SIR HAMILTON HARTY Piano By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View the Concert Programme

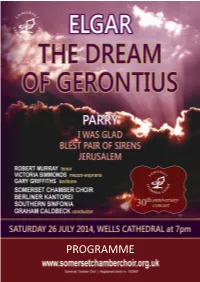

PROGRAMME Happy birthday Somerset Chamber Choir! Welcome to our 30th birthday party! We are delighted that our very special invited guests, our loyal choir ‘Friends’ and everyone here tonight could join us for this occasion. As if that weren’t enough of a nucleus for a wonderful party, the BERLINER KANTOREI have travelled from Berlin to celebrate with us too ... their ‘return match’ for an excellent time some of us enjoyed singing with them when they hosted us last autumn. This concert comes at the end of a week which their party of singers and supporters have spent staying in and sampling the delights of Somerset; we hope their experience has been a memorable one and we wish them bon voyage for their journey home. Ten years of singing together in the 1970s and 1980s under the inspirational direction of the late W. Robert Tullett, founder conductor of the Somerset Youth Choir, welded a disparate group of young people drawn from schools across Somerset, into a close-knit group of friends who had discovered the huge pleasure of making music together and who developed a passion for choral music that they wanted to share. The Somerset Chamber Choir was founded in 1984 when several members who had become too old to be classed as “youths” left the Youth Choir and, with the approval of Somerset County Council, drew together other like-minded singers from around the County. Blessed with a variety of complementary skills, a small steering group set about developing a balanced choir and appointed a conductor, accompanist and management team. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

Yorkshire & North East Branch Newsletter No

Yorkshire & North East Branch Newsletter No 20 - April 2021 Edited by Paul Kampen - [email protected] 74 Springfield Road, Baildon, Shipley, W.Yorks BD17 5LX 01274 581051 Branch Chairman’s message n view of the significance for Elgar of that delightful perennial, the anemone nemorosa, we can all take hope from our first sighting of the windflower, not only that spring has Iarrived but that the various restrictions which society has been forced to endure are gradually being lifted. As the politicians are fond of reminding us: it’s been a challenging year. Here at the Yorkshire & North East branch we have met the challenge in various ways. Most importantly, we have maintained our programme of talks, almost without interruption, by means of that technological miracle, the remote electronic platforms, especially Zoom. We took a degree of satisfaction in being the first branch to embrace the technology when, in May 2020, Christopher Wiltshire gave his trailblazing presentation, followed by Stuart Freed (June), Peter Newble (September, via Vimeo), Bernard Porter (November), and Steven Halls (March). We are extremely grateful to all these speakers not only for rising to the technological challenge but for such highly informative and enjoyable occasions, and we look forward to more on-line meetings in April, May and June. By the time of our scheduled meeting in September, we should be out of lockdown and back at our home, the Bar Convent, York. But this raises an important question: do we continue as before, as if nothing had happened, or do we learn from the experience and modify our operations? Let us not forget that Zoom meetings have attracted a wider audience than those at the Bar Convent. -

Winter Journey’) (1827) (Arr

JohannSCHUBERT Sebastian WinterBACH Journey MagnaTrombone Sequentia Travels•1 II A Grand Suite of Dances compiled and performed by Sonia Rubinsky, Piano Matthew Gee, Trombone Christopher Glynn, Piano Trombone Travels • 1 consumes him. A Will-o’-the-wisp lures the wanderer ‘Into as he claims to be ‘finished with all dreams’. The end of this Franz Schubert (1797–1828) the deepest rocky chasms’. Wide intervals and a playful long night is signalled by a Stormy Morning, with its florid, Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 (‘Winter Journey’) (1827) (arr. Matthew Gee, b. 1982) vocal line reflect the twists and turns of his journey, until punchy piano writing and symphonic vocal line – ‘How the anguish at the final turn – ‘Every river will reach the sea … storm has torn apart / The grey mantle of the sky!’ This is The trombone is praised for its vocal qualities. Its facility to is a huge challenge – subtle textual changes are Every sorrow, too, will reach its grave’. The weary fugitive truly idiomatic trombone writing. The storm passes quickly glissando allows it to directly mimic vocal techniques – emphasised by an octave shift in the second verse and cup then finds Rest ‘In a charcoal-burner’s cramped cottage’. and is replaced by a lilting dance as the wanderer follows a vibrato, portamento and all manner of microtonal inflections. mute in the last. Unusually, the sudden major key final verse Exhausted, he revels in the turbulence within his heart. light ‘this way and that’. On the surface a very sweet song, The player can develop colours further by altering the vowel offers no hope: the wanderer writes ‘Good night’ on her gate Quick dynamic changes – hushed moans and sorrowful but bestowed a poignant twist through its title, A Mirage. -

Vol. 13, No.2 July 2003

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • T Snow • Fly, Singing Birdournal • From the Bavarian Highlands • The of Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George Deum and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Origina Theme (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson Matin • Three Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius Serenade Lyrique • Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May S Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduct and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wan Youth • How Calmly the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is t Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • So The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlig Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fring the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • ViolinJULY Sonata 2003 Vol.13, in E minor No.2 • Strin Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 24,1904-1905, Trip

