Dykes on Irises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plants Species of Community Interest Identified in the Flora of the Transylvanian Plain (Mureş County)

Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldiş”, Seria Ştiinţele Vieţii Vol. 27 issue 3, 2017, pp 209-214 © 2017 Vasile Goldis University Press (www.studiauniversitatis.ro) PLANTS SPECIES OF COMMUNITY INTEREST IDENTIFIED IN THE FLORA OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN PLAIN (MUREŞ COUNTY) Silvia OROIAN*1, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2, Corneliu TĂNASE3 1,3 University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy Tîrgu Mureş 2 Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences Tîrgu Mureş ABSTRACT: The purpose of this study is to present the species of community interest identified in the cormoflora of the Transylvanian Plain (Mureş County) as well as to verify in the field the existing chorological information, to select the endangered plant categories and to highlight the main populations of valuable species. Because of the location of the region, the diversity of the reliefs (hills, meadows), the various exhibitions and inclinations of the slopes, the Transylvanian Plain is distinguished by a great diversity of vegetal taxa (Oroian, Sămărghițan, 2014). The target species were the species of community interest listed in the Annexes to the Habitats Directive and those of O.U.G. no.57/2007. KEYWORDS: conservation status, Mureş county, Transylvania INTRODUCTION: taking in consideration authors experience and The Transylvanian Plain is represented by the previous personal field researches. central part of the Transylvanian Depression and extends on the territory of three counties: Bistriţa- RESULTS: Năsăud, Mureş and Cluj. In the territory of Mureş In the study area, seven species of community County, the Transylvanian Plain, situated to the north interest were identified. Of these: of the Mureş River, is a region formed by hills with an 4 species are LC (least concern) – Lowest average altitude of 400 m and is walled by the wide risk; does not qualify for a higher risk category. -

A HANDBOOK of GARDEN IRISES by W

A HANDBOOK OF GARDEN IRISES By W. R. DYKES, M.A., L.-ès-L. SECRETARY OF THE ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. AUTHOR OF "THE GENUS IRIS," ETC. CONTENTS. PAGE PREFACE 3 1 THE PARTS OF THE IRTS FLOWER AND PLANT 4 2 THE VARIOUS SECTIONS OF THE GENUS AND 5 THEIR DISTRIBUTION 3 THE GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE VARIOUS 10 SECTIONS AND SPECIES AND THEIR RELATIVE AGES 4 THE NEPALENSIS SECTION 13 5 THE GYNANDRIRIS SECTION 15 6 THE RETICULATA SECTION 16 7 THE JUNO SECTION 23 8 THE XIPHIUM SECTION 33 9 THE EVANSIA SECTION 40 10 THE PARDANTHOPSIS SECTION 45 11 THE APOGON SECTION 46 — THE SIBIRICA SUBSECTION 47 — THE SPURIA SUBSECTION 53 — THE CALIFORNIAN SUBSECTION 59 — THE LONGIPETALA SUBSECTION 64 — THE HEXAGONA SUBSECTION 67 — MISCELLANEOUS BEARDLESS IRISES 69 12 THE ONCOCYCLUS SECTION 77 I. Polyhymnia, a Regeliocydus hybrid. 13 THE REGELIA SECTION 83 (I. Korolkowi x I. susianna). 14 THE PSEUDOREGELIA SECTION 88 15 THE POGONIRIS SECTION 90 16 GARDEN BEARDED IRISES 108 17 A NOTE ON CULTIVATION, ON RAISING 114 SEEDLINGS AND ON DISEASES 18 A TABLE OF TIMES OF PLANTING AND FLOWERING 116 19 A LIST OF SYNONYMS SOMETIMES USED IN 121 GARDENS This edition is copyright © The Goup for Beardless Irises 2009 - All Rights Reserved It may be distributed for educational purposes in this format as long as no fee (or other consideration) is involved. www.beardlessiris.org PREFACE TO THIS DIGITAL EDITION William Rickatson Dykes (1877-1925) had the advantage of growing irises for many years before writing about them. This Handbook published in 1924 represents the accumulation of a lifetime’s knowledge. -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

