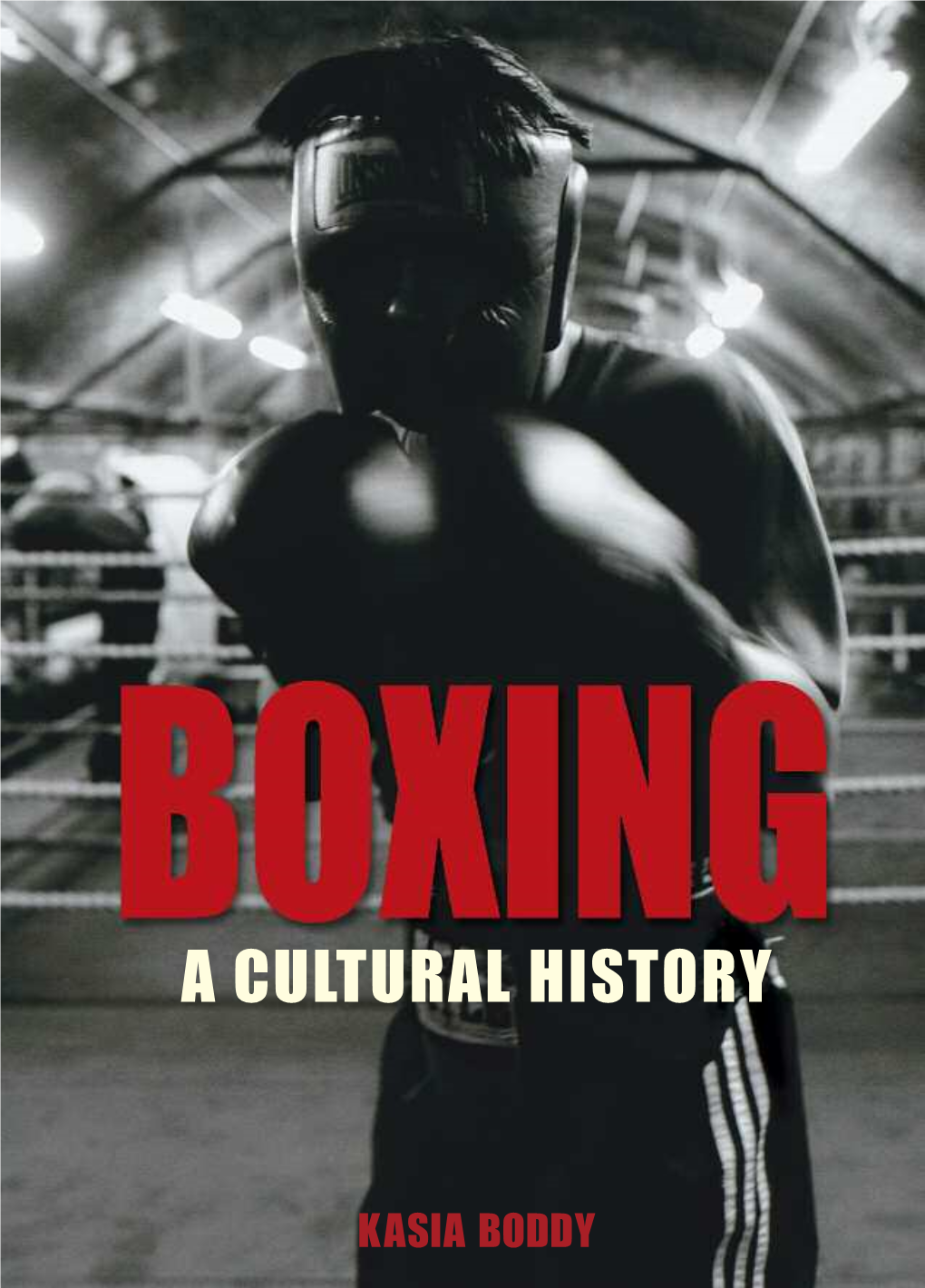

Boxing a Cultural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxing Practitioners Physiology Review 1. Kinanthropometric Parameters, Skeletal Muscle Recruitment and Ergometry

