Genius with the Samba Beat: Golden Bantam Eder Jofre Was the Complete Fighter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wbc´S Lightweight World Champions

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC FLYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT ARIAKE COLOSSEUM / TOKYO, JAPAN MARCH 20, 2017 THIS WILL BE WBC’S 1, 968 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN THE 54 YEARS HISTORY OF THE WBC AKIHIKO HONDA & TEIKEN BOXING PROMOTIONS, PRESENTS: JUAN HERNANDEZ DAIGO HIGA (MEXICO) (JAPAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC OFFICIAL CHALLENGER DATE OF BIRTH: FEBRUARY 24, 1987 DATE OF BIRTH: AUGUST 9, 1995 PLACE OF BIRTH: COAHUITLAN, VERACRUZ PLACE OF BIRTH: URASOE, JAPAN AGE: 30 AGE: 21 RESIDES: MEXICO CITY RESIDES: TOKYO, JAPAN ALIAS: CHURRITOS ALIAS: PROF. RECORD: 34-2-0, 25 KO’S PROF. RECORD: 12-0-0, 12 KO’S GUARD: ORTHODOX GUARD: ORTHODOX TOTAL ROUNDS: 144 TOTAL ROUNDS: 42 WBC TITLES FIGHTS: 2 (1-1-0) WBC TITLES: YOUTH / OPBF MANAGER: ISAAC BUSTOS MANAGER: AKIHIKO HONDA ALJ PROMOTER: PROMOCIONES DEL PUEBLO PROMOTER: TEIKEN BOXING PROMOTIONS WBC´S FLYWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. PONE KINGPETCH (THA) 1963 2. HIROYUKI EBIHARA (JAP) 1963 - 1964 3. PONE KINGPETCH (THA) * 1964 - 1965 4. SALVATORE BURRUNI (ITALY) 1965 - 1966 5. WALTER MCGOWAN (GB) 1966 6. CHARTCHAI CHIONOI (THA) 1966 - 1969 7. EFREN TORRES (MEX) 1969 - 1970 8. CHARTCHAI CHIONOI (THA) * 1970 9. ERBITO SALAVARRIA (PHIL) 1970 - 1971 10. BETULIO GONZALEZ (VEN) 1972 11. VENICE BORKORSOR (THA) 1972 - 1973 12. BETULIO GONZALEZ (VEN) * 1973 - 1974 13. SHOJI OGUMA (JAP) 1974 - 1975 14. MIGUEL CANTO (MEX) 1975 - 1979 15. CHAN-HEE PARK (KOR) 1979 - 1980 16. SHOJI OGUMA (JAPAN) * 1980 - 1981 17. ANTONIO AVELAR (MEX) 1981 - 1982 18. PRUDENCIO CARDONA (COL) 1982 19. -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Pacific Citizen) with the Enemy Act

New eligibility rules in effect for JACL keg meet PACIFIC · -:CITIZEN LOS ANGELES-Entry fOl'm ~ 1'ournament enl!'ies must be M.mbmhlP Publication: Japan". Am"ltln CIII, ..s ~'"". 125 Wtillr 51.. L.. l"'l.I ... Ca 90012 (213) MA 6·4471 (or the 21.t nnnual Nallonal certified 8S to JACL member· Publlsh.d Woolly Empt ~ ..t Wook of th. Y• ., ,- s...~ Clm P.. ",. ',Id at Los Ant.I .., Calif, IN THIS ISSUE JACL Nisei Bowling Tourna· ship and o[(leial league aver· ment arc due Monday. J"n. ages by the localochapter pres· '" CENERAL NEWS Vol. 64 No. 2 FRIDAY, JANUARY 13, 1967 Edit/Bus. Office: MA 6-6936 CaUfornl. brit't ~ 'oqutn\ In plud~ 23. tournament chairman Easy idant or member of the Na· TEN CENTS t"1 for yen claims cue before Fujimoto reminded today. tlonal JACL Advisory Board U.S, Supreme Court: L.A "0" ttN to decide on evacuee pcn· Entry fees must accompany on Bowling, $lon c~U •...••.. 1 aU entries willl checks made AU bowlers will be dlecked payabte to YD S Mlnamide. for ABC. W10C and J ACL NATIONAL~ACL '" Ty New ellclbllt~ · rules clfcell\ e for troosurer. and maUed to membership cards at time 01 1967 J ACL Nat.'1 Nisei bowlinE Kajimoto. 1246 Gardena Blvd .• registration. tournament.: Nat.'l JACL Credo· Gardena. C<lli!. 90247. Enterinr Avera,.. 1\ Union dtCl8ff.S 5 pel • 1 Calif. brief eloquent in pleading SJ'A :!O CommlHt't celtbrates vic· Entry forms lor mcn's and P articipants in each event lor~' In StaHle , ..•...... -

