From the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi

MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi - MSFAU Journal of Social Sciences Cilt 3 Sayı 20/ Güz 2019 Journal of MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi - MSFAU MSFAU Journal of Social Sciences Cilt 3 Sayı 20/ Güz 2019 Vol 3 Issue 20/ Fall 2019 TARİHSEL SÜREÇ İÇERİSİNDE KENT / THE CITY INSIDE HISTORICAL PROCESS Editoryel Sunuş: Tarihsel Süreç İçerisinde Kent Editorial Introduction: The City Inside Historical Process Ferit Baz Kentleşmenin Kökeni: Mezopotamya’da İlk Kentler The Origins of Urbanization: First Cities in Mesopotamia Nihan Naiboğlu Hellen Polisinin Ortaya Çıkışı: Güncel Çalışmalar Üzerine Değerlendirmeler The Emergence of the Greek Polis: Implications on Current Studies Kenan Eren Augustus’un Anadolu’daki Yapı Politikası The Building Policy of Augustus in Anatolia Mehmet Oktan Kapadokya’daki Hierapolis Kentinden Sıradışı Bir Onurlandırma: Beş Arkhiereus Annesi Bir Kadın An Extraordinary Honor from the City of Hierapolis in Cappadocia: A Woman as a Mother of Five Archiereis Ferit Baz Imparator Zeno Dönemi’nde Cilicia ve Isauria’da Kilise İnşa Faaliyetleri Church Building Activities in Cilicia and Isauria during the Emperor Zeno Period Murat Özyıldırım, Yavuz Yeğin Doğu Avrupa Türk Şehirciliğine Hazar Dönemi’nden Bir Örnek: Mayatsk An Example for the East European Turkish Urbanism from Khazar Period: Mayatsk Özlem Oktay Çerezci Büyük Selçuklular Devrinde Şehirlerin İdaresi Administration of Cities in the Period of the Great Seljuks Nevzat Keleş Oryantalizmi Doğuran İki Başkent: İstanbul – Paris Two Bedrocks of Orientalism: -

SCIAA Archaeologists Excavate Fishing Vessel Christopher F

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Faculty & Staff ubP lications Institute of 6-1992 SCIAA Archaeologists Excavate Fishing Vessel Christopher F. Amer University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sciaa_staffpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in The Goody Bag, Volume 3, Issue 2, 1992, pages 1-2. http://www.cas.sc.edu/sciaa/ © 1992 by The outhS Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Article is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty & Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Goody Bag yOLUME TIIREE. NO.2 SCIM. DMSION OF UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY RJNE 1992 SCIAA ARCHAEOLOGISTS EXCAVATE FISHING VESSEL By Christopher Amer A preliminary examination of the remains of a small wooden ~ diScovered on the foreshore of Hunting Island State Park'was conducted by the Institute's Underwater Archreology Division staff in 1987 after the wreck was exposed by high tides and stonn activity. Since then, the site has continued to deteriorat,e through nonnal wave action, storm activity, and the hands of collectors. The boat's pump tube was removed by a collector during a period when the site was exposed in the winter of 1988-1989. Initial observations led to the conclusion that the wreck is that of a seven meter long (approximately 23 feet) ftshing boat with a "live well. -