Open Journal of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, 2020, 10, 1-24 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ojmip ISSN Online: 2162-2167 ISSN Print: 2162-2159 Boxing Practitioners Physiology Review 1. Kinanthropometric Parameters, Skeletal Muscle Recruitment and Ergometry André Mukala Nsengu Tshibangu Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo How to cite this paper: Tshibangu, A.M.N. Abstract (2020) Boxing Practitioners Physiology Re- view 1. Kinanthropometric Parameters, Ske- Seven percent voluntary body weight decrease by boxers requires 21 days letal Muscle Recruitment and Ergometry. while 4.4 percent increase needs only one day. Energy and fluid intakes reduc- Open Journal of Molecular and Integrative tion does not affect boxers punching force. Boxers effective punch masses and Physiology, 10, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmip.2020.101001 body weights correlate. Wrist girths and competition rankings of boxers cor- relate. Boxers show leanness body fat percentage. Boxers, generally highly me- Received: November 16, 2019 somorphic, with increasing body weight, show ectomorphy decreases but en- Accepted: January 13, 2020 domorphy and mesomorphy increases. Vibration treatment enhances power Published: January 16, 2020 in boxers arm flexors. Presence, nature and thickness of bandages and gloves Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and donned influence boxers punch force. Stance posture adopted by boxers ends Scientific Research Publishing Inc. in locomotion functional parameters adaptations. Muscular recruitment se- This work is licensed under the Creative quence during rear straight punches may be influenced by the target height Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). (head or body levels) and the boxer intention (produce maximal force or maxim- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ al speed). -

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

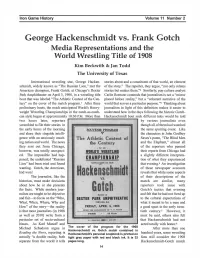

George Hackenschmidt Vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd the University of Texas

Iron Game History Volume 11 Number 2 George Hackenschmidt vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd The University of Texas International wrestling star, George Hacken- stories about and a constituent of that world, an element schmidt, widely known as "The Russian Lion," met the of the story." The reporter, they argue, "not only relates American champion, Frank Gotch, at Chicago's Dexter stories but makes them."2 Similarly, pop culture analyst Park Amphitheater on April 3, 1908, in a wrestling title Carlin Romano contends that journalism is not a "minor bout that was labeled "The Athletic Contest of the Cen- placed before reality," but a "coherent nanative of the tmy" on the cover of the match program.' After three world that serves a particular purpose."3 Thinking about preliminary bouts, the much anticipated World's Heavy- journalism in light of this definition makes it easier to weight Wrestling Championships in the catch-as-catch- understand how in the days following the historic Gotch can style began at approximately 10:30 P.M. More than Hackenschmidt bout such different tales would be told two hours later, reporters ...-------------------. by various journalists even scrambled to file their stories in though all of them had watched the early hours of the morning SOUVENIR PROGRAM the same spmting event. Like and share their ringside intelli- 'f the characters in John Godfrey gence with an anxiously await- The Athletic Contest of Saxes's poem, "The Blind Men ing nation and world. The news the Century and the Elephant," almost all they sent out from Chicago, _ For •h• _ of the reporters who pe1111ed however, was totally unexpect- WORLD'S WRESTLING their reports from Chicago had ed. -

STARS RETURN to FOUR CITIES ONLY T to WIN PENNANTS

100S. Idea that Papke Is a snap this time, and he thinks he has a good chance to STARS RETURN TO i PENNANT-WTNNFR- BASEBALL LEAGUE FOUR CITIES ONLY win back the championship. VANCOUVER. B. 0.. S OF NOT?THWF.STF.RN San Francisco sportdom is Interested In the benefits that are being arranged for the mother and sister for the late I "Bob" Smyth, who died a week ago. WAS H N GTO N TEAM FOR COAST LEAGUE Smyth was for many years sporting editor of the Call and one of the best-know- n and best-like- d men in the busi- ness. He was sick for some nine weeks before his death and aa he had not i been well for two years previous, left - little or nothing for his immediate - t Bantz, Babcock and Jarvis Rumored Agreement With the family, who were dependent on him. f The sporting world showed Its gener- v - Raise Hope of Champion- Circuit Fixes Next ous spirit by Jumping to the front. A State theatrical benefit will be given Octo- u ship at Seattle. ber 22 and will be followed by a box- J Year's Circuit. ing show on October 27. Benny Sells, manager of Joe Gans. was named as V the head of a finance committee and has already received in ' subscriptions $1010. It is fully expected that at least STRONG WHITW0RTH TEAM $6000 will be raised and handed over - i LOS ANGELES WILL HOWL tp the family. vt r LS9 Favorable Keports Come From According to Report. Coasters Have Pullman and Moscow, While Ore-eo- n Had Enough War and AVill and Corvallls Are Rounding; Withdraw From frjira-meiit- o IXTERSCHOIASTIC TEAMS PITT Into Form. -