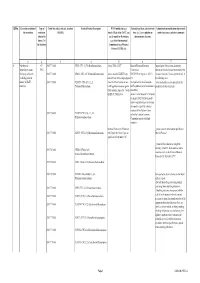

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

1 Acanthus Dioscoridis Acanthaceae 2 Blepharis Persica Acanthaceae 3

Row Species Name Family 1 Acanthus dioscoridis Acanthaceae 2 Blepharis persica Acanthaceae 3 Acer mazandaranicum Aceraceae 4 Acer monspessulanum subsp. persicum Aceraceae 5 Acer monspessulanum subsp. assyriacum Aceraceae 6 Acer monspessulanum subsp. cinerascens Aceraceae 7 Acer monspessulanum subsp. turcomanicum Aceraceae 8 Acer tataricum Aceraceae 9 Acer campestre Aceraceae 10 Acer cappadocicum Aceraceae 11 Acer monspessulanum subsp. ibericum Aceraceae 12 Acer hyrcanum Aceraceae 13 Acer platanoides Aceraceae 14 Acer velutinum Aceraceae 15 Aizoon hispanicum Aizoaceae 16 Mesembryanthemum nodiflorum Aizoaceae 17 Sesuvium verrucosum Aizoaceae 18 Zaleya govindia Aizoaceae 19 Aizoon canariense Aizoaceae 20 Alisma gramineum Alismataceae 21 Damasonium alisma Alismataceae 22 Alisma lanceolatum Alismataceae 23 Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae 24 Sagittaria trifolia Alismataceae 25 Allium assadii Alliaceae Row Species Name Family 26 Allium breviscapum Alliaceae 27 Allium bungei Alliaceae 28 Allium chloroneurum Alliaceae 29 Allium ellisii Alliaceae 30 Allium esfandiarii Alliaceae 31 Allium fedtschenkoi Alliaceae 32 Allium hirtifolium Alliaceae 33 Allium kirindicum Alliaceae 34 Allium kotschyi Alliaceae 35 Allium lalesaricum Alliaceae 36 Allium longivaginatum Alliaceae 37 Allium minutiflorum Alliaceae 38 Allium shelkovnikovii Alliaceae 39 Allium subnotabile Alliaceae 40 Allium subvineale Alliaceae 41 Allium wendelboi Alliaceae 42 Nectaroscordum koelzii Alliaceae 43 Allium akaka Alliaceae 44 Allium altissimum Alliaceae 45 Allium ampeloprasum subsp. -

Midwest Regional Hosta Society Newsletter Hosta Leaves Issue Number 70 Spring 2011

MIDWEST REGIONAL HOSTA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER HOSTA LEAVES ISSUE NUMBER 70 SPRING 2011 WINTER SCIENTIFIC MEETING MADISON, WISCONSIN CONVENTION President Vice-President Secretary Treasurer Editor Lou Horton Mary Ann Metz Glenn Herold Barb Schroeder Floyd Rogers 1N735 Ingalton 1108 W. William St. 1004 W. Northcrest Ave 1819 Coventry Dr 22W213 Glen Valley Dr West Chicago, IL 60190 Champaign, IL 61821 Peoria, IL 61614 Champaign, IL 61822 Glen Ellyn, IL 60137 President‟s Message A very successful Winter Scientific Meeting is behind us now as (I devoutly hope) is a pretty tough winter. The WSM was moved to a new venue at the Wyndham hotel in Lisle, IL this year and from all reports, the change worked for all involved. We had excellent attendance and the speakers all came through with excellent presentations. For those MRHS members who could not attend, all is not lost as we have presentation summaries in this issue of Hosta Leaves. The 2012 edition of the Winter Scientific is set for Saturday, January 21st. The folks in the Wisconsin hosta societies are working hard on putting together a wonderful convention schedule for the weekend of July 7-9th in Madison, Wis. The Madison area is not only beautiful to visit but it is home to some enthusiastic hostaphiles with truly fantastic gar- dens. This convention is within easy driving distance for many of our members who have never treated themselves to a convention. Why not this year? I have a major concern about the lack of response to the need for a local society to host the 2013 and 2014 MRHS conventions. -

AGCBC Seedlist2019booklet

! Alpine Garden Club of British Columbia Seed Exchange 2019 Alpine Garden Club of British Columbia Seed Exchange 2019 We are very grateful to all those members who have made our Seed Exchange possible through donating seeds. The number of donors was significantly down this year, which makes the people who do donate even more precious. We particularly want to thank the new members who donated seed in their first year with the Club. A big thank-you also to those living locally who volunteer so much time and effort to packaging and filling orders. READ THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE FILLING IN THE REQUEST FORM. PLEASE KEEP YOUR SEED LIST, packets will be marked by number only. Return the enclosed request form by mail or, if you have registered to do so, by the on-line form, as soon as possible, but no later than DECEMBER 8. Allocation: Donors may receive up to 60 packets and non-donors 30 packets, limit of one packet of each selection. Donors receive preference for seeds in short supply (USDA will permit no more than 50 packets for those living in the USA). List first choices by number only, in strict numerical order, from left to right on the order form. Enter a sufficient number of second choices in the spaces below, since we may not be able to provide all your first choices. Please print clearly. Please be aware that we have again listed wild collected seed (W) and garden seed (G) of the same species separately, which is more convenient for people ordering on-line. -

