Leconte EF 2020 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Panama Cannonball's Transnational Ties: Migrants, Sport

PUTNAM: THE PANAMA CANNONBALL’S TRANSNATIONAL TIES The Panama Cannonball’s Transnational Ties: Migrants, Sport, and Belonging in the Interwar Greater Caribbean LARA PUTNAM† Department of History University of Pittsburgh The interwar years saw the creation of a circum-Caribbean migratory sphere, linking British colonial sending societies like Jamaica and Barbados to receiving societies from Panama to Cuba to the Dominican Republic to the United States. The overlapping circulation of migrants and media created transnational social fields within which sport practice and sport fandom helped build face-to-face and imagined communities alike. For the several hundred thousand British Caribbean emigrants and their children who by the late 1920s resided abroad, cricket and boxing were especially central. The study of sport among interwar British Caribbean migrants reveals overlapping transnational ties that created microcultures of sporting excellence. In this mobile and interconnected world, sport became a critical realm for the expression of nested loyalties to parish, to class, to island, to empire, and to the collective they called “Our People,” that is, “the Negro Race,” worldwide. †The author is grateful to Rob Ruck, Theresa Runstedtler, and three anonymous reviewers for the Journal of Sport History for very helpful comments on earlier versions. Correspondence to [email protected]. Fall 2014 401 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY THE PANAMA AMERICAN’S “WEST INDIAN PAGE” in August of 1926 traced a world of sports in motion. There was a challenge from -

Genius with the Samba Beat: Golden Bantam Eder Jofre Was the Complete Fighter

Genius with the Samba beat: Golden bantam Eder Jofre was the complete fighter By Mike Casey When it finally happened, nobody could quite believe it. Eder Jofre had been beaten. It didn’t seem possible and people had begun to wonder if it was even allowed. Far from the sun-kissed shores of his native Brazil, before 12,000 wildly cheering Japanese fans at the Aichi Prefectural Gym in Nagoya, the masterful genius of a boxer who could do it all had lost his bantamweight championship to the perpetual little buzzsaw that was Masahiko ‘Fighting’ Harada. News of such cataclysmic events took an age to trickle through to the average boxing fan in the stark and simpler days of 1965. There was no Internet, no twenty-four hour news stations and no mention of boxing on the TV or radio unless Muhammad Ali had done something else to ruffle the feathers of the silent majority. When I finally saw the result in the newspaper, tucked away at the bottom of the page in the form of a two-liner, I seriously wondered if the sub-editor had lunched for a little too long at his favourite watering hole and accidentally transposed the names. Nobody expected Eder Jofre to lose to Fighting Harada, because Jofre was a genuine wonder of a fighter who didn’t lose to anyone. Not since the days of Panama Al Brown and Manuel Ortiz had a bantamweight champion looked so dominant or stood so toweringly over his peers. Eder had mastered his division with such a sublime and disciplined combination of skilful boxing and brilliantly timed power punching that old and new sages alike were hailing him as a Sugar Ray Robinson in miniature. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 6 – No 4 18Th July , 2010

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 6 – No 4 18th July , 2010 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] A Story Of Three Friends Nel Tarleton – Dick Burke – Dom Volante 2 NelTarleton Name: Nel Tarleton Alias: Nelson/Nella Birth Name: Nelson Tarleton Born: 1906-01-14 Birthplace: Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom Died: 1956-01-12 (Age:49) Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: click Born in Merseyside, Liverpool on the 14th of January 1906 as Nelson Tarleton, later adopting the name young Nel Tarleton, and known as “Nella” to his adoring Liverpool fans. Nel wasn’t an ordinary fighter, he was tall but very thin, gangly, overall Nel had never weighed over ten stone in his entire career, this was mainly due to only having only one sound lung since the age of 2 when he contracted TB. He was a keen footballer and in his early childhood he used to play out on the tough Merseyside streets just like every other young boy but he soon realised he was not strong enough to compete with the other lads, he was pushed and shoved and lacked obvious strength. He was teased about his weight and his looks only for a school bully to invite him down to the Everton Red Triangle Boxing club. It was there, and at the Gordon Institute, he learned to love the sport of boxing and was picking up prizes as early as twelve years old. -