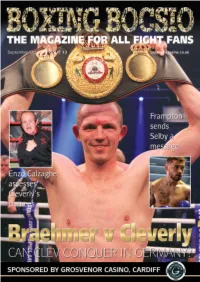

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

The Panama Cannonball's Transnational Ties: Migrants, Sport

PUTNAM: THE PANAMA CANNONBALL’S TRANSNATIONAL TIES The Panama Cannonball’s Transnational Ties: Migrants, Sport, and Belonging in the Interwar Greater Caribbean LARA PUTNAM† Department of History University of Pittsburgh The interwar years saw the creation of a circum-Caribbean migratory sphere, linking British colonial sending societies like Jamaica and Barbados to receiving societies from Panama to Cuba to the Dominican Republic to the United States. The overlapping circulation of migrants and media created transnational social fields within which sport practice and sport fandom helped build face-to-face and imagined communities alike. For the several hundred thousand British Caribbean emigrants and their children who by the late 1920s resided abroad, cricket and boxing were especially central. The study of sport among interwar British Caribbean migrants reveals overlapping transnational ties that created microcultures of sporting excellence. In this mobile and interconnected world, sport became a critical realm for the expression of nested loyalties to parish, to class, to island, to empire, and to the collective they called “Our People,” that is, “the Negro Race,” worldwide. †The author is grateful to Rob Ruck, Theresa Runstedtler, and three anonymous reviewers for the Journal of Sport History for very helpful comments on earlier versions. Correspondence to [email protected]. Fall 2014 401 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY THE PANAMA AMERICAN’S “WEST INDIAN PAGE” in August of 1926 traced a world of sports in motion. There was a challenge from -

Fight Record Howard Winstone (Merthyr)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Howard Winstone (Merthyr) Active: 1959-1968 Weight classes fought in: feather Recorded fights: 67 contests (won: 61 lost: 6) Born: 15th April 1939 Fight Record 1959 Feb 24 Billy Graydon (Bethnal Green) WPTS(6) Empire Pool, Wembley Source: Boxing News 27/02/1959 pages 4 and 5 Winstone 8st 12lbs Graydon 9st 1lbs 12ozs Mar 14 Peter Sexton (Charlton) WPTS(6) Stow Hill Drill Hall, Newport Source: Boxing News 20/03/1959 page 12 Winstone 8st 13lbs 8ozs Sexton 8st 12lbs 8ozs Attendance: 600 Apr 15 Tommy Williams (Cardiff) WPTS(6) Sophia Gardens, Cardiff Source: Boxing News 24/04/1959 page 15 Winstone 9st 2lbs 8ozs Williams 9st 0lbs 8ozs Promoter: Stan Cottle & Sid Wignall Attendance: 2000 (capacity 3000) May 27 Jackie Bowers (Canning Town) WPTS(6) Sophia Gardens, Cardiff Source: Boxing News 05/06/1959 page 12 Winstone 8st 11lbs 8ozs Bowers 9st 0lbs 8ozs Promoter: Stan Cottle Capacity house of 3000 Jun 24 Jake O'Neal (Morden) WPTS(6) Coney Beach Arena, Porthcawl Source: Boxing News 03/07/1959 page 8 Winstone 8st 11lbs O'Neal 9st 0lbs Promoter: Sir Leslie Joseph Attendance: 12000 Jul 14 Ollie Wyllie (Aberdeen) WPTS(6) Ynys Stadium, Aberdare Source: Boxing News 24/07/1959 page 7 Winstone 8st 10lbs 4ozs Wyllie 9st 2lbs Promoter: Theo Davies(Merthyr) Attendance: 5000 Aug 8 Hugh O'Neill (Walworth) WPTS(6) Welfare Ground, Ebbw Vale Source: Boxing News 14/08/1959 page 7 Winstone 8st 10lbs 12ozs O'Neill 8st 13lbs 8ozs Promoter: S A Evans Sep 1 Billy Calvert (Sheffield) WRSF7(8) Ynys Stadium, Aberdare Source: Boxing News 11/09/1959 page 4 Calvert boxed for the British Featherweight Title 1963 and was Central Area Featherweight Champion 1960. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 6 – No 4 18Th July , 2010