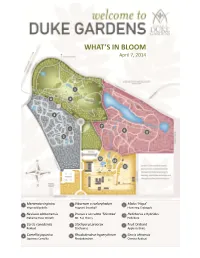

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

These De Doctorat De L'universite Paris-Saclay

NNT : 2016SACLS250 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de doctorat (Biologie) Par Mlle Nour Abdel Samad Titre de la thèse (CARACTERISATION GENETIQUE DU GENRE IRIS EVOLUANT DANS LA MEDITERRANEE ORIENTALE) Thèse présentée et soutenue à « Beyrouth », le « 21/09/2016 » : Composition du Jury : M., Tohmé, Georges CNRS (Liban) Président Mme, Garnatje, Teresa Institut Botànic de Barcelona (Espagne) Rapporteur M., Bacchetta, Gianluigi Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Italie) Rapporteur Mme, Nadot, Sophie Université Paris-Sud (France) Examinateur Mlle, El Chamy, Laure Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Examinateur Mme, Siljak-Yakovlev, Sonja Université Paris-Sud (France) Directeur de thèse Mme, Bou Dagher-Kharrat, Magda Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Co-directeur de thèse UNIVERSITE SAINT-JOSEPH FACULTE DES SCIENCES THESE DE DOCTORAT DISCIPLINE : Sciences de la vie SPÉCIALITÉ : Biologie de la conservation Sujet de la thèse : Caractérisation génétique du genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Présentée par : Nour ABDEL SAMAD Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES Soutenue le 21/09/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Dr. Georges TOHME Président Dr. Teresa GARNATJE Rapporteur Dr. Gianluigi BACCHETTA Rapporteur Dr. Sophie NADOT Examinateur Dr. Laure EL CHAMY Examinateur Dr. Sonja SILJAK-YAKOVLEV Directeur de thèse Dr. Magda BOU DAGHER KHARRAT Directeur de thèse Titre : Caractérisation Génétique du Genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Mots clés : Iris, Oncocyclus, région Est-Méditerranéenne, relations phylogénétiques, status taxonomique. Résumé : Le genre Iris appartient à la famille des L’approche scientifique est basée sur de nombreux Iridacées, il comprend plus de 280 espèces distribuées outils moléculaires et génétiques tels que : l’analyse de à travers l’hémisphère Nord. -

Spring 2014 Cal-Sibe Siblings

Pacific Iris Almanac of the Society for Pacific Coast Native Iris www.pacificcoastiris.org Volume 42 No 2 Spring 2014 Cal-Sibe siblings 'Golden Waves', top, and 'Lyric Laughter', bottom, are sibling Cal-Sibes from the same cross, between a yellow-flowered seedling of I. forrestii and I. innominata. Jean Witt noted that the Siberian parent was a yellow 40 chromosome Siberian seedling, closer in form and color to I. forrestii than to I. wilsonii. The SIGNA Checklist states that the Siberian parent was I. wilsonii. Jean reviewed her notes, and said this is incorrect, it was a forrestii seedling. Year of registration: 1979 for ‗Golden Waves‘, 1988 for ‗Lyric Laughter‘, both by Jean Witt Photographs: Jean Witt Pacific Iris, Almanac of the Society for Pacific Coast Native Iris Volume XXXX1I Number 2 Spring 2014 SPCNI MEMBERSHIP The Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises (SPCNI) is a section of the American Iris Society (AIS). Membership in AIS is recommended but not required for membership in SPCNI. US Overseas Annual, paper $15.00 $18.00 Triennial, paper $40.00 $48.00 Annual, digital $7.00 $7.00 Triennial, digital $19.00 $19.00 Lengthier memberships are no longer available. Please send membership fees to the SPCNI Treasurer. Use Paypal to join SPCNI online at http://pacificcoastiris.org/JoinOnline.htm International currencies accepted IMPORTANT INFORMATION FROM THE SECRETARY/TREASURER ABOUT DUES NOTICES Members who get paper copies, please keep track of the expiration date of your member- ship, which is printed on your Almanac address label. We include a letter with your last issue, and may follow this with an email notice, if you have email. -

AAAAA an Apiary Is Just Being Set up on the Nursery, So We'll Soon Have a Resident Colony of Bees Pollinating Our Plants