9780816063840.Pdf

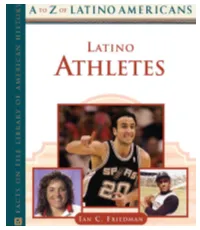

A to Z of Latino Americans Latino Athletes Ian C. Friedman For my brothers Al, Jeff, and Keith Friedman whose excitement upon hearing Al Kaline get his 3,000th hit sparked a lifetime love of sports in me ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ Latino Athletes Copyright © 2007 by Ian C. Friedman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Friedman, Ian C. Latino athletes / Ian C. Friedman. p. cm.—(A to Z of Latino Americans) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8160-6384-0 (alk. paper) 1. Hispanic American athletes—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. GV697.A1F696 2007 796.092'368073—dc22 [B] 2006016901 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Annie O’Donnell Cover design by Salvatore Luongo Printed in the United States of America VB CGI 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ List of Entries iv Acknowledgments vi Author’s Note vii Introduction viii A-to-Z Entries 1 Bibliography 253 Entries by Sport 255 Entries by Year of Birth 257 Entries by Ethnicity or Country of Origin 259 Index 261 List of Entries ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ Alomar, Roberto Clemente, Roberto Gómez, Wilfredo Alou, Felipe Concepción, Davey Gonzales, Pancho Aparicio, Luis Cordero, Angel, Jr. -

Text of Diss

For Blood or for Glory: A History of Cuban Boxing, 1898-1962 by Anju Nandlal Reejhsinghani Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Anju Nandlal Reejhsinghani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: For Blood or for Glory: A History of Cuban Boxing, 1898-1962 Committee: Frank Guridy, Supervisor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, Co-Supervisor Virginia Garrard Burnett Madeline Y. Hsu Michele B. Reid To Billy Geoghegan, my cornerman Copyright by Anju Nandlal Reejhsinghani 2009 Acknowledgments This project had its origins in January 2001, when – during a two-week trip to Havana and Matanzas as part of a U.S.-Cuba writers’ conference – I was in training for a series of amateur boxing tournaments back home. Without access to a boxing gym and unwilling to subject myself to catcalls by running in the street, I chose to train by the hotel pools, where – as my fellow writers worked on their tans or cavorted in the water – I assiduously jumped rope, did sit-ups and push-ups, and shadowboxed. My regimen, all the more unusual for its having been carried out by a woman, came to the attention of a Havana sports journalist, Martín Hacthoun, and led to his invitation to profile me for some of the national newspapers. Wary of being used for propaganda of whatever sort, I nonetheless was too curious not to accept. -

Musings from My Hermitage by Larry F

Musings from my Hermitage By Larry F. Ginsberg Hermitage Wire Service archive: Pincus Silverberg January 16, 1964: Ansonia’s own Pinky Silverberg, former NBA World Flyweight Champion who was “robbed” of his title died today at age 59. Silverberg was born on April 5, 1904 and held the Flyweight Title during 1927. He had 89 Official Bouts, won 33 (7 by KO), lost 33 (1 by KO to top contender Willie LaMorte in 1926), 15 draws, 6 no decisions and 2 no contests. He was the younger brother of the Professional Featherweight Herman “Kid Silvers”. He was known for fighting the top Flyweights and Bantamweights (when he was no longer able to make weight as a Flyweight) of his era including Dark Cloud Bradley, Kid Chocolate, Panama Al Brown and Midget Wolgast. He was survived by his wife and two children. October 17, 1925: Pinky Silverberg crowned Connecticut Flyweight Champion. Outpoints the current champ Al Beuregard in 10 rounds at the Opera House in Ansonia, CT. January 27, 1926: In a controversial decision Connecticut Flyweight Champion Pinky Silverberg was outpointed in eight rounds by top Negro Flyweight contender Ruby “Dark Cloud” Bradley at Foot Guard Hall in Hartford, CT. Hartford Current Boxing columnist questions decision. “Silverberg outsmarted Bradley, he carried the fight to Bradley and his punches were straighter and truer, he looked good to everybody except the third man in the Ring (referee).” April 5, 1926: Connecticut Flyweight Champion Pinky Silverberg TKO’d by Willie LaMorte in Third Round at the Foot Guard Hall in Hartford, CT. January 19, 1927: In a bout to benefit the great Negro Boxer Sam Langford, now totally blind, Cuban Boxer Black Bill (Eladio Valdes) outpointed Pinky Silverberg in six rounds at the Walker Athletic Club in New York. -

