and Section 50 (4) of Tiwa Autonomous Council Act, 1995; And, whereas, the State Election Commission, Assam notified Schedule for preparation and publication of constituency wise Photo Electoral Roll for Election to the Tiwa Autonomous Council vide Notification No. 5EC.5412020147 dated 01 .09.2020 and SEC 5 4 I 2020 I | 0 4 dated 22.1 0 .2020 ; Whereas, in exercise of powers conferred under the provision of the Rule 4 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules, 2005, the final Photo Electoral Rolls in 30 (thirty) Constituencies under MorigaonA.lagaonl Hojai districts have been published on 22.10.2020 and in 6 (six) Constituencies in Kamrup (M) district have been published on t5.rr.2020; Whereas, reservation of seats for women in the Tiwa Autonomous Council has been notified vide No. TAD/BC/I5712015151 dt.21.07.2015; Now, therefore, in pursuance of Rule 17(I) and Rule 18 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules 2005, the State Election Commission, Assam calls upon electors of 36 (thirfy-six) nos. of Tiwa Autonomous Council constituencies as enumerated below to elect members to the General Council of the Tiwa Autonomous Council while sfictly following the Broad Guidelines for conduct of Election dwing COVID-l9 given by Election Commission of India and adopted by State Election Commissioq Assam TABLE consistins names of Constituencies of the TAC sl. -

Sanskrit Alphabet

Sounds Sanskrit Alphabet with sounds with other letters: eg's: Vowels: a* aa kaa short and long ◌ к I ii ◌ ◌ к kii u uu ◌ ◌ к kuu r also shows as a small backwards hook ri* rri* on top when it preceeds a letter (rpa) and a ◌ ◌ down/left bar when comes after (kra) lri lree ◌ ◌ к klri e ai ◌ ◌ к ke o au* ◌ ◌ к kau am: ah ◌ं ◌ः कः kah Consonants: к ka х kha ga gha na Ê ca cha ja jha* na ta tha Ú da dha na* ta tha Ú da dha na pa pha º ba bha ma Semivowels: ya ra la* va Sibilants: sa ш sa sa ha ksa** (**Compound Consonant. See next page) *Modern/ Hindi Versions a Other ऋ r ॠ rr La, Laa (retro) औ au aum (stylized) ◌ silences the vowel, eg: к kam झ jha Numero: ण na (retro) १ ५ ॰ la 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 @ Davidya.ca Page 1 Sounds Numero: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 १॰ ॰ १ २ ३ ४ ६ ७ varient: ५ ८ (shoonya eka- dva- tri- catúr- pancha- sás- saptán- astá- návan- dásan- = empty) works like our Arabic numbers @ Davidya.ca Compound Consanants: When 2 or more consonants are together, they blend into a compound letter. The 12 most common: jna/ tra ttagya dya ddhya ksa kta kra hma hna hva examples: for a whole chart, see: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/devanagari_conjuncts.php that page includes a download link but note the site uses the modern form Page 2 Alphabet Devanagari Alphabet : к х Ê Ú Ú º ш @ Davidya.ca Page 3 Pronounce Vowels T pronounce Consonants pronounce Semivowels pronounce 1 a g Another 17 к ka v Kit 42 ya p Yoga 2 aa g fAther 18 х kha v blocKHead -

KHA in ANCIENT INDIAN MATHEMATICS It Was in Ancient

KHA IN ANCIENT INDIAN MATHEMATICS AMARTYA KUMAR DUTTA It was in ancient India that zero received its first clear acceptance as an integer in its own right. In 628 CE, Brahmagupta describes in detail rules of operations with integers | positive, negative and zero | and thus, in effect, imparts a ring structure on integers with zero as the additive identity. The various Sanskrit names for zero include kha, ´s¯unya, p¯urn. a. There was an awareness about the perils of zero and yet ancient Indian mathematicians not only embraced zero as an integer but allowed it to participate in all four arithmetic operations, including as a divisor in a division. But division by zero is strictly forbidden in the present edifice of mathematics. Consequently, verses from ancient stalwarts like Brahmagupta and Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya referring to numbers with \zero in the denominator" shock the modern reader. Certain examples in the B¯ıjagan. ita (1150 CE) of Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya appear as absurd nonsense. But then there was a time when square roots of negative numbers were considered non- existent and forbidden; even the validity of subtracting a bigger number from a smaller number (i.e., the existence of negative numbers) took a long time to gain universal acceptance. Is it not possible that we too have confined ourselves to a certain safe convention regarding the zero and that there could be other approaches where the ideas of Brahmagupta and Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya, and even the examples of Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya, will appear not only valid but even natural? Enterprising modern mathematicians have created elaborate legal (or technical) machinery to overcome the limitations imposed by the prohibition against use of zero in the denominator. -

South Asian Perspectives on Relative‑Correlative Constructions

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. South Asian perspectives on relative‑correlative constructions Coupe, Alexander Robertson 2018 Coupe, A. R. (2018). South Asian perspectives on relative‑correlative constructions. The 51st International Conference on Sino‑Tibetan Languages and Linguistics. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/89999 © 2018 The Author (s) . All rights reserved. This paper was published in The 51st International Conference on Sino‑Tibetan Languages and Linguistics and is made available with permission of The Author (s). Downloaded on 29 Sep 2021 04:59:51 SGT Paper presented at the 51st International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Kyoto University, 25–28 September 2018 Draft only - comments solicited South Asian perspectives on relative-correlative constructions Alexander R. Coupe [email protected] Nanyang Technological University Singapore Abstract This paper discusses relativization strategies used by South Asian languages, with the focus falling on relative-correlative constructions. The bi-clausal relative-correlative structure is believed to be native to Indo-Aryan languages and has been replicated by Austroasiatic, Dravidian and Tibeto-Burman languages of South Asia through contact and convergence, despite the non-Indic languages of the region already having a participial relativization strategy at their disposal. Various permutations of the relative-correlative construction are discussed and compared to the participial relativization strategies of South Asian languages, and functional reasons are proposed for its widespread diffusion and distribution. 1 Introduction This paper surveys a sample of languages of South Asia that have bi-clausal structures closely resembling the relative-correlative clause construction native to Indic languages, which are thought to be the source of constructions having the same function and a very similar structure in many Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman and Dravidian languages. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

CONFERENCE REPORT the 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE of the NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 33.1 — April 2010 CONFERENCE REPORT THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Stephen Morey La Trobe University The 5th conference of the North East Indian Linguistics Society (NEILS) was held from 12th to 14th February 2010 at the Don Bosco Institute (DBI), Kharguli Hills, Guwahati, Assam. The conference was preceded by a two day workshop, hosted by Gauhati University,1 but also held at DBI. NEILS is grateful to the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, for providing funds to assist in the running of the workshops and conference. The two day workshop was in two parts: one day on using the Toolbox program, run by Virginia and David Phillips of SIL; and one day on working with tones, presented by Mark W. Post, Stephen Morey and Priyankoo Sarmah. Both workshops were well-attended and participatory in nature. The tones workshop included an intensive session of the Boro language, with five native speakers, all students of the Gauhati University Linguistics Department, providing information on their language and interacting with the participants. The conference itself began on 12th February with the launch of Morey and Post (2010) North East Indian Linguistics, Volume 2, performed by Nayan J. Kakoty, Resident Area Manager of Cambridge University Press India. This volume contains peer-reviewed and edited papers from the 2nd NEILS conference, held in 2007, representing NEILS’ commitment to the publication of the conference papers. A notable feature of the conference was the presence of seven people, from India, Burma, Australia and Germany, working on the Tangsa group of languages spoken on the India-Burma border.