I. Uluslararası Akdeniz Sempozyumu 1. International Mediterranean Symposium

I. Uluslararası Akdeniz Sempozyumu 1. International Mediterranean Symposium BİLDİRİ TAM METİNLERİ KİTABI SYMPOSIUM FULL TEXT BOOK CİLT 6 / VOLUME 6 EDİTÖR Prof. Dr. Durmuş Ali ARSLAN Editör Yardımcıları Gülten ARSLAN Halil ÇAKIR MERSİN I. ULUSLARARASI AKDENİZ SEMPOZYUMU / 1. International Mediterranean Symposium I. Uluslararası Akdeniz Sempozyumu 1. International Mediterranean Symposium BİLDİRİ TAM METİNLERİ KİTABI SYMPOSIUM FULL TEXT BOOK CİLT 6 / VOLUME 6 Editör: Prof. Dr. D. Ali ARSLAN Editör Yardımcısı: Gülten ARSLAN Halil ÇAKIR Kapak Tasarımı: Prof. Dr. D. Ali ARSLAN Mizanpaj-Ofset Hazırlık: Prof. Dr. D. Ali ARSLAN © Mer Ak Yayınları 2018 – Mersin ISBN: 978-605-81003-5-0 Mer-Ak Mersin Akademi Yayınları Adres: Çiftlikköy Mahallesi, 34. Cadde, Nisa 1 Evleri, No: 35, 6/12, Yenişehir/MERSİN Tel: 0532 270 81 45 / 0553 666 06 06 Not: Bölümlerin her türlü idari, akademik ve hukuki sorumluluğu yazarlarına aittir. 1 I. ULUSLARARASI AKDENİZ SEMPOZYUMU / 1. International Mediterranean Symposium Önsöz Çok Değerli Bilim İnsanları ve Kıymetli Araştırmacılar, Her yıl periyodik olarak düzenlenmesi planlanan Uluslararası Akdeniz Sempozyumu’nun ilki, 1-3 Kasım 2018 tarihleri arasında Mersin’de, Mersin Üniversitesi ve Mersin Akademi Danışmanlık iş birliği ile gerçekleştirildi. Özelde Akdeniz Bölgesi illeri (Adana, Antalya, Burdur, Hatay, Isparta, Kahramanmaraş, Mersin, Osmaniye dâhil) ile bu illerimizin ilçeleri ve her türlü yerleşim birimlerini ele alan, genelde ise aşağıdaki alanlara giren her türlü bilimsel araştırma ve akademik çalışmaya sempozyum -

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3Rd July 2020 Daily Timetable

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3rd July 2020 Daily Timetable Before 9am Wake up 9am PE with The Body Coach Please complete the activities in your home learning books. 9.30am Maths Quiz TTRS Battle Email [email protected] if 10.30am Saturn V Titan you have any questions about Jupiter V Neptune the home learning and we will try to get back to you as soon 11am Break as possible. 11.15am Continue Writing Challenge Please email some home SPAG Activity learning you are proud of each week. We love seeing what you 12pm Lunch and time to play are getting up to. 1pm Reading for Pleasure 1.30pm Inquiry Challenge PE Challenge Here is your weekly PE challenge or activity to do which focuses on PE skills such as, agility, balance and co-ordination. Have a go during your morning break! Click here for the PE Challenge Maths Quiz 1. What time is being shown on 2. the clock? 3. 4. 5. The film Artic Adventures starts at 10:20am and finishes at 12:50pm. How long dies the film last? ____ hours ____ minutes 6. 8. 7. Nijah has football practice at 16:10. It last 45 minutes. What time does it finish? Maths Quiz Answers 3. 1. a) 5:20 or 20 minutes past 5 b) 5:40 or 20 minutes to 6 2. 4. a) 25 minutes 5. 2 hours 30 minutes 6. Both could be correct because we don’t know if the race started at 3.30am or 3.30pm. -

Roma Dönemi Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Ticaretinde Kiyi Kilikya Bölgesi'nin Yeri Ve Önemi