Boxing a Cultural History

A CULTURAL HISTORY KASIA BODDY 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 1 BOXING 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 2 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 3 BOXING A CULTURAL HISTORY KASIA BODDY reaktion books 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 4 For David Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2008 Copyright © Kasia Boddy 2008 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in China British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boddy, Kasia Boxing : a cultural history 1. Boxing – Social aspects – History 2. Boxing – History I. Title 796.8’3’09 isbn 978 1 86189 369 7 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 5 Contents Introduction 7 1 The Classical Golden Age 9 2 The English Golden Age 26 3 Pugilism and Style 55 4 ‘Fighting, Rightly Understood’ 76 5 ‘Like Any Other Profession’ 110 6 Fresh Hopes 166 7 Sport of the Future 209 8 Save Me, Jack Dempsey; Save Me, Joe Louis 257 9 King of the Hill, and Further Raging Bulls 316 Conclusion 367 References 392 Select Bibliography 456 Acknowledgements 470 Photo Acknowledgements 471 Index 472 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 6 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 7 Introduction The symbolism of boxing does not allow for ambiguity; it is, as amateur mid- dleweight Albert Camus put it, ‘utterly Manichean’. -

Migrants, Sport, and Belonging in the Interwar Greater Caribbean

The Panama Cannonballs Transnational Ties: Migrants, Sport, and Belonging in the Interwar Greater Caribbean Lara PutnaiT Department o f History University o f Pittsburgh The interwar years saw the creation o f a circum-Caribbean migratory sphere, linking British colonial sending societies like Jamaica and Barbados to receiving societies from Panama to Cuba to the Dominican Republic to the United States. The overlapping circulation o f migrants and media created transnational social fields within which sport practice and sport fandom helped build face-to-face and imagined communities alike. For the several hundred thousand British Caribbean emigrants and their children who by the late 1920s resided abroad, cricket and boxing were especially central. The study o f sport among interwar British Caribbean migrants reveals overlapping transnational ties that created microcultures o f sporting excellence. In this mobile and interconnected world, sport became a critical realm far the expression o f nested loyalties to parish, to class, to island, to empire, and to the collective they called “Our People, "that is, “the Negro Race, ” worldwide. fThe author is grateful to Rob Ruck, Theresa Runstedtler, and three anonymous reviewers for the Journal o f Sport History for very helpful comments on earlier versions. Correspondence to [email protected]. T h e Panama Am erican' s “W e s t Indian page” in August of 1926 traced a world of sports in motion. There was a challenge from the local “Wonderers CC to the Pickwick CC”— cricket clubs, of course— promising -

Ismael Laguna

Ismael Laguna ( Class of 2001 Modern Category Hall of Fame bio:click World Boxing Hall of Fame Inductee Name: Ismael Laguna Alias: El Tigre Colonense Birth Name: Ismael Laguna Meneses Born: 1943-06-28 Hometown: Colon City, Panama Birthplace: Colon City, Panama Stance: Orthodox Height: 175cm Reach: 173cm Pro Boxer: Record Promoter: Record Manager: Hector Valdez Trainer: Curro Dosman Photo #2 Biography Ismael Laguna, one of a family of nine, was born in a fishing village called Santa Isabel, near Colon, Panama on 28 June 1943. Colon was a busy port at the Caribbean end of the Panama Canal. Like many others from poor backgrounds, Laguna scraped a living as a boy by shining shoes and selling newspapers. He soon learned to fight for his pitch, and then turned to boxing at the age 12 or 13 when he found the National Champion, Carlos Watson, offering to spar with anyone on the beach. Laguna volunteered and opened a cut which was still healing from Watson's last fight. Afterwards, Watson's trainer, Chino Amon, asked the youngster if he would like to learn the art properly. Amon talked to Laguna's parents and persuaded them that it was better for their son to spend his time in a boxing gym than on the streets. Laguna fought just half a dozen times as an amateur before turning professional under manager Isaac Kretch at the age of 17. In his debut, he scored a second round knockout of Al Morgan in Colon in January 1961. Later that month, he outpointed Eduardo Frutos for his second pro fight. -

IMMAA01/// %.‘",„Wpaimmallaa440e/ 0000 I BRO ;IWO

\\%%1ALMAIMMAA01/// %.‘",„wpaimmallAA440e/ 0000 I BRO ;IWO //604-10-Wiwtirmutwmi*AW. ///e0WWWWWUVAA ■ \\ International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y. 13780 Newsletter if8 September, 1983 WELCOME IBRO welcomes new members Tracy Collis, Karel DeVries, Tom Leonard and Carl Schnipper. Their addresses and description of their boxing interests appear elsewhere in this newsletter. NEW ADDRESS Reg Noble has become our first Texas member. His address is now: P.C. Box 3666, Conroe, Texas 77305. DID YOU KNOW That Primo Carnera, in his 6th year of professional boxing, was 6 inches taller, a 6-5 favorite at &o'clock, and 60 pounds heavier than Jack Sharkey. Carnera scored his 60th career knockout in the 6th round of the 6th bout of the evening in the 6th month of 1933 when he won the heavyweight title from Sharkey. (contributed by Julius Weiner) IBRO MEETING Plans are being made for a meeting of IBRO members. Included on the agenda would be a discussion of goals and direction for the organization and possible joint projects. It is tentatively being scheduled for April, 1984 at an Eastern location. Let's hear your thoughts on this. BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY Several IBRO members are now working on biographical essays for the Biographical Dictionary of American Sport. This four-volume work is scheduled for publication by the Greenwood Press in 1986. Prof. David L. Porter, William Penn College, Cskaloosa, Iowa 52577 is the editor. He still needs authors for essays on Paul Berlenbach, Tony Canzoneri, Dixie Kid, Johnny Dundee, Billy Papke, Willie Pep, Tommy Ryan, John Henry Lewis, and Sammy Mandell. -