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 6 – No 4 18th July , 2010 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] A Story Of Three Friends Nel Tarleton – Dick Burke – Dom Volante 2 NelTarleton Name: Nel Tarleton Alias: Nelson/Nella Birth Name: Nelson Tarleton Born: 1906-01-14 Birthplace: Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom Died: 1956-01-12 (Age:49) Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: click Born in Merseyside, Liverpool on the 14th of January 1906 as Nelson Tarleton, later adopting the name young Nel Tarleton, and known as “Nella” to his adoring Liverpool fans. Nel wasn’t an ordinary fighter, he was tall but very thin, gangly, overall Nel had never weighed over ten stone in his entire career, this was mainly due to only having only one sound lung since the age of 2 when he contracted TB. He was a keen footballer and in his early childhood he used to play out on the tough Merseyside streets just like every other young boy but he soon realised he was not strong enough to compete with the other lads, he was pushed and shoved and lacked obvious strength. He was teased about his weight and his looks only for a school bully to invite him down to the Everton Red Triangle Boxing club. It was there, and at the Gordon Institute, he learned to love the sport of boxing and was picking up prizes as early as twelve years old. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

EXTRACT FROM BOOK PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Thursday, 31 October 2013 (Extract from book 14) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry (from 22 April 2013) Premier, Minister for Regional Cities and Minister for Racing .......... The Hon. D. V. Napthine, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for State Development, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development ................................ The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. M. A. O’Brien, MP Minister for Innovation, Services and Small Business, Minister for Tourism and Major Events, and Minister for Employment and Trade .. The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations ..................................................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing .......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs .... The Hon. H. F. Delahunty, MP Minister for Education ............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Planning ............................................. The Hon. M. J. Guy, MLC Minister for Higher Education and Skills, and Minister responsible for the Teaching -

![Vicente Saldívar Elgranpíumaausente;1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2546/vicente-sald%C3%ADvar-elgranp%C3%ADumaausente-1-2932546.webp)

Vicente Saldívar Elgranpíumaausente;1]