T.C. SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ARKEOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI KLASİK ARKEOLOJİ BİLİM DALI ROMA DÖNEMİ DOĞU AKDENİZ DENİZ TİCARETİNDE KIYI KİLİKYA BÖLGESİ’NİN YERİ VE ÖNEMİ AHMET BİLİR DOKTORA TEZİ Danışman YRD. DOÇ. DR. MEHMET TEKOCAK Konya 2014 II T. C. SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü Bilimsel Etik Sayfası Adı Soyadı Ahmet Bilir Numarası 104103011001 Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Arkeoloji / Klasik Arkeoloji Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans Doktora Öğrencinin Roma Dönemi Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Ticaretinde Tezin Adı Kıyı Kilikya Bölgesi’nin Yeri Ve Önemi Bu tezin proje safhasından sonuçlanmasına kadarki bütün süreçlerde bilimsel etiğe ve akademik kurallara özenle riayet edildiğini, tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu, ayrıca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada başkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atıf yapıldığını bildiririm. Öğrencinin imzası (İmza) III T. C. SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü Doktora Tezi Kabul Formu Adı Soyadı Ahmet Bilir Numarası 104103011001 Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Arkeoloji / Klasik Arkeoloji Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans Doktora Yrd. Doç. Dr. Mehmet Tekocak Tez Danışmanı Öğrencinin Roma Dönemi Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Ticaretinde Tezin Adı Kıyı Kilikya Bölgesi’nin Yeri Ve Önemi Yukarıda adı geçen öğrenci tarafından hazırlanan Roma Dönemi Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Ticaretinde Kıyı Kilikya Bölgesi’nin Yeri Ve Önemi Yeri başlıklı bu çalışma ……../……../…….. tarihinde yapılan savunma sınavı sonu- cunda oybirliği/oyçokluğu ile başarılı bulunarak, jürimiz tarafından yüksek lisans tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. Ünvanı, Adı Soyadı Danışman ve Üyeler İmza IV Önsöz Geriye dönüp bakınca hep üniversite yılları, kazılar, bölümün koridorları, dostluklar ve hocalar akla geliyor. Bu süre zarfında hissettiğim duygunun bir tarifi olarak aile sıcaklığı kavramını yakıştırabilirim. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 058 SE 012 062 AUTHOR Kohn, Raymond F. Environmental Education, the Last Measure of Man. an Anthology Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 058 SE 012 062 AUTHOR Kohn, Raymond F. TITLE Environmental Education, The Last Measure of Man. An Anthology of Papers for the Consideration of the 14th and 15th Conference of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO. INSTITUTION National Commission for UNESCO (Dept. of State), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 199p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Anthologies, *Ecology, *Environment, EnVironmental Education, Environmental Influences, *Essays, *Human Engineering, Interaction, Pollution IDENTIFIERS Unesco ABSTRACT An anthology of papers for consideration by delegates to the 14th and 15th conferences of the United States National Commission for UNESCO are presented in this book. As a wide-ranging collection of ideas, it is intended to serve as background materials for the conference theme - our responsibility for preserving and defending a human environment that permits the full growth of man, physical, cultural, and social. Thirty-four essays are contributed by prominent authors, educators, historians, ecologists, biologists, anthropologists, architects, editors, and others. Subjects deal with the many facets of ecology and the environment; causes, effects, and interactions with man which have led to the crises of today. They look at what is happening to man's "inside environment" in contrast to the physical or outside environment as it pertains to pollution of the air, water, and land. For the common good of preserving the only means for man's survival, the need for world cooperation and understanding is emphatically expressed. (BL) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. -

![TBRC-17 [Bulk Freighters]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9949/tbrc-17-bulk-freighters-489949.webp)

TBRC-17 [Bulk Freighters]

[TBRC-17: Bulk Finding Aid: C. Patrick Labadie Collections Freighters] Collection name: C. Patrick Labadie Collection Collection number: TBRC -1 through 18 [TBRC-17 = BULK FREIGHTERS] Dates: Late 18th Century to early 20th Century. Quantity: 385 linear feet + 6 (5 draw) map cabinets. Provenance note: Collection gathered & researched since early adulthood. Donated by C. Patrick & June Labadie in 2003 to NOAA; housed and managed by the Alpena County Library. Biographical & Historical Information: The son and grandson of shipyard workers, Charles Patrick Labadie was reared in Detroit and attended the University of Detroit. He began his career with the Dossin Great Lakes Museum, became director of the Saugatuck Marine Museum, then earned a master’s license for tugs and worked for Gaelic Tugboat Company in Detroit. He directed Duluth’s Canal Park Museum (now Lake Superior Maritime Visitors Center) from its founding in 1973 until 2001. In 2003, he was appointed historian for the NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Alpena, Michigan. Scope & Content: This is an extensive 19th Century Great Lakes maritime history collection. The vessel database is accessible through library’s website. See the library’s card catalog to search the book collection. The major components of the collection are: vessels, cargo, biographical, canals, owners, ports, technology / shipbuilding = broken down by vessels types (i.e. sail, tugs, propellers), and machinery. Files include photographs, newspaper accounts, publications, vessel plans, maps & charts, and research notes. Access: Open to research. Preferred Citation: C. Patrick Labadie Collection, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, Alpena, MI. [TBRC-17: Bulk Finding Aid: C. Patrick Labadie Collections Freighters] Contents: TBRC-17: TECHNICAL – BULK FREIGHTERS Box 1: Folders 1. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service WAV 141990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cobscook Area Coastal Prehistoric Sites_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ' • The Ceramic Period; . -: .'.'. •'• •'- ;'.-/>.?'y^-^:^::^ .='________________________ Suscruehanna Tradition _________________________ C. Geographical Data See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in j£6 CFR Part 8Q^rjd th$-§ecretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. ^"-*^^^ ~^~ I Signature"W"e5rtifying official Maine Historic Preservation O ssion State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this -