AAAAA An Apiary is just being set up on the nursery, so we’ll soon have a resident colony of bees pollinating our plants – as well as supplying us with honey. AIH-1 ACAENA inermis 'Purpurea' 1 litre pot £5.00 Alpine. Mat of unusual amethyst foliage, ruby red in full sun. A62-9 Acaena magellanica subsp. georgiaeaustralis 9 cm pot £4.00 Alpine. One of the very few flowering plants from South Georgia. Rusty brown burrs. AOB-1 Acaena ovalifolia 1 litre pot £6.00 Alpine. Trailing alpine with small flowers followed by burrs of seedheads. US5-9 Acaena saccaticupula SDR7288 9 cm pot £4.00 Alpine. Mat of blue-grey foliage and red/bronze flowers and burrs on short stems. AYY-1 ACHILLEA clavennae SDR5452 1 litre pot £6.00 Alpine. Large flat white flower heads above toothed greyish green leaves. UFQ-1 Achillea falcata 1 litre pot £6.00 Alpine. Flat-topped heads of yellow flowers above silver-grey leaves. U6T-2 Achillea 'Summer Pastels' 2 litre pot £8.00 Herbaceous. Soft flat clusters of flowers in a very wide range of pastels colours. AWF-2 Achillea 'Walter Funcke' 2 litre pot £8.00 Herbaceous. Orange-red flowers over silver-green foliage. LAE-5B ACIS autumnalis AGM 5 bulbs £5.00 Bulb. Autumn snowflake. Small, white, hanging bells. UNB-2 ACONITUM x cammarum 'Bicolor' AGM 2 litre pot £9.00 Herbaceous. Dense clusters of rich blue-and-white monkshood flowers. UCT-2 Aconitum carmichaelii Arendsii Group 2 litre pot £8.00 Herbaceous. Spikes of large, blue, hooded flowers in summer; attractive glossy green leaves. -

Iris Sibirica and Others Iris Albicans Known As Cemetery

Iris Sibirica and others Iris Albicans Known as Cemetery Iris as is planted on Muslim cemeteries. Two different species use this name; the commoner is just a white form of Iris germanica, widespread in the Mediterranean. This is widely available in the horticultural trade under the name of albicans, but it is not true to name. True Iris albicans which we are offering here occurs only in Arabia and Yemen. It is some 60cm tall, with greyish leaves and one to three, strongly and sweetly scented, 9cm flowers. The petals are pure, bone- white. The bracts are pale green. (The commoner interloper is found across the Mediterranean basin and is not entitled to the name, which continues in use however. The wrongly named albicans, has brown, papery bracts, and off-white flowers). Our stock was first found near Sana’a, Yemen and is thriving here, outside, in a sunny, raised bed. Iris Sibirica and others Iris chrysographes Black Form Clumps of narrow, iris-like foliage. Tall sprays of darkest violet to almost black velvety flowers, Jun-Sept. Ht 40cm. Moist, well drained soil. Part shade. Deepest Purple which is virtually indistinguishable from black. Moist soil. Ht. 50cm Iris chrysographes Dykes (William Rickatson Dykes, 1911, China); Section Limniris, Series Sibericae; 14-18" (35-45 cm), B7D; Flowers dark reddish violet with gold streaks in the signal area giving it its name (golden writing); Collected by E. H. Wilson in 1908, in China; The Gardeners' Chronicle 49: 362. 1911. The Curtis's Botanical Magazine. tab. 8433 in 1912, gives the following information along with the color illustration. -

Download This PDF File

Bothalia 41,1: 1–40 (2011) Systematics and biology of the African genus Ferraria (Iridaceae: Irideae) P . GOLDBLATT* and J .C . MANNING** Keywords: Ferraria Burm . ex Mill ., floral biology, Iridaceae, new species, taxonomy, tropical Africa, winter rainfall southern Africa ABSTRACT Following field and herbarium investigation of the subequatorial African and mainly western southern African Ferraria Burm . ex Mill . (Iridaceae: Iridoideae), a genus of cormous geophytes, we recognize 18 species, eight more than were included in the 1979 account of the genus by M .P . de Vos . One of these, F. ovata, based on Moraea ovata Thunb . (1800), was only discovered to be a species of Ferraria in 2001, and three more are the result of our different view of De Vos’s taxonomy . In tropical Africa, F. glutinosa is recircumscribed to include only mid- to late summer-flowering plants, usually with a single basal leaf and with purple to brown flowers often marked with yellow . A second summer-flowering species,F. candelabrum, includes taller plants with several basal leaves . Spring and early summer-flowering plants lacking foliage leaves and with yellow flowers from central Africa are referred toF. spithamea or F. welwitschii respectively . The remaining species are restricted to western southern Africa, an area of winter rainfall and summer drought . We rec- ognize three new species: F. flavaand F. ornata from the sandveld of coastal Namaqualand, and F. parva, which has among the smallest flowers in the genus and is restricted to the Western Cape coastal plain between Ganzekraal and Langrietvlei near Hopefield . Ferraria ornata blooms in May and June in response to the first rains of the season .