Vicente Saldívar elgranpÍumaausente;1] • ione como titular mundial’ En seguida pudimos cercioramos que Con su retirada ha provocado S AMERICANOS :-. «INVESTIGAN OTRO CAMPEON. ‘ , un verdadero alud de «titula Dos, meses después, en mar res mundiales» zo, en’ el Auditório Olimpicó de Los Angeles, y bájo la protección” de la «World Boxing Associ’ tion», se anuncié el cónibate pa Howard Winstone, Raúl Rojas se sustituir, también, a Vicente Saldivú, en el trono «vacante». Uno cree a veces qúe no hay peor y Johnny Famechon se dispu sordo que el que no quiere oir. Y por lo que se refiere a estos tan su sucesión;0] organizadores y a la W.B.A. «Ig noraban» por ‘completo que .en ma... Ya decíamos antes que Sal Moore, quien en menos de un Európa ya habia un campeón, al, divar ha sido en el peso pluma asalto Se’ sacó de encima a’ Valer. que Saldivar habia dado la• al-, uno de esos campeones que sur • yohiendo’ a’ Famechón y’ el ternativa desde su stlla de ring-. ji muy de tarde en tarde, que’,, «cempeónató mundial» versión al comprobar como habla ‘derro- ..pudo .parangonars con los mái australiana, celebrado el’ ‘pasado tado a Seki. ‘ ‘ , ‘ clásicos titulares de la divisióii mayo, en Sidney, añadiremos que En fin que el campeonato de ‘ de todos los tiempos. triunfé Johnny de Danny Valdez. Los’ Angeles lo disputaron Raul al ser éste descalifiçado, después Rojas, californiano, y Eduardo’ de cinco avisos, en’ el asalto dé Higgins, de Colombia, erigién AUSTRALIA TAMB lEN cimo tercero. Digamos enseguida dose vencedor Rojas tras quince «PROcLAMAIP: SU TI1IJLAR que Johnny Famechón no nece asaltos ‘de dura brega: sitó la ayudá del ,árbitro ‘puesto No discutimos la clase de Raul Despu& de los campeonatos que llévaba ganados ¿dho asaltos, Rojas ya que a través de su carre Winstone-Seki y Rojas-Higgins tres fueron de Valdez y uno nu ra demostró poseerla. -

Wbc Bantamweight Championship

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC SUPERFEATHERWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT FORUM / INGLEWOOD, CALIFORNIA, USA JULY 15, 2017 THIS WILL BE WBC’S 1, 973 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN THE 54 YEARS HISTORY OF THE WBC OSCAR DE LA HOYA & GOLDEN BOY PROMOTIONS PRESENT: MIGUEL BERCHELT TAKASHI MIURA (MEXICO) (JAPAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC No. 1 / OFFICIAL CHALLENGER DATE OF BIRTH: NOVEMBER 17, 1991 DATE OF BIRTH: MAY 14, 1984 BIRTH PLACE: CANCUN, Q. ROO BIRTH PLACE: YAMAMOTO, AKITA RESIDENCE: MERIDA, YUCATAN RESIDENCE: TOKYO, JAPAN AGE: 25 AGE: 33 RECORD: 31-1-0, 28 KO’S RECORD: 31-3-2, 24 KO’S KO%: 88 % KO%: 67 % ALIAS: EL ALACRAN ALIAS: GUARD: ORTHODOX GUARD: SOUTHPAW TOTAL ROUNDS: 110 TOTAL ROUNDS: 207 WORLD TITLES FIGHTS: 3 (3-0-0) WORLD TITLES FIGHTS: 6 (4-2-0) MANAGER: ALFREDO CABALLERO MANAGER: AKIHIKO HONDA PROMOTER: PROMOCIONES ZANFER PROMOTER: TEIKEN PROMOTIONS WBC´S SUPERFEATHERWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. GABRIEL ELORDE (PHIL) 1963 - 1967 2. YOSHIAKI NUMATA (JAP) 1967 3. HIROSHI KOBAYASHI (JAPAN) 1967 – 1968 4. RENE BARRIENTOS (PHIL) 1969 – 1970 5. YOSHIAKI NUMATA (JAPAN) * 1970 - 1971 6. RICARDO ARREDONDO (MEX) 1971 - 1974 7. KUNIAKI SHIBATA (JAP) 1974 - 1975 8. ALFREDO ESCALERA (P. RICO) 1975 - 1978 9. ALEXIS ARGUELLO (NIC) 1978 - 1980 10. RAFAEL LIMON (MEX) 1980 - 1981 11. CORNELIUS BOZA-EDWARDS (UGA) 1981 12. ROLANDO NAVARRETE (PHIL) 1981 - 1982 13. RAFAEL LIMON (MEX) * 1982 14. BOBBY CHACON (US) 1982 - 1983 15. HECTOR CAMACHO (P. RICO) 1983 16. JULIO CESAR CHAVEZ (MEX) 1984 - 1987 17. -