My Fighting Life

MY MY FIGHTING LIFE Photo: Hana Studios, Ltd. _/^ My Fighting Life BY GEORGES GARPENTIER (Champion Heavy-wight Boxer of With Eleven Illustrations CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1920 To All British Sportsmen I dedicate this, The Story of My Life. Were I of their own great country, I feel I could have no surer, no warmer, no more lasting place in their friendship CONTENTS CHAPTBX FAGB 1. I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL ... 1 2. To PARIS 21 3. MY PROFESSIONAL CAREER BEGINS . 30 4. I Box IN ENGLAND ..... 47 5. MY FIGHTS WITH LEDOUX, LEWIS, SULLIVAN AND OTHERS ..... 51 6. I MEET THE ILLINOIS THUNDERBOLT . 68 7. MY FIGHTS WITH WELLS AND A SEQUEL . 79 8. FIGHTS IN 1914 99 9. THE GREAT WAR : I BECOME A FLYING MAN 118 10. MILITARY BOXING ..... 133 11. ARRANGING THE BECKETT FIGHT . 141 12. THE GREAT FIGHT 150 13. PSYCHOLOGY AND BOXING . 158 14. How I TRAINED TO MEET BECKETT . 170 15. THE FUTURE OF BOXING : TRAINING HINTS AND SECRETS . .191 16. A CHAPTER ON FRA^OIS DESCAMPS . 199 17. MEN I HAVE FOUGHT .... 225 ILLUSTRATIONS GEORGES CARPENTIER .... Frontispiece FACING PAGE 1. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF TWELVE . 10 CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF THIRTEEN . 10 2. CARPENTIER (WHEN ELEVEN) WITH DESCAMPS . 24 CARPENTIER AND LEDOUX . .24 3. M. DESCAMPS ...... 66 4. CARPENTIER WHEN AN AIRMAN . .180 5. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTEEN . 168 CARPENTIER TO-DAY . .. .168 6. CARPENTIER IN FIGHTING TRIM . 226 7. M. AND Mme. GEORGES CARPENTIER . 248 MY FIGHTING LIFE CHAPTER I I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL OUTSIDE my home in Paris many thousands of my countrymen shouted and roared and screamed; women tossed nosegays and blew kisses up to my windows. -

North East History 39 2008 History Volume 39 2008

north east history north north east history volume 39 east biography and appreciation North East History 39 2008 history Volume 39 2008 Doug Malloch Don Edwards 1918-2008 1912-2005 John Toft René & Sid Chaplin Special Theme: Slavery, abolition & north east England This is the logo from our web site at:www.nelh.net. Visit it for news of activities. You will find an index of all volumes 1819: Newcastle Town Moor Reform Demonstration back to 1968. Chartism:Repression or restraint 19th Century Vaccination controversies plus oral history and reviews Volume 39 north east labour history society 2008 journal of the north east labour history society north east history north east history Volume 39 2008 ISSN 14743248 NORTHUMBERLAND © 2008 Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate TYNE & Pegswood WEAR Morpeth Northumberland NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Editorial Collective: Willie Thompson (Editor) John Charlton, John Creaby, Sandy Irvine, Lewis Mates, Marie-Thérèse Mayne, Paul Mayne, Matt Perry, Ben Sellers, Win Stokes (Reviews Editor) and Don Watson . journal of the north east labour history society www.nelh.net north east history Contents Editorial 5 Notes on Contributors 7 Acknowledgements and Permissions 8 Articles and Essays 9 Special Theme – Slavery, Abolition and North East England Introduction John Charlton 9 Black People and the North East Sean Creighton 11 America, Slavery and North East Quakers Patricia Hix 25 The Republic of Letters Peter Livsey 45 A Northumbrian Family in Jamaica - The Hendersons of Felton Valerie Glass 54 Sunderland and Abolition Tamsin Lilley 67 Articles 1819:Waterloo, Peterloo and Newcastle Town Moor John Charlton 79 Chartism – Repression of Restraint? Ben Nixon 109 Smallpox Vaccination Controversy Candice Brockwell 121 The Society’s Fortieth Anniversary Stuart Howard 137 People's Theatre: People's Education Keith Armstrong 144 2 north east history Recollections John Toft interview with John Creaby 153 Douglas Malloch interview with John Charlton 179 Educating René pt. -

