Vol. 13, No. 1 March 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

To View the Concert Programme

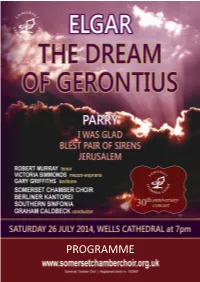

PROGRAMME Happy birthday Somerset Chamber Choir! Welcome to our 30th birthday party! We are delighted that our very special invited guests, our loyal choir ‘Friends’ and everyone here tonight could join us for this occasion. As if that weren’t enough of a nucleus for a wonderful party, the BERLINER KANTOREI have travelled from Berlin to celebrate with us too ... their ‘return match’ for an excellent time some of us enjoyed singing with them when they hosted us last autumn. This concert comes at the end of a week which their party of singers and supporters have spent staying in and sampling the delights of Somerset; we hope their experience has been a memorable one and we wish them bon voyage for their journey home. Ten years of singing together in the 1970s and 1980s under the inspirational direction of the late W. Robert Tullett, founder conductor of the Somerset Youth Choir, welded a disparate group of young people drawn from schools across Somerset, into a close-knit group of friends who had discovered the huge pleasure of making music together and who developed a passion for choral music that they wanted to share. The Somerset Chamber Choir was founded in 1984 when several members who had become too old to be classed as “youths” left the Youth Choir and, with the approval of Somerset County Council, drew together other like-minded singers from around the County. Blessed with a variety of complementary skills, a small steering group set about developing a balanced choir and appointed a conductor, accompanist and management team. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

Download Booklet

A KNIGHT’S PROGRESS A KNIGHT’S PROGRESS According to the rubric in the service book for the 1953 Coronation, the Queen, as soon as 1 I was glad Hubert Parry (1848-1918) [4.57] Born in the seaside town of Bournemouth, Sir she entered at the west door of the Church, 2 The Twelve William Walton (1902-1983) [11.49] Charles Hubert Hastings Parry went on to study was to be received with this anthem and, while Soloists: Oscar Simms treble at Eton and then at Oxford University where it was being sung, she was to pass through Benedict Davies treble Tom Williams alto he subsequently became Professor of Music. the body of the Church, into and through the Thomas Guthrie tenor From 1895 until his death he was also Director Choir, and up to her Chair of Estate beside Christopher Dixon bass of the Royal College of Music in London. He the Altar. On that occasion the Queen’s Our present charter * Nico Muhly (b.1981) wrote music of all kinds, including an opera, Scholars of Westminster School led the choir 3 I. First [4.02] symphonies, chamber and instrumental music, in singing the central section of this anthem – 4 II. Thy Kingdome Come, O God [4.21] oratorios and church music. However, he is ‘Vivat Regina Elizabetha!’ – a section that 5 III. The Beatitudes [4.22] perhaps best known nowadays for his famous nowadays is ususally omitted in concert 6 IV. Nullus Liber Homo Capiatur [4.45] setting of William Blake’s poem, Jerusalem. performances, as it is on this recording. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct phnt, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthonzed copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion Oversize materials (e g . maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMl® UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MICHAEL HEAD’S LIGHT OPERA, KEY MONEY A MUSICAL DRAMATURGY A Document SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARILYN S. GOVICH Norman. Oklahoma 2002 UMl Number: 3070639 Copyright 2002 by Govlch, Marilyn S. All rights reserved. UMl UMl Microform 3070639 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17. United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

Choir of St John's College, Cambridge Andrew Nethsingha

Choir of St John’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE ANDREW NETHSINGHA Felix Mendelssohn, 1847 Mendelssohn, Felix Painting by Wilhelm Hensel (1794 – 1861) / AKG Images, London The Call: More Choral Classics from St John’s John Ireland (1879 – 1962) 1 Greater Love hath no man* 6:02 Motet for Treble, Baritone, Chorus, and Organ Alexander Tomkinson treble Augustus Perkins Ray bass-baritone Moderato – Poco più moto – Tempo I – Con moto – Meno mosso Douglas Guest (1916 – 1996) 2 For the Fallen 1:21 No. 1 from Two Anthems for Remembrance for Unaccompanied Chorus Slow Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848 – 1918) 3 My soul, there is a country 4:00 No. 1 from Songs of Farewell, Six Motets for Unaccompanied Chorus Slow – Daintily – Slower – Animato – Slower – Tempo – Animato – Slower – Slower 3 Roxanna Panufnik (b. 1968) 4 The Call† 4:21 for Chorus and Harp For Andrew Nethsingha and the Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Hear my prayer* 11:21 Hymn for Solo Soprano, Chorus, and Organ Wilhelm Taubert gewidmet Oliver Brown treble 5 ‘Hear my prayer’. Andante – Allegro moderato – Recitativ – Sostenuto – 5:51 6 ‘O for the wings of a dove’. Con un poco più di moto 5:29 Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry 7 I was glad* 5:28 Coronation Anthem for Edward VII for Chorus and Organ Revised for George V Maestoso – Slower – Alla marcia 4 Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 – 1924) 8 Beati quorum via 3:39 No. 3 from Three [Latin] Motets, Op. 38 for Unaccompanied Chorus To Alan Gray and the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge Con moto tranquillo ma non troppo lento Sir John Tavener (1944 – 2013) 9 Song for Athene 5:31 for Unaccompanied Chorus Very tender, with great inner stillness and serenity – With resplendent joy in the Resurrection Sir Charles Villiers Stanford 10 Te Deum laudamus* 6:47 in B flat major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeur from Morning, Communion, and Evening Services, Op. -