October 4, 2014 This Will Be Wbc’S 1, 869 Championship Title Fight in the 52 Years History of the Wbc Reginaldo & Osvaldo Kuchle / Promociones Del Pueblo Presents

WBC FEATHERWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT CANCHA DE USOS MULTIPLES PRADERAS DE VILLA LOS MOCHIS, SINALOA, MEXICO OCTOBER 4, 2014 THIS WILL BE WBC’S 1, 869 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN THE 52 YEARS HISTORY OF THE WBC REGINALDO & OSVALDO KUCHLE / PROMOCIONES DEL PUEBLO PRESENTS: JHONNY GONZALEZ JORGE ARCE (MEXICO) WBC CHMAPION (MEXICO) WBC CHALLENGER Nationality: Mexican Nationality: Mexico Date of Birth: September 15, 1981 Date of Birth: July 27, 1979 Birthplace: Pachuca, Hidalgo Birthplace: Los Mochis, Sinaloa Residence: Mexico City Residence: Los Mochis, Sinaloa Record: 56-8-0, 47 KO’s Record: 64-7-2, 49 KO’s Age: 33 Age: 35 Guard: Orthodox Guard: Orthodox Total rounds: 313 Total rounds: 426 Title Fights: 17 (13-4-0) Titles Fights: 25 (20-5-0) Manager: Ignacio Beristain Manager: Promoter: Promociones del Pueblo Promoter: Zanfer Promotions WBC´S FEATHERWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. DAVEY MOORE (US) + 1963 25. ALEJANDRO GONZALEZ (MEX) 1995 2. ULTIMINIO RAMOS (MEX) 1963 - 1964 26. MANUEL MEDINA (MEX) 1995 3. VICENTE SALDIVAR (MEX) + 1964 - 1967 27. LUISITO ESPINOSA (PHIL) 1995 - 1999 4. HOWARD WINSTONE (GALES) + 1968 28. CESAR SOTO (MEX) 1999 5. JOSE LEGRA (CUBA) 1968 - 1969 29. NASEEM HAMED (GB) 1999 6. JOHNNY FAMECHON (FRAN) 1969 - 1970 30. GUTY ESPADAS (MEX) 200 - 2001 7. VICENTE SALDIVAR (MEX) * + 1970 31. ERIK MORALES (MEX) 2001 - 2002 8. KUNIAKI SHIBATA (JAPAN) 1970 - 1972 32. MARCO A. BARRERA (MEX) 2002 9. CLEMENTE SANCHEZ (MEX) + 1972 33. ERIK MORALES (MEX) * 2002 - 2003 10. JOSE LEGRA (CUBA) * 1972 - 1973 34. INJIN CHI (KOREA) 2004 - 2006 11. EDER JOFRE (BRA) 1973 35. -

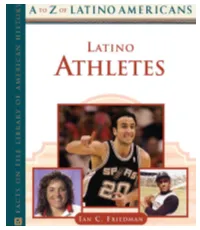

9780816063840.Pdf

A to Z of Latino Americans Latino Athletes Ian C. Friedman For my brothers Al, Jeff, and Keith Friedman whose excitement upon hearing Al Kaline get his 3,000th hit sparked a lifetime love of sports in me ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ Latino Athletes Copyright © 2007 by Ian C. Friedman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Friedman, Ian C. Latino athletes / Ian C. Friedman. p. cm.—(A to Z of Latino Americans) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8160-6384-0 (alk. paper) 1. Hispanic American athletes—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. GV697.A1F696 2007 796.092'368073—dc22 [B] 2006016901 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Annie O’Donnell Cover design by Salvatore Luongo Printed in the United States of America VB CGI 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ List of Entries iv Acknowledgments vi Author’s Note vii Introduction viii A-to-Z Entries 1 Bibliography 253 Entries by Sport 255 Entries by Year of Birth 257 Entries by Ethnicity or Country of Origin 259 Index 261 List of Entries ĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎĎ Alomar, Roberto Clemente, Roberto Gómez, Wilfredo Alou, Felipe Concepción, Davey Gonzales, Pancho Aparicio, Luis Cordero, Angel, Jr.