The Royal Australian Navy Historic Flight

The Quarterly Journal of the Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia Inc. Volume12 Number2 April2001 I:--. lt) O') ....... e"' cl -0 ~ i "1::l ~-~"' :0 Cl ~ CJ ~ ~ Cl) 805 SQUADRON RE-COMMISSIONED 28 FEBRUARY2001 With Kaman 'Super Sea Sprite' helicopters 'We wish them all the very best' Photo courtesy BANAS Photographic Section Publishedby the FleetAir ArmAssociation of Australia Inc PrintPost Approved -PP201494/00022 Editor:John Arnold -PO Box662 , NOWRANSW 2541 , Australia. Phone/Fax(02) 4423 2412 -Mobile 0402 264 494 - [email protected] ::r SHELF ro1so.111 CW2-C Slipstream ~ -------------- FOREWORD by CAPTAINTW BARRETT As the incoming Commanding Officer at HMAS ALBATROSS, I thank you for the opportunity to contribute to Slipstream. I note, with considerable satisfaction, the detail presented by the Chief of the Defence Force, Chief of Navy, Maritime Commander and Commander, Australian Naval Aviation Group in previous editions of Slipstream. The picture they were able to present demonstrates the significant enhancements currently being made to the Fleet Air Arm - in terms of equipment and facilities. We are indeed fortunate to have such an expansion of capabilities in /" 0 "" I C2I a time of relative constraint elsewhere in Defence. I would like to focus my comments on the personnel aspects of this expansion , for without the right people, new equipment and facilities are useless . I have to say we are being challenged at the moment to find and retain people for our demanding profession. This is a reflection of the changes in our society. At a recent conference I heard the Warrant Officer of the Navy describe the contemporary sailor. -

Jackie Brown (Manchester)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Jackie Brown (Manchester) Active: 1925-1939 Weight classes fought in: fly, bantam Recorded fights: 138 contests (won: 105 lost: 24 drew: 9) Born: 29th November 1909 Died: 5th March 1971 Manager: Harry Fleming Fight Record 1925 May 18 Harry Gainey (Gorton) WPTS(6) Arena, Collyhurst Source: Harold Alderman (Boxing Historian) 1926 Mar 23 Dick Manning (Manchester) WPTS(6) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 31/03/1926 page 126 1927 Mar 5 Tommy Brown (Salford) LPTS(10) Sussex Street Club, Salford Source: Boxing 09/03/1927 page 44 Mar 8 Billy Cahill (Openshaw) WKO6 Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Promoter: Jack Smith Mar 15 Freddie Webb (Salford) LRSF3(3) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 23/03/1927 page 75 (7st 10lbs competition) Promoter: Jack Smith May 15 Ernie Hendricks (Salford) DRAW(10) Adelphi Club, Salford Source: Boxing 18/05/1927 page 218 Jul 7 Young Fagill (Liverpool) WDSQ1(6) Pudsey Street Stadium, Liverpool Source: Boxing 12/07/1927 page 401 Match made at 8st 4lbs Referee: WJ Farnell Sep 27 Joe Fleming (Rochdale) WPTS(6) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 04/10/1927 page 152 Promoter: Jack Smith Oct 7 Harry Yates (Ashton) WPTS(10) Ashbury Hall, Openshaw Source: Boxing 11/10/1927 page 173 Nov 4 Freddie Webb (Salford) WPTS(10) Ashbury Hall, Openshaw Source: Boxing 08/11/1927 page 235 Nov 18 Jack Cantwell (Gilfach Goch) -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Npc Bodybuilding Division Rules