THE LYRIC, BALTIMORE. BostonSymptionuOicfiesti; Mr. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. Twenty-fourth Season, J904-J905. PROGRAMME OF THE THIRD CONCERT TUESDAY EVENING, JANUARY 10, AT 8.15 PRECISELY. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by Philip Hale* Published by C. A. ELUS, Manager. l THE MAKERS OF THESE INSTRUMENTS have shown that genius for pianoforte making that has been defined as "an infinite capacity for taking pains." The result of eighty years of application of this genius to the production of musical tone is shown in the Chickering of to-day. Catalogue upon Application CHICKERING & SONS 79J Tfemont Sireei. Boston. REPRESENTED IN BALTIMORE BY KRANZ-SMITH PIANO COMPANY Boston The Lyric, Mount Royal and ty ^VlTinhnnV "W" Maryland Avenues, ^^IIipiIUIlJ S. Baltimore. l^tt/v tlAgi' fgl Twenty-fourth Season, J904-J905. V-rl C'llt^LlCl Twentieth Season in Baltimore. Mr. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. THIRD CONCERT, TUESDAY EVENING, JANUARY 10, AT 8.15 PRECISELY. PROGRAMME. Beethoven .... Symphony No. 5, in C minor, Op. 67 I. Allegro con brio. II. Andante con moto. III. Allegro: Trio. IV. Allegro. " " Bruch . Penelope's Recitative and Prayer from Odysseus Brahms .......... Waltzes (Orchestrated by W. Gericke.) Edward Elgar . " Sea Pictures," Three Songs from a Cycle of Five for Contralto and Orchestra, Op. 37 " Wagner ..... Overture to " The Flying Dutchman SOLOIST: Miss MURIEL FOSTER. There wjll be aa intermission of ten minutes after the Bruch selection. 3 THE Musicians Library No contemporary venture in music publishing is fraught with more interest to lovers of the art than the Musicians Library, issued by the Oliver Ditson Company. The volumes already in hand show conscientious adherence to high musical ideals. -

Roger Quilter

ROGER QUILTER 1877-1953 HIS LIFE, TIMES AND MUSIC by VALERIE GAIL LANGFIELD A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham February 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Roger Quilter is best known for his elegant and refined songs, which are rooted in late Victorian parlour-song, and are staples of the English artsong repertoire. This thesis has two aims: to explore his output beyond the canon of about twenty-five songs which overshadows the rest of his work; and to counter an often disparaging view of his music, arising from his refusal to work in large-scale forms, the polished assurance of his work, and his education other than in an English musical establishment. These aims are achieved by presenting biographical material, which places him in his social and musical context as a wealthy, upper-class, Edwardian gentleman composer, followed by an examination of his music. Various aspects of his solo and partsong œuvre are considered; his incidental music for the play Where the Rainbow Ends and its contribution to the play’s West End success are examined fully; a chapter on his light opera sheds light on his collaborative working practices, and traces the development of the several versions of the work; and his piano, instrumental and orchestral works are discussed within their function as light music. -

Vol. 15, No. 3 November 2007

Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • HowElgar Calmly Society the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No.2 •ournal O Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Violin Sonata in E minor • String Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wanderer • Empire March • The Herald • Beau Brummel • Severn Suite • Soliloquy • Nursery Suite • Adieu • Organ Sonata • Mina • The Spanish Lady • Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Gavotte • Salut d'Amour • Mot d'Amour • Bizarrerie • O Happy Eyes • My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • The Snow • Fly, Singing Bird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The Light of LifeNOVEMBER • King Olaf2007 Vol.• Imperial 15, No. -

Lionel Tertis, York Bowen, and the Rise of the Viola

THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by WILLIAM KENTON LANIER B.A., Thomas Edison State University, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 WILLIAM KENTON LANIER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND William Kenton Lanier, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree in Musicology University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT The viola owes its current reputation largely to the tireless efforts of Lionel Tertis (1876-1975), who, perhaps more than any other individual, brought the viola to light as a solo instrument. Prior to the twentieth century, numerous composers are known to have played the viola, and some even preferred it, but none possessed the drive or saw the necessity to establish it as an equal solo counterpart to the violin or cello. Likewise, no performer before Tertis had established themselves as a renowned exponent of the viola. Tertis made it his life’s work to bring the viola to the fore, and his musical prowess and technical ability on the instrument gave him the tools to succeed. Tertis was primarily a performer, thus collaboration with composers also comprised a necessary element of his viola crusade. He commissioned works from several British composers, including one of the first and most prolific composers for the viola, York Bowen (1884-1961). -

I Muse and Method in the Songs of Hamilton Harty

Muse and Method in the Songs of Hamilton Harty: Three Early Works, 1895–1913 Judith Carpenter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2017 Sydney, Australia i This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mother. To an Athlete Dying Young A. E. HOUSMAN The time you won your town the race We chaired you through the market-place; Man and boy stood cheering by, And home we brought you shoulder-high. Today, the road all runners come, Shoulder-high we bring you home, And set you at your threshold down, Townsman of a stiller town. Smart lad, to slip betimes away From fields where glory does not stay, And early though the laurel grows It withers quicker than the rose. Eyes the shady night has shut Cannot see the record cut, And silence sounds no worse than cheers After earth has stopped the ears. Now you will not swell the rout Of lads that wore their honours out, Runners whom renown outran And the name died before the man. So set, before its echoes fade, The fleet foot on the sill of shade, And hold to the low lintel up The still-defended challenge-cup. And round that early-laurelled head Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead, And find unwithered on its curls The garland briefer than a girl’s. ii iii Contents Preface........................................................................................................................... vi Abstract .........................................................................................................................