Biology and Management of Fish Stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wageningen University & Research Publications Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Promotor: dr. E.A. Huisman, Hoogleraar in de Visteelt en Visserij Co-promotor: dr. ir. M.A.M. Machiels Universitair docent bij leerstoelgroep Visteelt en Visserij Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van de Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, dr. C.M. Karssen, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 22 juni 1998 des namiddags te half twee in de Aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen. Cover : Traditional fishing with reed boat and a motorised fishing boat (back-cover) on Lake Tana. Photo: Courtesy Interchurch Foundation Ethiopia/Eritrea (ISEE), Urk, the Netherlands. Cover design: Wim Valen. Printing: Grafisch Service Centrum Van Gils b.v., Wageningen CIP-DATA KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Wudneh, Tesfaye Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia / Tesfaye Wudneh. - [S.I. : s.n.]. - III. Thesis Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen. - With ref. - With summary in Dutch. ISBN 90-5485-886-9 Tesfaye Wudneh 1998. Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. The biology of the fish stocks of the major species in the Bahir Dar Gulf of Lake Tana, the largest lake in Ethiopia, has been studied based on data collected during August 1990 to September 1993. The distribution, reproduction patterns, growth and mortality dynamics and gillnet selectivity of these stocks are described. -

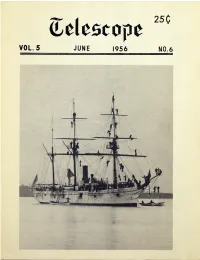

VOL. 5 JUNE 1956 N0.6 W T I T B T a P T PUBLISHED BY

( L d e s c o p e 2 5 0 VOL. 5 JUNE 1956 N0.6 W t i t B t a p t PUBLISHED BY G r eat L a k e s M o d e l S hipbuilders ' G u il d J. E. JOHNSTON, 54Q1 Woodward Avenue R- H DAVISON, E d ito r:____ Detro.t 2> Michigan — Associate_Editor Membership $3.00 Subscription $2.50 Supported in part by the Detroit Historical Society EDITORIAL Cooperation is the key to whatever success we have achieved in our effort to preserve the history of Great Lakes commervial shipping. There have been so many examples of good cooperation, within the past month, it might be well to mention it here. The U.S.Naval Reserve, Chicago office, came up with plans and photo graphs of the "Willmette", ex "Eastland”. The brothers, Frank and Robt. Kuhn, dropped in at the museum with a lot of good leads, and the sheets from the plans of the "Virginia" which are missing from our set. Mr.Wil- liam McDonald sent in the histories of the steamers shown on the last pages of this issue. Mr.Dexter Goodison, of Erieau, Ontario, presented us with the plans of a modern, welded-steel gill netter. Frank Slyker brought in his completed plans of the U.S.Michigan (later the gunboat "Wolverine"). The American Shipbuilding sent us the plans of the flat top "Wolverine" which was formerly the "Seeandbee". All this is very gratifying, and confirms our belief that through regional cooperation there is hardly any end to what we may achieve in the field of Creat Lakes history. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

International Erdemli Symposium Abstract Book 19-21 April 2018 Editors Asst

International Erdemli Symposium Abstract Book 19-21 April 2018 Editors Asst. Prof. Dr. Bünyamin DEMİR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selma ERAT Prof. Dr. Murat YAKAR International Erdemli Symposium was held on April 19-21, 2018 in Mersin Province Erdemli District. Erdemli is the 6th largest district of the Mersin Province and is at the forefront with its large and deep history, rich cultural accumulation, unique natural beauties, springs, historical sites and important agricultural facilities. It is thought that there are many issues that need to be produced and evaluated about Erdemli, which continues to develop and grow, at present and in future. For this purpose, it was aimed to create an awareness of ideas and project proposals about Erdemli to be discussed in a scientific atmosphere and to share it with public. In addition to that, this symposium could be a platform in which business or research relations for future collaborations will be established. International Erdemli symposium has received quite high interests from academician sides. We had in total 350 presentations from different universities. The symposium was organized in Erdemli by Mersin University with collaboration of municipality of Erdemli for the first time and internationally and free of charge. We believe that the symposium will be beneficial to our city Mersin and our country Turkey. As organizing committee, we believe that we had a successful symposium. We gratefully thank to the scientific committee of the symposium, all of the speakers, all of the participants, all of the students, all of the guests and also the press members for their contributions. On behalf of the organizing committee.