NATIONAL PHYSIQUE COMMITTEE OF THE USA PO Box 3711, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15230 USA TOLL FREE: 1-866-304-4322 PHONE: 412-276-5027 FAX: 412-281-0471 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.NPCnewsOnline.com NPC BODYBUILDING DIVISION RULES Posing Music • Posing Music will be used at the Finals only. • Posing Music must be on CD and must be the only music on the CD. • Posing Music should be cued to the start of the music. N • Posing Music must not contain vulgar lyrics. Competitors Membership using music containing vulgar lyrics will be disqualifi ed. Each competitor must be a member of the NPC. Onstage Complete Registration Card • During the Prejudging male and female competitors are not on the back of this Issue. permitted to wear any jewelry onstage other than a wedding band. Decorative pieces in the hair are not permitted. • During the Finals female competitors are permitted to wear earrings. Competitor Rules • No glasses, props or gum are permitted onstage. • Any competitor doing the “Moon Pose” will be disqualifi ed. Check-Ins • Lying on the fl oor is prohibited. Competitors will be checked in and weighed. • Bumping and shoving is prohibited. First and second persons involved will be disqualifi ed. Posing Suits • Competitors numbers will be worn on the left side of the suit • All suit bottoms must be V-shaped, no thongs are permitted. bottom during both Prejudging and Finals. • Suits worn by male competitors at the prejudging and fi nals must be plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle Backstage or fl uorescents. The only people permitted in the backstage area are: • Suits worn by female competitors at the Prejudging must be • Competitors two-piece and plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle • Expediters or fl uorescents. -

Faust Und Geist. Literatur Und Boxen Zwischen Den Weltkriegen

Wolfgang Paterno FAUST UND GEIST Literatur und Boxen zwischen den Weltkriegen 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund ( FWF ): PUB 458-G30 Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0; siehe http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Duell zwischen Jack Dempsey und Georges Carpentier in der Arena Boyle’s Thirty Acres, Jersey City, New Jersey, 2. Juli 192. (© Illustrated London News Ltd / Mary Evans / picturedesk.com) © 2018 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Lektorat: Katharina Krones, Wien Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz und Layout: Bettina Waringer, Wien Druck und Bindung: Hubert & Co GmbH & Co.KG, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, D-37079 Göttingen Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in the EU ISBN 978-3-205-20545-6 In Erinnerung an den alten Boxer Quido Paterno (1937–2016) Inhalt EINLEITUNG 9 ..................................... TEILI.ZEITZEICHENBOXEN Grundlagen..................................... 15 Kritikpunkte: Propagierungsmaschinerie .................... 21 Fokussierung: Recherchewege und Kapitelüberblick .............. 29 Vorstellung -

Get Ebook > in the Ring with Bob Fitzsimmons (Hardback)

UQ6NWQHYHGKN » Doc » In the Ring With Bob Fitzsimmons (Hardback) Download Book IN THE RING WITH BOB FITZSIMMONS (HARDBACK) Adam J Pollack, United States, 2007. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. This is the third book in Adam Pollack s series on the heavyweight champions of the gloved era. Bob Fitzsimmons was boxing s rst pound for pound great, winning the world middleweight title before becoming the world heavyweight champion (and later lightheavyweight champ). Combining both crafty skill and crushing power, Fitzsimmons was able to knock out heavyweights when he only... Read PDF In the Ring With Bob Fitzsimmons (Hardback) Authored by Adam J. Pollack Released at 2007 Filesize: 1.8 MB Reviews Denitely among the nest pdf I actually have at any time read through. It is one of the most amazing pdf i actually have study. I discovered this ebook from my i and dad recommended this pdf to find out. -- Turner Stiedemann Thorough guide! Its this kind of excellent go through. It normally will not price an excessive amount of. You may like just how the blogger compose this ebook. -- Mrs. Linnea McKenzie TERMS | DMCA RXRXVPXW3KOE » Kindle » In the Ring With Bob Fitzsimmons (Hardback) Related Books The Kid Friendly ADHD and Autism Cookbook The Ultimate Guide to the Gluten Free Casein Free Diet by Pamela J Compart and Dana Laake 2006... Fart Book African Bean Fart Adventures in the Jungle: Short Stories with Moral California Version of Who Am I in the Lives of Children? an Introduction to Early Childhood Education, Enhanced Pearson Etext with Loose-Leaf Version -- Access..