International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y

•■■• \\%W International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y. 13780 Newsletter #23 Volume IV, No. 5 April, 1986 CONTENTS IBRO News Other Items Membership Directory Update 194 More, about Leadville 199 JAB 196 Freddie for Eddie?) Steele 200 Information Wanted 197 Notes on Gene Tunney 205 On Request Material 198 Namesakes 206 Sports Heritage 198 Trivia Bits 206 Columns Book Reviews Boxing Rambler 204 Guinness Boxing: The Records..203 Celebrity Boxers 206 La 'Bibbia' del Pugilato '>07. Bareknuckle Notes 207 Laurence Fielding 219 Articles Records Suggestions for Improving Boxing.200 Notes, Corrections, Additions 214 Gladiators of the Prize Ring - Panama Al Brown Patsy Kerrigan 211 Johnny Fitzpatrick 226 Pat Killen 212 George Gilbody...(amateur) 228 Joe Lannon 21.3 Del Hanlon 231 Johnny Hanschen Frankie Sagilio 234 Nick Testo 235 Jabez White 278 THANKS To the following individuals for their contributions to this newsletter: Harvey Aronson, Dott. Giuseppe Ballarati, Jay Bashuk, George Blair, Dave Bloch, Tom Crome, Laurence Fielding, Michel Gladu, Bruce Harris, Peter Hatton, Tim Leone, Ian Morrison, Johnny Shevalla, Bob Soderman, Paul Stevenson, Bert Sugar, Tan Wee Eng, Julius Weiner, Dave Wolf, Paul Zabala and a special thanks to Luckett Davis. WELCOME To new members: Billy Abel, Philadelphia, PA; Bill Beaulieu, Manchester, NH; Oddbjorn Gjeilo, Oslo, Norway; John Hughes, North Cape May, NJ; Thomas McElligott, Sidney, NY; Arn Schuck, Merewether, Australia; Jack Stitt, Sydney, Australia; Ture Widlund, Stockholm, Sweden; and Young Zanetsky, Bronx, NY 1 94 MEMEBEIRIAIP• DIIREICTIDIFne UPDATE NEW MEMBERS Billy Abel 15th Round Bar 430 Belgrade St. Philadelphia, PA 19125 questionnaire not yet received Bill Beaulieu 18 Whitehall Terrace Manchester, NH 03106 Mr. -

Settling the Score the Rivalry Between Panama Al Brown and Pete Sanstol (Part II of II) by Ric Kilmer

Settling the Score The Rivalry Between Panama Al Brown and Pete Sanstol (Part II of II) by Ric Kilmer the French boxing arly 1933 was a authorities of his particularly depressing "imaginary illness," Etime for both "Panama" and that he knew Al Brown and Pete Brown was in fact Sanstol—rival bantamweight in excellent health. boxers. Lumiansky then Brown, World Champion, threatened to have had not been getting along Brown suspended in with his manager, Dave Europe, the USA, Lumiansky. Their relationship and in Great Britain. had become extremely hostile. "I won’t box!" Brown was so depressed that replied Brown. he didn’t want to fight anyone, any more, and was "You’ll box or you won’t put your gloves on for at openly defying Lumiansky. His manager had to cancel least a year. I hope whoever paid you not to box paid scheduled bouts in the United States because Brown you enough to live on for a year," his manager replied refused to leave France. Lumiansky advised Brown that in return. they had contracted to fight Henri Poutrain February 9 Lumiansky then tried to convince the press that a in Paris, but Brown was balking at that bout, too. mysterious person had hatched a plot to get rid of him. Journalists advised Lumiansky by telegram that Meanwhile, the managerial contract between Brown Brown had "declared war" with his long-time and Lumiansky—who had been together since the late American manager. Lumiansky, who was in the U.S. at 1920s—was due to expire any day now, although even the time, replied that he was surprised by the Panama Al Brown himself was unaware of the exact telegram’s contents and unaware what could have come date.