Beecham: the Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13

April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Journal The DeliusDe/ius Society Journal + .---- April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Full Membership £8.00t8.00 per year Students £5.0095.00 Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) £6.00f,6.00 per year USA and Canada US $17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus,D Mus,Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson M Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford Robinson OBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith Davies MA, BMus,B Mus,FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon DMusD Mus VemonVernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) ChairmanChairmart RBR B Meadows 5 Westbourne House, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 Wishing Tree Road, S1.St. Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 5053750537 Membership Secretary Miss Estelle Palmley 22 Kingsbury Road, Colindale,Cotindale,London NW9 ORR Editor Stephen Lloyd 414l Marlborough Road, Luton, Bedfordshire LU3 lEFIEF Tel: Luton (0582)(0582\ 20075 2 CONTENTS Editorial...Editorial.. 3 Music Review ... 6 Jelka Delius: a talk by Eric Fenby 7 Beecham: The Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13 Gordon Clinton: a Midlands Branch meeting 20 Correspondence 22 Forthcoming Events 23 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketch of Delius by Edvard Munch reproduced by kind permission of the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The quotation from In a Summer GardenGuden on page 7 is in the arrangement by Philip Heseltine included in the volume of four piano transcriptions reviewed in this issue and appears with acknowledgement to Thames Publishing and the Delius Trust. -

R,Eg En T's S.10411415 Wood -P P

R,EG EN T'S S.10411415 WOOD -P P o AAYLLOONt \\''. 4k( ?(' 41110ADCASTI -PADDINGTON "9' \ \ - s. www.americanradiohistory.com St l'ANCRAS U S TON \ 4\ \-4 A D RUSSEL. A. 'G,PORTLAND St \ O \ \ L. \ \2\\\ \ SQUARE \ l' \ t' GOO DGT. 1,..\ S , ss \ ' 11 \ \ \ 4-10USi \ç\\ NV cY\6 \ \ \ e \ """i \ .jP / / ert TOTT E N NAM // / ;COI COURT N.O. \ ON D ).7"'";' ,sr. \,60 \-:Z \COvtroi\ oA ARDEN O \ www.americanradiohistory.com X- www.americanradiohistory.com THE B. B. C. YEAR=BOOK 1 93 3 The Programme Year covered by this book is from November I, 1931 to October 31, 1932 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION BROADCASTING HOUSE LONDON W I www.americanradiohistory.com f Readers unfamiliar with broadcasting will find it easier to understand the articles in this book if they bear in mind the following :- (I) The words "Simultaneous(ly) Broadcast" or "S.B." refer to the linking of two or more transmitters by telephone lines for the purpose of broadcasting the same programme ; e.g. the News Bulletins are S.B. from all B.B.C. Stations. (2) The words "Outside Broadcast" or "O.B." refer to a broadcast outside the B.B.C. studios, not necessarily out -of- doors; e.g. a concert in the Queen's Hall or the commentary on the Derby are equally outside broadcasts. (3) The B.B.C. organisation consists, roughly speaking, of a Head Office and five provincial Regions- Midland Region, North Region, Scottish Region, West Region, and Belfast. The Head Office includes the administration of a sixth Region - the London Region-which supplies the National programme as well as the London Regional programme. -

Werner Alberti Jerzy S. Adamczewski Martin Abendroth Bessie Abott

Martin Abendroth Sinfonie Orchester, dir. Felix Günther Die Zauberflöte Mozart 1929, Berlín 52434 In diesen heiligen Hallen Hom. A 8030 5101 52435 O Isis und Osiris Hom. A 8030 5101 Bessie Abott, Enrico Caruso, Louise Homer, Antonio Scotti orchestra Rigoletto Verdi 20.2.1907, New York A 4259 Bella figlia dell´amore HMV DO 100 6823 Jerzy S. Adamczewski Orkiestra symfoniczna, dir. Olgierd Straszyński Halka Stanisław Moniuszko / Włodzimierz Wołski 1955±, Varšava WA 1489 Racitativ i ariaJanusza Muza 1717 P 1321 Auguste Affre, Etienne Billot Orchestre Faust Gounod x.5.1907, Paříž XP 3362 Duo du 1er Acte – 2 Disque Odeon 60329 X 40 Werner Alberti klavír Martha Flotow x.9.1905, Berlín xB 675 Mag der Himmel euch vergeben Odeon Record 34296, 1/10 okraj X 15 Postillion von Lonjumeau Adam x.9.1905, Berlín Bx 679 Postillionslied Odeon Record 34296, 1/10 okraj X 15 Orchester Troubadour Verdi x.2.1906, Berlín 1001 Ständchen Hom. B. 838 P 11261 14.5.1906, Berlín 1701 Stretta Hom. B. 838 P 11261 Bajazzo Leoncavallo x.7.1912, Berlín 14281 Nein, bin Bajazzo nichr bloss! Beka B. 3563 P 10964 14285 Hüll´ dich in Tand Beka B. 3563 P 10964 Odeon-Orchester, dir. Friedrich Kark Troubadour Verdi x.9.1906, Berlín Bx 1641 Ständchen Odeon Record 50152 X 65 Lohengrin Wagner x.9.1906, Berlín Bx 1659 Nun sei bedankt, mein lieber Schwann Odeon Record 50161 X 65 Frances Alda, Enrico Caruso, Josephine Jacoby, Marcel Journet Victor Orchestra, dir. Walter B. Rogers Martha Flotow 7.1.1912, New York A 11437 Siam giunti, o giovinette HMV DM 100 5420 A 11438 Che vuol dir cio HMV DM 100 5420 A 11439 Presto, presto andiam HMV DM 104 5422 A 11440 T´ho raggiunta sciagurata HMV DM 104 5422 Frances Alda, Enrico Caruso, Marcel Journet Victor Orchestra, dir.